Prescrire's Contribution to the WHO Consultation on List 105 Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Predictive QSAR Tools to Aid in Early Process Development of Monoclonal Antibodies

Predictive QSAR tools to aid in early process development of monoclonal antibodies John Micael Andreas Karlberg Published work submitted to Newcastle University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the School of Engineering November 2019 Abstract Monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) have become one of the fastest growing markets for diagnostic and therapeutic treatments over the last 30 years with a global sales revenue around $89 billion reported in 2017. A popular framework widely used in pharmaceutical industries for designing manufacturing processes for mAbs is Quality by Design (QbD) due to providing a structured and systematic approach in investigation and screening process parameters that might influence the product quality. However, due to the large number of product quality attributes (CQAs) and process parameters that exist in an mAb process platform, extensive investigation is needed to characterise their impact on the product quality which makes the process development costly and time consuming. There is thus an urgent need for methods and tools that can be used for early risk-based selection of critical product properties and process factors to reduce the number of potential factors that have to be investigated, thereby aiding in speeding up the process development and reduce costs. In this study, a framework for predictive model development based on Quantitative Structure- Activity Relationship (QSAR) modelling was developed to link structural features and properties of mAbs to Hydrophobic Interaction Chromatography (HIC) retention times and expressed mAb yield from HEK cells. Model development was based on a structured approach for incremental model refinement and evaluation that aided in increasing model performance until becoming acceptable in accordance to the OECD guidelines for QSAR models. -

Classification Decisions Taken by the Harmonized System Committee from the 47Th to 60Th Sessions (2011

CLASSIFICATION DECISIONS TAKEN BY THE HARMONIZED SYSTEM COMMITTEE FROM THE 47TH TO 60TH SESSIONS (2011 - 2018) WORLD CUSTOMS ORGANIZATION Rue du Marché 30 B-1210 Brussels Belgium November 2011 Copyright © 2011 World Customs Organization. All rights reserved. Requests and inquiries concerning translation, reproduction and adaptation rights should be addressed to [email protected]. D/2011/0448/25 The following list contains the classification decisions (other than those subject to a reservation) taken by the Harmonized System Committee ( 47th Session – March 2011) on specific products, together with their related Harmonized System code numbers and, in certain cases, the classification rationale. Advice Parties seeking to import or export merchandise covered by a decision are advised to verify the implementation of the decision by the importing or exporting country, as the case may be. HS codes Classification No Product description Classification considered rationale 1. Preparation, in the form of a powder, consisting of 92 % sugar, 6 % 2106.90 GRIs 1 and 6 black currant powder, anticaking agent, citric acid and black currant flavouring, put up for retail sale in 32-gram sachets, intended to be consumed as a beverage after mixing with hot water. 2. Vanutide cridificar (INN List 100). 3002.20 3. Certain INN products. Chapters 28, 29 (See “INN List 101” at the end of this publication.) and 30 4. Certain INN products. Chapters 13, 29 (See “INN List 102” at the end of this publication.) and 30 5. Certain INN products. Chapters 28, 29, (See “INN List 103” at the end of this publication.) 30, 35 and 39 6. Re-classification of INN products. -

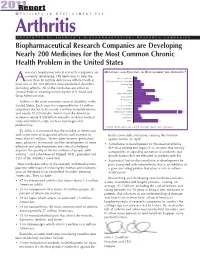

Report, Please Call the Telephone Number Listed

201R1e port M E D I C I N E S I N D E V E L O P M E N T F O R Arthritis P R E S E N T E D B Y A M E R I C A ’ S B I O P H A R M A C E U T I C A L R E S E A R C H C O M P A N I E S Biopharmaceutical Research Companies are Developing Nearly 200 Medicines for the Most Common Chronic Health Problem in the United States merica’s biopharmaceutical research companies are MEDICINES AND VACCINES IN DEVELOPMENT FOR ARTHRITIS* currently developing 198 medicines to help the Behcet’s Syndrome 3 more than 50 million Americans afflicted with at A Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy 6 least one of the 100 different musculoskeletal disorders, Fibromyalgia 9 including arthritis. All of the medicines are either in Gout 7 clinical trials or awaiting review by the U.S. Food and Lupus 19 Muscle Disorders 11 Drug Administration. Osteoarthritis 19 Osteoporosis 23 Arthritis is the most common cause of disability in the Pain 15 United States. Each year, it is responsible for 44 million Psoriatic Arthritis 7 outpatient doctor visits, nearly 1 million hospitalizations, Raynaud’s Disease 4 and nearly 10,000 deaths. And it costs the American Rheumatoid Arthritis 67 Scleroderma 6 economy nearly $128 billion annually in direct medical Spondylitis 7 costs and indirect costs, such as lost wages and Other 22 productivity. * Some medicines are listed in more than one category. -

Looking for Therapeutic Antibodies in Next Generation Sequencing Repositories

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/572958; this version posted March 10, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY 4.0 International license. Title: Looking for Therapeutic Antibodies in Next Generation Sequencing Repositories. Authors: Konrad Krawczyk1*, Matthew Raybould2, Aleksandr Kovaltsuk2, Charlotte M. Deane2 1 NaturalAntibody, Hamburg, Germany 2 Oxford University Department of Statistics, Oxford, UK *Correspondence to [email protected] Abstract: Recently it has become possible to query the great diversity of natural antibody repertoires using Next Generation Sequencing (NGS). These methods are capable of producing millions of sequences in a single experiment. Here we compare Clinical Stage Therapeutic antibodies to the ~1b sequences from 60 independent sequencing studies in the Observed Antibody Space Database. Of the 242 post Phase I antibodies, we find 16 with sequence identity matches of 95% or better for both heavy and light chains. There are also 54 perfect matches to therapeutic CDR-H3 regions in the NGS outputs, suggesting a nontrivial amount of convergence between naturally observed sequences and those developed artificially. This has potential implications for both the discovery of antibody therapeutics and the legal protection of commercial antibodies. Introduction Antibodies are proteins in jawed vertebrates that recognize noxious molecules (antigens) for elimination. An organism expresses millions of diverse antibodies to increase the chances that some of them will be able to bind the foreign antigen, initiating the adaptive immune response. -

MEDICAL JOURNAL Yongwen Jiang, Phd (USPS 464-820), a Monthly Publication, Is Deborah N

RHODE ISLAND M EDICAL J OURNAL Body Worlds Vital visits Rhode Island, page 66 R SPECIAL SECTION ADVANCES IN AUTOIMMUNE DISEASES GUEST EDITOR: EDWARD V. LALLY, MD DECember 2016 VOLUME 99 • NUMBER 12 ISSN 2327-2228 Your records are secure. Until they’re not. Data theft can happen to anyone, anytime. A misplaced mobile device can compromise your personal or patient records. RIMS IBC can get you the cyber liability insurance you need to protect yourself and your patients. Call us. 401-272-1050 IN COOPERATION WITH RIMS IBC RIMS INSURANCE BROKERAGE CORPORATION 405 PROMENADE STREET, SUITE B, PROVIDENCE RI 02908-4811 MEDICAL PROFESSIONAL/ CYBER LIABILITY PROPERTY/ CASUALTY LIFE/HEALTH/ DISABILITY RHODE ISLAND M EDICAL J OURNAL 18 Newer Treatment Strategies for Autoimmune Diseases EDWARD V. LALLY, MD GUEST EDITOR E. Lally, MD 19 Targeted Immunomodulatory Therapy: An Overview ASHLEY L. LEFEBVRE, PharmD, CDOE LAURA MCAULIFFE, PharmD: PGY2 23 Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: A. Lefebvre, PharmD A Review of the Clinical Approach to Diagnosis and Update on Current Targeted Therapies JOANNE SZCZYGIEL CUNHA, MD KATARZYNA GILEK-SEIBERT, MD J. Cunha, MD 28 Pemphigus: Pathogenesis to Treatment K. Gilek-Siebert, MD CHRISTOPHER DIMARCO, MD 32 Chronic Inflammatory Demyelinating Polyradiculoneuropathy (CIDP): C. DiMarco, MD Clinical Features, Diagnosis, and Current Treatment Strategies JACQUES REYNOLDS, DO GEORGE SACHS, MD, PhD G. Sachs, MD, PhD KARA STavROS, MD 36 Autoimmune Cytopenias: Diagnosis & Management CHRISTIAN P. NIXON, MD, PhD JOSEPH D. SWEENEY, MD C. Nixon, MD, PhD RHODE ISLAND M EDICAL J OURNAL 8 COMMENTARY Medical Tourism JOSEPH H. FRIEDMAN, MD Dickensian Diagnostics: The Diseases of Christmas Past What ailed Scrooge and Tiny Tim? HERBERT RAKATANSKY, MD Reconnecting with my Purpose in the Kingdom of Bhutan ERIC COHEN, MD 17 RIMJ AROUND THE WORLD New York, New York 58 RIMS NEWS Are you reading RIMS Notes? Working for You Weight + Wellness Summit Why You Should Join RIMS 66 SPOTLIGHT Body Worlds Exhibit: Anatomy Up Close & Personal MARY KORR 78 HeritaGE Dec. -

The Role of Tumor Necrosis Factor Alpha (TNF-)

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Review The Role of Tumor Necrosis Factor Alpha (TNF-α) in Autoimmune Disease and Current TNF-α Inhibitors in Therapeutics Dan-in Jang 1,†, A-Hyeon Lee 1,† , Hye-Yoon Shin 2, Hyo-Ryeong Song 1,3 , Jong-Hwi Park 1, Tae-Bong Kang 4 , Sang-Ryong Lee 5,* and Seung-Hoon Yang 1,* 1 Department of Medical Biotechnology, Collage of Life Science and Biotechnology, Dongguk University, Seoul 04620, Korea; [email protected] (D.-i.J.); [email protected] (A.-H.L.); [email protected] (H.-R.S.); [email protected] (J.-H.P.) 2 School of Life Science, Handong Global University, Pohang, Gyeongbuk 37554, Korea; [email protected] 3 Department of Pharmacy, College of Pharmacy, Yonsei University, Seoul 03722, Korea 4 Department of Biotechnology, College of Biomedical and Health Science, Konkuk University, Chungju 27478, Korea; [email protected] 5 Department of Biological Environmental Science, Collage of Life Science and Biotechnology, Dongguk University, Seoul 04620, Korea * Correspondence: [email protected] (S.-R.L.); [email protected] (S.-H.Y.) † These authors contributed equally to this work. Abstract: Tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) was initially recognized as a factor that causes the Citation: Jang, D.-i.; Lee, A-H.; Shin, necrosis of tumors, but it has been recently identified to have additional important functions as a H.-Y.; Song, H.-R.; Park, J.-H.; Kang, pathological component of autoimmune diseases. TNF-α binds to two different receptors, which T.-B.; Lee, S.-R.; Yang, S.-H. The Role initiate signal transduction pathways. -

Immunfarmakológia Immunfarmakológia

Gergely: Immunfarmakológia Immunfarmakológia Prof Gergely Péter Az immunpatológiai betegségek döntő többsége gyulladásos, és ennek következtében általában szövetpusztulással járó betegség, melyben – jelenleg – a terápia alapvetően a gyulladás csökkentésére és/vagy megszűntetésére irányul. Vannak kizárólag gyulladásgátló gyógyszereink és vannak olyanok, amelyek az immunreakció(k) bénításával (=immunszuppresszió révén) vagy emellett vezetnek a gyulladás mérsékléséhez. Mind szerkezetileg, mind hatástanilag igen sokféle csoportba oszthatók, az alábbi felosztás elsősorban didaktikus célokat szolgál. 1. Nem-szteroid gyulladásgátlók (‘nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs’ NSAID) 2. Kortikoszteroidok 3. Allergia-elleni szerek (antiallergikumok) 4. Sejtoszlás-gátlók (citosztatikumok) 5. Nem citosztatikus hatású immunszuppresszív szerek 6. Egyéb gyulladásgátlók és immunmoduláns szerek 7. Biológiai terápia 1. Nem-szteroid gyulladásgátlók (NSAID) Ezeket a vegyületeket, melyek őse a szalicilsav (jelenleg, mint acetilszalicilsav ‘aszpirin’ használatos), igen kiterjedten alkalmazzák a reumatológiában, az onkológiában és az orvostudomány szinte minden ágában, ahol fájdalom- és lázcsillapításra van szükség. Egyes felmérések szerint a betegek egy ötöde szed valamilyen NSAID készítményt. Szerkezetük alapján a készítményeket több csoportba sorolhatjuk: szalicilátok (pl. acetilszalicilsav) pyrazolidinek (pl. fenilbutazon) ecetsav származékok (pl. indometacin) fenoxiecetsav származékok (pl. diclofenac, aceclofenac)) oxicamok (pl. piroxicam, meloxicam) propionsav -

Antibodies to Watch in 2021 Hélène Kaplona and Janice M

MABS 2021, VOL. 13, NO. 1, e1860476 (34 pages) https://doi.org/10.1080/19420862.2020.1860476 PERSPECTIVE Antibodies to watch in 2021 Hélène Kaplona and Janice M. Reichert b aInstitut De Recherches Internationales Servier, Translational Medicine Department, Suresnes, France; bThe Antibody Society, Inc., Framingham, MA, USA ABSTRACT ARTICLE HISTORY In this 12th annual installment of the Antibodies to Watch article series, we discuss key events in antibody Received 1 December 2020 therapeutics development that occurred in 2020 and forecast events that might occur in 2021. The Accepted 1 December 2020 coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic posed an array of challenges and opportunities to the KEYWORDS healthcare system in 2020, and it will continue to do so in 2021. Remarkably, by late November 2020, two Antibody therapeutics; anti-SARS-CoV antibody products, bamlanivimab and the casirivimab and imdevimab cocktail, were cancer; COVID-19; Food and authorized for emergency use by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the repurposed Drug Administration; antibodies levilimab and itolizumab had been registered for emergency use as treatments for COVID-19 European Medicines Agency; in Russia and India, respectively. Despite the pandemic, 10 antibody therapeutics had been granted the immune-mediated disorders; first approval in the US or EU in 2020, as of November, and 2 more (tanezumab and margetuximab) may Sars-CoV-2 be granted approvals in December 2020.* In addition, prolgolimab and olokizumab had been granted first approvals in Russia and cetuximab saratolacan sodium was first approved in Japan. The number of approvals in 2021 may set a record, as marketing applications for 16 investigational antibody therapeutics are already undergoing regulatory review by either the FDA or the European Medicines Agency. -

WO 2016/176089 Al 3 November 2016 (03.11.2016) P O P C T

(12) INTERNATIONAL APPLICATION PUBLISHED UNDER THE PATENT COOPERATION TREATY (PCT) (19) World Intellectual Property Organization International Bureau (10) International Publication Number (43) International Publication Date WO 2016/176089 Al 3 November 2016 (03.11.2016) P O P C T (51) International Patent Classification: BZ, CA, CH, CL, CN, CO, CR, CU, CZ, DE, DK, DM, A01N 43/00 (2006.01) A61K 31/33 (2006.01) DO, DZ, EC, EE, EG, ES, FI, GB, GD, GE, GH, GM, GT, HN, HR, HU, ID, IL, IN, IR, IS, JP, KE, KG, KN, KP, KR, (21) International Application Number: KZ, LA, LC, LK, LR, LS, LU, LY, MA, MD, ME, MG, PCT/US2016/028383 MK, MN, MW, MX, MY, MZ, NA, NG, NI, NO, NZ, OM, (22) International Filing Date: PA, PE, PG, PH, PL, PT, QA, RO, RS, RU, RW, SA, SC, 20 April 2016 (20.04.2016) SD, SE, SG, SK, SL, SM, ST, SV, SY, TH, TJ, TM, TN, TR, TT, TZ, UA, UG, US, UZ, VC, VN, ZA, ZM, ZW. (25) Filing Language: English (84) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every (26) Publication Language: English kind of regional protection available): ARIPO (BW, GH, (30) Priority Data: GM, KE, LR, LS, MW, MZ, NA, RW, SD, SL, ST, SZ, 62/154,426 29 April 2015 (29.04.2015) US TZ, UG, ZM, ZW), Eurasian (AM, AZ, BY, KG, KZ, RU, TJ, TM), European (AL, AT, BE, BG, CH, CY, CZ, DE, (71) Applicant: KARDIATONOS, INC. [US/US]; 4909 DK, EE, ES, FI, FR, GB, GR, HR, HU, IE, IS, IT, LT, LU, Lapeer Road, Metamora, Michigan 48455 (US). -

Ep 3178848 A1

(19) TZZ¥__T (11) EP 3 178 848 A1 (12) EUROPEAN PATENT APPLICATION (43) Date of publication: (51) Int Cl.: 14.06.2017 Bulletin 2017/24 C07K 16/28 (2006.01) A61K 39/395 (2006.01) C07K 16/30 (2006.01) (21) Application number: 15198715.3 (22) Date of filing: 09.12.2015 (84) Designated Contracting States: (72) Inventor: The designation of the inventor has not AL AT BE BG CH CY CZ DE DK EE ES FI FR GB yet been filed GR HR HU IE IS IT LI LT LU LV MC MK MT NL NO PL PT RO RS SE SI SK SM TR (74) Representative: Cueni, Leah Noëmi et al Designated Extension States: F. Hoffmann-La Roche AG BA ME Patent Department Designated Validation States: Grenzacherstrasse 124 MA MD 4070 Basel (CH) (71) Applicant: F. Hoffmann-La Roche AG 4070 Basel (CH) (54) TYPE II ANTI-CD20 ANTIBODY FOR REDUCING FORMATION OF ANTI-DRUG ANTIBODIES (57) The present invention relates to methods of treating a disease, and methods for reduction of the formation of anti-drug antibodies (ADAs) in response to the administration of a therapeutic agent comprising administration of a Type II anti-CD20 antibody, e.g. obinutuzumab, to the subject prior to administration of the therapeutic agent. EP 3 178 848 A1 Printed by Jouve, 75001 PARIS (FR) EP 3 178 848 A1 Description Field of the Invention 5 [0001] The present invention relates to methods of treating a disease, and methods for reduction of the formation of anti-drug antibodies (ADAs) in response to the administration of a therapeutic agent. -

(INN) for Biological and Biotechnological Substances

INN Working Document 05.179 Update 2013 International Nonproprietary Names (INN) for biological and biotechnological substances (a review) INN Working Document 05.179 Distr.: GENERAL ENGLISH ONLY 2013 International Nonproprietary Names (INN) for biological and biotechnological substances (a review) International Nonproprietary Names (INN) Programme Technologies Standards and Norms (TSN) Regulation of Medicines and other Health Technologies (RHT) Essential Medicines and Health Products (EMP) International Nonproprietary Names (INN) for biological and biotechnological substances (a review) © World Health Organization 2013 All rights reserved. Publications of the World Health Organization are available on the WHO web site (www.who.int ) or can be purchased from WHO Press, World Health Organization, 20 Avenue Appia, 1211 Geneva 27, Switzerland (tel.: +41 22 791 3264; fax: +41 22 791 4857; e-mail: [email protected] ). Requests for permission to reproduce or translate WHO publications – whether for sale or for non-commercial distribution – should be addressed to WHO Press through the WHO web site (http://www.who.int/about/licensing/copyright_form/en/index.html ). The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the World Health Organization concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dotted lines on maps represent approximate border lines for which there may not yet be full agreement. The mention of specific companies or of certain manufacturers’ products does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by the World Health Organization in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. -

Rheumatoid Arthritis Market to 2020 - a Crowded Market Characterized by Modest Growth

THERAPY ANALYSIS Rheumatoid Arthritis Market to 2020 - A Crowded Market Characterized by Modest Growth Published: December 2014 Report Code: GBIHC354MR www.gbiresearch.com GBI Research Report Guidance The report begins with an executive summary detailing the key points driving the RA market in eight key developed markets: the US, the UK, Canada, France, Germany, Spain, Italy and Japan. Chapter two provides an introduction to RA, detailing the etiology, epidemiology, diagnostic techniques, disease staging and typical prognoses for patients. An analysis of current treatment algorithms and options is also included. Chapter three offers detailed analysis of the drugs currently marketed for this indication: MTX, Remicade, Humira, Enbrel, Rituxan, Orencia, Simponi Cimzia and Xeljanz. It includes key characteristics, covering safety and efficacy, clinical trial outcomes, tolerability, dosing, administration, historical sales, prices and overall competitive strength. These products are also compared in a comprehensive heat map. Chapter four provides detailed analysis of the pipeline for RA, by stage of development, molecule type, program type, mechanism of action and molecular target. It also analyzes recent clinical trials in this indication, by enrollment, duration and failure rate. Finally, promising late- stage pipeline molecules are analyzed and assessed in terms of their potential competitive strength. Chapter five analyzes the clinical trials conducted since 2006 in this indication, by enrollment, duration and failure rate. Promising late-stage pipeline molecules are analyzed and assessed in terms of their potential competitive strength. Chapter six supplies forecasts for the RA market, including epidemiology, treatment use patterns, pricing, and market size, for the 2013–2020 period. The markets are covered and data are presented at a country level with further analysis of key market drivers and barriers.