HISTORY Sir Neville Howse (VC), Private John Simpson Kirkpatrick

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Samai King Gifted and Talented Online Anzac Day: Why the Other Eight Months Deserve the Same Recognition As the Landing

THE Simpson PRIZE A COMPETITION FOR YEAR 9 AND 10 STUDENTS 2016 Winner Western Australia Samai King Gifted and Talented Online Anzac Day: Why The Other Eight Months Deserve The Same Recognition As The Landing Samai King Gifted and Talented Online rom its early beginnings in 1916, Anzac Day and the associated Anzac legend have come to be an essential part of Australian culture. Our history of the Gallipoli campaign lacks a consensus view as there are many Fdifferent interpretations and accounts competing for our attention. By far the most well-known event of the Gallipoli campaign is the landing of the ANZAC forces on the 25th of April, 1915. Our celebration of, and obsession with, just one single day of the campaign is a disservice to the memory of the men and women who fought under the Anzac banner because it dismisses the complexity and drudgery of the Gallipoli campaign: the torturous trenches and the ever present fear of snipers. Our ‘Anzac’ soldier is a popularly acclaimed model of virtue, but is his legacy best represented by a single battle? Many events throughout the campaign are arguably more admirable than the well-lauded landing, for example the Battle for Lone Pine. Almost four times as many men died in the period of the Battle of Lone Pine than during the Landing. Statistics also document the surprisingly successful evacuation - they lost not even a single soldier to combat. We have become so enamored by the ‘Landing’ that it is now more celebrated and popular than Remembrance Day which commemorates the whole of the First World War in which Anzacs continued to serve. -

NEWSLETTER 2/2014 SEPTEMBER 2014 About but Had the Suitable Nightmares Associated with War the Duntroon Story and the and Death

NEWSLETTER 2/2014 SEPTEMBER 2014 about but had the suitable nightmares associated with war The Duntroon Story and the and death. Bridges Family A couple of years later my father was awarded the MBE, and remembering his comment that Bridges men only Peter Bridges survive one war with or without medals, I naively asked him if this was because he had been wounded in the war—in Charles Bean, in his 1957 work ‘Two Men I Knew’, WW2. He told me that the MBE medal was not for war time reflected that Major General Sir William Throsby Bridges achievements but for peace time achievements. As an eight- laid two foundations of Australia’s fighting forces in WWI— year old this seemed very odd that someone who worked Duntroon and the 1st Division. Many officers and soldiers in hard got medals. I still firmly believed you got medals for our Army have served in both these enduring institutions being enormously brave in war time. It didn’t make sense to and one might suspect, more than occasionally, reflected on me so I asked him why Bridges men died in war and he was Bridges significant legacy in each. still alive. The story then came out. I had the great pleasure to welcome Dr Peter Bridges to His grandfather, the General (WTB), had fought in the Duntroon in 2003 and from that visit, the College held for a Boer war in South Africa (against my mother’s grandfather decade, and to its Centenary, the medals of its Founder. The as it turns out) and had been wounded in the relief of willingness of Peter and the greater Bridges family to lend a Kimberley. -

Anzac Day Media Style Guide - Centenary Edition 2016

Anzac Day Media Style Guide - Centenary Edition 2016 Contents (click on the headings below to navigate the guide) Foreword to the 2016 edition ........................................................................................................................................... 5 Foreword to the 2015 edition ........................................................................................................................................... 6 About this Guide ............................................................................................................................................................... 7 Editorial Advisory Board................................................................................................................................................ 8 Further Acknowledgements .......................................................................................................................................... 9 Your Feedback is Welcome ........................................................................................................................................... 9 Getting Started ................................................................................................................................................................ 10 Anzac/ANZAC .............................................................................................................................................................. 10 Anzac Day or ANZAC Day? ......................................................................................................................................... -

Anzac Day 2015

RESEARCH PAPER SERIES, 2014-15 UPDATED 16 APRIL 2015 Anzac Day 2015 David Watt Foreign Affairs, Defence and Security Section This ‘Anzac Day Kit’ has been compiled over a number of years by various staff members of the Parliamentary Library, and is updated annually. In particular the Library would like to acknowledge the work of John Moremon and Laura Rayner, both of whom contributed significantly to the original text and structure of the Kit. Nathan Church and Stephen Fallon contributed to the 2015 edition of this publication. Contents Introduction ................................................................................................ 4 What is this kit? .................................................................................................. 4 Section 1: Speeches ..................................................................................... 4 Previous Anzac Day speeches ............................................................................. 4 90th anniversary of the Anzac landings—25 April 2005 .................................... 4 Tomb of the Unknown Soldier............................................................................ 5 Ataturk’s words of comfort ................................................................................ 5 Section 2: The relevance of Anzac ................................................................ 5 Anzac—legal protection ..................................................................................... 5 The history of Anzac Day ................................................................................... -

The Great War Began at the End of July 1914 with the Triple Entente

ANZAC SURGEONS OF GALLIPOLI The Great War began at the end of July 1914 with the Triple Entente (Britain, France and Russia) aligned against the Triple Alliance (Germany, Austria- Hungary and Italy). By December, the Alliance powers had been joined by the Ottoman Turks; and in January 1915 the Russians, pressured by German and Turkish forces in the Caucasus, asked the British to open up another front. Hamilton second from right: There is nothing certain about war except that one side won’t win. AWM H10350 A naval campaign against Turkey was devised by the British The Turkish forces Secretary of State for War Lord Kitchener and the First Sea Lord, Winston Churchill. In 1913, Enver Pasha became Minister of War and de-facto Commander in Chief of the Turkish forces. He commanded It was intended that allied ships would destroy Turkish the Ottoman Army in 1914 when they were defeated by fortifications and open up the Straits of the Dardanelles, thus the Russians at the Battle of Sarikamiş and also forged the enabling the capture of Constantinople. alliance with Germany in 1914. In March 1915 he handed over control of the Ottoman 5th army to the German General Otto Liman von Sanders. It was intended that allied Von Sanders recognised the allies could not take Constantinople without a combined land and sea attack. ships would destroy Turkish In his account of the campaign, he commented on the small force of 60,000 men under his command but noted: The fortifications British gave me four weeks before their great landing. -

Of Victoria Cross Recipients by New South Wales State Electorate

Index of Victoria Cross Recipients by New South Wales State Electorate INDEX OF VICTORIA CROSS RECIPIENTS BY NEW SOUTH WALES STATE ELECTORATE COMPILED BY YVONNE WILCOX NSW Parliamentary Research Service Index of Victoria Cross recipients by New South Wales electorate (includes recipients who were born in the electorate or resided in the electorate on date of enlistment) Ballina Patrick Joseph Bugden (WWI) resided on enlistment ............................................. 36 Balmain William Mathew Currey (WWI) resided on enlistment ............................................. 92 John Bernard Mackey (WWII) born ......................................................................... 3 Joseph Maxwell (WWII) born .................................................................................. 5 Barwon Alexander Henry Buckley (WWI) born, resided on enlistment ................................. 8 Arthur Charles Hall (WWI) resided on enlistment .................................................... 26 Reginald Roy Inwood (WWI) resided on enlistment ................................................ 33 Bathurst Blair Anderson Wark (WWI) born ............................................................................ 10 John Bernard Mackey (WWII) resided on enlistment .............................................. ..3 Cessnock Clarence Smith Jeffries (WWI) resided on enlistment ............................................. 95 Clarence Frank John Partridge (WWII) born........................................................................... 13 -

Gettysburg National Military Park STUDENT PROGRAM

Gettysburg National Military Park STUDENT PROGRAM 1 Teachers’ Guide Table of Contents Purpose and Procedure ...................................3 FYI ...BackgroundInformationforTeachersandStudents CausesoftheAmericanCivilWar .........................5 TheBattleofGettysburg .................................8 CivilWarMedicalVocabulary ...........................12 MedicalTimeline ......................................14 Before Your Field Trip The Oath of Allegiance and the Hippocratic Oath ...........18 Squad #1 Activities — Camp Doctors .....................19 FieldTripIdentities .........................20 "SickCall"Play..............................21 CampDoctorsStudyMaterials ................23 PicturePages ...............................25 Camp Report — SickCallRegister .............26 Squad #2 Activities — BattlefieldDoctors .................27 FieldTripIdentities .........................28 "Triage"Play ...............................29 BattlefieldStudyMaterials ...................30 Battle Report — FieldHospitalRegister ........32 Squad #3 Activities — HospitalDoctors ...................33 FieldTripIdentities .........................34 "Hospital"Play..............................35 HospitalStudyMaterials(withPicturePages) ...37 Hospital Report — CertificateofDisability .....42 Your Field Trip Day FieldTripDayProcedures ..............................43 OverviewoftheFieldTrip ..............................44 Nametags .............................................45 After Your Field Trip SuggestedPost-VisitActivities ...........................46 -

'Feed the Troops on Victory': a Study of the Australian

‘FEED THE TROOPS ON VICTORY’: A STUDY OF THE AUSTRALIAN CORPS AND ITS OPERATIONS DURING AUGUST AND SEPTEMBER 1918. RICHARD MONTAGU STOBO Thesis prepared in requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Humanities and Social Sciences University of New South Wales, Canberra June 2020 Thesis/Dissertation Sheet Surname/Family Name : Stobo Given Name/s : Richard Montagu Abbreviation for degree as given in the : PhD University calendar Faculty : History School : Humanities and Social Sciences ‘Feed the Troops on Victory’: A Study of the Australian Corps Thesis Title : and its Operations During August and September 1918. Abstract 350 words maximum: (PLEASE TYPE) This thesis examines reasons for the success of the Australian Corps in August and September 1918, its final two months in the line on the Western Front. For more than a century, the Corps’ achievements during that time have been used to reinforce a cherished belief in national military exceptionalism by highlighting the exploits and extraordinary fighting ability of the Australian infantrymen, and the modern progressive tactical approach of their native-born commander, Lieutenant-General Sir John Monash. This study re-evaluates the Corps’ performance by examining it at a more comprehensive and granular operational level than has hitherto been the case. What emerges is a complex picture of impressive battlefield success despite significant internal difficulties that stemmed from the particularly strenuous nature of the advance and a desperate shortage of manpower. These played out in chronic levels of exhaustion, absenteeism and ill-discipline within the ranks, and threatened to undermine the Corps’ combat capability. In order to reconcile this paradox, the thesis locates the Corps’ performance within the wider context of the British army and its operational organisation in 1918. -

Australia in the League of Nations: a Centenary View

RESEARCH PAPER SERIES, 2018–19 21 DECEMBER 2018 Australia in the League of Nations: a centenary view James Cotton Emeritus Professor of Politics, University of New South Wales, ADFA, Canberra Contents The League and global politics beyond the Empire-Commonwealth . 2 The requirements of membership ...................................................... 3 The Australian experience as a League mandatory ............................ 4 Peace, disarmament, collective security ............................................. 6 The League and the management of international trade and economic policy ................................................................................ 10 The League’s social agenda ............................................................... 11 Geneva as a school for international affairs for some prominent Australians ......................................................................................... 12 The Australian League of Nations Union........................................... 13 The League idea in Australia ............................................................. 14 Discussion of the League in the parliament and the debate on foreign affairs .................................................................................... 16 Conclusions: Australia in the League ................................................ 19 ISSN 2203-5249 The League and global politics beyond the Empire-Commonwealth With the formation of the Australian Commonwealth, the new nation adopted a constitution that imparted to the -

The Simpson Prize: History Or Civics? Table of Contents

1 The Simpson Prize: history or civics? David Stephens and Steve Flora Table of contents What is the Simpson Prize?................................................................................................................. 1 What questions are asked? ................................................................................................................. 2 Who runs the Prize? ............................................................................................................................ 3 Which schools have entered students for the Prize? ......................................................................... 3 How many students have entered for the Prize? ............................................................................... 4 Which schools have provided the winners of the Prize? .................................................................... 4 What is the standard of entries? ........................................................................................................ 6 What is the significance of the 2015 question? .................................................................................. 8 What is the future of the Prize? .......................................................................................................... 9 Conclusion ......................................................................................................................................... 10 Appendix: Simpson Prize questions 1999-2014 ............................................................................... -

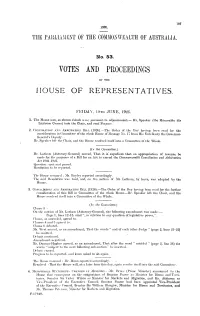

Votes and Proceedings House of Representatives

1926. THIE PA RLIAM L1NTr OF THE COMMON WEALTH OF AUSTRAL IA. No. 53. VOTES AND PROCEEDINGS OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES. [H IDAY 18,rI ni JUNE, 1926. 1. Thle House met, at eleven o'clock am., pursuant to adjournment.- Mr. Speaker (the Honorable Sir Littleton Groom) took the Chair, and read Pravers. 2. C'ONCILIATION AND) ARBITRATION BILL (1926)-The Order of thle lDay having beeni read for the consideration in ('ommittee of the whole House of Message No. 17 from His E xc~ellency the Governor- General's Deputy. -- .1r. Speaker left the ('hair, and the House resolved itself into a Committee of the Whole. (Int the Committee.) Mr. Latham (Attorney-General) moved, That it is' expedient that an appropriation of revenue be miade for the purposes of a Bill for anl Act to amend the Commovivealth Conciliation and Arbiteation Act 1.904 1921. Question--put amid passed. Itsoluitioll to lbe rep)orted. The Rouse resumied ;Mr. Bayley reported accordingly. The said Resolutioni was read, anid, onl the mnotion of iMr. Lathamln, by leave, wa~s adopted by the Hous'e; .3. CONCIIATION AND AiiBITRATION BILL (1926)-The Order of the Day having been read for thle further Conlsiderationi of this B1ill in Committee of the whole House-Mfr. Speaiker left the Chair, and the Hfouse resolvedl itself into A Committee of the Whole. (1) the Committee.) Clause 3 -- Onl the notion of M11rLathiam (Attorneuy-General), the following amendment was made Page 1. lines 12-13. omlit "', inl relation to any question of legislative powe, ('lause, as a iende, I, agreedl to. -

Community Paramedicine: Higher Education As an Enabling Factor Peter O'meara La Trobe University, [email protected]

Australasian Journal of Paramedicine Volume 11 | Issue 2 Article 5 2014 Community paramedicine: higher education as an enabling factor Peter O'Meara La Trobe University, [email protected] Michel Ruest Renfrew County Paramedic Service Christine Stirling University of Tasmania Recommended Citation O'Meara, P., Ruest, M., & Stirling, C. (2014). Community paramedicine: higher education as an enabling factor. Australasian Journal of Paramedicine, 11(2). Retrieved from http://ro.ecu.edu.au/jephc/vol11/iss2/5 This Journal Article is posted at Research Online. http://ro.ecu.edu.au/jephc/vol11/iss2/5 O'Meara et al.: Educating community paramedics Australasian Journal of Paramedicine: 2014:11(2) Original Research Community paramedicine: Higher education as an enabling factor 1Peter O’Meara PhD, 2Michel Ruest, 3Christine Stirling PhD Affiliations: 1 LaTrobe University, Victoria, Australia. 2 Renfrew County Paramedic Service, 3 University of Tasmania, Tasmania, Australia SUMMARY The aim of this case study was to describe one rural community paramedic model and identify enablers related to the implementation of the model. It was undertaken in the County of Renfrew, Ontario, Canada where a community paramedicine role has emerged in response to demographic changes and broader health system reform. Qualitative data was collected through direct observation of practice, informal discussions, interviews and focus groups. The crucial role of education in the effective and sustainable implementation of the community paramedicine model was identified as one of four enablers. Traditional paramedicine education programs are narrowly focused on emergency response, with limited education in health promotion, aged care and chronic disease management. Educational programs hoping to include a wider range of topics face the twin challenges of an already crowded curriculum and predominately young students who fail to see the relevance of community primary care content.