A Conversation with Shashi Tharoor Interview by Ragini Tharoor Srinivasan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

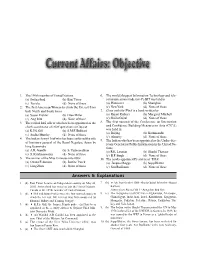

Higher Secondary: SET

RRB PSC Higher Secondary: SET 1. The 190th member of United Nations 6. The world’s biggest Information Technology and tele- (a) Switzerland (b) East Timor communications trade fair-Ce BIT was held in (c) Tuvalu (d) None of these (a) Hannover (b) Shanghai 2. The first American Woman to climb the Everest from (c) New York (d) None of these both North and South faces 7. Gone with the Wind is a book written by (a) Susan Ershler (b) Ellen Miller (a) Rajani Kothari (b) Margaret Mitchell (c) Ang Rita (d) None of these (c) Sheila Gujral (d) None of these 3. The retired IAS officer who has been appointed as the 8. The first summit of the Conference on Interaction chief co-ordinator of relief operations in Gujarat and Confidence Building Measures in Asia (CICA) (a) K.P.S. Gill (b) S.M.F. Bokhari was held in (a) Beijing (b) Kathmandu (c) Sudha Murthy (d) None of these (c) Almatty (d) None of these 4. The Indian Army Chief who has been conferred the title 9. The Indian who has been appointed as the Under-Sec- of honorary general of the Royal Nepalese Army by retary General for Public Information in the United Na- king Gyanendra tions. (a) A.R. Gandhi (b) S. Padmanabhan (a) R.K. Laxman (b) Shashi Tharoor (c) S. Krishnaswamy (d) None of these (c) B.P. Singh (d) None of these 5. The winner of the Miss Universe title 2002 10. The newly appointed President of ‘FIFA’ (a) Oxana Fedorova (b) Justine Pasek (a) Jacques Rogge (b) Sepp Blatter (c) Ling Zhou (d) None of these (c) Sen Ruffianne (d) None of these Answers & Explanations 1. -

Library Catalogue

Id Access No Title Author Category Publisher Year 1 9277 Jawaharlal Nehru. An autobiography J. Nehru Autobiography, Nehru Indraprastha Press 1988 historical, Indian history, reference, Indian 2 587 India from Curzon to Nehru and after Durga Das Rupa & Co. 1977 independence historical, Indian history, reference, Indian 3 605 India from Curzon to Nehru and after Durga Das Rupa & Co. 1977 independence 4 3633 Jawaharlal Nehru. Rebel and Stateman B. R. Nanda Biography, Nehru, Historical Oxford University Press 1995 5 4420 Jawaharlal Nehru. A Communicator and Democratic Leader A. K. Damodaran Biography, Nehru, Historical Radiant Publlishers 1997 Indira Gandhi, 6 711 The Spirit of India. Vol 2 Biography, Nehru, Historical, Gandhi Asia Publishing House 1975 Abhinandan Granth Ministry of Information and 8 454 Builders of Modern India. Gopal Krishna Gokhale T.R. Deogirikar Biography 1964 Broadcasting Ministry of Information and 9 455 Builders of Modern India. Rajendra Prasad Kali Kinkar Data Biography, Prasad 1970 Broadcasting Ministry of Information and 10 456 Builders of Modern India. P.S.Sivaswami Aiyer K. Chandrasekharan Biography, Sivaswami, Aiyer 1969 Broadcasting Ministry of Information and 11 950 Speeches of Presidente V.V. Giri. Vol 2 V.V. Giri poitical, Biography, V.V. Giri, speeches 1977 Broadcasting Ministry of Information and 12 951 Speeches of President Rajendra Prasad Vol. 1 Rajendra Prasad Political, Biography, Rajendra Prasad 1973 Broadcasting Eminent Parliamentarians Monograph Series. 01 - Dr. Ram Manohar 13 2671 Biography, Manohar Lohia Lok Sabha 1990 Lohia Eminent Parliamentarians Monograph Series. 02 - Dr. Lanka 14 2672 Biography, Lanka Sunbdaram Lok Sabha 1990 Sunbdaram Eminent Parliamentarians Monograph Series. 04 - Pandit Nilakantha 15 2674 Biography, Nilakantha Lok Sabha 1990 Das Eminent Parliamentarians Monograph Series. -

Current Affairs Questions and Answers for February 2010: 1. Which Bollywood Film Is Set to Become the First Indian Film to Hit T

ho”. With this latest honour the Mozart of Madras joins Current Affairs Questions and Answers for other Indian music greats like Pandit Ravi Shankar, February 2010: Zakir Hussain, Vikku Vinayak and Vishwa Mohan Bhatt who have won a Grammy in the past. 1. Which bollywood film is set to become the first A. R. Rahman also won Two Academy Awards, four Indian film to hit the Egyptian theaters after a gap of National Film Awards, thirteen Filmfare Awards, a 15 years? BAFTA Award, and Golden Globe. Answer: “My Name is Khan”. 9. Which bank became the first Indian bank to break 2. Who becomes the 3rd South African after Andrew into the world’s Top 50 list, according to the Brand Hudson and Jacques Rudoph to score a century on Finance Global Banking 500, an annual international Test debut? ranking by UK-based Brand Finance Plc, this year? Answer: Alviro Petersen Answer: The State Bank of India (SBI). 3. Which Northeastern state of India now has four HSBC retain its top slot for the third year and there are ‘Chief Ministers’, apparently to douse a simmering 20 Indian banks in the Brand Finance® Global Banking discontent within the main party in the coalition? 500. Answer: Meghalaya 10. Which country won the African Cup of Nations Veteran Congress leader D D Lapang had assumed soccer tournament for the third consecutive time office as chief minister on May 13, 2009. He is the chief with a 1-0 victory over Ghana in the final in Luanda, minister with statutory authority vested in him. -

English Books in Ksa Library

Author Title Call No. Moss N S ,Ed All India Ayurvedic Directory 001 ALL/KSA Jagadesom T D AndhraPradesh 001 AND/KSA Arunachal Pradesh 001 ARU/KSA Bullock Alan Fontana Dictionary of Modern Thinkers 001 BUL/KSA Business Directory Kerala 001 BUS/KSA Census of India 001 CEN/KSA District Census handbook 1 - Kannanore 001 CEN/KSA District Census handbook 9 - Trivandrum 001 CEN/KSA Halimann Martin Delhi Agra Fatepur Sikri 001 DEL/KSA Delhi Directory of Kerala 001 DEL/KSA Diplomatic List 001 DIP/KSA Directory of Cultural Organisations in India 001 DIR/KSA Distribution of Languages in India 001 DIS/KSA Esenov Rakhim Turkmenia :Socialist Republic of the Soviet Union 001 ESE/KSA Evans Harold Front Page History 001 EVA/KSA Farmyard Friends 001 FAR/KSA Gazaetteer of India : Kerala 001 GAZ/KSA Gazetteer of India 4V 001 GAZ/KSA Gazetteer of India : kerala State Gazetteer 001 GAZ/KSA Desai S S Goa ,Daman and Diu ,Dadra and Nagar Haveli 001 GOA/KSA Gopalakrishnan M,Ed Gazetteers of India: Tamilnadu State 001 GOP/KSA Allward Maurice Great Inventions of the World 001 GRE/KSA Handbook containing the Kerala Government Servant’s 001 HAN/KSA Medical Attendance Rules ,1960 and the Kerala Governemnt Medical Institutions Admission and Levy of Fees Rules Handbook of India 001 HAN/KSA Ker Alfred Heros of Exploration 001 HER/KSA Sarawat H L Himachal Pradesh 001 HIM/KSA Hungary ‘77 001 HUN/KSA India 1990 001 IND/KSA India 1976 : A Reference Annual 001 IND/KSA India 1999 : A Refernce Annual 001 IND/KSA India Who’s Who ,1972,1973,1977-78,1990-91 001 IND/KSA India :Questions -

Indian Writing in English

INDIAN WRITING IN ENGLISH Contents 1) English in India 3 2) Indian Fiction in English: An Introduction 6 3) Raja Rao 32 4) Mulk Raj Anand 34 5) R K Narayan 36 6) Sri Aurobindo 38 7) Kamala Markandaya’s Indian Women Protagonists 40 8) Shashi Deshpande 47 9) Arun Joshi 50 10) The Shadow Lines 54 11) Early Indian English Poetry 57 a. Toru Dutt 59 b. Michael Madusudan Dutta 60 c. Sarojini Naidu 62 12) Contemporary Indian English Poetry 63 13) The Use of Irony in Indian English Poetry 68 14) A K Ramanujan 73 15) Nissim Ezekiel 79 16) Kamala Das 81 17) Girish Karnad as a Playwright 83 Vallaths TES 2 English in India I’ll have them fly to India for gold, Ransack the ocean for oriental pearl! These are the words of Dr. Faustus in Christopher Marlowe’s play Dr Faustus. The play was written almost in the same year as the East India Company launched upon its trading adventures in India. Marlowe’s words here symbolize the Elizabethan spirit of adventure. Dr. Faustus sells his soul to the devil, converts his knowledge into power, and power into an earthly paradise. British East India Company had a similar ambition, the ambition of power. The English came to India primarily as traders. The East India Company, chartered on 31 December, 1600, was a body of the most enterprising merchants of the City of London. Slowly, the trading organization grew into a ruling power. As a ruler, the Company thought of its obligation to civilize the natives; they offered their language by way of education in exchange for the loyalty and commitment of their subjects. -

January 2021)

MONTHLY CURRENT AFFAIRS FACTS COMPILATION (JANUARY 2021) 2021 is the International Year - For the Elimination of Child Labor Of Fruits and Vegetables Of Peace and Trust Of Creative Economy for Sustainable Development Important Days of January World Braille Day - January 4 World Day of War Orphans - January 6 Pravasi Bharatiya Divas (NRI Day) - January 9 National Human Trafficking Awareness Day - January 11 World Hindi Day is observed annually on - January 10 National Youth Day - January 12 Armed Forces Veterans Day - January 14 Army Day - January 15 World Religion Day - January 17 National Road Safety Month 2021 - 18 January to 17 February Parakram Diwas - January 23 National Girl Child Day - January 24 International Day of Education - January 24 National Tourism Day - January 25 National Voters Day - January 25 Republic Day - January 26 International Customs Day - January 26 International Day of Commemoration in Memory of the Victims of the Holocaust - January 27 Martyr’s Day or Shaheed Diwas - January 30 World Leprosy Day - Last Sunday of January (January 31, 2021) National India’s first pollinator park opens in - Uttarakhand India’s first city to have fulfilled 100% of its energy needs during day time with solar energy - Diu Corona virus vaccine developed by Oxford-AstraZeneca - Covishield The COVID-19 vaccine which was recently approved by WHO for immediate use - Pfizer BioNTech vaccine Two vaccines recently approved by the Drugs Controller General of India for “Restricted Emergency Use” in India - COVAXIN and COVISHIELD Which state government recently announced to set up a Tamil Academy to protect the Tamil language and culture? - Delhi The Indian city hosting the India-France joint Rafale Mega Air Exercise ‘SKYROS’ - Jodhpur The largest floating solar energy project in the world is to be constructed by the Govt. -

Journal Vol 2 Issue 2

a transdisciplinary biannual research journal Vol. 2 Issue 2 July 2015 Postgraduate Department of English Manjeri, Malappuram, Kerala. www.kahmunityenglish.in/journals/singularities/ Chief Editor P. K. Babu., Ph. D Associate Professor & Head Postgraduate Dept. of English KAHM Unity Women's College, Manjeri. Members: Dr. K. K. Kunhammad, Asst. Professor, Dept. of Studies in English, Kannur University Mammad. N, Asst. Professor, Dept of English, Govt. College, Malappuram. Dr. Priya. K. Nair, Asst. Professor, Dept. of English, St. Teresa's College, Eranakulam. Aswathi. M . P., Asst. Professor, Dept of English, KAHM Unity Women's College, Manjeri. Advisory Editors: Dr. V. C. Haris School of Letters, M.G. University Kottayam Dr. M. V. Narayanan, Assoc. Professor, Dept of English, University of Calicut. Editor's Note The Singularities is into its fourth issue since it was launched in the January 2014 as a transdisciplinary biannual research Journal. The team of teachers at the English Department of KAHM Unity Women's College, Manjeri, has ensured that the Journal is issued promptly within the time frame we have set for the Journal. Not only have we stuck to the mission, but we have contributed to building writing skill and awareness to Research Writing organising workshops and training sessions in quality writing. The current issue with its core on Film, Women and Literature, carries a range of articles connecting the theme at various nodes. The surge of interest in Films and Women seems to offer a lot to complement each other. There appears to be a lot of interest in Cinema but it seems this is slow in getting translated fully into quality writing from the youngsters. -

![DECLARATION of ASSETS Shashi Tharoor (Spouse Sunanda Pushkar Tharoor Listed Separately]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8684/declaration-of-assets-shashi-tharoor-spouse-sunanda-pushkar-tharoor-listed-separately-4088684.webp)

DECLARATION of ASSETS Shashi Tharoor (Spouse Sunanda Pushkar Tharoor Listed Separately]

DECLARATION OF ASSETS Shashi Tharoor (spouse Sunanda Pushkar Tharoor listed separately] (i) Cash and Deposits in banks, financial institutions and Non Banking Financial Companies in various currencies (US$, AED, DKK and INR): approximately Rs 2.5 crores (ii) Bonds, Debentures and Shares in Companies as per current market valuation in case of listed companies and Book Value for Unlisted Companies (in US$ and INR): approximately Rs 2.5 crores (iii) Agriculture Land : Double Crop Wet Land, Location - Elevanchery Village, Chittoor Taluk, Palakkad Dt., Kerala Survey No.: Block # 7, 245/9,14,16,17 Extent (Total Measurement): 1/4th Share of 2.51 Acres extending to 63 cents Current Market Value: Rs 1.56 lakhs (iv) Apartment in Kakkanad, Cochin (under construction) Re-Survey No. 245/1 Extent (Total Measurement) - 1.325%vUndivided Right in 75.24 Cents along with 1954.24 Sq. Ft, built up area, Apartment No. 9AB, BCG Residency Tower, Opp. CSEZ, Kakkanad Current Market Value: Rs 27 lakhs (v)1/11th share in the ancestral Family Property, "Mundarath House", Elavanchery, Palakkad District, Kerala, comprised in Survey No. 119/6 (Block # 7) having an extent of 42.250 cents along with a old residential building Current Market Value: Rs 0.8 lakh (vi) Residential Apartment in Thiruvananthapuram Current Market Value: Rs 65 lakhs (vii) Car: I own one car in Trivandrum, purchased in 2009 for Rs 8 lakhs, worth less today. I have sold my Delhi car, but my wife owns one (see separate statement). (viii) Jewellery: 1 gold chain, two gold rings, and 10 sets of cuff links, worth approximately Rs 10 lakhs. -

04 IS 2400 – Perspectives on India Fall 2018 Class Timings: 10.40Am-11.47Am MWF, Class Building: Mathematics and Science Center 185 Instructor: Dr

College of Arts and Sciences International Studies Program Oakland University Credits: 04 IS 2400 – Perspectives on India Fall 2018 Class timings: 10.40am-11.47am MWF, Class building: Mathematics and Science Center 185 Instructor: Dr. Shalini Jayaprakash Email: [email protected] Available by appointments Course Catalog Description: This course is an interdisciplinary study of the people of India and their traditional and modern civilization. It is designed to satisfy the university general education requirement in the global perspective knowledge exploration area. This course will give the students an idea of India, a civilization, whose past is well knitted into its present. This course will highlight the diverse traditions and depth of Indian culture, and also offer opportunities, through reading of its rich literature and movies, to understand its plurality. It also fulfills requirements in Writing. This class satisfies the General Education requirements Intensive in General Education (WIGE) General Education Learning Outcomes: 1. Student will demonstrate knowledge of environments, political systems, economies, societies and religions of one of more regions outside the United States and awareness of the transnational flow of goods, people, ideas and values. 2. Student will demonstrate knowledge of the role that different cultural heritages, past and present, playing forming values in another part of the world, enabling the student to function within a more global context. Cross-cutting Capacity: Social awareness, Critical thinking, Effective communication Course prerequisites: university writing foundation requirement (WRT 160), required for WIGE courses Required Primary Texts 1. Ganguly, Sumit, and Neil DeVotta. Understanding Contemporary India. Boulder, Colo: Lynne Rienner Publishers, 2003. Print. 2. -

Women in Pre- and Post-Victorian India: the Use of Historical Research in the Writing of Fiction

Radhika Praveen/05039123 Vol 1 of 2 Creative Writing PhD Vol 2 Women in pre- and post-Victorian India: The use of historical research in the writing of fiction by Radhika Praveen This practice-based thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of London Metropolitan University for a Doctorate of Philosophy degree in Creative Writing. September 2018 1 Radhika Praveen/05039123 Vol 1 of 2 Creative Writing PhD This work is dedicated to both my grandmothers, Devaki Amma, and Saroja Iyengar. A deep regret that I could not spend much time with my paternal grandmother, Devaki Amma (Achchamma), is probably reflected in my novel. Memories with her are few, but they will last forever. For my dear Ammamma, Saroja, who has always lamented the lack of formal education in her life: this doctorate is for you. 2 Radhika Praveen/05039123 Vol 1 of 2 Creative Writing PhD Abstract This practice-based creative writing doctorate supports the creation of a novel that is in part, historical fiction, based on research focusing on the discrepancies in the perceived status of women between the pre-Victorian and the postmillennial periods in India. The accompanying component of the doctorate, the analytical thesis, traces the course of this research in connection to the novel's structural development, its narrative complexity and its characters. The novel traces the journey of two women protagonists – each placed in the 18th- and the 21st-centuries, respectively – as they reconcile to the realities of their individual circumstances. The introduction to the critical thesis gives a brief synopsis of the novel. -

Impact Narratives in Indian English Diaspora

Journal of Education and Practice - Vol 2, No 2 www.iiste.org ISSN 2222-1735 (Paper) ISSN 2222-288X (Online) Impact Narratives in Indian English Diaspora Prof.H.L.Narayanrao M.A.(Eng.), PGJMC, PGDHE., Assistant Professor of English Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan’s College (Uniniversity of Mumbai) Munshi Nagar, Andheri(w) Mumbai-400058. India. Tel: 09869923600, [email protected] 1. Introduction Diaspora a word derived from Greek, meaning "scattering, dispersion" is the movement or migration of a group of people, such as those sharing a national and/or ethnic identity, away from an established or ancestral homeland. The first recorded usage of the word Diaspora in the English language was in 1876, later it became more widely assimilated into English by the mid 1950s, with long-term expatriates in significant numbers from other particular countries or regions also being referred to as a Diaspora. An academic field, Diaspora studies, has become established relating to this sense of the word. Most of the traditional values and cross-cultural arts, literature is being incorporated in the writings. 2. Indian writers in English In the previous century, several Indian writers have distinguished themselves not only in traditional Indian languages but also in English language. India's Nobel laureate in literature was the Bengali writer Rabindranath Tagore. Other major writers who are either Indian or of Indian origin and derive much inspiration from Indian themes are R K Narayan, Vikram Seth, Salman Rushdie, Arundhati Roy, Raja Rao, Amitav Ghosh, Vikram Chandra, Mukul Kesavan, Shashi Tharoor. Indian Women writers and poets like Kamala Das, in the feminist era in India by her bold and confessional writings. -

Myth, History and Historiography in Shashi Tharoor's the Great In

Raita Merivirta-Chakrabarti Reclaiming India’s History – Myth, History and Historiography in Shashi Tharoor’s The Great Indian Novel >>PDF-version It has been noted that “[o]ne of the most striking trends in the Indian novel in English has been its tendency to reclaim the nation’s histories.” [1] This is perhaps not too surprising if one considers that even until quite recently, till the publication and success of Salman Rushdie’s Midnight’s Children in 1981, it was the “Western” vision of (twentieth-century) India, or, at least, a vision created by Westerners, that remained dominant in the world of fiction written in English, as also in the academic arena Western formal and theoretical constructs of historiography were hegemonic in Indian history-writing until at least the beginning of the 1980s. While British representations of India, from Rudyard Kipling’s Kim to Paul Scott’s The Jewel in the Crown, from E. M. Forster’s A Passage to India to Richard Attenborough’s film Gandhi, were still dominant and Britain was going through a nostalgic Raj-revival period, as manifested in the plethora of television series and films made on the subject in the 1980s, Indian novelist Shashi Tharoor set out to present a (hi)story of India in the twentieth century from an Indian perspective to his western(ised) readership; and tapped, in the post-Rushdie visibility of the Indian English novel, into the possibility of foregrounding India in his The Great Indian Novel (1989). Tharoor himself has said of his writing: “my fiction seeks to reclaim my country’s