Journal Vol 2 Issue 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

KERALA SOLID WASTE MANAGEMENT PROJECT (KSWMP) with Financial Assistance from the World Bank

KERALA SOLID WASTE MANAGEMENT Public Disclosure Authorized PROJECT (KSWMP) INTRODUCTION AND STRATEGIC ENVIROMENTAL ASSESSMENT OF WASTE Public Disclosure Authorized MANAGEMENT SECTOR IN KERALA VOLUME I JUNE 2020 Public Disclosure Authorized Prepared by SUCHITWA MISSION Public Disclosure Authorized GOVERNMENT OF KERALA Contents 1 This is the STRATEGIC ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT OF WASTE MANAGEMENT SECTOR IN KERALA AND ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL MANAGEMENT FRAMEWORK for the KERALA SOLID WASTE MANAGEMENT PROJECT (KSWMP) with financial assistance from the World Bank. This is hereby disclosed for comments/suggestions of the public/stakeholders. Send your comments/suggestions to SUCHITWA MISSION, Swaraj Bhavan, Base Floor (-1), Nanthancodu, Kowdiar, Thiruvananthapuram-695003, Kerala, India or email: [email protected] Contents 2 Table of Contents CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION TO THE PROJECT .................................................. 1 1.1 Program Description ................................................................................. 1 1.1.1 Proposed Project Components ..................................................................... 1 1.1.2 Environmental Characteristics of the Project Location............................... 2 1.2 Need for an Environmental Management Framework ........................... 3 1.3 Overview of the Environmental Assessment and Framework ............. 3 1.3.1 Purpose of the SEA and ESMF ...................................................................... 3 1.3.2 The ESMF process ........................................................................................ -

Alumni Association of MS Ramaiah University of Applied Sciences

Alumni Association of M.S. Ramaiah University of Applied Sciences (SAMPARK), Bangalore M.S. Ramaiah University of Applied Sciences Department of Automotive & Aeronautical Engineering Program Year of Name Contact Address Photograph E-mail & Mobile Sl NO Completed Admiss ion # 25 Biligiri, 13th cross, 10th A Main, 2nd M T Layout, [email protected] M. Sc. (Automotive 574 2013 Pramod M Malleshwaram, Bangalore- 9916040325 Engineering) 560003 S/o L. Srinivas Rao, Sai [email protected] Dham, D-No -B-43, Near M. Sc. (Automotive m 573 2013 Lanka Vinay Rao Torwapool, Bilaspur (C.G)- Engineering) 9424148279 495001 9406114609 3-17-16, Ravikunj, Parwana Nagar, [email protected] Upendra M. Sc. (Automotive Khandeshwari road, Bank m 572 2013 Padmakar Engineering) colony, 7411330707 Kulkarni Dist - BEED, State – 8149705281 Maharastra No.33, 9th Cross street, Dr. Radha Krishna Nagar, [email protected] M. Sc. (Automotive Venkata Krishna Teachers colony, 571 2013 0413-2292660 Engineering) S Moolakulam, Puducherry-605010 # 134, 1st Main, Ist A cross central Excise Layout [email protected] M. Sc. (Automotive Bhoopasandra RMV Iind 570 2013 Anudeep K N om Engineering) stage, 9686183918 Bengaluru-560094 58/F, 60/2,Municipal BLDG, G. D> Ambekar RD. Parel [email protected] M. Sc. (Automotive Tekavde Nitin 569 2013 Bhoiwada Mumbai, om Engineering) Shivaji Maharashtra-400012 9821184489 Thiyyakkandiyil (H), [email protected] M. Sc. (Automotive Nanminda (P.O), Kozhikode / 568 2013 Sreedeep T K m Engineering) Kerala – 673613 4952855366 #108/1, 9th Cross, themightyone.lohith@ M. Sc. (Automotive Lakshmipuram, Halasuru, 567 2013 Lohith N gmail.com Engineering) Bangalore-560008 9008022712 / 23712 5-8-128, K P Reddy Estates,Flat No.A4, indu.vanamala@gmail. -

Structuralism 1. the Nature of Meaning Or Understanding

Structuralism 1. The nature of meaning or understanding. A. The role of structure as the system of relationships Something can only be understood (i.e., a meaning can be constructed) within a certain system of relationships (or structure). For example, a word which is a linguistic sign (something that stands for something else) can only be understood within a certain conventional system of signs, which is language, and not by itself (cf. the word / sound and “shark” in English and Arabic). A particular relationship within a شرق combination society (e.g., between a male offspring and his maternal uncle) can only be understood in the context of the whole system of kinship (e.g., matrilineal or patrilineal). Structuralism holds that, according to the human way of understanding things, particular elements have no absolute meaning or value: their meaning or value is relative to other elements. Everything makes sense only in relation to something else. An element cannot be perceived by itself. In order to understand a particular element we need to study the whole system of relationships or structure (this approach is also exactly the same as Malinowski’s: one cannot understand particular elements of culture out of the context of that culture). A particular element can only be studied as part of a greater structure. In fact, the only thing that can be studied is not particular elements or objects but relationships within a system. Our human world, so to speak, is made up of relationships, which make up permanent structures of the human mind. B. The role of oppositions / pairs of binary oppositions Structuralism holds that understanding can only happen if clearly defined or “significant” (= essential) differences are present which are called oppositions (or binary oppositions since they come in pairs). -

CLAUDE LEVI-STRAUSS: the Man and His Works

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Nebraska Anthropologist Anthropology, Department of 1977 CLAUDE LEVI-STRAUSS: The Man and His Works Susan M. Voss University of Nebraska-Lincoln Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/nebanthro Part of the Anthropology Commons Voss, Susan M., "CLAUDE LEVI-STRAUSS: The Man and His Works" (1977). Nebraska Anthropologist. 145. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/nebanthro/145 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Anthropology, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Nebraska Anthropologist by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Published in THE NEBRASKA ANTHROPOLOGIST, Volume 3 (1977). Published by the Anthropology Student Group, Department of Anthropology, University of Nebraska, Lincoln, Nebraska 68588 21 / CLAUDE LEVI-STRAUSS: The Man and His Works by Susan M. Voss 'INTRODUCTION "Claude Levi-Strauss,I Professor of Social Anth- ropology at the College de France, is, by com mon consent, the most distinguished exponent ~f this particular academic trade to be found . ap.ywhere outside the English speaking world ... " (Leach 1970: 7) With this in mind, I am still wondering how I came to be embroiled in an attempt not only to understand the mul t:ifaceted theorizing of Levi-Strauss myself, but to interpret even a portion of this wide inventory to my colleagues. ' There is much (the maj ori ty, perhaps) of Claude Levi-Strauss which eludes me yet. To quote Edmund Leach again, rtThe outstanding characteristic of his writing, whether in French or in English, is that it is difficul tto unders tand; his sociological theories combine bafflingcoinplexity with overwhelm ing erudi tion"., (Leach 1970: 8) . -

Women at Crossroads: Multi- Disciplinary Perspectives’

ISSN 2395-4396 (Online) National Seminar on ‘Women at Crossroads: Multi- disciplinary Perspectives’ Publication Partner: IJARIIE ORGANISE BY: DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH PSGR KRISHNAMMAL COLLEGE FOR WOMEN, PEELAMEDU, COIMBATORE Volume-2, Issue-6, 2017 Vol-2 Issue-6 2017 IJARIIE-ISSN (O)-2395-4396 A Comparative Study of the Role of Women in New Generation Malayalam Films and Serials Jibin Francis Research Scholar Department of English PSG College of Arts and Science, Coimbatore Abstract This 21st century is called the era of technology, which witnesses revolutionary developments in every aspect of life. The life style of the 21st century people is very different; their attitude and culture have changed .This change of viewpoint is visible in every field of life including Film and television. Nowadays there are several realty shows capturing the attention of the people. The electronic media influence the mind of people. Different television programs target different categories of people .For example the cartoon programs target kids; the realty shows target youth. The points of view of the directors and audience are changing in the modern era. In earlier time, women had only a decorative role in the films. Their representation was merely for satisfying the needs of men. The roles of women were always under the norms and rules of the patriarchal society. They were most often presented on the screen as sexual objects .Here women were abused twice, first by the male character in the film and second, by the spectators. But now the scenario is different. The viewpoint of the directors as well as the audience has drastically changed .In this era the directors are courageous enough to make films with women as central characters. -

Hariharan (Director) Ç”Μå½± ĸ²È¡Œ (Ť§Å…¨)

Hariharan (director) 电影 串行 (大全) Vikatakavi https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/vikatakavi-7929410/actors Vellam https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/vellam-18358605/actors Ayalathe Sundari https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/ayalathe-sundari-18209771/actors Themmadi Velappan https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/themmadi-velappan-18394072/actors Sujatha https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/sujatha-18386168/actors Rajayogam https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/rajayogam-18393252/actors College Girl https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/college-girl-61059928/actors Tholkan Enikku Manassilla https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/tholkan-enikku-manassilla-18394208/actors Anguram https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/anguram-18352374/actors Ammini Ammaavan https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/ammini-ammaavan-18209284/actors Kanyaadaanam https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/kanyaadaanam-18386933/actors Bhoomidevi Pushpiniyayi https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/bhoomidevi-pushpiniyayi-18210169/actors Snehathinte Mukhangal https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/snehathinte-mukhangal-18378837/actors Yagaswam https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/yagaswam-19600494/actors Adimakkachavadam https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/adimakkachavadam-18209039/actors Rajahamsam https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/rajahamsam-18393237/actors Mangai Oru Gangai https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/mangai-oru-gangai-64768609/actors Poocha Sanyasi https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/poocha-sanyasi-61060205/actors -

Annual Report 2020

Imen¡ -äv kÀ-Æ-I-emime UNIVERSITY OF CALICUT Accredited by NAAC with ‘A’ Grade UNIVERSITY OF CALICUT Calicut University.P.O Malappuram, Kerala 673 635 Phone: +91 494 2407104 http://www.uoc.ac.in ANNU 2020 AL REPORT 2020 ANNUAL REPORT ANNUAL REPORT 2020 UNIVERSITY OF CALICUT University of Calicut - Annual Report 2020 Editorial Committee: The Vice-Chancellor (Chairman). The Pro-Vice-Chancellor. The Registrar. The Controller of Examinations. The Finance Officer. Dr. Manoharan M. (Member, Syndicate). Sri. K.K. Haneefa (Member, Syndicate). Adv. Tom K. Thomas (Member, Syndicate). The Publication Officer. The Director of Research. Dr. Denoj Sebastian, Director, DoA. Dr. B.S. Harikumaran Thampi, Director, CDC. Dr. Sivadasan P., Director, IQAC. Dr. V.K. Subramanian, Director, SDE. Dr. R.V.M. Divakaran, Head, Dep’t. of Malayalam & Kerala Studies. Dr. K.M. Sherrif, Associate Professor, Dep’t. of English. Dr. Abraham Joseph, Professor, Dep’t. of Chemistry. The Deputy Registrar, Administration. The Deputy Registrar, Pl.D. Branch (Convenor). CUP 2115/21/125 2 University of Calicut - Annual Report 2020 Foreword This Annual Report arrays the achievements of the University during the year 2020. The report presents a brief of the academic activities, events, and achievements of this University’s teaching and research departments and the affiliated colleges. The year 2020 has delivered tough times to the entire academic activities of the University. Despite the spread of the epidemic, the University has made remarkable achievements in various fields. Calicut University has achieved these significant successes in 2020 based on the bedrock evolved by the development work done over the last few years. -

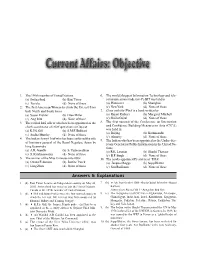

Higher Secondary: SET

RRB PSC Higher Secondary: SET 1. The 190th member of United Nations 6. The world’s biggest Information Technology and tele- (a) Switzerland (b) East Timor communications trade fair-Ce BIT was held in (c) Tuvalu (d) None of these (a) Hannover (b) Shanghai 2. The first American Woman to climb the Everest from (c) New York (d) None of these both North and South faces 7. Gone with the Wind is a book written by (a) Susan Ershler (b) Ellen Miller (a) Rajani Kothari (b) Margaret Mitchell (c) Ang Rita (d) None of these (c) Sheila Gujral (d) None of these 3. The retired IAS officer who has been appointed as the 8. The first summit of the Conference on Interaction chief co-ordinator of relief operations in Gujarat and Confidence Building Measures in Asia (CICA) (a) K.P.S. Gill (b) S.M.F. Bokhari was held in (a) Beijing (b) Kathmandu (c) Sudha Murthy (d) None of these (c) Almatty (d) None of these 4. The Indian Army Chief who has been conferred the title 9. The Indian who has been appointed as the Under-Sec- of honorary general of the Royal Nepalese Army by retary General for Public Information in the United Na- king Gyanendra tions. (a) A.R. Gandhi (b) S. Padmanabhan (a) R.K. Laxman (b) Shashi Tharoor (c) S. Krishnaswamy (d) None of these (c) B.P. Singh (d) None of these 5. The winner of the Miss Universe title 2002 10. The newly appointed President of ‘FIFA’ (a) Oxana Fedorova (b) Justine Pasek (a) Jacques Rogge (b) Sepp Blatter (c) Ling Zhou (d) None of these (c) Sen Ruffianne (d) None of these Answers & Explanations 1. -

Library Catalogue

Id Access No Title Author Category Publisher Year 1 9277 Jawaharlal Nehru. An autobiography J. Nehru Autobiography, Nehru Indraprastha Press 1988 historical, Indian history, reference, Indian 2 587 India from Curzon to Nehru and after Durga Das Rupa & Co. 1977 independence historical, Indian history, reference, Indian 3 605 India from Curzon to Nehru and after Durga Das Rupa & Co. 1977 independence 4 3633 Jawaharlal Nehru. Rebel and Stateman B. R. Nanda Biography, Nehru, Historical Oxford University Press 1995 5 4420 Jawaharlal Nehru. A Communicator and Democratic Leader A. K. Damodaran Biography, Nehru, Historical Radiant Publlishers 1997 Indira Gandhi, 6 711 The Spirit of India. Vol 2 Biography, Nehru, Historical, Gandhi Asia Publishing House 1975 Abhinandan Granth Ministry of Information and 8 454 Builders of Modern India. Gopal Krishna Gokhale T.R. Deogirikar Biography 1964 Broadcasting Ministry of Information and 9 455 Builders of Modern India. Rajendra Prasad Kali Kinkar Data Biography, Prasad 1970 Broadcasting Ministry of Information and 10 456 Builders of Modern India. P.S.Sivaswami Aiyer K. Chandrasekharan Biography, Sivaswami, Aiyer 1969 Broadcasting Ministry of Information and 11 950 Speeches of Presidente V.V. Giri. Vol 2 V.V. Giri poitical, Biography, V.V. Giri, speeches 1977 Broadcasting Ministry of Information and 12 951 Speeches of President Rajendra Prasad Vol. 1 Rajendra Prasad Political, Biography, Rajendra Prasad 1973 Broadcasting Eminent Parliamentarians Monograph Series. 01 - Dr. Ram Manohar 13 2671 Biography, Manohar Lohia Lok Sabha 1990 Lohia Eminent Parliamentarians Monograph Series. 02 - Dr. Lanka 14 2672 Biography, Lanka Sunbdaram Lok Sabha 1990 Sunbdaram Eminent Parliamentarians Monograph Series. 04 - Pandit Nilakantha 15 2674 Biography, Nilakantha Lok Sabha 1990 Das Eminent Parliamentarians Monograph Series. -

Abusive Humour in Malayalam Movies

Annals of R.S.C.B., ISSN:1583-6258, Vol. 25, Issue 4, 2021, Pages.17594 - 17598 Received 29 January 2021; Accepted 04March 2021. Abusive Humour In Malayalam Movies Harikrishnan.P.R 1, R Malavika Kamath 2, Dr. N Sreelakshmi 3 1 Student,MA English, IV Semester, Department of English Language and Literature, Amrita School of Arts and Sciences, Kochi, Amrita Viswa Vidyapeetham, India. 2 Student, MA English, X Semester, Department of English Language and Literature, Amrita School of Arts and Sciences, Kochi, Amrita Viswa Vidyapeetham, India. 3 Assistant Professor, Department of English Language and Literature, Amrita School of Arts and Sciences, Kochi, Amrita Viswa Vidyapeetham, India. ABSTRACT Even in this technologically advanced twenty first century, women are ‘merely women’ for some ‘dark’ minds. They might be unaware of the developments and progress made by women in all walks of life; or sometimes they may be intentionally keeping aloof from knowing the reality. The paper discusses the representation of women in Malayalam film industry. How women are abused particularly to invoke humour– that is the focus point of this paper. Vulgar representations and cheap humours made out of women have to be discussed in detail. Puns and scenes with sexual flavouring are mostly a trend in the ‘New Generation Movies’ released during the decade after 2010. But its precursor decade is not too far away in this respect. Therefore, the paper is trying to analyse the abusive humour produced in Mollywood from the year 2000 upto 2020. Feminist film theory which always criticized the movies for their stereotypical representation deserves special mention here. -

(Life Sciences) 2019-2020

CENTRAL UNIVERSITY OF TAMIL NADU, THIRUVARUR PROVISIONAL RANK LIST FOR Integrated M.Sc. (Life Sciences) 2019-2020 Sl. Total No. RegNo RollNo Candidate's Name Father's Name Gender Cateogry Marks 1 UI10018306 11750042 PRIYANSH CHAUDHARY NILESH CHAUDHARY MALE OBC 80 2 UI10032319 11760134 JAY VERMA PANKAJ VERMA MALE GENERAL 78.75 3 UI10008919 11590139 CHANDANA B NAIR BIJU P S FEMALE GENERAL 76.5 4 UI10017124 11600140 KARAN J GEORGE A J JOY MALE GENERAL 76.25 5 UI10001457 11240010 M M SHRIVIDHATRI M SIVARAMA KRISHNA FEMALE GENERAL 74.25 6 UI10010832 11030010 BHAVESH SUTHAR BHAGIRATH SUTHAR MALE OBC 73.5 7 UI10023562 11600988 JASEELA P SAIDALIKUTTY P FEMALE OBC 73 8 UI10012980 11990220 ASHWIN B NAIR B BIJU MALE GENERAL 73 9 UI10003184 11560116 SREDHA S SUNIL SUNIL S FEMALE OBC 72.75 10 UI10050945 11640223 SHAMIM AKHTAR MOHAMMAD PARVEZ ANWAR MALE GENERAL 72.5 11 UI10024207 11601005 BINSHAD KALLAYI ABDURAHMAN MALE OBC 71.75 12 UI10051129 11740091 RAJA BRINDHA K KRISHNAN FEMALE OBC 71.25 13 UI10058936 11730025 ANJANEYA J S JISHA E T MALE OBC 71.25 14 UI10028261 11780044 SAVIO JOHN AUGUSTINE AUGUSTHY K J MALE GENERAL 71 15 UI10010463 11990029 KARTHIK BINU KARTHIK BINU MALE GENERAL 70.75 16 UI10041232 11601286 ALKA GEORGE GEORGE JOSEPH FEMALE GENERAL 70.75 17 UI10000389 11580003 ANUBHAV JETHI ANUBHAV JETHI MALE GENERAL 70.75 18 UI10040914 11601276 MOHAMED YASEEN ABDU PALLIKKAL MALE OBC 70 19 UI10000928 11590003 ANJALI P K RAMAKRISHNAN M V FEMALE GENERAL 69.25 20 UI10061970 12070248 TRIPTI PANDEY PRADEEP KUMAR PANDEY FEMALE GENERAL 69.25 21 UI10002277 -

Malayalam - Novel

NEW BOMBAY KERALEEYA SAMAJ , LIBRARY LIBRARY LIST MALAYALAM - NOVEL SR.NO: BOOK'S NAME AUTHOR TYPE 4000 ORU SEETHAKOODY A.A.AZIS NOVEL 4001 AADYARATHRI NASHTAPETTAVAR A.D. RAJAN NOVEL 4002 AJYA HUTHI A.N.E. SUVARNAVALLY NOVEL 4003 UPACHAPAM A.N.E. SUVARNAVALLY NOVEL 4004 ABHILASHANGELEE VIDA A.P.I. SADIQ NOVEL 4005 GREEN CARD ABRAHAM THECKEMURY NOVEL 4006 TARSANUM IRUMBU MANUSHYARUM ADGAR RAICE BAROSE NOVEL 4007 TARSANUM KOLLAKKARUM ADGAR RAICE BAROSE NOVEL 4008 PATHIMOONNU PRASNANGAL AGATHA CHRISTIE D.NOVEL 4009 ABC NARAHATHYAKAL AGATHA CHRISTIE D.NOVEL 4010 HARITHABHAKALKK APPURAM AKBAR KAKKATTIL NOVEL 4011 ENMAKAJE AMBIKA SUDAN MANGAD NOVEL 4012 EZHUTHATHA KADALAS AMRITA PRITAM NOVEL 4013 MARANA CERTIFICATE ANAND NOVEL 4014 AALKKOOTTAM ANAND NOVEL 4015 ABHAYARTHIKAL ANAND NOVEL 4016 MARUBHOOMIKAL UNDAKUNNATHU ANAND NOVEL 4017 MANGALAM RAHIM MUGATHALA NOVEL 4018 VARDHAKYAM ENDE DUKHAM ARAVINDAN PERAMANGALAM NOVEL 4019 CHORAKKALAM SIR ARTHAR KONAN DOYLE D.NOVEL 4020 THIRICHU VARAVU ASHTAMOORTHY NOVEL 4021 MALSARAM ASHWATHI NOVEL 4022 OTTAPETTAVARUDEY RATHRI BABU KILIROOR NOVEL 4023 THANAL BALAKRISHNAN NOVEL 4024 NINGAL ARIYUNNATHINE BALAKRISHNAN MANGAD NOVEL 4025 KADAMBARI BANABATTAN NOVEL 4026 ANANDAMADAM BANKIM CHANDRA CHATTERJI NOVEL 4027 MATHILUKAL VIKAM MOHAMMAD BASHEER NOVEL 4028 ATTACK BATTEN BOSE NOVEL 4029 DR.DEVIL BATTON BOSE D.NOVEL 4030 CHANAKYAPURI BATTON BOSE D.NOVEL 4031 RAKTHA RAKSHASSE BRAM STOCKER NOVEL 4032 NASHTAPETTAVARUDEY SANGAGANAM C.GOPINATH NOVEL 4033 PRAKRTHI NIYAMAM C.R.PARAMESHWARAN NOVEL 4034 CHUZHALI C.RADHAKRISHNAN NOVEL 4035 VERUKAL PADARUNNA VAZHIKAL C.RADHAKRISHNAN NOVEL 4036 ATHIRUKAL KADAKKUNNAVAR C.RADHAKRISHNAN NOVEL 4037 SAHADHARMINI C.RADHAKRISHNAN NOVEL 4038 KAANAL THULLIKAL C.RADHAKRISHNAN NOVEL 4039 POOJYAM C.RADHAKRISHNAN NOVEL 4040 KANGALIKAL C.RADHAKRISHNAN NOVEL 4041 THEVADISHI C.RADHAKRISHNAN NOVEL 4042 KANKALIKAL C.RADHAKRISHNAN NOVEL 4043 MRINALAM C.RADHAKRISHNAN NOVEL 4044 KANNIMANGAKAL C.RADHAKRISHNAN NOVEL 4045 MALAKAMAAR CHIRAKU VEESHUMBOL C.V.