Perceptions of Stakeholders Regarding Wilderness and Best Management Practices in an Alaska Recreation Area Emily F

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wilderness in Southeastern Alaska: a History

Wilderness in Southeastern Alaska: A History John Sisk Today, Southeastern Alaska (Southeast) is well known remoteness make it wild in the most definitive sense. as a place of great scenic beauty, abundant wildlife and The Tongass encompasses 109 inventoried roadless fisheries, and coastal wilderness. Vast expanses of areas covering 9.6 million acres (3.9 million hectares), wild, generally undeveloped rainforest and productive and Congress has designated 5.8 million acres (2.3 coastal ecosystems are the foundation of the region’s million hectares) of wilderness in the nation’s largest abundance (Fig 1). To many Southeast Alaskans, (16.8 million acre [6.8 million hectare]) national forest wilderness means undisturbed fish and wildlife habitat, (U.S. Forest Service [USFS] 2003). which in turn translates into food, employment, and The Wilderness Act of 1964 provides a legal business. These wilderness values are realized in definition for wilderness. As an indicator of wild subsistence, sport and commercial fisheries, and many character, the act has ensured the preservation of facets of tourism and outdoor recreation. To Americans federal lands displaying wilderness qualities important more broadly, wilderness takes on a less utilitarian to recreation, science, ecosystem integrity, spiritual value and is often described in terms of its aesthetic or values, opportunities for solitude, and wildlife needs. spiritual significance. Section 2(c) of the Wilderness Act captures the essence of wilderness by identifying specific qualities that make it unique. The provisions suggest wilderness is an area or region characterized by the following conditions (USFS 2002): Section 2(c)(1) …generally appears to have been affected primarily by the forces of nature, with the imprint of man’s work substantially unnoticeable; Section 2(c)(2) …has outstanding opportunities for solitude or a primitive and unconfined type of recreation; Section 2(c)(3) …has at least five thousand acres of land or is of sufficient FIG 1. -

Public Law 96-487 (ANILCA)

APPENDlX - ANILCA 587 94 STAT. 2418 PUBLIC LAW 96-487-DEC. 2, 1980 16 usc 1132 (2) Andreafsky Wilderness of approximately one million note. three hundred thousand acres as generally depicted on a map entitled "Yukon Delta National Wildlife Refuge" dated April 1980; 16 usc 1132 {3) Arctic Wildlife Refuge Wilderness of approximately note. eight million acres as generally depicted on a map entitled "ArcticNational Wildlife Refuge" dated August 1980; (4) 16 usc 1132 Becharof Wilderness of approximately four hundred note. thousand acres as generally depicted on a map entitled "BecharofNational Wildlife Refuge" dated July 1980; 16 usc 1132 (5) Innoko Wilderness of approximately one million two note. hundred and forty thousand acres as generally depicted on a map entitled "Innoko National Wildlife Refuge", dated October 1978; 16 usc 1132 (6} Izembek Wilderness of approximately three hundred note. thousand acres as �enerally depicted on a map entitied 16 usc 1132 "Izembek Wilderness , dated October 1978; note. (7) Kenai Wilderness of approximately one million three hundred and fifty thousand acres as generaJly depicted on a map entitled "KenaiNational Wildlife Refuge", dated October 16 usc 1132 1978; note. (8) Koyukuk Wilderness of approximately four hundred thousand acres as generally depicted on a map entitled "KoxukukNational Wildlife Refuge", dated July 1980; 16 usc 1132 (9) Nunivak Wilderness of approximately six hundred note. thousand acres as generally depicted on a map entitled "Yukon DeltaNational Wildlife Refuge", dated July 1980; 16 usc 1132 {10} Togiak Wilderness of approximately two million two note. hundred and seventy thousand acres as generally depicted on a map entitled "Togiak National Wildlife Refuge", dated July 16 usc 1132 1980; note. -

Chuck River Wilderness Endicott River Wilderness Kootznoowoo

US DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE FOREST SERVICE ALASKA REGION Klukwan Skagway TONGASS NATIONAL FOREST Ò 1:265,000 3 1.5 0 3 6 9 12 Miles 4.5 2.25 0 4.5 9 13.5 18 Kilometers [ Cities Congressionally Designated LUD II Areas and Monument Mainline Roads Wilderness/Monument Wilderness Other Road Canada Roaded Roadless National Park 2001 Roadless Areas National Wildlife Refuge Tongass 77 VCU AK Mental Health Trust Land Exchange Land Returned to NFS Non-Forest Service Land Selected by AK Mental Health Haines Development LUD* Tongass National Forest * Development LUDs include Timber Production, Modified Landscape, Scenic Viewshed, and Experimental Forest Map Disclaimer: The USDA Forest Service makes no warranty, expressed or implied, including the warranties of merchantability and fitness for a particular purpose, nor assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, reliability, completeness or utility of these geospatial data, or for the improper or incorrect use of these geospatial data. These geospatial data and related maps or graphics are not legal documents and are not intended to be used as such. The data and maps may not be used to determine title, ownership, legal descriptions or boundaries, legal jurisdiction, or restrictions that may be in place on either public or private land. Natural hazards may or may not be depicted on the data and maps, and land users should exercise due caution. The data are dynamic and may change over time. The user is responsible to verify the limitations of the geospatial data and to use the data accordingly and use constraints information. Map 2/6 Endicott River Wilderness Gustavus Pleasant/Lemusurier/Inian Islands Wilderness Elfin Cove Pelican Hoonah Juneau West Chichagof-Yakobi Wilderness Tenakee Springs Kootznoowoo Wilderness Angoon Tracy Arm-Fords Terror Wilderness Chuck River Wilderness Sitka Sources: Esri, GEBCO, NOAA, National Geographic, Garmin, HERE, Geonames.org, and other contributors, Esri, Garmin, GEBCO, NOAA NGDC, and other contributors. -

Steve Mccutcheon Collection, B1990.014

REFERENCE CODE: AkAMH REPOSITORY NAME: Anchorage Museum at Rasmuson Center Bob and Evangeline Atwood Alaska Resource Center 625 C Street Anchorage, AK 99501 Phone: 907-929-9235 Fax: 907-929-9233 Email: [email protected] Guide prepared by: Sara Piasecki, Archivist TITLE: Steve McCutcheon Collection COLLECTION NUMBER: B1990.014 OVERVIEW OF THE COLLECTION Dates: circa 1890-1990 Extent: approximately 180 linear feet Language and Scripts: The collection is in English. Name of creator(s): Steve McCutcheon, P.S. Hunt, Sydney Laurence, Lomen Brothers, Don C. Knudsen, Dolores Roguszka, Phyllis Mithassel, Alyeska Pipeline Services Co., Frank Flavin, Jim Cacia, Randy Smith, Don Horter Administrative/Biographical History: Stephen Douglas McCutcheon was born in the small town of Cordova, AK, in 1911, just three years after the first city lots were sold at auction. In 1915, the family relocated to Anchorage, which was then just a tent city thrown up to house workers on the Alaska Railroad. McCutcheon began taking photographs as a young boy, but it wasn’t until he found himself in the small town of Curry, AK, working as a night roundhouse foreman for the railroad that he set out to teach himself the art and science of photography. As a Deputy U.S. Marshall in Valdez in 1940-1941, McCutcheon honed his skills as an evidential photographer; as assistant commissioner in the state’s new Dept. of Labor, McCutcheon documented the cannery industry in Unalaska. From 1942 to 1944, he worked as district manager for the federal Office of Price Administration in Fairbanks, taking photographs of trading stations, communities and residents of northern Alaska; he sent an album of these photos to Washington, D.C., “to show them,” he said, “that things that applied in the South 48 didn’t necessarily apply to Alaska.” 1 1 Emanuel, Richard P. -

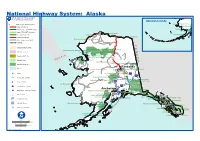

National Highway System: Alaska U.S

National Highway System: Alaska U.S. Department of Transportation Federal Highway Administration Aleutian Islands Eisenhower Interstate System Lake Clark National Preserve Lake Clark Wilderness Other NHS Routes Non-Interstate STRAHNET Route Katmai National Preserve Katmai Wilderness Major STRAHNET Connector Lonely Distant Early Warning Station Intermodal Connector Wainwright Dew Station Aniakchak National Preserve Barter Island Long Range Radar Site Unbuilt NHS Routes Other Roads (not on NHS) Point Lay Distant Early Warning Station Railroad CC Census Urbanized Areas AA Noatak Wilderness Gates of the Arctic National Park Cape Krusenstern National Monument NN Indian Reservation Noatak National Preserve Gates of the Arctic Wilderness Kobuk Valley National Park AA Department of Defense Kobuk Valley Wilderness AA D II Gates of the Arctic National Preserve 65 D SSSS UU A National Forest RR Bering Land Bridge National Preserve A Indian Mountain Research Site Yukon-Charley Rivers National Preserve National Park Service College Fairbanks Water Campion Air Force Station Fairbanks Fortymile Wild And Scenic River Fort Wainwright Fort Greely (Scheduled to close) Airport A2 4 Denali National Park A1 Intercity Bus Terminal Denali National PreserveDenali Wilderness Wrangell-Saint Elias National Park and Preserve Tatalina Long Range Radar Site Wrangell-Saint Elias National Preserve Ferry Terminal A4 Cape Romanzof Long Range Radar Site Truck/Pipeline Terminal A1 Anchorage 4 Wrangell-Saint Elias Wilderness Multipurpose Passenger Facility Sparrevohn Long -

October/November 2017 1 Volume 17 • Issue 9 • October/November 2017 Terry W

October/November 2017 www.FishAlaskaMagazine.com 1 Volume 17 • Issue 9 • October/November 2017 Terry W. Sheely W. Terry © 40 Departments Features Fish Alaska Traveler 6 The Backside of Admiralty Fish Alaska Creel 10 by Terry W. Sheely 40 Fish Alaska Gear Bag 12 Contributing Editor Terry Sheely ventures to the backside of Admiralty Island, exploring the vast Fish Alaska Online 14 eastern shore and finding a plethora of unfished Fishing for a Compliment 16 honey-holes every angler should know about. Fish Alaska Families 18 Spoon-feed ’Em by George Krumm 46 Salmon Sense 20 Hard water and heavy metal are a match made Fish Alaska Conservation 22 in heaven, so enterprising ice anglers should take 34 Fish Alaska Fly 24 heed of this in-depth how-to from Contributing Fish Alaska Boats 26 Editor George Krumm, which takes us through Fish Alaska Saltwater 30 all the ins-and-outs of vertically jigging spoons for lake trout, Arctic char, rainbows and burbot. Fish Alaska Stillwater 32 Fish Alaska Recipe 70 Building a DIY Ice Shelter by Joe Overlock 54 Advertiser Index 73 Having a cozy, comfortable shelter will allow you Final Drift 74 to spend more time on the ice this winter, which ultimately means more fish through the hole. SPECIAL SECTION Here Joe Overlock explains how to build a great shanty on a slim budget. Holiday Gift Guide - Part One 34 Here is a list of items on our wish list this Crossover Flies for Silver Salmon © George Krumm © George 46 season. Make your loved ones’ lives a bit easier by Angelo Peluso 60 by leaving this page opened with your desired Don’t get hemmed in by tradition; try some gift circled. -

Coronation Island Wilderness Kuiu Wilderness Chuck River Wilderness

Chuck River Wilderness Kootznoowoo Wilderness Tracy Arm-Fords Terror Wilderness South Baranof Kake Wilderness Petersburg Creek-Duncan Salt Chuck Wilderness Petersburg Tebenkof Bay Stikine-LeConte Wilderness Wilderness Port Alexander Kuiu Wilderness Point Baker Port Protection Wrangell Coronation Island Whale Pass Wilderness Warren Edna Bay Island Wilderness US DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE FOREST SERVICE ALASKA REGION TONGASS NATIONAL FOREST Ò 1:240,000 4.5 2.25 0 4.5 9 13.5 18 Miles Coffman Cove 7 3.5 0 7 14 21 28 Kilometers Naukati [ Cities Congressionally Designated LUD II Areas and Monument South Etolin Wilderness MVUM Roads Wilderness/Monument Wilderness Roaded Roadless Canada 2001 Roadless Areas National Park Tongass 77 VCU National Wildlife Refuge Maurille AK Mental Health Trust Land Exchange Islands Non-Forest Service Wilderness Land Returned to NFS Development LUD* Misty Fiords National Monument Wilderness Land Selected by AK Mental Health Tongass National Forest * Development LUDs include Timber Production, Modified Landscape, Scenic Viewshed, and Experimental Forest Map Disclaimer: The USDA Forest Service makes no warranty, expressed or implied, including the warranties of merchantability and fitness for a particular purpose, nor assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, reliability, completeness or utility of these geospatial data, or for the improper or incorrect use of these geospatial data. These geospatial data and related maps or graphics are not legal documents and are not intended to be used as such. The data and maps may not be used to determine title, ownership, legal descriptions or boundaries, legal jurisdiction, or restrictions that may be in place on either public or private land. -

Table 7 - National Wilderness Areas by State

Table 7 - National Wilderness Areas by State * Unit is in two or more States ** Acres estimated pending final boundary determination + Special Area that is part of a proclaimed National Forest State National Wilderness Area NFS Other Total Unit Name Acreage Acreage Acreage Alabama Cheaha Wilderness Talladega National Forest 7,400 0 7,400 Dugger Mountain Wilderness** Talladega National Forest 9,048 0 9,048 Sipsey Wilderness William B. Bankhead National Forest 25,770 83 25,853 Alabama Totals 42,218 83 42,301 Alaska Chuck River Wilderness 74,876 520 75,396 Coronation Island Wilderness Tongass National Forest 19,118 0 19,118 Endicott River Wilderness Tongass National Forest 98,396 0 98,396 Karta River Wilderness Tongass National Forest 39,917 7 39,924 Kootznoowoo Wilderness Tongass National Forest 979,079 21,741 1,000,820 FS-administered, outside NFS bdy 0 654 654 Kuiu Wilderness Tongass National Forest 60,183 15 60,198 Maurille Islands Wilderness Tongass National Forest 4,814 0 4,814 Misty Fiords National Monument Wilderness Tongass National Forest 2,144,010 235 2,144,245 FS-administered, outside NFS bdy 0 15 15 Petersburg Creek-Duncan Salt Chuck Wilderness Tongass National Forest 46,758 0 46,758 Pleasant/Lemusurier/Inian Islands Wilderness Tongass National Forest 23,083 41 23,124 FS-administered, outside NFS bdy 0 15 15 Russell Fjord Wilderness Tongass National Forest 348,626 63 348,689 South Baranof Wilderness Tongass National Forest 315,833 0 315,833 South Etolin Wilderness Tongass National Forest 82,593 834 83,427 Refresh Date: 10/14/2017 -

Elegant Ms Zuiderdam

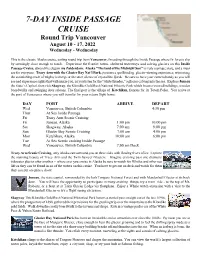

7-DAY INSIDE PASSAGE CRUISE Round Trip Vancouver August 10 - 17, 2022 Wednesday - Wednesday This is the classic Alaska cruise, sailing round trip from Vancouver, threading through the Inside Passage where fir forests slip by seemingly close enough to touch. Experience the frontier towns, sheltered waterways and calving glaciers on this Inside Passage Cruise, aboard the elegant ms Zuiderdam. Alaska “The land of the Midnight Sun” is truly a unique state, and a must see for everyone. Tracy Arm with the Glacier Bay Nat’l Park, presents a spellbinding glacier-viewing experience, witnessing the astonishing crash of mighty icebergs or the utter silence of crystalline fjords. Be sure to have your camera handy as you will see and experience sights that will amaze you, as you listen for the “white thunder,” a glacier calving into the sea. Explore Juneau the State’s Capital, then visit Skagway, the Klondike Gold Rush National Historic Park which boasts restored buildings, wooden boardwalks and swinging door saloons. The final port is the village of Ketchikan, famous for its Totem Poles. You arrive at the port of Vancouver where you will transfer for your return flight home. DAY PORT ARRIVE DEPART Wed Vancouver, British Columbia 4:30 pm Thur At Sea Inside Passage Fri Tracy Arm Scenic Cruising Fri Juneau, Alaska 1:00 pm 10:00 pm Sat Skagway, Alaska 7:00 am 9:00 pm Sun Glacier Bay Scenic Cruising 7:00 am 4:00 pm Mon Ketchikan, Alaska 10:00 am 6:00 pm Tue At Sea Scenic cruising Inside Passage Wed Vancouver, British Columbia 7:00 am Dock Tracy Arm Scenic Cruising, only Alaska can surround you on three sides with flowing rivers of ice. -

Alaskan Dream Cruises 2021

2021 Alaskan Dream Cruises Search for humpback whales, orcas, coastal brown bears, Learn from knowledgeable captains, naturalists, mountain goats and more as we venture through the cultural heritage guides and crew. Enjoy educational region’s most abundant wildlife areas. enrichment programs throughout the voyage. Experience Alaskan culture in remote Native villages and Dynamic itineraries, including the all-new “North To charming towns – from the state capital to rural fishing True Alaska” expedition—designed by the Allen family communities. in celebration of Alaskan Dream Cruises’ 10 year Explore stunning glacial fjords, including Glacier Bay anniversary National Park and Preserve and the Tracy-Arm Ford’s Terror Wilderness Area. Call 800-977-9705 Savor Alaska’s unparalleled serenity at our exclusive Orca Alaska Cruises & Vacations by Tyee Travel Point Lodge on the shores of Colt Island, with king crab and a beach bonfire for s’mores. Celebrating 10 Years of True Alaska with True Alaskans 7-night, Last Frontier Adventure Day 1 Sitka: Explore beautiful Sitka, the only community in Southeast Alaska that faces the open ocean waters of the Gulf of Alaska. Participate in a wilderness hike on one of the many trails in town. Visit sites that highlight the community’s rich Alaska Native and Russian history. Embark for the winding narrows north of town while searching for bald eagles, sea otters, bears, whales, and other wildlife. Day 2 Rainforest Hike & Baranof Island's Waterfall Coast: Spend the day exploring remote, Inside Passage wilderness. Hike a rainforest trail featuring towering spruce and hemlock trees and lush undergrowth. Your knowledgeable guide will provide commentary on the indigenous plants and wildlife of the area. -

Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act

APPENDIX - ANILCA 537 XXIII. APPENDIX 1. Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act PUBLIC LAW 96–487—DEC. 2, 1980 94 STAT. 2371 Public Law 96–487 96th Congress An Act To provide for the designation and conservation of certain public lands in the State Dec. 2, 1980 of Alaska, including the designation of units of the National Park, National [H.R. 39] Wildlife Refuge, National Forest, National Wild and Scenic Rivers, and National Wilderness Preservation Systems, and for other purposes. Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, Alaska National SECTION 1. This Act may be cited as the “Alaska National Interest Lands Interest Lands Conservation Act”. Conservation Act. TABLE OF CONTENTS 16 USC 3101 note. TITLE I—PURPOSES, DEFINITIONS, AND MAPS Sec. 101. Purposes. Sec. 102. Definitions. Sec. 103. Maps. TITLE II—NATIONAL PARK SYSTEM Sec. 201. Establishment of new areas. Sec. 202. Additions to existing areas. Sec. 203. General administration. Sec. 204. Native selections. Sec. 205. Commercial fishing. Sec. 206. Withdrawal from mining. TITLE III—NATIONAL WILDLIFE REFUGE SYSTEM Sec. 301. Definitions. Sec. 302. Establishment of new refuges. Sec. 303. Additions to existing refuges. Sec. 304. Administration of refuges. Sec. 305. Prior authorities. Sec. 306. Special study. TITLE IV—NATIONAL CONSERVATION AREA AND NATIONAL RECREATION AREA Sec. 401. Establishment of Steese National Conservation Area. Sec. 402. Administrative provisions. Sec. 403. Establishment of White Mountains National Recreation Area. Sec. 404. Rights of holders of unperfected mining claims. TITLE V—NATIONAL FOREST SYSTEM Sec. 501. Additions to existing national forests. -

Coastal Habitat Mapping Program

Coastal Habitat Mapping Program Southeast Alaska Data Summary Report ShoreZone October 2011 Prepared for: The Nature Conservancy On the Cover: South Coronation Island Sawyer Glacier, Tracy Arm North Zarembo Island Juneau, AK CORI Project: 10-17 Oct 2011 ShoreZone Coastal Habitat Mapping Data Summary Report 2004-2010 Survey Area, Southeast Alaska Prepared for: NOAA National Marine Fisheries Service, Alaska Region The Nature Conservancy Prepared by: COASTAL & OCEAN RESOURCES INC ARCHIPELAGO MARINE RESEARCH LTD 759A Vanalman Ave., Victoria BC V8Z 3B8 Canada 525 Head Street, Victoria BC V9A 5S1 Canada (250) 658-4050 (250) 383-4535 www.coastalandoceans.com www.archipelago.ca October 2011 SE Alaska Summary (TNC) 2 SUMMARY ShoreZone is a coastal habitat mapping and classification system in which georeferenced aerial imagery is collected specifically for the interpretation and integration of geological and biological features of the intertidal zone and nearshore environment. The mapping methodology is summarized in Harney et al (2008). This interim data summary report provides information on geomorphic and biological features of 28,595 km of shoreline mapped in 2004-2010 surveys of Southeast Alaska. There is approximately 1,100 km of unmapped shoreline in Glacier Bay. The habitat inventory is comprised of 88,704 along-shore segments (units), averaging 322 m in length. Organic shorelines (such as estuaries) are mapped along 3,388 km (12%) of the study area. Bedrock shorelines (BC Classes 1-5) comprise 4,947 km (17%) of mapped shorelines. Of these, steep rock cliffs are the most common mapped along 3,682 km (13%) of the shoreline. A little less than half of the mapped coastal environment is characterized as combinations of rock and sediment shorelines (BC Classes 6-20): 11,747 km (41%).