Islam Practices of Traders

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

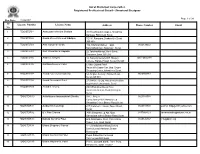

Section 124- Unpaid and Unclaimed Dividend

Sr No First Name Middle Name Last Name Address Pincode Folio Amount 1 ASHOK KUMAR GOLCHHA 305 ASHOKA CHAMBERS ADARSHNAGAR HYDERABAD 500063 0000000000B9A0011390 36.00 2 ADAMALI ABDULLABHOY 20, SUKEAS LANE, 3RD FLOOR, KOLKATA 700001 0000000000B9A0050954 150.00 3 AMAR MANOHAR MOTIWALA DR MOTIWALA'S CLINIC, SUNDARAM BUILDING VIKRAM SARABHAI MARG, OPP POLYTECHNIC AHMEDABAD 380015 0000000000B9A0102113 12.00 4 AMRATLAL BHAGWANDAS GANDHI 14 GULABPARK NEAR BASANT CINEMA CHEMBUR 400074 0000000000B9A0102806 30.00 5 ARVIND KUMAR DESAI H NO 2-1-563/2 NALLAKUNTA HYDERABAD 500044 0000000000B9A0106500 30.00 6 BIBISHAB S PATHAN 1005 DENA TOWER OPP ADUJAN PATIYA SURAT 395009 0000000000B9B0007570 144.00 7 BEENA DAVE 703 KRISHNA APT NEXT TO POISAR DEPOT OPP OUR LADY REMEDY SCHOOL S V ROAD, KANDIVILI (W) MUMBAI 400067 0000000000B9B0009430 30.00 8 BABULAL S LADHANI 9 ABDUL REHMAN STREET 3RD FLOOR ROOM NO 62 YUSUF BUILDING MUMBAI 400003 0000000000B9B0100587 30.00 9 BHAGWANDAS Z BAPHNA MAIN ROAD DAHANU DIST THANA W RLY MAHARASHTRA 401601 0000000000B9B0102431 48.00 10 BHARAT MOHANLAL VADALIA MAHADEVIA ROAD MANAVADAR GUJARAT 362630 0000000000B9B0103101 60.00 11 BHARATBHAI R PATEL 45 KRISHNA PARK SOC JASODA NAGAR RD NR GAUR NO KUVO PO GIDC VATVA AHMEDABAD 382445 0000000000B9B0103233 48.00 12 BHARATI PRAKASH HINDUJA 505 A NEEL KANTH 98 MARINE DRIVE P O BOX NO 2397 MUMBAI 400002 0000000000B9B0103411 60.00 13 BHASKAR SUBRAMANY FLAT NO 7 3RD FLOOR 41 SEA LAND CO OP HSG SOCIETY OPP HOTEL PRESIDENT CUFFE PARADE MUMBAI 400005 0000000000B9B0103985 96.00 14 BHASKER CHAMPAKLAL -

Manubarwala Haji Daud Munshi Memorial Hostel, Gulistan Nagar, Juna Jin Road, Rander, Surat – 395005 Tel No

Trust Reg. No. : E-2343 SURAT Manubarwala Haji Daud Munshi Memorial Hostel, Gulistan Nagar, Juna Jin Road, Rander, Surat – 395005 Tel No. : 91-261-2762685 Web. : www.pmet.org Introductions & Activities Comprehensive Adoption Scheme For Bright Students C.A. Total Adoption Programme Medical Help Scholarship For Higher Education Deeni Education Prize Distribution Civil Services Exams Elocution Competition Educational & Vocational Guidance Primary Talent Search Project Computer Education Hostel Facility Care Programme Dear Patrons and Readers: Assalamu Alaykum w.w. It is our utmost pleasure to inform you that the current year 2014 marks the 28th Anniversary of PMET's efforts to minimize backwardness of Muslims in Gujarat in the field of education. PMET was established with a view to considering education is the only solution of myriad problems Muslims face. Alhamdulillah, efforts were paid back and as a result, a considerable awareness and importance of education arose in the community. Now we see a difference. Graduates, post graduates, doctors, engineers and percentage of female education has increased. Though, there is much more to be done as Sachar Commission Report shows. During past 28 years, PMET helped several thousand boys and girls under total and partial adoption schemes to finish their education. Hifzurrehman A. Patel, President, PMET SCHOLARSHIP Under adoption scheme of our trust, students belonging to poor economic background and wishing to complete Degree, Diploma and Post-graduation courses, are given financial assistance so that they can pursue their educational aspirations. We are happy to inform you that 3460 number of students took the advantage of this scheme and earned their degrees in different fields of education. -

State District Branch Address Centre Ifsc Contact1 Contact2 Contact3 Micr Code Amroli V.V Mandli Tal.Choryasi,Sura 0261- Gujarat Surat Amroli Br

STATE DISTRICT BRANCH ADDRESS CENTRE IFSC CONTACT1 CONTACT2 CONTACT3 MICR_CODE AMROLI V.V MANDLI TAL.CHORYASI,SURA 0261- GUJARAT SURAT AMROLI BR. T-394107 AMROLI SDCB0000040 2499835 395244018 TAL.MAHUVA,SURAT- 02625- GUJARAT SURAT ANAVAL BR. 396510 ANAVAL SDCB0000020 252221 33,34 ASHRWAD TOWNSHIP,BAMROLI ROAD,UDHANA BAMROLI,SURAT- 0261- GUJARAT SURAT BAMROLI BR. 394210 SURAT SDCB0000063 2611222 395244029 SARDAR BARDOLI CITY CHOWK,TAL.BARDOL 02622- GUJARAT SURAT BR. I,SURAT-394160 BARDOLI SDCB0000002 220030 STATION BARDOLI ROAD,TAL.BARDOLI, 02622- GUJARAT SURAT STATION BR. SURAT-395003 BARDOLI SDCB0000012 225143 MAHUWA SUGAR FACORY TAL.MAHUVA,SURAT- 02625- GUJARAT SURAT BHAMANIYA BR. 394246 MAHUVA SDCB0000035 256849 NR.CHAITANIY APT.BHATAR ROAD,TAL.CHORYAS 0261- GUJARAT SURAT BHATAR BR. I,SURAT-395001 SURAT SDCB0000039 2241108 395244012 TAL.MANDVI,SURAT- 02623- GUJARAT SURAT BHAUDHAN BR. 394140 BAUDHAN SDCB0000051 251251 CHALTHAN SUGAR FACTORY COMPOUND,TAL.PAL 02622- GUJARAT SURAT CHALTHAN BR. SANA,SURAT-394305 CHALTHAN SDCB0000016 281080 395244020 KANJIBHAI DESAI CHOWK BAZAR BHAVAN,TAL.CHORY 0261- GUJARAT SURAT BR. ASI,SURAT-395003 SURAT SDCB0000024 2599070 395244005 CONTROL CENTRE CONTROL RTGS DEPT., MAIN CENTRE RTGS BRANCH, KANPITH, 0261- 0261- GUJARAT SURAT DEPT. CHUTAPOOL, SURAT SURAT SDCB0000001 2597730 0261-2594739 2597738 DOLVAN CHAR TAL.VYARA,SURAT- 02626- GUJARAT SURAT RASTA BR. 394635 DOLVAN SDCB0000028 251221 GANGADHARA TAL.PALSANA,SURAT- GANGADHR 02622- GUJARAT SURAT BR. 394310 A SDCB0000032 263224 MAZDA GHODOD ROAD APT.TAL.CHORYASI, 0261- GUJARAT SURAT BR. SURAT-395001 SURAT SDCB0000041 2653477 395244014 GHEE KANTA ROAD,TAL.CHORAYS 0261- GUJARAT SURAT HARIPURA BR. I,SURAT-395003 SURAT SDCB0000038 2423472 395244011 MAHAVIR CHOWK,TAL.CHORY 0261- GUJARAT SURAT J.P ROAD BR. -

District Census Handbook, Surat, Part X-C-II, Series-5

PART X-C-Il CENSUS 1971 ( wjtll off PriDts of Part X-C-J) ANALYTICAL REPORT ON CENSUS AND RELATED· STATISTICS ,SOCIO-ECONOMIC SERIES-5 & GUJARAT CULTURAL TABLES ( RURAL AREAS) AND HOUSING TABLES DISTRICT SURAT CENSUS DISTRICT HANDBOOK C. C. DOCTOR of the Indian Administrative Service Director of Census Operations ,Gujarat CENSUS 0' INDIA, 1971 LIST OF PUBUCATIONS Census of India 1971-Series-S-Gujarat is being published in the following parts: Ceotral Govemmeot Publicatioos Part Subject covered Numbel I-A General Report I-B Detailed Analysis of the Demographic, Social, Cultulal and Migration Patterns I-C Subsidiary Tables II-A General P<'pula tion Tables ('A' Series) JI-B Economic Tables ( 'B' Series) , lI-C (i) Distribu:ion of Pupulatiol1; Mother: Tongue and Religion, Scheduled Castes & Scheduled Tribes U-C (ii) Other Social & Cultural Tables and Fertility Tables, Tables on Household Com position, Single Year Age, Marital Status, Educational Levels, Scheduled Castes. & Scheduled Tribes, etc., Bilingualism III Establishments Report and Tables ('E' Series) IV-A Housing Report and Housing Subsidiary Tables IV-B Housing Tables V Special Tables and Ethnographic Notes on Scheduled Castes & Scheduled Tribes VI-A Town Directory VI-B Special Survey Report on Selected Towns VI-C Survey Report on Selected Villages VII Special Report on Graduate and Technical Per~~el: ~ VIII-A Administration Report-Enumeration \~ - For offici~t use onl~;:l VIII-B Administration Report-Tabulation } IX Census Atlas Stale Govel'llllleat Publications DISTRIcr CENSUS HANDBOOK X-A Town and Village Directory X-B Village and Townwise Primary Census Abstract X-C-I Departmental Statistics and Full Count Census Tablf's X-C-II Analytical Report on Census and Related Statistics, Socio Economic and Cultural Tables (Rural Areas), and Housing Tables X-C-II (Supplement) Urban Sample Tablea CONTENTS PAGBS PRI1FACB i-if I. -

SACHIN GIDC BRANCH Plot No

SACHIN GIDC BRANCH Plot No. 1084, Road No. 6, Sachin GIDC, Surat, Gujarat - 394230 BY REGD POST & COURIER To: Mr. PremPrakash Jagannathbhai Ravi Mrs. Indudevi Jagannathbhai Mr. Narendra Pursottamdas (Borrower) Ravi (Co-Borrower) Jena (Guarantor) B-414, Millenium Park Society, B-414, Millenium Park Society, H/2, Pavitra Residency, Opp. Dindoli, Surat. Dindoli, Surat. Bhagyalaxmi Society, Ram Also at Also at Nagar, Rander Road, Surat. Flat 227, Raj Abhishek City Homes, Flat 227, Raj Abhishek City Building No. D-7, Pardi Kande, Homes, Building No. D-7, Pardi Sachin, Surat. Kande, Sachin, Surat. Dear Sir/Madam, SUB: NOTICE OF 30 DAYS FOR SALE OF IMMOVABLE SECURED ASSETS UNDER RULE 8 OF THE SECURITY INTEREST (ENFORCEMENT) RULES, 2002. 1. Union Bank of India, Sachin GIDC Branch, Plot No 1084, Sachin GIDC, Surat, Gujarat -394230, the secured creditor, caused a demand notice dated 10.06.2019 under Section 13(2) of the Securitization and Reconstruction of Financial Assets and Enforcement of Security Interest Act 2002, calling upon you to pay the dues within the time stipulated therein. Since you failed to comply with the said notice within the period stipulated, the Authorized Officer, has taken possession of the immovable secured assets under Section 13(4) of the Act read with Rule 8 of Security Interest (Enforcement) Rules, 2002. Possession notice dated 29.12.2020 issued by the Authorized Officer, as per Appendix IV to the Security Interest (Enforcement) Rules, 2002 was delivered to you and the same was also affixed to the properties mortgaged with the Secured Creditor, apart from publication of the same in newspapers. -

Structural Designers

Surat Municipal Corporation Registered Proffesional Detail - Structural Designer Page 1 of 38 Run Date : 22/06/2021 Sr License Number License Name Address Phone Number Email No. 1 TDO/STDR/1 Amar pravinchandra Shethna 3rd floor,Maruti Complex, Nr.Udhna Darwaja, Ring road, Surat. 2 TDO/STDR/2 Amala Ahmed Mohmed Siddique. 7/2181,Rampura,Chadda Ole,Surat 395 003 3 TDO/STDR/3 Amit Kunjbihari Shah. 104, Krishna Market, Opp. 9825139552 Balanathashram, Katargam, Surat. 4 TDO/STDR/4 Amit Virendrabhai Kapadia. 22,Takshashila apt.Vanki Bordi, Shahpore,Surat.395 003 5 TDO/STDR/5 Anant U. Sanghvi. 12, Navyug Society,B/H Navyug 0261-2684788 College, Rander Road, Surat-395 009 6 TDO/STDR/6 Anil Narottambhai Patel. 6,Uttar Gujarat Patel Nagar,B/h.Sarjan Soc.Opp. Srgam Shopping Center,Athwalines Surat. 7 TDO/STDR/7 Arvind Fakirchand Contrctor. 52, Sngam Society, Rander Road, 9825555361 Surat.395 009 8 TDO/STDR/8 Arvind Govindbhai Patel. 27./544,M.I.G.Guj.Hou.Board,Nr,Bom bay Market ,Umarwada ,Surat 9 TDO/STDR/9 Arvind K. Dharia. 29/A,Bhulabhai Desai Park, laxmikant Asaram Road,Katargam Surat. 10 TDO/STDR/10 AshishkumarJagganathsinh Sisodia. Shree Project 9825169774 Consultancy,43/A,Mangaldeep Shopping Center,Bhatar Road,Surat. 11 TDO/STDR/11 Avdhut Bhimrao Bilgi. 217,Commerce House,Tower Road, 9825181808 [email protected] Surat 12 TDO/STDR/12 B.V.Ram Sharma. 3006,Swapnadeep Apt. Opp. 9377664321 [email protected] Sarvodaya school,Bhatar Road,Surat. 13 TDO/STDR/13 Babulal Kanjibhai Patel. O/9, Mazzanine Floor, Panchratna 9825120167 [email protected] Tower, L.H. -

Surat Municipal Corporation

Surat Municipal Corporation 1 Category of Initiative : “Technical Innovation” Title of the Initiative : “Leakage Mapping and its’ Positive Impact” Presentation by : Jatin Shah, City Engineer, SMC Location: Surat City TO KATHOR Surat City Variav TO AHMEDABAD Kosad TO OLPAD Mota TO KATHOR G.H.B 3 Varachha Kosad E G.H.B V I G.H.B R Jahangirpura I Chhapra P Bhatha TO HAZIRA 28 A T TO KAMREJ Ved TO DANDI Pisad Amroli Sarthana GAMTAL G.E.B. Power House GAMTAL Utran E 53 V Utran 69 I Dabholi Katargam R I Nanavarachha G.I.D.C. P 76 K a t a r g a m A Jahangirabad T 30 51 NORTH ZONE31 29 Rander Singanpor 129 71 70 D.T.P.S. NO - 20 D.T.P.S. NO - 20 (Nana V arach ha-Kapadra) 50 WEIR CUM CAUSE WAY T.P.S.NO.18 (Katargam) T.P.S.-15 Simada TO BHESAN (Fulpada) T.P.S.NO.1 4 T.P.S.NO.3 (Rander Adajan) (Katargam) Fulpada T.P.S. NO 16 59 T.P.S.NO.4 D.T.P.S.NO.17 (Kapa dra ) Ashwanikumar Navagam (Fulpada) Palanpor Tunki D.T .P.S. NO.24 19 D.T.P.S. NO.23 T.P.S.NO.13 45 (Rander) (Adajan) T.P.S.NO .1 (Lal Darwa ja)) 172 T.P.S.NO.11 7 72 (Adajan) EAST ZONE 33 T.P.S.NO.3 1 (Karanj) WEST ZONE 12 62 Puna 14 35 18 57 EXIST.NEHRU BRIDGE T.P.S.NO.12 13 (Adajan) 41 40 SWAMI VIVEKANAND BRIDGE 61 37 60 T.P.S.NO.8 10 (Umarwada ) Magob LOW LEVEL BRIDGE 15 11 TO HAZIRA 77 Adajan 75 21 43 34 17 T.P.S. -

Suitability Analysis of Residential Location Choice Behavior for West Zone in Surat City Yash Jariwala1

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN: 2395-0056 Volume: 08 Issue: 04 | Apr 2021 www.irjet.net p-ISSN: 2395-0072 Suitability Analysis of Residential Location Choice Behavior for West Zone in Surat City Yash Jariwala1 1Student, Master of Town and Country Planning, Sarvajanik College of Engineering and Technology, Surat ---------------------------------------------------------------------***---------------------------------------------------------------------- Abstract - Urban growth inevitably decreases the sustainability of land use and the ecosystem. Thus, in any metropolitan territory, the residential location is a fundamental piece of urban planning. Residential location choice of households is core agents in the urban dynamic system. Determination of Residential area is an exceptionally intricate nature of every household of an urban area. Studies of residential location choice show that many factors contribute to the choice of a given location likes the characteristics of the housing unit, its location with respect to social and environmental amenities as well as access to jobs, services and other economic opportunities. Area decision change with city to city contingent upon above expressed variables and city qualities. This study aims to analyses the residential choice behavior of residents of west zone of Surat city. A questionnaire is designed considering various factors like environment, infrastructure facilities, cost, amenities, and work place location. Initially a pilot survey was conducted to finalize the revised draft of questionnaire. The residents were divided in various income groups. The study area is a quickly developing neighbourhood on the west side of the city. The land prices are also soaring, indicating its attraction attributes. For analysis of location choice Ranking and Weightage approach of multi criteria decision making is used. -

Creditable Initiative of Our Young Brothers Réunionnais

Creditable initiative of our young brothers réunionnais It is with an immense pleasure and much of emotions that I read the report of Reza Issack on the sociocultural demonstration held Sunday August 29, 2004 with Between Two, Ile of the Meeting, under the aegis of the Moslem Philanthropic association of Kathor [ APMK ]. It is with joy which one notes that young people, following the example Isma ël Hassim Locate, seeks to make revive the history of their ancestors, to make known their place, their village, in Large Peninsule. Ismaël Hassim Locate (of which the late father, Hassim Motha, was very expensive to me) was made a duty carry out a kind of pilgrimage in Kathor, village of its aïeux. It was in 1975. It achieved what it always wished. From there, it was interested of advantage in the AMPK, founded in 1954, of which one of the founders is Mr. Aboo Bakar Omarjee, today with the retirement with St Pierre. Among the founder members with the Meeting, fire Ismaël Zadvat, great personality réunionnaise, and Ismaël Molla, inter alia. I was moved by this account by Ismaël Locate which revives me a stay that I carried out in India in company of M.M Mahmad Amine Timol, the mutawalli of Masjid Markaz-E-Islam, and Baboo Randeree, both originating in Kathor. It was in November 1996. We were royally accomodated by the members of the Committee of Reception who are also the administrators of The Kathor Medical Trust, of which MISTERS Usman Umarjee, Ismaël Shaik, Professor Khalik Amla, Ahmed Randeree, Ayub Harif and Yacub Dadubhai, inter alia. -

Surat MO.Pdf

Staff Detail District : ƘƟƑƅ Taluka : ---Select-NA--- PHC : SubCenter : Village : Sr No. Name Phone No Designation District/Taluka/PHC/SubCen tre/Village/PPU/UHC 1 Dr.P.Y.Shah(Surat) 9727709506 EMO (Epidemic Medical SURAT////// Officer) 2 Dr. Bhavin 9724345110 MO (CHC) SURAT/Bardoli/////CHC Bardoli - T 3 Dr.Bhavesh 9824043920 MO (CHC) SURAT/Bardoli/////CHC Bardoli - T 4 DR.BHAVIN B.MAHETA 7567873609 MO (CHC) SURAT/Olpad/////CHC SAYAN Sayan - T 5 Dr.Bhavin H. Modi 9724345110 MO (CHC) SURAT/Chorasi/////CHC Kharvasa 6 Dr.krunal 7567873630 MO (CHC) SURAT/Bardoli/////CHC Bardoli - T 7 Dr.Krunal P. Jariwala 7567873630 MO (CHC) SURAT/Chorasi/////CHC Kharvasa 8 Dr.Ruchi Patel 9429620066 MO (CHC) SURAT/Olpad/////CHC Olpad - T 9 Dr.Ruchir 9662522987 MO (CHC) SURAT/Bardoli/////CHC Bardoli - T 10 Dr.Sejal Surti 8866220903 MO (CHC) SURAT/Olpad/////CHC Olpad - T 11 DR.SHASHIBHUSANKUMAR 7567873608 MO (CHC) SURAT/Olpad/////CHC Sayan - T 12 DR.SHIRISH VADADORIYA 9510981793 MO (CHC) SURAT/Olpad/////CHC SAYAN Sayan - T 13 SURAT-KAMREJ-CHC 7567873627 MO (CHC) SURAT/Kamrej/////CHC KAMREJ-DR. KETAN Kamrej - T M.SOLANKI 14 SURAT-KAMREJ-CHC 9725006759 MO (CHC) SURAT/Kamrej/////CHC KAMREJ-DR. PARESH S. Kamrej - T TAILOR 15 SURAT-MAHUVA-ANAVAL 7567873605 MO (CHC) SURAT/Mahuva/////CHC M.O. DR.JITENDRA N.PATEL Anaval-T 16 SURAT-MAHUVA-ANAVAL 7567873605 MO (CHC) SURAT/Mahuva/////CHC M.O. DR.JITENDRA N.PATEL Anaval-T 17 SURAT-MAHUVA-ANAVAL 7567873605 MO (CHC) SURAT/Mahuva/////CHC M.O. DR.JITENDRA N.PATEL Anaval-T 18 SURAT-MAHUVA-ANAVAL 7567873605 MO (CHC) SURAT/Mahuva/////CHC M.O. -

Muslim Portraits: the Anti-Apartheid Struggle

Muslim Portraits: The Anti-Apartheid Struggle Goolam Vahed Compiled for SAMNET Madiba Publishers 2012 Copyright © SAMNET 2012 Published by Madiba Publishers University of KwaZulu Natal [Howard College] King George V Avenue, Durban, 4001 No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system, without written permission from the publisher. First Edition, First Printing 2012 Printed and bound by: Impress Printers 150 Intersite Avenue, Umgeni Business Park, Durban, South Africa ISBN: 1-874945-25-X Graphic Design by: NT Design 76 Clark Road, Glenwood, Durban, 4001 Contents Foreword 9 Yusuf Dadoo 83 Faried Ahmed Adams 17 Ayesha Dawood 89 Feroza Adams 19 Amina Desai 92 Ameen Akhalwaya 21 Barney Desai 97 Yusuf Akhalwaya 23 AKM Docrat 100 Cassim Amra 24 Cassim Docrat 106 Abdul Kader Asmal 30 Jessie Duarte 108 Mohamed Asmal 34 Ebrahim Ismail Ebrahim 109 Abu Baker Asvat 35 Gora Ebrahim 113 Zainab Asvat 40 Farid Esack 116 Saleem Badat 42 Suliman Esakjee 119 Omar Badsha 43 Karrim Essack 121 Cassim Bassa 47 Omar Essack 124 Ahmed Bhoola 49 Alie Fataar 126 Mphutlane Wa Bofelo 50 Cissie Gool 128 Amina Cachalia 51 Goolam Gool 131 Azhar Cachalia 54 Halima Gool 133 Firoz Cachalia 57 Jainub Gool 135 Moulvi Cachalia 58 Hoosen Haffejee 137 Yusuf Cachalia 60 Fatima Hajaig 140 Ameen Cajee 63 Imam Haron 142 Yunus Carrim 66 Enver Hassim 145 Achmat Cassiem 68 Kader Hassim 148 Fatima Chohan 71 Nina -

City Resilience Study City Resilience Study Challenges and Opportunities for Surat City Contents

CITY RESILIENCE STUDY CITY RESILIENCE STUDY CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES FOR SURAT CITY CONTENTS Approach and List of Partners 2 Preface from Surat Municipality 3 Preface by Shell and Veolia 4 Executive Summary 5 Introduction to City Resilience Study 7 Surat City Characteristics 8 Challenges 11 Opportunities 24 Conclusions and Next Steps 59 CITY RESILIENCE STUDY APPROACH AND LIST OF PARTNERS PREFACE FROM SURAT MUNICIPALITY This study has been co-created together with key stakeholders and municipal leaders in Surat. The approach to this study has been to sees the future, a set of meetings was held with Surat city has embarked on a mission to take I am sure the city of Surat, its enlightened citizenry 3 engage and collaborate, with the objective key stakeholders in the city such as the Surat pre-emptive adaptation measures to mitigate and stakeholders will be able to offset the adverse of understanding the infrastructure challenges Municipal Corporation (SMC), the South Gujarat the impacts of processes associated with climate impacts of climate change on energy through and opportunities the city faces as a result of Chamber of Commerce and Industry (SGCCI), change and variability at the city level. The convergence of approach and synergies of action. urbanisation and identifying innovative and TARU, local business leaders and Torrent Power. process of building resilience to the impacts of Surat has already displayed its inherent resilience credible solutions. To understand how Surat climate change is being spearheaded by the by overcoming the scourge of plague to become Surat Municipal Corporation (SMC) with support the cleanest city in India as also by recovering from WE ARE GRATEFUL TO ALL OUR PARTNERS IN THIS STUDY, ESPECIALLY: from various stakeholders.