Major Trends in the Development of Contemporary Chinese Art

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On the Research Status of the Storm Society

International Journal of Science Vol.2 No.12 2015 ISSN: 1813-4890 On the Research Status of the Storm Society Hao Xing School of history, Hebei University, Baoding 071002, China [email protected] Abstract The Storm Society is the first well-organized art association, which consciously absorb the western modern art achievements in Chinese modern art history. Based on the historical materials, this paper describes the basic facts of the Storm Society, and analyze the research status and weakness of this organization, and summarizes its historical and practical significance in the transformation of Chinese art from traditional form to modern form. Keywords the Storm Society, Art Magazine, research status. 1. The Basic Facts of the Storm Society The Storm Society is brewed in 1930. Its predecessor is "moss Mongolia", which is a painting group organized by Xunqin Pang, but it is soon seized. Xunqin Pang says,”I feel deeply distressed that the spirit of Chinese art and literature is decaying and corrupting, but my shallow knowledge and ability is not enough to pull the decadent a little. So I decide to gather some comrades to strive for the hope of making some contribution to the world together. This is the origin of the Storm Society.” The Storm Society is established in Nanjing in 1931, aiming at probing and developing China’s oil painting art. The main sponsors of the group are Xunqin Pang,Yide Ni , Jiyuan Wang , Zhentai Zhou , Ping Duan , Xian Zhang , Taiyang Yang , Qiuren Yang , Di Qiu , et al. The so-called "storm" means that this organization attempts to break the old barrier of traditional art, and sets off a raging tide of new art. -

(Chen Qiulin), 25F a Cheng, 94F a Xian, 276 a Zhen, 142F Abso

Index Note: “f ” with a page number indicates a figure. Anti–Spiritual Pollution Campaign, 81, 101, 102, 132, 271 Apartment (gongyu), 270 “......” (Chen Qiulin), 25f Apartment art, 7–10, 18, 269–271, 284, 305, 358 ending of, 276, 308 A Cheng, 94f internationalization of, 308 A Xian, 276 legacy of the guannian artists in, 29 A Zhen, 142f named by Gao Minglu, 7, 269–270 Absolute Principle (Shu Qun), 171, 172f, 197 in 1980s, 4–5, 271, 273 Absolution Series (Lei Hong), 349f privacy and, 7, 276, 308 Abstract art (chouxiang yishu), 10, 20–21, 81, 271, 311 space of, 305 Abstract expressionism, 22 temporary nature of, 305 “Academic Exchange Exhibition for Nationwide Young women’s art and, 24 Artists,” 145, 146f Apolitical art, 10, 66, 79–81, 90 Academicism, 78–84, 122, 202. See also New academicism Appearance of Cross Series (Ding Yi), 317f Academic realism, 54, 66–67 Apple and thinker metaphor, 175–176, 178, 180–182 Academic socialist realism, 54, 55 April Fifth Tian’anmen Demonstration (Li Xiaobin), 76f Adagio in the Opening of Second Movement, Symphony No. 5 April Photo Society, 75–76 (Wang Qiang), 108f exhibition, 74f, 75 Adam and Eve (Meng Luding), 28 Architectural models, 20 Aestheticism, 2, 6, 10–11, 37, 42, 80, 122, 200 Architectural preservation, 21 opposition to, 202, 204 Architectural sites, ritualized space in, 11–12, 14 Aesthetic principles, Chinese, 311 Art and Language group, 199 Aesthetic theory, traditional, 201–202 Art education system, 78–79, 85, 102, 105, 380n24 After Calamity (Yang Yushu), 91f Art field (yishuchang), 125 Agree -

Adults; Age Differences; *Art Education; Art Cultural Influences

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 252 457 SO 016 108 AUTHOR Hamblen, Karen A. TITLE Artistic Development as a Process of Universal-Relative Selection Possibilities. PUB DATE lot 84 NOTE 41p.; Paper presented at the National Symposium for Research in Art Education (Champaign-Urbana, IL, October 2-5, 1984). PUB TYPE Viewpoints (120) -- Information Analyses (070) Speeches /Conference Papers (150) EDRS PRICE MF01/PCO2 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Adults; Age Differences; *Art Education; Art Expression; Biological Influences; *Child Development; *Childrens Art; Cultural Context; Cultural Influences; Developmental Stages; Social Influences; *Talent Development ABSTRACT The assumptions of stage theory and major theories of child art are reviewed in order to develop an explanation of artistic expression that allows for variable andpo:nts and accounts for relationships between children's drawings and adult art. Numerous studies indicate strong similarities among children's early drawings, which suggests that primarily universal factors of influence are operative. Cross-cultural similarities and differences among adult art suggest that universal factors are still operative although relative factors predominate. A model of artistic selection possibilities is developed based on the premise that art consists of options selected from universal and relative domains, circumscribed by the imperatives of time, place, and level of skill acquisition. Similarities and differences between child and adult art as well as variable personal and cultural endpoints are accounted for when artistic development can be described as a selection process rather than a step-by-step predefined progression. (Author/KC) *********************************************************************** * Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made * * from the original document. * ***********************************************$.*********************** Universal-Relative Selection Possibilities 1 U.S. -

Performance Art

(hard cover) PERFORMANCE ART: MOTIVATIONS AND DIRECTIONS by Lee Wen Master of Arts Fine Arts 2006 LASALLE-SIA COLLEGE OF THE ARTS (blank page) PERFORMANCE ART: MOTIVATIONS AND DIRECTIONS by Lee Wen Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Degree Master of Arts (Fine Arts) LASALLE-SIA College of the Arts Faculty of Fine Arts Singapore May, 2006 ii Accepted by the Faculty of Fine Arts, LASALLE-SIA College of the Arts, In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree Master of Arts (Fine Arts). Vincent Leow Studio Supervisor Adeline Kueh Thesis Supervisor I certify that the thesis being submitted for examination is my own account of my own research, which has been conducted ethically. The data and the results presented are the genuine data and results actually obtained by me during the conduct of the research. Where I have drawn on the work, ideas and results of others this has been appropriately acknowledged in the thesis. The greater portion of the work described in the thesis has been undertaken subsequently to my registration for the degree for which I am submitting this document. Lee Wen In submitting this thesis to LASALLE-SIA College of the Arts, I understand that I am giving permission for it to be made available for use in accordance with the regulations and policies of the college. I also understand that the title and abstract will be published, and that a copy of the work may be made available and supplied to any bona fide library or research worker. This work is also subject to the college policy on intellectual property. -

Research and Education in the Contemporary Context of Art History from the Vision to the Art

3rd International Conference on Education, Management and Computing Technology (ICEMCT 2016) Research and Education in the Contemporary Context of Art History From the Vision to the Art Weikun Hao Hebei Institute of Fine Art, Shijiazhuang Hebei, 050700, China Keywords: Oil painting Techniques; Digital Image; Teaching Abstract. As is known to all, today's art education, its function has been far beyond the scope of training professional art talents. And from the perspective of the status quo of higher art education and skill training compared with history research, history research obviously in a weak position. From the Angle of art, art history is one of the important part of human art and culture, several conclusions show that for the study of art history and also learn the meaning of the obvious, such as improve the level of the fine arts disciplines, from the pure skills subject ascended to the status of the humanities; For today calls a "visual arts" or "visual culture" study, art history research is necessary; In carrying forward traditional culture today, the study of art history and learning will make human have more opportunity to participate in the fine arts with the human, and life, and emotion, contact with politics and history, for more understanding of cultural phenomenon. Introduction Plays a role in history of art history, art history research in the history of the grand is indispensable in the background, the history and culture is the concept of two inseparable. Obviously, for art history research to let a person produce both witness the massiness of history, and to experience the many things like the ramifications of fine arts. -

September/October 2016 Volume 15, Number 5 Inside

SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2016 VOLUME 15, NUMBER 5 INSI DE Chengdu Performance Art, 2012–2016 Interview with Raqs Media Collective on the 2016 Shanghai Biennale Artist Features: Cui Xiuwen, Qu Fengguo, Ying Yefu, Zhou Yilun Buried Alive: Chapter 1 US$12.00 NT$350.00 PRINTED IN TAIWAN 6 VOLUME 15, NUMBER 5, SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2016 C ONT ENT S 23 2 Editor’s Note 4 Contributors 6 Chengdu Performance Art, 2012–2016 Sophia Kidd 23 Qu Fengguo: Temporal Configurations Julie Chun 36 36 Cui Xiuwen Patricia Eichenbaum Karetzky 48 Propositioning the World: Raqs Media Collective and the Shanghai Biennale Maya Kóvskaya 59 The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly Danielle Shang 48 67 Art Labor and Ying Yefu: Between the Amateur and the Professional Jacob August Dreyer 72 Buried Alive: Chapter 1 (to be continued) Lu Huanzhi 91 Chinese Name Index 59 Cover: Zhang Yu, One Man's Walden Pond with Tire, 2014, 67 performance, one day, Lijiang. Courtesy of the artist. We thank JNBY Art Projects, Chen Ping, David Chau, Kevin Daniels, Qiqi Hong, Sabrina Xu, David Yue, Andy Sylvester, Farid Rohani, Ernest Lang, D3E Art Limited, Stephanie Holmquist, and Mark Allison for their generous contribution to the publication and distribution of Yishu. 1 Editor’s Note YISHU: Journal of Contemporary Chinese Art PRESIDENT Katy Hsiu-chih Chien LEGAL COUNSEL Infoshare Tech Law Office, Mann C. C. Liu Performance art has a strong legacy in FOUNDING EDITOR Ken Lum southwest China, particularly in the city EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Keith Wallace MANAGING EDITOR Zheng Shengtian of Chengdu. Sophia Kidd, who previously EDITORS Julie Grundvig contributed two texts on performance art in this Kate Steinmann Chunyee Li region (Yishu 44, Yishu 55), updates us on an EDITORS (CHINESE VERSION) Yu Hsiao Hwei Chen Ping art medium that has shifted emphasis over the Guo Yanlong years but continues to maintain its presence CIRCULATION MANAGER Larisa Broyde WEB SITE EDITOR Chunyee Li and has been welcomed by a new generation ADVERTISING Sen Wong of artists. -

Joan Lebold Cohen Interview Transcript

www.china1980s.org INTERVIEW TRANSCRIPT JOAN LEBOLD COHEN Interviewer: Jane DeBevoise Date:31 Oct 2009 Duration: about 2 hours Location: New York Jane DeBevoise (JD): It would be great if you could speak a little bit about how you got to China, when you got to China – with dates specific to the ‘80s, and how you saw the 80’s develop. From your perspective what were some of the key moments in terms of the arts? Joan Lebold Cohen (JC): First of all, I should say that I had been to China three times before the 1980s. I went twice in 1972, once on a delegation in May for over three weeks, which took us to Beijing, Luoyang, Xi’an, and Shanghai and we flew into Nanchang too because there were clouds over Guangzhou and the planes couldn’t fly in. This was a period when, if you wanted to have a meal and you were flying, the airplane would land so that you could go to a restaurant (Laughter). They were old, Russian airplanes, and you sat in folding chairs. The conditions were rather…primitive. But I remember going down to the Shanghai airport and having the most delicious ‘8-precious’ pudding and sweet buns – they were fantastic. I also went to China in 1978. For each trip, I had requested to meet artists and to go to exhibitions, but was denied the privilege. However, there was one time, when I went to an exhibition in May of 1972 and it was one of the only exhibitions that exhibited Cultural Revolution model paintings; it was very amusing. -

Art Market Trends Tendances Du Marché De L'art

Art market trends Tendances du marché de l'art THE WORLD LEADER IN ART MARKET INFORMATION Art market trends Tendances du marché de l'art 2005 $ 4.15 billion (€ 3.38 billion) 3.38 (€ billion 4.15 $ worldwide: auctions Art Fine at Turnover offer. on lots 320,000 of volume stable practically billion, vs. 3.6 $ billion the previous year, In despite 2005 the a turnover for record-breaking! Fine are gures Art sales fi The exceeded 4 $ well. so performed never has market art international The a million dollars, compared with compared in only 393 2004 dollars, a and million than more for hammer the under went lots 477 than less into of a rise sales 1 multiplication $ exceeding No million 19% the from translated ation on in recorded infl 2004. price This following already year, last 10.4%* of increase came on the of back a progression price incredible This Tendances du marché de l'art de marché du Tendances Art market trends trends market Art Artprice Global Index: Paris - New York - London (1994 - 2005) Base January 1994 = 100 - Quarterly data Artprice Indices are calculated with the Repeated Sales method (Econometric calculations on sales/resales of similar works) 10 000 $, 10 et 56% en deçà de 000 $.2 Ce segment est en 2005 en publiques ventes ont adjugés été moins de cette cette année, faisant suite aux d’affaires 19% mondial, de une hausse élévation déjà des A prix l’origine de de cette 10,4% incroyable progression du chiffre (3,38 d’euro) dollars de milliards milliards 4,15 : mondiales enchères Artaux Fine de ventes des Produit présentés. -

Cultural Significance and Artistic Value of Chinese Folk New Year Pictures in Traditional Festivals

2019 International Conference on Humanities, Cultures, Arts and Design (ICHCAD 2019) Cultural Significance and Artistic Value of Chinese Folk New Year Pictures in Traditional Festivals Zhiqiang Chena,*, Yongding Tanb Lingnan Normal University, Zhanjiang, 750021, China [email protected], [email protected] *Corresponding Author Keywords: New Year Pictures, Cultural Significance, Artistic Value Abstract: the History of Chinese Folk New Year Pictures Can Be Traced Back to the Han Dynasty. It Occupies an Important Position in People's Spiritual and Cultural Life and is a Valuable Cultural Heritage of the Chinese Nation. in the Long Process of Development, Chinese Traditional Folk New Year Paintings Have Formed a Unique Painting Style. Its Composition, Shape, Colour and Other Factors Have Strong Subjective Imagery, Reflecting People's Cognitive Concepts. New Year Pictures Express the Basic Spirit of Chinese Traditional Culture with the Cultural Form Closest to People and Life, Providing a Unique Spiritual Temperament for the Survival and Continuation of the Nation and Culture. It is a Popular Reading Material and Educational Reading Material for the People and Plays a Role in Popularizing Historical Knowledge and Moral Education. New Year Pictures Have Beautiful Shapes and Colours, Which Promote the Formation of People's Aesthetics, Spread Aesthetic Ideas and Form Their Own Unique Views on Shapes and Colours. 1. Introduction The Chinese culture and art have a long history, stretching from ancient times to modern times. The vast expanse of water is unbridled and brilliant, shining in the sky of world civilization. Chinese folk wood engraving New Year pictures have a long history and cover a wide range of areas in our country. -

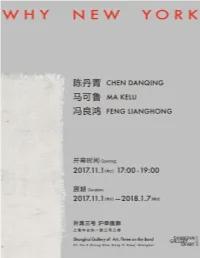

WHY-NEW-YORK-Artworks-List.Pdf

“Why New York” 是陈丹青、马可鲁、冯良鸿三人组合的第四次展览。这三位在中国当代艺术的不同阶 段各领风骚的画家在1990年代的纽约聚首,在曼哈顿和布鲁克林既丰饶又严酷的环境中白手起家,互 相温暖呵护,切磋技艺。到了新世纪,三人不约而同地回到中国,他们不忘艺术的初心,以难忘的纽约 岁月为缘由,频频举办联展。他们的组合是出于情谊,是在相互对照和印证中发现和发展各自的面目, 也是对艺术本心的坚守和砥砺。 不同于前几次带有回顾性的展览,这一次三位艺术家呈现了他们阶段性的新作。陈丹青带来了对毕加 索等西方艺术家以及中国山水及书法的研究,他呈现“画册”的绘画颇具观念性,背后有复杂的摹写、转 译、造型信息与图像意义的更替演化等话题。马可鲁的《Ada》系列在“无意识”中蕴含着规律,呈现出 书写性,在超越表面的技巧和情感因素的画面中触及“真实的自然”。冯良鸿呈现了2012年以来不同的 几种方向,在纯色色域的覆盖与黑白意境的推敲中展现视觉空间的质感。 在为展览撰写的文章中,陈丹青讲述了在归国十余年后三人作品中留有的纽约印记。这三位出生于上海 的画家此次回归家乡,又一次的聚首凝聚了岁月的光华,也映照着他们努力前行的年轻姿态。 “Why New York” marks the fourth exhibition of the artists trio, Chen Danqing, Ma Kelu and Feng Lianghong. Being the forerunners at the various stages in the progress of Chinese contemporary art, these artists first met in New York in the 1990s. In that culturally rich yet unrelenting environment of Manhattan and Brooklyn, they single-handedly launched their artistic practice, provided camaraderie to each other and exchanged ideas about art. In the new millennium, they’ve returned to China respectively. Bearing in mind their artistic ideals, their friendship and experiences of New York reunite them to hold frequent exhibitions together. With this collaboration built on friendship, they continue to discover and develop one’s own potential through the mirror of the others, as they persevere and temper in reaching their ideals in art. Unlike the previous retrospective exhibitions, the artists present their most recent works. Chen Danqing’s study on Picasso and other Western artists along with Chinese landscape painting and calligraphy is revealed in his conceptual painting “Catalogue”, a work that addresses the complex notions of drawing, translation, compositional lexicon and pictorial transformation. Ma Kelu’s “Ada” series embodies a principle of the “unconscious”, whose cursive and hyper expressive techniques adroitly integrates with the emotional elements of the painting to render “true nature”. -

Lucky Motifs in Chinese Folk Art: Interpreting Paper-Cut from Chinese Shaanxi

Asian Studies I (XVII), 2 (2013), pp. 123–141 Lucky Motifs in Chinese Folk Art: Interpreting Paper-cut from Chinese Shaanxi Xuxiao WANG Abstract Paper-cut is not simply a form of traditional Chinese folk art. Lucky motifs developed in paper-cut certainly acquired profound cultural connotations. As paper-cut is a time- honoured skill across the nation, interpreting those motifs requires cultural receptiveness and anthropological sensitivity. The author of this article analyzes examples of paper-cut from Northern Shaanxi, China, to identify the cohesive motifs and explore the auspiciousness of the specific concepts of Fu, Lu, Shou, Xi. The paper-cut of Northern Shaanxi is an ideal representative of the craft as a whole because of the relative stability of this region in history, in terms of both art and culture. Furthermore, its straightforward style provides a clear demonstration of motifs regarding folk understanding of expectations for life. Keywords: Paper-cut, Shaanxi, lucky motifs, cultural heritage Izvleček Izrezljanka iz papirja ni le ena izmed oblik tradicionalne kitajske ljudske umetnosti, saj določeni motivi sreče, ki so se razvili znotraj te umetnosti, zahtevajo poglobljeno razumevanje kulturnih konotacij. Ker je izrezljanka iz papirja častitljiva in stara veščina, ki se izdeluje po vsej državi, je za interpretacijo teh motivov potrebna kulturna receptivnost in antropološka senzitivnost. Avtorica pričujočega članka analizira primere izrezljank iz papirja iz severnega dela province Shaanxi na Kitajskem, da bi identificirala povezane motive ter raziskala dojemanje sreče in ugodnosti specifičnih konceptov, kot so Fu, Lu, Shou, Xi. Zaradi relativne stabilnosti severnega dela province Shaanxi v zgodovini, tako na področju umetnosti kot kulture, so izrezljanke iz papirja iz tega območja vzoren predstavnik rokodelstva kot celote. -

New Works by Fang Lijun Aileen June Wang

: march / april 9 March/April 2009 | Volume 8, Number 2 Inside Artist Features: Wang Guangyi, Xiao Lu, Fang Lijun, Conroy/Sanderson, Wu Gaozhong, Jin Feng Rereading the Goddess of Democracy Conversations with Zhang Peili, Jin Jiangbo US$12.00 NT$350.00 A DECLARATION OF PROTEST Late at night on February 4th, 2009, the Public Security Bureau of Chaoyang District in Beijing notified the Organizing Committee of the Twentieth Anniversary of the China/Avant- garde Exhibition that the commemorative event, which was to be held at the Beijing National Agricultural Exhibition Center on February 5th, 3 pm, must be cancelled. There was no legal basis for the provision provided. As the Head of the Preparatory Committee of the China/Avant- garde Exhibition in 1989, and the Chief Consultant and Curator of the current commemorative events, I would like to lodge a strong protest to the Public Security Bureau of Chaoyang District in Beijing. These commemorative events are legitimate cultural practices, conducted within the bounds of the Constitution of the People’s Republic of China. The Organizer and the working team have committed tremendous time, resources, and energy to launch Gao Minglu, organizer and curator of these events. Members from the art and cultural communities the events commemorating the twentieth as well as the general public are ready to participate. Without anniversary of the 1989 China/Avant-garde Exhibition, reads his protest letter in front of any prior consultation and communication, the Public Security an audience in Beijing, China on February Bureau of Chaoyang District arbitrarily issued an order to forbid 5th, 2009.