2.Jayalekshmi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Over His Long Career, the Icon of American Cinema Defined a Style of Filmmaking That Embraced the Burnished Heights of Society, Culture, and Sophistication

JAMES IVORY OVER HIS LONG CAREER, THE ICON OF AMERICAN CINEMA DEFINED A STYLE OF FILMMAKING THAT EMBRACED THE BURNISHED HEIGHTS OF SOCIETY, CULTURE, AND SOPHISTICATION. BUT JAMES IVORY AND HIS LATE PARTNER, ISMAIL MERCHANT, WERE ALSO INVETERATE OUTSIDERS WHOSE ART WAS AS POLITICALLY PROVOCATIVE AS IT WAS VISUALLY MANNERED. AT AGE 88, THE WRITER-DIRECTOR IS STILL BRINGING STORIES TO THE SCREEN THAT FEW OTHERS WOULD DARE. By CHRISTOPHER BOLLEN Photography SEBASTIAN KIM JAMES IVORY IN CLAVERACK, NY, FEBRUARY 2017. COAT: JEFFREY RUDES. SHIRT: IVORY’S OWN. On a mantle in James Ivory’s country house in but also managed to provoke, astonish, and seduce. the depths of winter. It just got to be too much, and I IVORY: I go all the time. I suppose it’s the place I love IVORY: I saw this collection of Indian miniature upstate New York sits a framed photo of actress In the case of Maurice, perhaps because the film was remember deciding to go back to New York to work most in the world. When I went to Europe for the paintings in the gallery of a dealer in San Francisco. Maggie Smith, dressed up in 1920s finery, from the so disarmingly refined and the quality of the act- on Surviving Picasso. first time, I went to Paris and then to Venice. So after I was so captivated by them. I thought, “Gosh, I’ll set of Ivory’s 1981 filmQuartet . By the fireplace in an ing and directing so strong, its central gay love story BOLLEN: The winters up here can be bleak. -

Heat and Dust

Heat and Dust Directed by James Ivory BAFTA-winning screenplay by Ruth Prawer Jhabvala, based on her Booker Prize-winning novel UK 1983, 130 mins, Cert 15 A BFI release STUNNING NEW 4K RESTORATION With Julie Christie, Shashi Kapoor, Greta Scacchi Christopher Cazenove, Madhur Jaffrey, Nickolas Grace Opening at BFI Southbank and cinemas UK-wide from 8 March 2019 20 February 2019 – Cross-cutting between the 1920s and the 1980s to tell two related stories in parallel, Merchant Ivory’s high-spirited and romantic epic of self-discovery, starring Julie Christie, Shashi Kapoor, and Greta Scacchi in her breakthrough role, is also a lush evocation of the sensuous beauty of India. Originally released in 1983, Heat and Dust returns to the big screen on 8 March 2019, beautifully restored in 4K by Cohen Media Group, New York and playing at BFI Southbank and selected cinemas UK- wide. Merchant Ivory’s Shakespeare Wallah (1965), starring Felicity Kendal and Shashi Kapoor as star-crossed lovers, will play in tandem, in an extended run at BFI Southbank from the same date, in a new restoration. In 1961, producer Ismail Merchant (1936-2005) and writer/director James Ivory (b. 1928) visited the German-born novelist Ruth Prawer Jhabvala (1927-2013), then living in Delhi, with a proposal to make a film of her novel The Householder. Jhabvala wrote the screenplay for the film herself and the legendary Merchant-Ivory-Jhabvala partnership was inaugurated, with the film released in 1963. Shakespeare Wallah, the trio’s second film together, was their first collaboration on an original project. -

Ruth Prawer Jhabvala's Adapted Screenplays

Absorbing the Worlds of Others: Ruth Prawer Jhabvala’s Adapted Screenplays By Laura Fryer Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of a PhD degree at De Montfort University, Leicester. Funded by Midlands 3 Cities and the Arts and Humanities Research Council. June 2020 i Abstract Despite being a prolific and well-decorated adapter and screenwriter, the screenplays of Ruth Prawer Jhabvala are largely overlooked in adaptation studies. This is likely, in part, because her life and career are characterised by the paradox of being an outsider on the inside: whether that be as a European writing in and about India, as a novelist in film or as a woman in industry. The aims of this thesis are threefold: to explore the reasons behind her neglect in criticism, to uncover her contributions to the film adaptations she worked on and to draw together the fields of screenwriting and adaptation studies. Surveying both existing academic studies in film history, screenwriting and adaptation in Chapter 1 -- as well as publicity materials in Chapter 2 -- reveals that screenwriting in general is on the periphery of considerations of film authorship. In Chapter 2, I employ Sandra Gilbert’s and Susan Gubar’s notions of ‘the madwoman in the attic’ and ‘the angel in the house’ to portrayals of screenwriters, arguing that Jhabvala purposely cultivates an impression of herself as the latter -- a submissive screenwriter, of no threat to patriarchal or directorial power -- to protect herself from any negative attention as the former. However, the archival materials examined in Chapter 3 which include screenplay drafts, reveal her to have made significant contributions to problem-solving, characterisation and tone. -

Ivory, James (B. 1928), and Ismail Merchant (1936-2005) by Patricia Juliana Smith

Ivory, James (b. 1928), and Ismail Merchant (1936-2005) by Patricia Juliana Smith Encyclopedia Copyright © 2015, glbtq, Inc. Entry Copyright © 2002, glbtq, Inc. Reprinted from http://www.glbtq.com Perhaps the most enduring and influential gay partnership in film history, James Ivory and Ismail Merchant are known for their visually sumptuous period pieces based on familiar literary works. So closely intertwined was this team that many assume that "Merchant Ivory" is the name of one individual. But while associated in many minds with British literary and cultural traditions, their professional and personal relationship actually brought together diverse elements of American and Indian culture. James Francis Ivory, who is the director in Merchant Ivory Productions, was born in Berkeley, California on June 7, 1928. After graduating from the University of Oregon, he received an advanced degree from the University of Southern California School of Cinema and Television in 1957. His first film was an acclaimed documentary about Venice, and his second, The Sword and the Flute, examined Indian art. In 1960, at a New York screening of this latter film, he met his future partner and collaborator. Ismail Noormohamed Abdul Rehman, later Merchant, was born December 25, 1936, in Bombay, India. He came to the United States as a student, and received an M.B.A. degree from New York University, a background that prepared him for his role as the producer and business mind of the partnership. While working for an advertising agency, he produced a film based on Indian myth, Creation of Woman (1961), which earned an Academy Award for Best Short Subject. -

Introduction – Liberal, Humanist, Modernist, Queer? Reclaiming Forster’S Legacies

Notes Introduction – Liberal, Humanist, Modernist, Queer? Reclaiming Forster’s Legacies 1. For another comprehensive monograph on different models of intertextual- ity, see Graham Allen, Intertextuality (2000). 2. See Bloom (1973). Bloom’s self-consciously idiosyncratic study has received mixed responses; its drive against formalist depersonalization has been appreciated by prominent thinkers such as Jonathan Culler, who affirms that ‘[t]urning from texts to persons, Bloom can proclaim intertextuality with a fervor less circumspect than Barthes’s, for Barthes’s tautologous naming of the intertextual as “déjà lu” [“already read”] is so anticlimactic as to preclude excited anticipations, while Bloom, who will go on to name precursors and describe the titanic struggles which take place on the battlefield of poetic tra- dition, has grounds for enthusiasm’ (1976, p. 1386; my translation). Other critics, such as Peter de Bolla, have attempted to find points of compromise between intertextuality and influence. He offers that ‘the anxiety that a poet feels in the face of his precursor poet is not something within him, it is not part of the psychic economy of a particular person, in this case a poet, rather it is the text’ (1988, p. 20). He goes on to add that ‘influence describes the relations between texts, it is an intertextual phenomenon’ (p. 28). De Bolla’s attempt at finding a crossroads between formalist intertextuality and Bloomian influence leans perhaps too strategically towards Kristeva’s more fashionable vocabulary and methodology, but it also points productively to the text as the material expression of literary influence. 3. For useful discussions and definitions of Forster’s liberal humanism, including its indebtedness to fin de siècle Cambridge, see Nicola Beauman, 1993; Peter Childs, 2007; Michael Levenson, 1991; Peter Morey, 2000; Parry, 1979; David Sidorsky, 2007. -

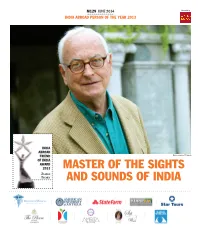

Master of the Sights and Sounds of India

M129 JUNE 2014 Presented by INDIA ABROAD PERSON OF THE YEAR 2013 INDIA ABROAD FRIEND FRANCO ORIGLIA/GETTY IMAGES OF INDIA AWARD 2013 MASTER OF THE SIGHTS JAMES IVORY AND SOUNDS OF INDIA M130 JUNE 2014 Presented by INDIA ABROAD PERSON OF THE YEAR 2013 ‘I still dream about India’ Director James Ivory , winner of the India Abroad Friend of India Award 2013 , speaks to Aseem Chhabra in his most eloquent interview yet about his elegant and memorable films set India Director James Ivory, left, and the late producer Ismail Merchant arrive at the Deauville American Film Festival in France, where Ivory was honored, in 2003. Their partnership lasted over four decades, till Merchant’s death in May 2005. James Ivory For elegantly creating a classic genre; for a repertoire of exquisitely crafted films; for taking India to the world through cinema. PHILIPPE WOJAZER/REUTERS ames Ivory’s association with India goes back nearly remember it very clearly. When we made Shakespeare Wallah it six decades when he first made two documentaries We made four feature films in a row and I think of that was much better. Plus we couldn’t see our about India. He later directed six features in India — time as a heroic period in the history of MIP ( Merchant rushes. We weren’t near any place where Jeach an iconic representation of India of that time Ivory Productions ). We had no money and it was very hard we could project rushes with sound. For period. to raise money to make the kind of films we wanted to The Householder we found a movie theater Ivory, 86, recently sat in the sprawling garden of his coun - make. -

Shashi Kapoor

NUMBER. 1 2015 SHASHI KAPOOR NATIONAL DOCUMENTATION CENTRE ON MASS COMMUNICATION NEW MEDIA WING (FORMERLY RESEARCH REFERENCE AND TRAINING DIVISION) (MINISTRY OF INFORMATION AND BROADCASTING) Room No.437-442, Phase IV, Soochana Bhavan, CGO Complex, New Delhi Compiled, Edited & Issued by National Documentation Centre on Mass Communication New Media Wing (Formerly Research, Reference & Training Division) Ministry of Information & Broadcasting Chief Editor L. R. Vishwanath Editor H. M. Sharma Assistant Editor Alka Mathur SHASHI KAPOOR Veteran actor Shashi Kapoor who is known for his considerable and versatile acting skills, a producer of off-beat films and a patron of theatre has been conferred the Dada Saheb Phakle Award for the year 2014. He is the 46th recipient of the award. He has been selected for his outstanding contribution to the growth and development of Indian cinema. He gets a Swarna Kamal, a cash prize of Rs. 10 lakh and a shawl. Shashi Kapoor was born as Balbir Raj Kapoor in Calcutta on March18, 1938 to Prithviraj Kapoor and Ramsarni Devi. He is the younger brother of Raj Kapoor and Shammi Kapoor. From the age of four, Shashi Kapoor acted in plays directed and produced by his father Prithviraj Kapoor while travelling with Prithvi Theaters. He started acting in films as a child artiste in the late 1940s appearing in commercial films including Sangram (1950) and Dana Pani (1953) under the name of Shashiraj as there was another actor by the same name who used to act in mythogical films as a child artiste. His best known performances as a child artiste were in Aag (1948) and Awaara (1951) where he played the younger version of the characters played by his brother Raj Kapoor and in Sangram (1950) where he played younger version of Ashok Kumar. -

Founders' Day Convocation (1998 Program)

Illinois Wesleyan University Digital Commons @ IWU Founders’ Day Convocations Spring 2-11-1998 Founders' Day Convocation (1998 Program) Illinois Wesleyan University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.iwu.edu/founders_day_docs Recommended Citation Illinois Wesleyan University, "Founders' Day Convocation (1998 Program)" (1998). Founders’ Day. 1. https://digitalcommons.iwu.edu/founders_day_docs/1 This Article is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Commons @ IWU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this material in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This material has been accepted for inclusion by faculty at Illinois Wesleyan University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ©Copyright is owned by the author of this document. Illinois Wesleyan University FOUNDERS’ DAY CONVOCATION Westbrook Auditorium Presser Hall February 11, 1998 11:00 A.M. PROGRAM President Minor Myers, jr., Presiding Professor Robert Mowery, Mace Bearer Organ Prelude J. Scott Ferguson, Organist Associate Professor of Music Concerto No. 1 in G major BWV592 J. S. Bach (1685-1750) *Processional Prelude Marc-Antoine Charpentier from Te Deum (circa 1645-1704) *Invocation University Chaplain Dennis E. Groh Welcome President Minor Myers, jr. Performance Ethos String Quartet String Quintet in C major Franz Peter Schuber Allegretto (1797-1828) Sharon Chung ‘00, violin Luke Herman ‘00, violin Erica Schambach ‘01, viola Karl Knapp ‘00, cello Stefan Kartman, cello Assistant Professor of Cello and Chamber Music Awarding of Honorary Degree President Minor Myers, jr. -

Octoberfest; with Cluding a Large Centerpiece Replica of In- Curtis Organ Restoration Society)

Now 31 Silent Film: “Phantom of the Op- 21 Project S.A.V.E.: Stolen Auto Veri- Garden Railway; designed by land- era”; screening of the original 1925 fication Effort; register vehicles with po- scape architect Paul Busse; large-gauge Phantom of the Opera accompanied by lice; noon-4 p.m.; Special Services De- model trains wind their way over 550 live organ music; 6 p.m.; also 8 p.m. partment, 4026 Chestnut; info: 898-4481 feet of track through intricate scale mod- University Museum; tickets available at (Special Services, Public Safety). els of historic Philadelphia buildings in- door only; info: 898-6533 (Museum; Faculty Club Octoberfest; with cluding a large centerpiece replica of In- Curtis Organ Restoration Society). beer tasting; seatings 5:30-7:30 p.m. dependence Hall. The display uses natu- International House (Reservations: 898-4618). ral materials throughout; Morris Arbore- Films, film series and events at Interna- 24 1998 Beaux Arts Ball and Din- tum. Through October 4. tional House, 3701 Chestnut St.; full de- ner—”Sites and Sounds of the Silver Shouts from the Wall: Posters and scriptions, ticket prices on-line: www. Screen: Shimmer on Sansom Street”; Photographs from the Spanish Civil libertynet.org/~ihouse or call 895-6542. War; posters, lithographs and photo- 8:30 p.m.-3 a.m.; Sansom Common, graphs brought home by American vol- 1 Fireworks (Japanese w/English 36th and Sansom; Dinner/Ball $250, call unteers. Arthur Ross Gallery. Through subtitles); 6:30 & 8:30 p.m. 569-3187; Ball Tickets ($75) 569-9700. October 4. 2 The Householder/Gbarbar (India); (Foundation for Architecture and Others). -

Merchant Ivory Interviews

Merchant-Ivory: Interviews edited by Laurence Raw (University of Mississippi Press, 2012) Perhaps the sign of a great filmmaker rests in his or her ability to foster a strong division between loyal viewers and perpetual detractors; at the very least, it would at least suggest consistency in the final product. Few contemporary filmmakers have successfully managed to cultivate a distinctive style as well as the creative team behind Merchant-Ivory Productions – so much so that James Ivory once lamented being credited with films he did not direct (and sometimes did not much care for). In his volume, Merchant-Ivory: Interviews, the latest in the Conversations with Filmmakers Series from the University of Mississippi Press, Laurence Raw ably distills this style as ‘period dramas with languid camerawork, long takes, and deep staging, long and medium shots rather than close-ups or rapid cross-cutting’ (ix). And the effect proves as intoxicating for some as it proves tiresome for others. Raw admits, ‘nothing much happens in many of their films, but we learn a lot about the characters and how they cope (or fail to cope) with cross-cultural encounters, including class-conflicts’ (xv). At a time when contemporary Hollywood cinema was growing increasingly insular and rudimentary in its narrative content, the Merchant-Ivory triumvirate – comprised of Indian producer Ismail Merchant, American director James Ivory, and their frequent collaborator, Polish-German novelist and screenwriter Ruth Prawer Jhabvala (who lived in England and India before becoming a naturalised American citizen) – produced films that maintained a strict sense of meticulous detail, literariness, and cosmopolitanism. -

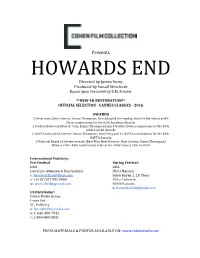

HOWARDS END Directed by James Ivory Produced by Ismail Merchant Based Upon the Novel by E.M

Presents HOWARDS END Directed by James Ivory Produced by Ismail Merchant Based upon the novel by E.M. Forster **NEW 4K RESTORATION** OFFICIAL SELECTION - CANNES CLASSICS - 2016 AWARDS 3 Oscar wins (Best Actress: Emma Thompson, Best Adapted Screenplay, Best Art Direction) and 9 Oscar nominations for the 65th Academy Awards 1 Golden Globe win (Best Actress, Emma Thompson) and 4 Golden Globe nominations for the 50th Golden Globe Awards 2 BAFTA wins (Best Actress: Emma Thompson, Best Film) and 11 BAFTA nominations for the 46th BAFTA Awards 3 National Board of Review awards (Best Film, Best Director, Best Actress: Emma Thompson) Winner of the 45th Anniversary Prize at the 1992 Cannes Film Festival International Publicity: Pre-Festival During Festival: DDA DDA Lawrence Atkinson & Paul Saunter Hotel Majestic e: [email protected] Salon Royan 1, 1st Floor t: +44 (0) 207 932 9800 10 La Croisette w: www.theddagroup.com 06400 Cannes e: [email protected] US Distributor: Cohen Media Group Laura Sok VP, Publicity e: [email protected] o: 1-646-380-7932 c: 1-860-480-4831 PRESS MATERIALS & PHOTOS AVAILABLE ON: www.cohenmedia.net NEW 4K RESTORATION AT CANNES ● 4K restoration from the original camera negative and magnetic soundtrack held at the archive of the George Eastman Museum ● Digital restoration completed by Cineric Portugal ● 5.1 audio track restoration by Audio Mechanics (Burbank) ● Color grading by Deluxe Restoration (London) under the supervision of cinematographer Tony Pierce-Roberts and director James Ivory SHORT SYNOPSIS One of Merchant Ivory’s undisputed masterpieces, this adaptation of E.M. Forster’s classic 1910 novel is a saga of class relations and changing times in Edwardian England. -

Domestic Issues in Ruth Prawer Jhabvala‟S “The Householder” a Critical Study Ruth Prawer Jhabvala

ISSN (Online) 2456 -1304 International Journal of Science, Engineering and Management (IJSEM) Vol 2, Issue 10, October 2017 Domestic issues in Ruth Prawer Jhabvala‟s “The Householder” A critical study Ruth Prawer Jhabvala CASE STUDY: failing and his career as a teacher is beset with pitfalls. At times he aspires to live like a hermit or a sanyasi under Ruth prawer jhabvala born in cologue, Germany on May the influence of a foreign hippy – like wanderer, who 7,1927. Her father, Marcus Prawer was Polish Jewish profess to be an explorer of spiritual India. In the end pre- lawyer, and her mother Eleanora had Russian discovers the true value of his young wife and attains the background. She and her elder brother Siebert Soloman status of householder in a more practical and mature way. Prawer, attended segregated Jewish schools before the It is unique, because the pervasive atmosphere is one of family moved from Nevi Germany to England as refugees humor and sympathy rather than irony, though the latter is in April 1939. After the family settled in Hendon, a not totally absent. A youth, newly married learns through suburb of London, she went to Hendon country school trial and error about privileges and pains of becoming a and then to Queen Mary college, London university, „grihastha‟. As Linda Warly mentioned: “ In Jhabvala‟s where she majored in English literature and wrote a titled novels the manner in which her characters are house – „ The story in England‟ for her M.A. degree, which she where they live, how they live and how they feel about earned in 1951.