The White Countess

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Before the Forties

Before The Forties director title genre year major cast USA Browning, Tod Freaks HORROR 1932 Wallace Ford Capra, Frank Lady for a day DRAMA 1933 May Robson, Warren William Capra, Frank Mr. Smith Goes to Washington DRAMA 1939 James Stewart Chaplin, Charlie Modern Times (the tramp) COMEDY 1936 Charlie Chaplin Chaplin, Charlie City Lights (the tramp) DRAMA 1931 Charlie Chaplin Chaplin, Charlie Gold Rush( the tramp ) COMEDY 1925 Charlie Chaplin Dwann, Alan Heidi FAMILY 1937 Shirley Temple Fleming, Victor The Wizard of Oz MUSICAL 1939 Judy Garland Fleming, Victor Gone With the Wind EPIC 1939 Clark Gable, Vivien Leigh Ford, John Stagecoach WESTERN 1939 John Wayne Griffith, D.W. Intolerance DRAMA 1916 Mae Marsh Griffith, D.W. Birth of a Nation DRAMA 1915 Lillian Gish Hathaway, Henry Peter Ibbetson DRAMA 1935 Gary Cooper Hawks, Howard Bringing Up Baby COMEDY 1938 Katharine Hepburn, Cary Grant Lloyd, Frank Mutiny on the Bounty ADVENTURE 1935 Charles Laughton, Clark Gable Lubitsch, Ernst Ninotchka COMEDY 1935 Greta Garbo, Melvin Douglas Mamoulian, Rouben Queen Christina HISTORICAL DRAMA 1933 Greta Garbo, John Gilbert McCarey, Leo Duck Soup COMEDY 1939 Marx Brothers Newmeyer, Fred Safety Last COMEDY 1923 Buster Keaton Shoedsack, Ernest The Most Dangerous Game ADVENTURE 1933 Leslie Banks, Fay Wray Shoedsack, Ernest King Kong ADVENTURE 1933 Fay Wray Stahl, John M. Imitation of Life DRAMA 1933 Claudette Colbert, Warren Williams Van Dyke, W.S. Tarzan, the Ape Man ADVENTURE 1923 Johnny Weissmuller, Maureen O'Sullivan Wood, Sam A Night at the Opera COMEDY -

The Inventory of the Joan Fontaine Collection #570

The Inventory of the Joan Fontaine Collection #570 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center TABLE OF CONTENTS Film and Video 1 Audio 3 Printed Material 5 Professional Material 10 Correspondence 13 Financial Material 50 Manuscripts 50 Photographs 51 Personal Memorabilia 65 Scrapbooks 67 Fontaine, Joan #570 Box 1 No Folder I. Film and Video. A. Video cassettes, all VHS format except where noted. In date order. 1. "No More Ladies," 1935; "Tell Me the Truth" [1 tape]. 2. "No More Ladies," 1935; "The Man Who Found Himself," 1937; "Maid's Night Out," 1938; "The Selznick Years," 1969 [1 tape]. 3. "Music for Madam," 1937; "Sky Giant," 1938; "Maid's Night Out," 1938 [1 tape]. 4. "Quality Street," 1937. 5. "A Damsel in Distress," 1937, 2 copies. 6. "The Man Who Found Himself," 1937. 7. "Maid's Night Out," 1938. 8. "The Duke ofWestpoint," 1938. 9. "Gunga Din," 1939, 2 copies. 10. "The Women," 1939, 3 copies [4 tapes; 1 version split over two tapes.] 11. "Rebecca," 1940, 3 copies. 12. "Suspicion," 1941, 4 copies. 13. "This Above All," 1942, 2 copies. 14. "The Constant Nymph," 1943. 15. "Frenchman's Creek," 1944. 16. "Jane Eyre," 1944, 3 copies. 2 Box 1 cont'd. 17. "Ivy," 1947, 2 copies. 18. "You Gotta Stay Happy," 1948. 19. "Kiss the Blood Off of My Hands," 1948. 20. "The Emperor Waltz," 1948. 21. "September Affair," 1950, 3 copies. 22. "Born to be Bad," 1950. 23. "Ivanhoe," 1952, 2 copies. 24. "The Bigamist," 1953, 2 copies. 25. "Decameron Nights," 1952, 2 copies. 26. "Casanova's Big Night," 1954, 2 copies. -

Broadway Patina Miller Leads a (Mostly) Un-Hollywood Lineup of Stellar Stage Nominees

05.23.13 • backstage.com The Tonys return to Broadway Patina Miller leads a (mostly) un-Hollywood lineup of stellar stage nominees wHo will win—and wHo sHould 0523 COV.indd 1 5/21/13 12:26 PM Be the Master Storyteller Learn to engage in the truth of a story, breathe life into characters, and create powerful moments on camera. Welcome to your craft. acting for film & television Vancouver Film School pureacting.com Vancouver Film Sch_0321_FP.indd 1 3/18/13 11:00 AM CONTENTS vol. 54, no. 21 | 05.23.13 CENTER STAGE COVER STORY Flying High 1 8 s inging, acting, dancing, and trapeze! Patina Miller secures her spot as one of Broadway’s best with her tony-nominated multi- hyphenate performance in “Pippin” FEATURES 17 2013 tony awards 22 smackdown who will—and who should— UPSTAGE take home the tony on June 9 Col a NEWS : Ni 05 take Five hair ipka what to see and where to go r in the week ahead ith DOWNSTAGE D : Ju griffith; 07 top news CASTING D Looking ahead at the 2013–14 27 new York tristate ewelry tv season Notices audition highlights heia; J 08 stage t : the Drama League opens 39 california Ng a new theater center Notices lothi in downtown Manhattan audition highlights illey;Miller: photo: Cha l ayes; C ayes; 10 screen 43 national/regional h ouise l 72 hour shootout 18 Notices gives opportunities audition highlights arah arah s to asian-americans : Chelsea CHARTS ACTOR 101 54 production stylist ; 13 Inside Job L.a.: feature films: N Dogfish accelerator upcoming co-founders James Belfer n.Y.: feature films: k salo ; lilley: Courtesy C N and Michelle soffen upcoming so N 14 the working actor 55 cast away a robi Dealing with unprofessional hey, Beantown! for roy teelu NiN co-stars D MEMBER SPOTLIGHT har C 16 secret agent Man 56 sarah Louise Lilley rit p why you could still lose your “i was once told that my roles ai k pilot job have a theme in common— : characters that are torn oftware; Dogfish: s akeup 17 tech & dIY between two choices, snapseed whether it be two worlds, two e; M N men, two cultures, or two cover photo: chad griffith personalities. -

PLAYHOUSE SQUARE January 12-17, 2016

For Immediate Release January 2016 PLAYHOUSE SQUARE January 12-17, 2016 Playhouse Square is proud to announce that the U.S. National Tour of ANNIE, now in its second smash year, will play January 12 - 17 at the Connor Palace in Cleveland. Directed by original lyricist and director Martin Charnin for the 19th time, this production of ANNIE is a brand new physical incarnation of the iconic Tony Award®-winning original. ANNIE has a book by Thomas Meehan, music by Charles Strouse and lyrics by Martin Charnin. All three authors received 1977 Tony Awards® for their work. Choreography is by Liza Gennaro, who has incorporated selections from her father Peter Gennaro’s 1977 Tony Award®-winning choreography. The celebrated design team includes scenic design by Tony Award® winner Beowulf Boritt (Act One, The Scottsboro Boys, Rock of Ages), costume design by Costume Designer’s Guild Award winner Suzy Benzinger (Blue Jasmine, Movin’ Out, Miss Saigon), lighting design by Tony Award® winner Ken Billington (Chicago, Annie, White Christmas) and sound design by Tony Award® nominee Peter Hylenski (Rocky, Bullets Over Broadway, Motown). The lovable mutt “Sandy” is once again trained by Tony Award® Honoree William Berloni (Annie, A Christmas Story, Legally Blonde). Musical supervision and additional orchestrations are by Keith Levenson (Annie, She Loves Me, Dreamgirls). Casting is by Joy Dewing CSA, Joy Dewing Casting (Soul Doctor, Wonderland). The tour is produced by TROIKA Entertainment, LLC. The production features a 25 member company: in the title role of Annie is Heidi Gray, an 11- year-old actress from the Augusta, GA area, making her tour debut. -

OFFICIAL SELECTIONS UK Films and Co-Productions at the 65Th Berlin International Film Festival

OFFICIAL SELECTIONS UK Films and Co-productions at the 65th Berlin International Film Festival UK FILM CENTRE, STAND 38, EUROPEAN FILM MARKET, MARTIN GROPIUS BAU, NIEDERKIRCHNER STR 7, 10785 BERLIN TEL: + 49 30 209159 448 Official Selections, 65th Berlin International Film Festival 2015 5 - 15 February 2015 Productions and Co-productions from the United Kingdom Competition 45 Years Andrew Haigh Cast: Charlotte Rampling, Tom Courtenay, Geraldine James, Dolly Wells, David Sibley UK Feature World Premiere Date Time Theatre 05.02.2015 21:30 CinemaxX 9 06.02.2015 15:30 CinemaxX 7 06.02.2015 15:30 CinemaxX 9 06.02.2015 22:00 Berlinale Palast 07.02.2015 10:00 Haus der Berliner Festspiele 07.02.2015 15:00 Friedrichstadt-Palast 07.02.2015 22:15 Haus der Berliner Festspiele Out of Competition Cinderella Kenneth Branagh Cast: Cate Blanchett, Lily James, Richard Madden, Stellan Skarsgard, Derek Jacobi, Helena Bonham-Carter USA/UK Feature International Premiere Date Time Theatre 13.02.2015 12:00 Berlinale Palast 13.02.2015 19:00 Berlinale Palast 14.02.2015 12:00 Friedrichstadt-Palast 15.02.2015 15:30 Berlinale Palast Mr. Holmes Bill Condon Cast: Ian McKellen, Laura Linney, Milo Parker, Hiroyuki Sanada, Hattie Morahan UK Feature World Premiere Date Time Theatre 08.02.2015 09:00 Berlinale Palast 08.02.2015 16:00 Berlinale Palast 09.02.2015 09:30 Friedrichstadt-Palast 09.02.2015 15:00 Friedrichstadt-Palast 11.02.2015 18:00 Friedrichstadt-Palast 15.02.2015 15:30 Friedrichstadt-Palast Generation/14plus Coach Ben Adler Cast: Conner Chapman, Stuart McQuarrie, -

January 2020

Abington Senior High School, Abington, PA, 19001 January 2020 Decade in Review! With the decade coming to a close a few weeks ago, the editorial staff decided that we should fl ashback to the ideas and moments that shaped the decade. As we adjust to life in the new “roaring twenties,” here is a breakdown of the most prominent events of each year from the past decade. 2010: On January 12, an earthquake registering a magnitude 7.0 on the Richter scale struck Haiti, causing about 250,000 deaths and 300,000 injuries. On March 23, the Aff ordable Care Act is signed into law by Barack Obama. Commonly referred to as “Obamacare,” it was considered one of the most extensive health care reform acts since Medicare, which was passed in 1965. On April 20, a Deepwater Horizon drilling rig exploded over the Gulf of Mexico. Killing eleven people, it is considered one of the worst oil spills in history and the largest in US waters. On July 25, Wikileaks, an organization that allows people to anonymously leak classifi ed information, released more than 90,000 documents related to the Afghanistan War. It is oft en referred to as the largest leak of classifi ed information since the Pentagon Papers during the Vietnam War. Th e New Orleans Saints won their fi rst Super Bowl since Hurricane Katrina, LeBron James made his way to Miami, Kobe Bryant won his fi nal title, and Butler went on a Cinderella run to the NCAA Championship. Th e year fi ttingly set the tone for a decade of player empowerment and underdog victories. -

Argo-Mar25-10.Pdf

ARGO by Chris Terrio Based on true events March 25, 2010 Smoke House (818) 432 0330 INT. BATHROOM STALL - DAY LUKE KNOWLES, late 20s, a slight Texan drawl. His face is bruised and his mouth is swollen. He’s cowering on the floor of the stall next to a toilet filled with vomit and shit. He speaks quietly and urgently. KNOWLES She’s looking at me, is first of all, she’s staring at me like a Chinese waiter and the dress, Shirley Temple, Good Ship Lollipop, she’s saying off, take it off her, and I hear it, school p.a., Voice of America, and it’s loud, it’s saying, This is not a clean world. This is a dirty world. So I said it, I said, ‘Here I am Lord. I got no strings to hold me down so You Show Me. You show me how to clean this dirt -- Someone -- and we can only see his back -- leans down, close to Knowles. Tries to pick him up. Knowles recoils. Then, a voice. It’s quiet, and patient, and it feels like safety. MENDEZ (O.S.) Look at me. I will help you, but you need to trust me. This is what I do. I get people out. A blank look on Knowles’s face. Unclear whether he understands this, or anything. The reverse: TONY MENDEZ, mid-40s, our hero. Fifth generation American. He’s had 19 years with the CIA and he’s the best exfiltration specialist the agency’s ever had. MENDEZ (CONT’D) Take a minute. -

Backlash Over Blair's School Revolution

Section:GDN BE PaGe:1 Edition Date:050912 Edition:01 Zone:S Sent at 11/9/2005 19:33 cYanmaGentaYellowblack Chris Patten: How the Tories lost the plot This Section Page 32 Lady Macbeth, four-letter needle- work and learning from Cate Blanchett. Judi Dench in her prime Simon Schama: G2, page 22 Amy Jenkins: America will never The me generation be the same again is now in charge G2 Page 8 G2 Page 2 £0.60 Monday 12.09.05 Published in London and Manchester guardian.co.uk Bad’day mate Aussies lose their grip Column five Backlash over The shape of things Blair’s school to come revolution Alan Rusbridger elcome to the Berliner Guardian. No, City academy plans condemned we won’t go on calling it that by ex-education secretary Morris for long, and Wyes, it’s an inel- An acceleration of plans to reform state education authorities as “commissioners egant name. education, including the speeding up of of education and champions of stan- We tried many alternatives, related the creation of the independently funded dards”, rather than direct providers. either to size or to the European origins city academy schools, will be announced The academies replace failing schools, of the format. In the end, “the Berliner” today by Tony Blair. normally on new sites, in challenging stuck. But in a short time we hope we But the increasingly controversial inner-city areas. The number of acade- can revert to being simply the Guardian. nature of the policy was highlighted when mies will rise to between 40 and 50 by Many things about today’s paper are the former education secretary Estelle next September. -

Sherlock Holmes

sunday monday tuesday wednesday thursday friday saturday KIDS MATINEE Sun 1:00! FEB 23 (7:00 & 9:00) FEB 24 & 25 (7:00 & 9:00) FEB 26 & 27 (3:00 & 7:00 & 9:15) KIDS MATINEE Sat 1:00! UP CLOUDY WITH A CHANCE OF MEATBALLS THE HURT LOCKER THE DAMNED PRECIOUS FEB 21 (3:00 & 7:00) Director: Kathryn Bigelow (USA, 2009, 131 mins; DVD, 14A) Based on the novel ‘Push’ by Sapphire FEB 22 (7:00 only) Cast: Jeremy Renner Anthony Mackie Brian Geraghty Ralph UNITED Director: Lee Daniels Fiennes Guy Pearce . (USA, 2009, 111 min; 14A) THE IMAGINARIUM OF “AN INSTANT CLASSIC!” –Wall Street Journal Director: Tom Hooper (UK, 2009, 98 min; PG) Cast: Michael Sheen, Cast: Gabourey Sidibe, Paula Patton, Mo’Nique, Mariah Timothy Spall, Colm Meaney, Jim Broadbent, Stephen Graham, Carey, Sherri Shepherd, and Lenny Kravitz “ENTERS THE PANTEHON and Peter McDonald DOCTOR PARNASSUS OF GREAT AMERICAN WAR BEST SUPPORTING ACTRESS MO’NIQUE FILMS!” –San Francisco “ONE OF THE BEST FILMS OF THE GENRE!” –Golden Globes, Screen Actors Guild Director: Terry Gilliam (UK/Canada/France, 2009, 123 min; PG) –San Francisco Chronicle Cast: Heath Ledger, Christopher Plummer, Tom Waits, Chronicle ####! The One of the most telling moments of this shockingly beautiful Lily Cole, Johnny Depp, Colin Farrell, and Jude Law Hurt Locker is about a bomb Can viewers who don’t know or care much about soccer be convinced film comes toward the end—the heroine glances at a mirror squad in present-day Iraq, to see Damned United? Those who give it a whirl will discover a and sees herself. -

Click Here to Download The

$10 OFF $10 OFF WELLNESS MEMBERSHIP MICROCHIP New Clients Only All locations Must present coupon. Offers cannot be combined. Must present coupon. Offers cannot be combined. Expires 3/31/2020 Expires 3/31/2020 Free First Office Exams FREE EXAM Extended Hours Complete Physical Exam Included New Clients Only Multiple Locations Must present coupon. Offers cannot be combined. 4 x 2” ad www.forevervets.com Expires 3/31/2020 Your Community Voice for 50 Years PONTEYour Community Voice VED for 50 YearsRA RRecorecorPONTE VEDRA dderer entertainment EEXXTRATRA! ! Featuring TV listings, streaming information, sports schedules, puzzles and more! June 25 - July 1, 2020 has a new home at INSIDE: THE LINKS! Sports listings, 1361 S. 13th Ave., Ste. 140 sports quizzes Jacksonville Beach and more Pages 18-19 Offering: · Hydrafacials · RF Microneedling · Body Contouring · B12 Complex / Lipolean Injections ‘Hamilton’ – Disney+ streams Broadway hit Get Skinny with it! “Hamilton” begins streaming Friday on Disney+. (904) 999-0977 1 x 5” ad www.SkinnyJax.com Kathleen Floryan PONTE VEDRA IS A HOT MARKET! REALTOR® Broker Associate BUYER CLOSED THIS IN 5 DAYS! 315 Park Forest Dr. Ponte Vedra, Fl 32081 Price $720,000 Beds 4/Bath 3 Built 2020 Sq Ft. 3,291 904-687-5146 [email protected] Call me to help www.kathleenfloryan.com you buy or sell. 4 x 3” ad BY GEORGE DICKIE Disney+ brings a Broadway smash to What’s Available NOW On streaming with the T American television has a proud mistreated peasant who finds her tradition of bringing award- prince, though she admitted later to winning stage productions to the nerves playing opposite decorated small screen. -

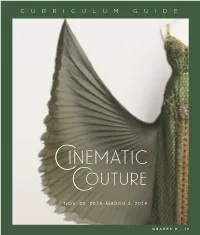

C U R R I C U L U M G U I

C U R R I C U L U M G U I D E NOV. 20, 2018–MARCH 3, 2019 GRADES 9 – 12 Inside cover: From left to right: Jenny Beavan design for Drew Barrymore in Ever After, 1998; Costume design by Jenny Beavan for Anjelica Huston in Ever After, 1998. See pages 14–15 for image credits. ABOUT THE EXHIBITION SCAD FASH Museum of Fashion + Film presents Cinematic The garments in this exhibition come from the more than Couture, an exhibition focusing on the art of costume 100,000 costumes and accessories created by the British design through the lens of movies and popular culture. costumer Cosprop. Founded in 1965 by award-winning More than 50 costumes created by the world-renowned costume designer John Bright, the company specializes London firm Cosprop deliver an intimate look at garments in costumes for film, television and theater, and employs a and millinery that set the scene, provide personality to staff of 40 experts in designing, tailoring, cutting, fitting, characters and establish authenticity in period pictures. millinery, jewelry-making and repair, dyeing and printing. Cosprop maintains an extensive library of original garments The films represented in the exhibition depict five centuries used as source material, ensuring that all productions are of history, drama, comedy and adventure through period historically accurate. costumes worn by stars such as Meryl Streep, Colin Firth, Drew Barrymore, Keira Knightley, Nicole Kidman and Kate Since 1987, when the Academy Award for Best Costume Winslet. Cinematic Couture showcases costumes from 24 Design was awarded to Bright and fellow costume designer acclaimed motion pictures, including Academy Award winners Jenny Beavan for A Room with a View, the company has and nominees Titanic, Sense and Sensibility, Out of Africa, The supplied costumes for 61 nominated films. -

January 2015

January 2015 HDNet Movies delivers the ultimate movie watching experience – uncut - uninterrupted – all in high definition. HDNet Movies showcases a diverse slate of box-office hits, iconic classics and award winners spanning the 1950s to 2000s. HDNet Movies also features kidScene, a daily and Friday Night program block dedicated to both younger movie lovers and the young at heart. For complete movie schedule information, visit www.hdnetmovies.com. Each Month HDNet Movies rolls out the red carpet and shines the spotlight on Hollywood Blockbusters, Award Winners and Memorable Movies th rd Always (Premiere) January 8 at 6:30pm The Missing (Premiere) January 3 at 8:00pm Starring Richard Dreyfuss, Holly Hunter, John Starring Tommy Lee Jones, Cate Blanchett, Evan Goodman, Audrey Hepburn. Directed by Steven Rachel Wood. Directed by Ron Howard. Spielberg. The Quick and the Dead January 3rd at 6:00pm Antwone Fisher (Premiere) January 2nd at 4:35pm Starring Sharon Stone, Gene Hackman, Russell Starring Derek Luke, Denzel Washington, Joy Bryant. Crowe, Leonardo DiCaprio. Directed by Sam Raimi. Directed by Denzel Washington. Tears of the Sun (Premiere) January 10th at th A Few Good Men January 10 at 6:30pm 9:00pm Starring Tom Cruise, Jack Nicholson, Demi Moore, Starring Bruce Willis, Monica Bellucci, Cole Hauser, Kevin Bacon. Directed by Rob Reiner. Tom Skerritt. Directed by Antoine Fuqua. Make kidScene your destination every day from 6:00am to 4:30pm. Check program schedule or www.hdnetmovies.com for all scheduled broadcasts. An American Tale January 1st at 6:00am Lego: The Adventures of Clutch Powers (Premiere) January 4th at 7:30am Featuring voices of: Christopher Plummer, Madeline Kahn, Dom DeLuise.