Biological and Cultural Diversity in the Context of Botanic Garden Conservation Strategies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

JOURNAL of the AMERICAN HORTICULTURAL SOCIETY, INC. July 1966 AMERICAN HORTICULTURAL SOCIETY

~GAZ.NE JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN HORTICULTURAL SOCIETY, INC. July 1966 AMERICAN HORTICULTURAL SOCIETY 1600 BLA DENSBURG ROA D, N O RT H EAST / W ASHIN GTON, D. c. 20002 Fo r United H orticulture *** to accum ula te, inaease, and disseminate horticultural information Editorial Committee Directors T erms Expi?'i71 g 1966 FRANCIS DE V OS, Cha irman J. H AROLD CLARKE J O H N L. CREECH Washingtoll FREDERIC P. LEE FREDERIC P. LEE Maryland CARLTON P. LEES CO~ R A D B. LI NK Massachusetts R USSELL J. S EIBERT FREnERICK C . M EYER Pennsylvan ia D ONALD WATSON WILBUR H. YOUNGMAN H awaii T erms Ex pi?'ing 1967 MRS. ROBERT L. E MERY, JR. o [ficers Louisiana A. C. HILDRETH PRESIDENT Colorado D AVID L EACH J OH N H . '''' ALKER Pennsylvania A lexand?'ia, Vi?'ginia CHARLES C . MEYER New York F IR ST VICE· PRESIDENT MRS. STANLEY ROWE Ohio F RED C. CALLE Pill e M ountain, Geo?-gia T erms Expi?-ing 1968 F RANCIS DE V OS M aryland SECON D VI CE-PRESIDENT MRS. E LSA U. K NOLL TOM D . T HROCKMORTON California Des ili/oines, I owa V ICTOR RIES Ohio S TEWART D. " ' INN ACTI NG SECRETARY·TREASURER GRACE P. 'WILSON R OBE RT WINTZ Bladensburg, Maryland Illinois The A merican Horticultural Magazine is the official publication of the American Horticultural Society and is issued four times a year during the quarters commencing with January, April, July and October. It is devoted to the dissemination of knowledge in the science and art of growing ornamental plants, fruits, vegetables, and related subjects. -

Seasonsfall 2019

SEASONSFall 2019 SEASONS FALL 2019 | A Contents SEASONS 1 A Note from the Executive Director Morris Arboretum of the 2 Ever Green Campaign Update University of Pennsylvania 4 John Shober – A Story of Giving Back Published three times a year as a benefit of membership. Inquiries concerning back issues, missing issues, or 4 Active Military Now Eligible for Free Admission subscriptions should be addressed to the editor. 5 Arboretum Welcomes New Board Members USPS: 349-830. ISSN: 0893-0546 POSTMASTER: Send form 3759 to Newsletter, 100 East Northwestern Avenue, Philadelphia, PA 19118. 5 Introducing Our Global Advisors Christine Pape, Graphic Designer/Editor 6 Climate-Resistant Trees for Our Future Public Garden Hours: 7 Women in Horticulture Mon-Fri, 10am-4pm Wed, 10am-8pm (June, July, August) 8 Stoneleigh/Morris Arboretum Volunteer Exchange A Note from the Executive Director Sat/Sun, 10am-4pm (Nov.-March) Sat/Sun, 10am-5pm (April & Oct.) 9 Arboretum Welcomes New Interns BILL CULLINA, The F. Otto Haas Executive Director Sat/Sun, 8am-5pm (May-Sept.) 10 Moonlight & Roses Information: Photo: Judy Miller (215) 247-5777 morrisarboretum.org 12 Adventures at the Arboretum upenn.edu/paflora irst, let me say hello. As you read this, I will have been the new F. Otto Haas Executive Director of the Morris Arboretum for 13 Fall Class Preview just ten short weeks, and I am truly honored and grateful for the opportunity to lead this great institution through its next Visitor Entrance: 100 East Northwestern Avenue between 13 Growing Minds chapter. The staff and community have been genuinely warm and welcoming to my family and myself, and we are all thrilled Germantown and Stenton Avenues in the Fto be here in America’s Garden Capital! Chestnut Hill section of Philadelphia 14 Arboretum Lecture Series These articles may not be reproduced in any form 14 Landscape Design Symposium without the permission of the editor. -

Utica Academy of Sci CS AR 19-20

! " ## $% & '()*+ , - . " ## !" (/ 0 / 1 )/ 2- 1 3 4 */ - 1 - 1 / 5/ - 1 / 6 1 - / - 1 1 6 / 1 ! " # $% & '( $ )* +,-.*/ , % 0,,1 *. !"#$% %$%&'() *+ $#',$' $-%."'. $-**/ 012344561475 % ! % $ #% 0*-/- *2/0,- 3- * & ' ( $ 8 34 2424 9*%.& *+ .':'," % 4 /- / 5 4 ,+ 1,*/ , !"#$% $#") & % 4*/ ,+ / *1 0*-/- ;<2413 % 4*/ + -/ ,4 +,- /-2/ , =<2413 # % *-,64 0,,1 . , -( 74,( ) ), 8 $ (# #*, "%"'('," " ! % $ !% $ " % 97 4 : 1./ -( 74,( ) ), 8 $ >') &' #:, '/'('," 9 > & ' >&' >&' ? @ @ >&' 1 $ % @ A A !% $ # ? " B !% $ ,) ! $ & !% $ !% $ " C !% $ ! !% ! $ ( D $ $ A >&' 2 + "'( ' # 6A12 !% $ A E B A "'( (D$$ & 3A& % $ - >A12 F #%& AA % !% $ "'( "'( >&' 3 : ' !% $ -

2016 ANNUAL SECURITY REPORT Jeanne Clery Disclosure of Campus Security Policy and Campus Crime Statistics Act

CAMPUS WATCH CORNELL UNIVERSITY POLICE DEPARTMENT www.cupolice.cornell.edu 2016 ANNUAL SECURITY REPORT Jeanne Clery Disclosure of Campus Security Policy and Campus Crime Statistics Act 1 Cornell is part of the county-wide emergency response system, and Cornell Police is the on-campus 911 liaison Emergency? and a primary emergency response agency. Call 9ll IMPORTANT NUMBERS What is a 911 emergency? FOR NONEMERGENCIES: It’s any situation that requires an immediate police, fire, or medical response to preserve life or property. These include: Advocacy Center (Domestic Violence ■ an assault or immediate danger of assault ■ a fight and Youth Sexual Abuse) ■ a chemical spill ■ a fire 607.277.3203 ■ someone choking ■ a serious injury or illness 607.277.5000 (24-hour hotline) ■ a crime in progress ■ a situation involving weapons ■ a drowning Cayuga Heights Police Department 607.257.1011 How can I call 911 on campus? Child Abuse and Maltreatment ■ On 253-, 254-, and 255-prefix Cornell-system phones, lift the receiver, wait for the dial tone, and press 911. There’s no need to press 9 first for an outside line. Register (New York State) 800.342.3720 ■ On Cornell Blue Light and other campus emergency phones, just lift the receiver or press the button. These phones all have a direct connection to Cornell Police Cornell Police for emergencies, assistance, or information. 607.255.1111 ■ On pay phones, lift the receiver, wait for the dial tone, and press 911. No coin is needed. Dryden Police Department ■ On other non–Cornell-system phones, lift the receiver, wait for the dial tone, 607.844.8118 and press 911. -

Get to Know Cornell

Working at Cornell Get To Know Cornell [tabs] Info Sheets Print these convenient sheets out, or pick copies up at the HR Services and Transitions Center (East Hill Office Building) About Cornell University & Ithaca This is Cornell: a brief overview of Cornell University history and structure. Places to Visit on Campus: a listing of historic locations and places of interest, as well as info about trails and tours on campus. Places to Visit in & Around Ithaca: suggestions for local arts, science, history, shopping, outdoors, events, and tours. Working at Cornell Your Rights & Responsibilities: a guide to university policies, such as the campus code of conduct, drug-free workplace, computer policies, and more. Cornell University Core Values: get to know the values that serve as a foundation for a more equitable and inclusive atmosphere at all Cornell campuses. 1 Directory - Contact Information: print out this handy list of useful contacts. CornellSpeak: some common Cornell acronyms and expressions you may encounter. Making Connections: links to news, organizations, and opportunities to connect with fellow Cornellians. Colleague Network Groups: programs for faculty and staff of traditionally underrepresented minorities and allies. Resources For Faculty: Resources for Faculty (pdf): introductory overview of benefits, governance, recognition, and resources Family Resources for Faculty (pdf): benefits and resources available to parents and those caring for dependents. Resources For Staff: Resources for Staff (pdf): introductory overview of benefits, governance, recognition, and resources. Family Resources for Staff (pdf): benefits and resources available to parents and those caring for dependents. Tours Get to know your new workplace -- virtually or in person! Ithaca Campus Tours Visit Cornell's Ithaca Campus: Sign up for a General Tour to get an introduction to Cornell's history, undergraduate colleges and schools, student life, athletics, legends and traditions. -

Public Garden

Public Garden THE JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN PUBLIC GARDENS ASSOCIATION VOLUME 34, ISSUE 1, 2019 GARDEN RELEVANCE MARKETING ALLIANCES INCLUSIVE INTERNSHIP PROGRAMS < Back to Table of Contents Public Garden is looking for your best shot! ROUGH CONSERVATORIES Send a high res, 11”X17” landscape-orientation photo for the Photosynthesis feature to [email protected]. Subject is your choice. CLEARLY SUPERIOR The Rough tradition of excellence continues at Daniel Stowe Botanical Garden. Since 1932 Rough has been building We have the experience, resources, and maintaining large, high-quality and technical expertise to solve your glazed structures, including: design needs. For more information • arboretums about Rough Brothers’ products and • botanical gardens services, call 1-800-543-7351, or visit • conservatories our website: www.roughbros.com DESIGN SERVICES 5513 Vine Street MANUFACTURING Cincinnati OH 45217 SYSTEMS INTEGRATION ph: 800 543.7351 CONSTRUCTION www.roughbros.com THE JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN PUBLIC GARDENS ASSOCIATION VOLUME 34, ISSUE 1, 2019 FOCAL POINTS 6 THE GARDEN AND THE CITY: EXPANDING RELEVANCE IN RURAL SOUTH CAROLINA This small garden is working to bring horticulture to its community as part of an effort to revitalize the city and expand people’s awareness of the garden and of horticulture. Learn how they are accomplishing this in an unique partnership. 10 ALLIANCES ENHANCE MARKETING EFFORTS Increasingly public gardens should consider alliances to strategically increase exposure, share resources, and provide greater -

Welcome Back! THURSDAY, JUNE 6 FRIDAY, JUNE 7

2019 Welcome Back! Cornell Botanic Gardens (formerly Cornell Plantations) is the arboretum, gardens and natural areas of Cornell University. At the Nevin Welcome Center and gardens on Plantations Road you can take a tour, chat with one of our wandering volunteer Garden Guides, ask a staff gardener about our plant collections and your home gardening concerns, pick up a visitor map and explore on your own, browse the exhibits and Garden Gift Shop, or just relax and enjoy the beauty and serenity of the gardens and gorges. Explore Cornell Botanic Gardens on your own using your mobile device: Take a self-guided tour of the gardens or arboretum by calling a number found on signs throughout the gardens, or use your smart phone to tour by downloading the “PocketSights” app and follow a Google- driven map that provides images and information at points of interest along the route (available from the iTunes Store or Google Play). Free parking is available at the Nevin Welcome Center, but may be limited during busy times. You can ride a Reunion shuttle to the Dairy Bar/Stocking Hall on Tower Road and walk down the footpath from there. We are also an easy to moderate walk from most points on campus. Nevin Welcome Center hours during Reunion Thursday, June 6th: 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. Friday & Saturday, June 7th-8th: 9 a.m. to 8 p.m. Sunday, June 9th: 9 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. THURSDAY, JUNE 6 Beebe Lake Natural History Walk 2:00 to 3:30 p.m., Beebe Beach Tent Did you know that Beebe Lake was originally a forested swamp, and that it is part of Cornell Botanic Gardens? Join staff botanist Robert Wesley to stroll around the lake and learn more about the history, flora, and fauna of Cornell's favorite natural area. -

Spring 2021 (PDF)

The Land Steward NEWSLETTER OF THE FINGER LAKES LAND TRUST working to protect the natural integrity of the Finger Lakes region Vol. 33, No. 2 • Spring 2021 Farmland Forever: 600 Acres Conserved in Canandaigua In 2020, the American Farmland Trust released a report analyzing the impacts of development pressure on America’s farmland. The report reveals that in New York State, 78% of farmland conversion results in low-density residential development which fragments farms piece-by- NIGEL KENT piece, and limits the long-term viability of nearby farms. protect our region’s viable Kim-Mar Farms is located just acres in 1991 and continue to purchase agricultural lands, the Land off State Route 332, north of the city neighboring parcels to grow their TO Trust works with the New of Canandaigua. In recent years, operations. Almost 500 acres of their York State Department of Agriculture and residential development pressure has property’s soils are classified as prime Markets (NYSDAM) to secure funding become intense in this area of Ontario or soils of statewide significance. They through their Farmland Protection County, given its proximity to the are committed to best management Implementation Grant program (FPIG). Rochester metropolitan area. The farm practices and work with the Ontario In partnership with NYSDAM and the is owned and operated by Kim and County Soil & Water Conservation Town of Canandaigua, the Land Trust Mark Stryker, first-generation farmers District to control erosion and recently protected 606 acres at Kim- who produce corn, wheat, soybeans, stormwater runoff. These practices are Mar Farms in the towns of Canandaigua hay, straw, and beef cattle—all of which important ecologically, as the farm and Hopewell, Ontario County, with a are sold to local markets. -

FULL PROPOSALS) 2016-2017 Strategic Tourism Implementation Funding Opportunity

APPLICATION (FULL PROPOSALS) 2016-2017 Strategic Tourism Implementation Funding Opportunity I. BASIC INFORMATION Project/Proposal Name: Tompkins Center for History and Culture Applicant Organization: The History Center in Tompkins County on behalf of the project partners Contact Person: Rod Howe Phone: 607-273-8284, ext. 222 Email: [email protected] Request: $128,000 ($28,000 in 2017 and $100,000 in 2018) Instruction: You may use up to 10 pages to answer the questions in the narrative section. II. PROPOSAL DESCRIPTION Describe your proposed project. Include a description of project deliverables and date of delivery. The Tompkins Center for History and Culture (TCHC) will bring several complementary non- profits together to become a dynamic center for Ithaca and Tompkins County. This new collaborative entity will serve as a community hub that celebrates our rich history, heritage and culture in an exciting, synergistic way. TCHC will be located on the Ithaca Commons, in the heart of Tompkins County, welcoming visitors as a gateway to the area’s many cultural destinations and serving as a gathering place for community members. The center will include staff to greet residents and visitors and to orient them to visitor services, exhibits, the library and archival resources, scheduled programs, multi- media presentations covering the history of the City and County, and a retail space. Three main goals are to 1) build community by offering opportunities to deepen connections among County residents through sharing of narratives and place based initiatives; 2) engage the public in a vibrant exploration of our unique community through history, heritage and cultural lenses; and 3) orient visitors to tourism, specifically heritage tourism, opportunities. -

1958-18--Arnoldia.Pdf

ARNOLD ARBORETUM HARVARD UNIVERSITY ARNOLDIA A continuation of the BULLETIN OF POPULAR INFORMATION VOLUME XVIII 19588 PUBLISHED BY THE ARNOLD ARBORETUM JAMAICA PLAIN, MASSACHUSETTS ARNOLDIA A continuation of the BULLETIN OF POPULAR INFORMATION of the Arnold Arboretum, Harvard University VOLUME 18s FEBRUARY 28, 1958 NUMBER I THE JUVENILE CHARACTERS OF TREES AND SHRUBS and shrubs during their life cycle pass through the stages of embry- TREESonic differentiation, juvenile development, maturity and old age. They do not produce flowers while in the juvenile stage, and even after attaining sexual maturity they may pass through a period of adolescence before settling down to reproduction. Maturity, accompamed by heavy fruitmg, usually results in the spreading posture of middle age. Trees and shrubs do, however, continue repro- duction into old age and often fruit heavily as they near the end of their life span. The juvenile stage often differs from the mature form in morphological as well as physiological characters. An outstanding example is the English Ivy, Hedera helix. The seedlings have lobed leaves on a trailing stem with aerial roots and produce no flowers, while the adult form has a more compact erect form of branch- ing, no aerial roots, entire leaves and produces flowers. Cuttings from the juvenile form produce juvemle forms while cuttings from the adult form produce compact bush-like forms. In Pecan seedlings the leaves are entire, while the adult form has compound leaves. In some varieties of ornamental apples the seedlings have tr~-lobed leaves as juveniles, but entire leaves at maturity. In some species juvenile forms may persist throughout the life of the tree. -

USA 1175-7 332 Salt Point State Park Swimming Travel Within USA 1177-81 Visas 1171-3 1009 Auburn State Recreation Traverse City 598 Volunteering 1173-4

©Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd USA ME WA New England Pacific New York, MT p184 Northwest ND New Jersey & VT Rocky Pennsylvania NH p1027 MN MA Mountains p74 OR WI MI NY ID p748 SD CT RI WY PA NJ IA Great Lakes NE MD CA p528 OH DE NV Great Plains IL UT p641 IN WV Washington, DC CO & the Capital Region KY VA California Southwest KS MO p264 p913 p816 TN NC OK The South SC AZ NM AR p344 MS AL GA Texas LA p697 Florida p464 TX FL AK Alaska p1085 Hawaii p1105 HI Trisha Ping, Isabel Albiston, Mark Baker, Amy C Balfour, Robert Balkovich, Ray Bartlett, Greg Benchwick, Andrew Bender, Alison Bing, Celeste Brash, Jade Bremner, Gregor Clark, Stephanie d’Arc Taylor, Michael Grosberg, Anthony Ham, Ashley Harrell, John Hecht, Adam Karlin, Brian Kluepfel, Ali Lemer, Vesna Maric, Virginia Maxwell, Hugh McNaughtan, MaSovaida Morgan, Becky Ohlsen, Lorna Parkes, Chris- topher Pitts, Kevin Raub, Charles Rawlings-Way, Simon Richmond, Andrea Schulte-Peevers, Regis St Louis, Ryan Ver Berkmoes, Mara Vorhees, Benedict Walker, Greg Ward, Karla Zimmerman PLAN YOUR TRIP ON THE ROAD Welcome to the USA . 6 NEW YORK, White Mountains . 250 USA Map . 8 NEW JERSEY & Hanover . 254 USA’s Top 25 . 10 PENNSYLVANIA . 74 Maine . 254 Need to Know . 22 New York City . 75 Ogunquit . 255 First Time USA . 24 New York State . 137 Portland . 255 What’s New . 26 Long Island . 137 Midcoast Maine . 259 Accommodations . 28 Hudson Valley . 143 Downeast Maine . 261 If You Like… . 30 Catskills . 146 Inland Maine . 263 Month by Month . -

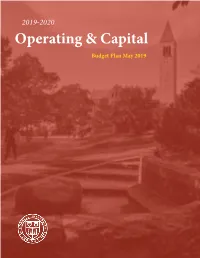

Operating & Capital

2019-2020 Operating & Capital Budget Plan May 2019 Operating and Capital Budget Plan FY2020 CONTENTS Operating Budget - Highlights Table 1: Composite Operating Budget 4 Table 2: Composite Operating Budget - by Campus 5 Operating Budget - Details Table 3: Ithaca Campus - Budget Summary 8 Table 4: Ithaca Campus - Budget Details 9 Table 5: Cornell Tech - Budget Summary 12 Table 6: Weill Cornell Medicine - Budget Summary 14 Capital Plan Table 7: Capital Activity Summary 16 Table 8: Sources & Uses of Capital Expenditures by Campus 19 Appendices A: Academic Year Tuitions 21 B: Common Student Fees 22 C: Tuition & Fees - Selected Institution Comparison 23 D: Room & Board Rates - Selected Institution Comparison 24 E: Actual & Projected Enrollments 25 F: Undergraduate Financial Aid 26 G: New York State Appropriations 27 H: Investment Assets, Returns & Payouts 28 I: Capital Activity Detail 29 J: Debt Service by Operating Unit 33 K: External Debt Financing Summary 34 L: Facilities & Administrative Costs and Employee Benefits Billing Rates 35 M: Workforce - Ithaca Campus 36 Figure 1. Fiscal Year 2020 Revenues $4.77 billion Qatar Foundation 2.0% Other Sources Sales & Services of 7.0% Tuition & Fees Enterprise 25.8% 3.7% Medical College Service Revenues Investments 30.6% 6.6% Gifts 5.4% Sponsored Programs 15.7% State & Federal Appropriations 3.2% 1 Figure 2. Fiscal Year 2020 Expenditures $4.70 billion Repairs & Debt Maintenance 1.9% Qatar 1.4% 2.7% Utilities, Rent, & Taxes 3.5% General Operations 18.0% Salaries, Wages & Capital Expenses Benefits 1.8% Financial Aid 60.1% 10.6% From the Vice President TO THE CORNELL UNIVERSITY BOARD OF TRUSTEES The Cornell University fiscal year 2020 operating and capital projects.