University Microfilms Intern Et Ionel300 N

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dynamics of Governance and Development in India a Comparative Study on Andhra Pradesh and Bihar After 1990

RUPRECHT-KARLS-UNIVERSITÄT HEIDELBERG FAKULTÄT FÜR WIRTSCHAFTS-UND SOZIALWISSENSCHAFTEN Dynamics of Governance and Development in India A Comparative Study on Andhra Pradesh and Bihar after 1990 Dissertation zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades Dr. rer. pol. an der Fakultät für Wirtschafts- und Sozialwissenschaften der Ruprecht-Karls-Universität Heidelberg Erstgutachter: Professor Subrata K. Mitra, Ph.D. (Rochester) Zweitgutachter: Professor Dr. Dietmar Rothermund vorgelegt von: Seyedhossein Zarhani Dezember 2015 Acknowledgement The completion of this thesis would not have been possible without the help of many individuals. I am grateful to all those who have provided encouragement and support during the whole doctoral process, both learning and writing. First and foremost, my deepest gratitude and appreciation goes to my supervisor, Professor Subrata K. Mitra, for his guidance and continued confidence in my work throughout my doctoral study. I could not have reached this stage without his continuous and warm-hearted support. I would especially thank Professor Mitra for his inspiring advice and detailed comments on my research. I have learned a lot from him. I am also thankful to my second supervisor Professor Ditmar Rothermund, who gave me many valuable suggestions at different stages of my research. Moreover, I would also like to thank Professor Markus Pohlmann and Professor Reimut Zohlnhöfer for serving as my examination commission members even at hardship. I also want to thank them for letting my defense be an enjoyable moment, and for their brilliant comments and suggestions. Special thanks also go to my dear friends and colleagues in the department of political science, South Asia Institute. My research has profited much from their feedback on several occasions, and I will always remember the inspiring intellectual exchange in this interdisciplinary environment. -

Reassessing Religion and Politics in the Life of Jagjivan Ram¯

religions Article Reassessing Religion and Politics in the Life of Jagjivan Ram¯ Peter Friedlander South and South East Asian Studies Program, School of Culture History and Language, College of Asia and the Pacific, Australian National University, Canberra, ACT 2600, Australia; [email protected] Received: 13 March 2020; Accepted: 23 April 2020; Published: 1 May 2020 Abstract: Jagjivan Ram (1908–1986) was, for more than four decades, the leading figure from India’s Dalit communities in the Indian National Congress party. In this paper, I argue that the relationship between religion and politics in Jagjivan Ram’s career needs to be reassessed. This is because the common perception of him as a secular politician has overlooked the role that his religious beliefs played in forming his political views. Instead, I argue that his faith in a Dalit Hindu poet-saint called Ravidas¯ was fundamental to his political career. Acknowledging the role that religion played in Jagjivan Ram’s life also allows us to situate discussions of his life in the context of contemporary debates about religion and politics. Jeffrey Haynes has suggested that these often now focus on whether religion is a cause of conflict or a path to the peaceful resolution of conflict. In this paper, I examine Jagjivan Ram’s political life and his belief in the Ravidas¯ ¯ı religious tradition. Through this, I argue that Jagjivan Ram’s career shows how political and religious beliefs led to him favoring a non-confrontational approach to conflict resolution in order to promote Dalit rights. Keywords: religion; politics; India; Congress Party; Jagjivan Ram; Ravidas;¯ Ambedkar; Dalit studies; untouchable; temple building 1. -

University Type: ALL Institution Type: University Constituted from College: ALL

Annexure-I Post-Wise Sanctioned Strength And Teaching Staff In Position State: ALL Survey Year: 2018-2019 University Type: ALL Institution Type: University Constituted From College: ALL Lecturer Name of Vice- Pro- Vice- Professor & Associate Additional Assistant Lecturer Director Principal Reader (Selection Lecturer Tutor Demonstrator Total Institution Chancellor Chancellor Equivalent Professor Professor Professor (Senior Scale) Grade) SS IP SS IP SS IP SS IP SS IP SS IP SS IP SS IP SS IP SS IP SS IP SS IP SS IP SS IP SS IP 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 ABHILASHI UNIVERSITY (Id: 1 1 14 14 5 5 14 14 102 102 5 5 141 141 U-0761) Academy of Maritime Education and 2 1 1 1 30 23 49 42 10 11 162 112 254 190 Training, Chennai (Id: U-0434) Acharya Nagarjuna 1 1 1 1 44 44 100 100 65 65 1 1 212 212 University, Guntur (Id: U-0003) Acharya NG Ranga Agricultural 15 16 41 71 79 43 352 250 487 380 University, Guntur (Id: U-0004) ADAMAS UNIVERSITY (Id: 1 1 1 1 20 18 30 14 2 2 120 128 4 4 6 6 3 3 187 177 U-0857) ADESH UNIVERSITY (Id: 1 1 7 7 51 51 30 30 20 20 14 14 101 101 17 17 49 49 7 7 36 36 333 333 U-0736) ADICHUNCHANA GIRI UNIVERSITY 1 1 1 1 5 5 21 21 25 25 11 11 46 46 1 1 111 111 (Id: U-0971) Adikavi Nannaya University, Rajahmundry, 1 1 1 1 3 3 5 5 18 18 2 2 30 30 East Godawari (Id: U-0005) AGRICULTURE UNIVERSITY, 1 1 5 3 7 6 35 7 85 55 133 72 JODHPUR (Id: U- 0703) Ahmedabad University (Id: U- 1 1 4 4 12 12 9 9 61 62 21 21 8 8 116 117 0122) AISECT UNIVERSITY (Id: 1 1 5 3 10 8 40 38 56 50 U-0850) -

India's Domestic Political Setting

Updated July 12, 2021 India’s Domestic Political Setting Overview The BJP and Congress are India’s only genuinely national India, the world’s most populous democracy, is, according parties. In previous recent national elections they together to its Constitution, a “sovereign, socialist, secular, won roughly half of all votes cast, but in 2019 the BJP democratic republic” where the bulk of executive power boosted its share to nearly 38% of the estimated 600 million rests with the prime minister and his Council of Ministers votes cast (to Congress’s 20%; turnout was a record 67%). (the Indian president is a ceremonial chief of state with The influence of regional and caste-based (and often limited executive powers). Since its 1947 independence, “family-run”) parties—although blunted by two most of India’s 14 prime ministers have come from the consecutive BJP majority victories—remains a crucial country’s Hindi-speaking northern regions, and all but 3 variable in Indian politics. Such parties now hold one-third have been upper-caste Hindus. The 543-seat Lok Sabha of all Lok Sabha seats. In 2019, more than 8,000 candidates (House of the People) is the locus of national power, with and hundreds of parties vied for parliament seats; 33 of directly elected representatives from each of the country’s those parties won at least one seat. The seven parties listed 28 states and 8 union territories. The president has the below account for 84% of Lok Sabha seats. The BJP’s power to dissolve this body. A smaller upper house of a economic reform agenda can be impeded in the Rajya maximum 250 seats, the Rajya Sabha (Council of States), Sabha, where opposition parties can align to block certain may review, but not veto, revenue legislation, and has no nonrevenue legislation (see Figure 1). -

Socio-Political Movements in North Bengal -..:: Global Group Of

Socio-Political Movements in North Bengal (A Sub-Himalayan Tract) Edited by Publish by Global Vision Publishing House Sukhbilas Barma Greater Kuch Bihar—A Utopian Movement? Sukhbilas Barma IT HAS happened every now and then—one movement followed by the other. This part of the country popularly known as North Bengal, inhabited by the major ethnic group of people, the Rajbanshis, has gone through different phases of various movements and mainly ethnic movements. One can be reminded of the Uttar Khanda movement, a movement of a section of the Rajbanshis led by Panchanan Mallik. The movement was basically on the socio-economic- political issues, the feeling of deprivation of the sons of the soil. This continued for some time; the Government paid some amount of attention to the problems of the region; people got swayed by the left ideologies, and the movement lost ground. Then came Kamtapuri movement in late 90’s, based on ethnic sentiments, which were related primarily to the feeling of subordination of the Rajbanshi language and culture. Based on the linguistic theory propounded by Dharmanarayan Barma, the leaders of Kamtapuri movement led by Atul Roy shook the socio-political environment of Dr. Sukhbilas Barma: A retired I.A.S Officer, Dr. Barma held important positions in the Government of west Bengal. 336 Socio-Political Movements in North Bengal North Bengal vigorously. The well-off sections of the Rajbanshis have lost their lands and prestige to the non- Rajbanshis hailing from East Pakistan. The poverty stricken youths have had to leave their mother land in search of livelihood. -

Strengthening of Panchayats in India: Comparing Devolution Across States

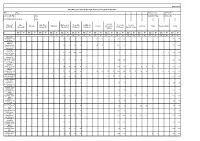

Strengthening of Panchayats in India: Comparing Devolution across States Empirical Assessment - 2012-13 April 2013 Sponsored by Ministry of Panchayati Raj Government of India The Indian Institute of Public Administration New Delhi Strengthening of Panchayats in India: Comparing Devolution across States Empirical Assessment - 2012-13 V N Alok The Indian Institute of Public Administration New Delhi Foreword It is the twentieth anniversary of the 73rd Amendment of the Constitution, whereby Panchayats were given constitu- tional status.While the mandatory provisions of the Constitution regarding elections and reservations are adhered to in all States, the devolution of powers and resources to Panchayats from the States has been highly uneven across States. To motivate States to devolve powers and responsibilities to Panchayats and put in place an accountability frame- work, the Ministry of Panchayati Raj, Government of India, ranks States and provides incentives under the Panchayat Empowerment and Accountability Scheme (PEAIS) in accordance with their performance as measured on a Devo- lution Index computed by an independent institution. The Indian Institute of Public Administration (IIPA) has been conducting the study and constructing the index while continuously refining the same for the last four years. In addition to indices on the cumulative performance of States with respect to the devolution of powers and resources to Panchayats, an index on their incremental performance,i.e. initiatives taken during the year, was introduced in the year 2010-11. Since then, States have been awarded for their recent exemplary initiatives in strengthening Panchayats. The Report on"Strengthening of Panchayats in India: Comparing Devolution across States - Empirical Assessment 2012-13" further refines the Devolution Index by adding two more pillars of performance i.e. -

Download This PDF File

The International Journal Of Humanities & Social Studies (ISSN 2321 - 9203) www.theijhss.com THE INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF HUMANITIES & SOCIAL STUDIES The Role of Babu Jagjivan Ram in the Freedom Struggle and Emancipation of Depressed Classes M. Venkatachalapathy Research Scholar, Department of History, Sri Krishnadevaraya University, Anantapur, Andhra Pradesh, India Abstract: Babu Jagjivan Ram was an eminent personality, he played vital role in freedom struggle of India and up-liftment of depressed classes economically and socially in the society. Under the leadership of Mahatma Gandhi, he worked with many people like Jawaharlal Nehru, Rajendra Prasad, and Netaji Subash Chandra Bose to get the freedom. He prisoned so many times in freedom Struggle. Since his student life, he suffered with ill-treating by the society, because he regards to backward class. So, he got realized and he started to awake the people with his ideas about the socio – economic situation of Dalits (Backward Classes) via social organizations like “Ravidas MahaSabha” and depressed classes Legue. Babu Jagajivan Ram became a crusader for social equality. Being as a nominated member of Bihar Legislative Council, he represented the oppressed classes in the council. In 1937, he founded a “ KhetiharMajdoorSabha”, which is meant for labourers and their welfare. He came out with his ideas on the current socio – economic circumstances of backward classes at “All India Depressed Classes League” in Champaran, Bihar. Therefore, Gandhi publicly said about Babu Jagjivan Ram is “Jewel” of India. So, he was such an ideal person and his life history is inspire to future of the nation. M.VENKATACHALAPATHY, Research Scholor of Sri Krishnadevaraya University, Anatapur, Andhrapradesh(India) did research on Babu Jagjivan Ram. -

Items-In-United Nations Associations (Unas) in the World

UN Secretariat Item Scan - Barcode - Record Title Page 14 Date 21/06/2006 Time 11:29:23 AM S-0990-0002-07-00001 Expanded Number S-0990-0002-07-00001 Items-in-United Nations Associations (UNAs) in the World Date Created 22/12/1973 Record Type Archival Item Container S-0990-0002: United Nations Emergency and Relief Operations Print Name of Person Submit Image Signature of Person Submit *RA/IL/SG bf .KH/ PMG/ T$/ MP cc: SG 21 October 75 X. Lehmann/sg 38O2 87S EOSG OMNIPRESS LONDON (ENGLAND) \ POPOVIC REFERENCE YOUR 317 TO HENUIG, MESSAGE PROM SECGEH ON ANNIVERSARY OF WINSCHOTElJt UK ^TOWKf WAS MAILED BY US OCTOBER 17 MSD CABLED TO DE BOER BY NETHERLANDS PERMANENT MISSION DODAY AS TELEPHONE MESSAGE FROM SECGEN NOT POSSIBLE. REGARDS, AHMED Rafeeuddin Ahmed ti at r >»"• f REFCREHCX & SEPfSMiS!? LETTS8 ' AS80CXATXOK COPIES Y0BR OFFICE PB0P8SW f © ¥IJI$0H0TE8 IfH 10^8* &fJT£H AMBASSADOR KADFE1AW UNDSETAKIMG sur THEY ®0^i APPRI OIATI sn©Hf SABLS& SECSSH es OS WITS ®&M XKSTlATS9ff GEREf&DtES LAST 88 BAY IF M01E COKVEltXEtir atrEETx ti&s TIKI at$« BEKALr« — -— S • Sit ' " 9, 20 osfc&fee* This is the text of the Secretary-General's message sent to Ms. Gerry M. de Boer on October £ waa very interested to learn of your plans to celebsrate United Nations Bay on S4 October, and the first anniversary of Winschoten ti«H. Town. I would like to congratulate the Hetlierlanfis United Nations Association and the Winschoten Committee on this imaginative programme. It is particularly rewarding and encouraging when citizens involve themselves positively ani constructively in the concerns of the United Nations. -

July 2021.Cdr

St. Norbert Campus Chronicles Vol -2, Issue 2 St. Norbert School, CBSE Affliation No: 831041, Chowhalli, T. Narasipura - 571124 July - 2021 World Day for International Justice - By Amruth world as part of an effort to recognize fact that on the same day the year 2010 decided to celebrate July the system of international criminal International Criminal Court was 17 as World Day for International justice and for the people to pay established. The International Justice. In addition, 'Social Justice in attention to serious crimes happening Criminal Court which was the Digital Economy' has been around the world. This day is also established on this day along with adopted as this year's theme to known as international criminal ratification of the Rome Statute is a celebrate the World Day for "True peace is not merely the absence justice day, which aims at the mechanism to bring to book grave International Justice. The theme of of tension but it is the presence of importance of bringing justice to crimes and ensure harsh punishment Social Justice in the Digital Justice", famous quotation by Martin people against crimes, wars and for criminals resorting to crimes at Economy also points to the large Luther King which means that genocides. The world celebrates the the international level. Apart from digital divide between haves and genuine peace requires the presence World Day for International Justice paying homage to the people and have nots. The topic is extremely of Justice, but the absence of conflict celebrating the virtues of justice organisations committed to the cause relevant for this year as with the swift and violence. -

RAJYA SABHA MONDAY, the 21ST APRIL, 2008 (The Rajya Sabha Met in the Parliament House at 11-00 A

RAJYA SABHA MONDAY, THE 21ST APRIL, 2008 (The Rajya Sabha met in the Parliament House at 11-00 a. m.) 11-00 a.m. 1. Starred Questions The following Starred Questions were orally answered:- Starred Question No. 381 regarding Cost for generation of solar energy. Starred Question No. 383 regarding Permanent benches of High Court in Orissa. Starred Question No. 386 regarding Rating of management institutions. Starred Question No. 387 regarding Declining trend of academic research. Starred Question No. 388 regarding Representation of non-teaching staff in universities. Starred Question No. 390 regarding Post-Matric scholarship for OBCs. Starred Question No. 391 regarding Committee to examine grid collapse. Answers to remaining Starred Question Nos. 382, 384, 385, 389 and 392 to 400 were laid on the Table. 2. Unstarred Questions Answers to Unstarred Question Nos. 2792 to 2946 were laid on the Table. 21ST APRIL, 2008 12-00 Noon. 3. Papers Laid on the Table Shri SushilKumar Sambhajirao Shinde (Minister of Power) laid on the Table:- I. A copy each (in English and Hindi) of the following papers under sub-section (1) of section 619A of the Companies Act, 1956:— (a) Annual Report and Accounts of the Narmada Hydroelectric Development Corporation Limited (NHDC), Bhopal, for the year 2006-2007, together with the Auditor's Report on the Accounts and the comments of the Comptroller and Auditor General of India thereon. (b) Review by Government on the working of the above Corporation. II. Statement (in English and Hindi) giving reasons for the delay in laying the papers mentioned at (1) above. -

India Freedom Fighters' Organisation

A Guide to the Microfiche Edition of Political Pamphlets from the Indian Subcontinent Part 5: Political Parties, Special Interest Groups, and Indian Internal Politics UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA A Guide to the Microfiche Edition of POLITICAL PAMPHLETS FROM THE INDIAN SUBCONTINENT PART 5: POLITICAL PARTIES, SPECIAL INTEREST GROUPS, AND INDIAN INTERNAL POLITICS Editorial Adviser Granville Austin Guide compiled by Daniel Lewis A microfiche project of UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA An Imprint of CIS 4520 East-West Highway • Bethesda, MD 20814-3389 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Indian political pamphlets [microform] microfiche Accompanied by printed guide. Includes bibliographical references. Content: pt. 1. Political Parties and Special Interest Groups—pt. 2. Indian Internal Politics—[etc.]—pt. 5. Political Parties, Special Interest Groups, and Indian Internal Politics ISBN 1-55655-829-5 (microfiche) 1. Political parties—India. I. UPA Academic Editions (Firm) JQ298.A1 I527 2000 <MicRR> 324.254—dc20 89-70560 CIP Copyright © 2000 by University Publications of America. All rights reserved. ISBN 1-55655-829-5. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ............................................................................................................................. vii Source Note ............................................................................................................................. xi Reference Bibliography Series 1. Political Parties and Special Interest Groups Organization Accession # -

Development of Regional Politics in India: a Study of Coalition of Political Partib in Uhar Pradesh

DEVELOPMENT OF REGIONAL POLITICS IN INDIA: A STUDY OF COALITION OF POLITICAL PARTIB IN UHAR PRADESH ABSTRACT THB8IS SUBMITTED FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF fioctor of ^IHloKoplip IN POLITICAL SaENCE BY TABRBZ AbAM Un<l«r tht SupMvMon of PBOP. N. SUBSAHNANYAN DEPARTMENT Of POLITICAL SCIENCE ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALI6ARH (INDIA) The thesis "Development of Regional Politics in India : A Study of Coalition of Political Parties in Uttar Pradesh" is an attempt to analyse the multifarious dimensions, actions and interactions of the politics of regionalism in India and the coalition politics in Uttar Pradesh. The study in general tries to comprehend regional awareness and consciousness in its content and form in the Indian sub-continent, with a special study of coalition politics in UP., which of late has presented a picture of chaos, conflict and crise-cross, syndrome of democracy. Regionalism is a manifestation of socio-economic and cultural forces in a large setup. It is a psychic phenomenon where a particular part faces a psyche of relative deprivation. It also involves a quest for identity projecting one's own language, religion and culture. In the economic context, it is a search for an intermediate control system between the centre and the peripheries for gains in the national arena. The study begins with the analysis of conceptual aspect of regionalism in India. It also traces its historical roots and examine the role played by Indian National Congress. The phenomenon of regionalism is a pre-independence problem which has got many manifestation after independence. It is also asserted that regionalism is a complex amalgam of geo-cultural, economic, historical and psychic factors.