Issue: the Business of Philanthropy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Givedirectly

GiveDirectly GiveDirectly provides unconditional cash transfers using cell phone technology to some of the world’s poorest people, as well as refugees, urban youth, and disaster victims. They also are currently running a historic Universal Basic Income initiative, delivering a basic income to 20,000+ people in Kenya in a 12-year study. United States (USD) Donate to GiveDirectly Please select your country & currency. Donations are tax-deductible in the country selected. Founded in Moved Delivered cash to 88% of donations sent to families 2009 US$140M 130K in poverty families Other ways to donate We recommend that gifts up to $1,000 be made online by credit card. If you are giving more than $1,000, please consider one of these alternatives. Check Bank Transfer Donor Advised Fund Cryptocurrencies Stocks or Shares Bequests Corporate Matching Program The problem: traditional methods of international giving are complex — and often inefficient Often, donors give money to a charity, which then passes along the funds to partners at the local level. This makes it difficult for donors to determine how their money will be used and whether it will reach its intended recipients. Additionally, charities often provide interventions that may not be what the recipients actually need to improve their lives. Such an approach can treat recipients as passive beneficiaries rather than knowledgeable and empowered shapers of their own lives. The solution: unconditional cash transfers Most poverty relief initiatives require complicated infrastructure, and alleviate the symptoms of poverty rather than striking at the source. By contrast, unconditional cash transfers are straightforward, providing funds to some of the poorest people in the world so that they can buy the essentials they need to set themselves up for future success. -

Non-Paywalled

Wringing the Most Good Out of a FACEBOOK FORTUNE SAN FRANCISCO itting behind a laptop affixed with a decal of a child reaching for an GIVING apple, an illustration from Shel Silverstein’s The Giving Tree, Cari Tuna quips about endowing a Tuna Room in the Bass Library at Yale Univer- sity, her alma mater. But it’s unlikely any of the fortune that she and her husband, Face- By MEGAN O’NEIL Sbook co-founder Dustin Moskovitz, command — estimated by Forbes at more than $9 billion — will ever be used to name a building. Five years after they signed the Giving Pledge, the youngest on the list of billionaires promising to donate half of their wealth, the couple is embarking on what will start at double-digit millions of dollars in giving to an eclectic range of causes, from overhauling the criminal-justice system to minimizing the potential risks from advanced artificial intelligence. To figure out where to give, they created the Open Philanthropy Project, which uses academic research, among other things, to identify high-poten- tial, overlooked funding opportunities. Ms. Tuna, a former Wall Street Journal reporter, hopes the approach will influence other wealthy donors in Silicon The youngest Valley and beyond who, like her, seek the biggest possible returns for their philanthropic dollars. Already, a co-founder of Instagram and his spouse have made a $750,000 signers of the commitment to support the project. What’s more, Ms. Tuna and those working alongside her at the Open Philanthropy Project are documenting every step online — sometimes in Giving Pledge are eyebrow-raising detail — for the world to follow along. -

Effective Altruism and Extreme Poverty

A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of Warwick Permanent WRAP URL: http://wrap.warwick.ac.uk/152659 Copyright and reuse: This thesis is made available online and is protected by original copyright. Please scroll down to view the document itself. Please refer to the repository record for this item for information to help you to cite it. Our policy information is available from the repository home page. For more information, please contact the WRAP Team at: [email protected] warwick.ac.uk/lib-publications Effective Altruism and Extreme Poverty by Fırat Akova A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Philosophy Department of Philosophy University of Warwick September 2020 Table of Contents Acknowledgments vi Declaration viii Abstract ix Introduction 1 What is effective altruism? 1 What are the premises of effective altruism? 4 The aims of this thesis and effective altruism as a field of philosophical study 11 Chapter 1 13 The Badness of Extreme Poverty and Hedonistic Utilitarianism 1.1 Introduction 13 1.2 Suffering caused by extreme poverty 15 1.3 The repugnant conclusions of hedonistic utilitarianism 17 1.3.1 Hedonistic utilitarianism can morally justify extreme poverty if it is without suffering 19 1.3.2 Hedonistic utilitarianism can morally justify the secret killing of the extremely poor 22 1.4 Agency and dignity: morally significant reasons other than suffering 29 1.5 Conclusion 35 ii Chapter 2 37 The Moral Obligation to Alleviate Extreme Poverty 2.1 Introduction -

Effective Altruism: an Elucidation and a Defence1

Effective altruism: an elucidation and a defence1 John Halstead,2 Stefan Schubert,3 Joseph Millum,4 Mark Engelbert,5 Hayden Wilkinson,6 and James Snowden7 The section on counterfactuals (the first part of section 5) has been substantially revised (14 April 2017). The advice that the Open Philanthropy Project gives to Good Ventures changed in 2016. Our paper originally set out the advice given in 2015. Abstract In this paper, we discuss Iason Gabriel’s recent piece on criticisms of effective altruism. Many of the criticisms rest on the notion that effective altruism can roughly be equated with utilitarianism applied to global poverty and health interventions which are supported by randomised control trials and disability-adjusted life year estimates. We reject this characterisation and argue that effective altruism is much broader from the point of view of ethics, cause areas, and methodology. We then enter into a detailed discussion of the specific criticisms Gabriel discusses. Our argumentation mirrors Gabriel’s, dealing with the objections that the effective altruist community neglects considerations of justice, uses a flawed methodology, and is less effective than its proponents suggest. Several of the 1 We are especially to grateful to Per-Erik Milam for his contribution to an earlier draft of this paper. For very helpful contributions and comments, we would like to thank Brian McElwee, Theron Pummer, Hauke Hillebrandt, Richard Yetter Chappell, William MacAskill, Pablo Stafforini, Owen Cotton-Barratt, Michael Page, and Nick Beckstead. We would also like to thank Rebecca Raible of GiveWell for her helpful responses to our queries, and Catherine Hollander and Holden Karnofsky of the Open Philanthropy Project for their extensive advice. -

Operational Innovations in Cash Grants to Households in Malawi

Whitepaper series - Operational Innovations in Cash Grants to Households in Malawi Program Report Date: November 2020 This whitepaper was prepared for the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) Malawi. The contents are the responsibility of GiveDirectly and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government. TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements 3 Acronyms 4 1. Executive Summary 5 2. Introduction 6 2.1. Approach: USAID - GiveDirectly Partnership 6 2.2. Introduction to GiveDirectly 8 3. Program Design 8 3.1. Operational Approach 8 3.2. Operational Innovations 11 4. Program Results 18 4.1. Use of Funds 19 4.2. Operational quality findings 21 4.3. Recipients’ Stories 22 5. Impacts of Household Grants and Recommendations for What Next 24 5.1. Gender 24 5.2. Youth Empowerment and Employment 26 5.3. Nutrition 27 5.4. Humanitarian Response 29 6. Conclusions 31 Annex 1 32 Annex 2 36 2 Acknowledgements Authors: Shaunak Ganguly, Omalha Kanjo, Mara Solomon, and Rachel Waddell at GiveDirectly This white paper was prepared for USAID/Malawi. The contents are the responsibility of GiveDirectly and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government. 3 Acronyms CDCS Country Development Cooperation Strategy GD GiveDirectly GoM Government of Malawi HEC Human Elephant Conflict IPA Innovations for Poverty Action IVR Interactive Voice Response KYC Know Your Client PIN Personal Identification Number PPE Personal Protective Equipment RCT Randomized Controlled Trial SCTP Social Cash Transfer Program UCT Unconditional Cash Transfers UNC University of North Carolina 4 1. Executive Summary As part of an ambitious, multi-country partnership and with generous support from USAID and Good Ventures, GiveDirectly (GD) successfully launched its first household grants program in Malawi in early 2019. -

Our Top Charities | Givewell

12/29/2020 Our Top Charities | GiveWell DONATE GIVING EFFECTIVELY HOW WE WORK TOP CHARITIES RESEARCH OUR MISTAKES ABOUT UPDATES HOME » TOP CHARITIES Our Top Charities Donate to high-impact, cost-effective charities—backed by evidence and analysis Updated annually — Last update: November 2020 Give Effectively Give to cost-effective, evidence-backed charities We search for charities that save or improve lives the most per dollar. These are the best we’ve found. Supported by 20,000+ hours of research annually.( 1) Donate based on evidence—not marketing Even well-meaning charities can fail to have impact. We provide evidence-backed analysis of effectiveness. Pick a charity or give to our Maximum Impact Fund We grant from our Maximum Impact Fund to the charities where we believe donations will help the most. Either way, we take zero fees. Skip to Medicine to prevent malaria Nets to prevent malaria Supplements to prevent vitamin A deficiency Cash incentives for routine childhood vaccines https://www.givewell.org/charities/top-charities 1/12 12/29/2020 Our Top Charities | GiveWell Treatments for parasitic worm infections Cash transfers for extreme poverty GiveWell’s Maximum Impact Fund CHARITY 1 OF 9 Medicine to prevent malaria Photo credit: Malaria Consortium/Sophie Garcia OVERVIEW https://www.givewell.org/charities/top-charities 2/12 12/29/2020 Our Top Charities | GiveWell Malaria kills over 400,000 people annually, mostly children under 5 in sub-Saharan Africa.( 2) Seasonal malaria chemoprevention is preventive medicine that saves children’s lives. It is given during the four months of the year when malaria infection rates are especially high. -

Effective Altruism: How Big Should the Tent Be? Amy Berg – Rhode Island College Forthcoming in Public Affairs Quarterly, 2018

Effective Altruism: How Big Should the Tent Be? Amy Berg – Rhode Island College forthcoming in Public Affairs Quarterly, 2018 The effective altruism movement (EA) is one of the most influential philosophically savvy movements to emerge in recent years. Effective Altruism has historically been dedicated to finding out what charitable giving is the most overall-effective, that is, the most effective at promoting or maximizing the impartial good. But some members of EA want the movement to be more inclusive, allowing its members to give in the way that most effectively promotes their values, even when doing so isn’t overall- effective. When we examine what it means to give according to one’s values, I argue, we will see that this is both inconsistent with what EA is like now and inconsistent with its central philosophical commitment to an objective standard that can be used to critically analyze one’s giving. While EA is not merely synonymous with act utilitarianism, it cannot be much more inclusive than it is right now. Introduction The effective altruism movement (EA) is one of the most influential philosophically savvy movements to emerge in recent years. Members of the movement, who often refer to themselves as EAs, have done a great deal to get philosophers and the general public to think about how much they can do to help others. But EA is at something of a crossroads. As it grows beyond its beginnings at Oxford and in the work of Peter Singer, its members must decide what kind of movement they want to have. -

The Institutional Critique of Effective Altruism

Forthcoming in Utilitas The Institutional Critique of Effective Altruism BRIAN BERKEY University of Pennsylvania In recent years, the effective altruism movement has generated much discussion about the ways in which we can most effectively improve the lives of the global poor, and pursue other morally important goals. One of the most common criticisms of the movement is that it has unjustifiably neglected issues related to institutional change that could address the root causes of poverty, and instead focused its attention on encouraging individuals to direct resources to organizations that directly aid people living in poverty. In this paper, I discuss and assess this “institutional critique.” I argue that if we understand the core commitments of effective altruism in a way that is suggested by much of the work of its proponents, and also independently plausible, there is no way to understand the institutional critique such that it represents a view that is both independently plausible and inconsistent with the core commitments of effective altruism. In recent years, the effective altruism movement has generated a great deal of discussion about the ways in which we (that is, at least those of us who are at least reasonably well off) can most effectively improve the lives of the global poor, and pursue other morally important goals (for example, reducing the suffering of non-human animals, or achieving criminal justice reform in the United States).1 Two of the movement’s most prominent members, Peter Singer and William MacAskill, have each produced a popular book aimed at broad audiences.2 These books, and the efforts of the movement that they represent, have in turn generated a significant amount of critical discussion. -

Rejecting Supererogationism Tarsney, Christian

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Groningen University of Groningen Rejecting Supererogationism Tarsney, Christian Published in: Pacific Philosophical Quarterly DOI: 10.1111/papq.12239 IMPORTANT NOTE: You are advised to consult the publisher's version (publisher's PDF) if you wish to cite from it. Please check the document version below. Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Publication date: 2019 Link to publication in University of Groningen/UMCG research database Citation for published version (APA): Tarsney, C. (2019). Rejecting Supererogationism. Pacific Philosophical Quarterly, 100(2), 599-623. https://doi.org/10.1111/papq.12239 Copyright Other than for strictly personal use, it is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Take-down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Downloaded from the University of Groningen/UMCG research database (Pure): http://www.rug.nl/research/portal. For technical reasons the number of authors shown on this cover page is limited to 10 maximum. Download date: 26-12-2020 REJECTING SUPEREROGATIONISM BY CHRISTIAN TARSNEY Abstract: Even if I think it very likely that some morally good act is supereroga- tory rather than obligatory, I may nonetheless be rationally required to perform that act. -

The Death of a Flamboyant Charity Wrongdoer Sends a Reminder to Regulators

November 22, 2011 The Death of a Flamboyant Charity Wrongdoer Sends a Reminder to Regulators Luc Novovitch/Reuters/Newscom William Aramony, the influential executive who built the United Way of America into a charity powerhouse but fell from grace amid fraud charges and an affair with a teenager. By Pablo Eisenberg The death this month of William Aramony, who spent six years in jail for misusing more than $1 - million in United Way of America money when he served as its chief executive, is a reminder of the time when nonprofit miscreants were larger than life, their careers marked by tremendous energy and panache compared with the current crop of unexciting executive frauds. Mr. Aramony got into nonprofit work in 1954 as an earnest and creative local United Way administrator in South Bend, Ind., where he was a much admired figure, and then moved on to executive posts in Columbia, S.C., and Miami. Flamboyant and hard-driving, he quickly established a reputation as an outstanding fund raiser and ardent spokesman for local charities. His skills did not go unnoticed at the national level. In 1970, he was appointed chief executive of the United Community Funds and Council of America, an organization he quickly renamed United Way of America. His drive, ambition, and organizational moxie enabled him to establish a strong national network of more than 2,100 independent units supporting some 47,000 charities, including the American Red Cross, Salvation Army, and a host of social-service organizations, with a total annual budget of more than $3-billion at the height of his leadership. -

Evidence-Based Development Cooperation

EVIDENCE-BASED DEVELOPMENT COOPERATION Greater Effectiveness Through Impact Evaluations POLICY PAPER Despite the unprecedented economic and technological advances of the past decades, roughly one in ten people still live in extreme poverty. This is one of the most urgent ethical problems of our time. Every year, Germany and Switzerland devote billions to development cooperation in order to create opportunities for these people. However, results from scientific research show that both countries finance extremely low-impact projects as well as highly effective ones. This paper introduces the current state of empirical research on development cooperation and recommends the following: particularly impactful projects should be promoted, and less effective projects should be ended; evaluations should be carried out more frequently as impact evaluations, and should meet academic research standards; more financial resources should be provided to achieve these goals; and Germany and Switzerland should affiliate with international research projects on impact measurement, as this would help countless people in need and simultaneously strengthen the trust of voters. January 2018 Policy paper by the Effective Altruism Foundation. Preferred citation: Vollmer, J., Pulver, T., and Zimmer, P. (2017). Evidence-based Development Cooperation: Greater effectiveness through impact evaluations. Policy paper by the Effective Altruism Foundation: 1-15. English translation: Rose Hadshar and Adrian Rorheim. For their feedback and critical input, we would like to -

990-PF Or Section 4947(A)(1) Trust Treated As Private Foundation | Do Not Enter Social Security Numbers on This Form As It May Be Made Public

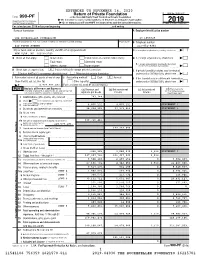

EXTENDED TO NOVEMBER 16, 2020 Return of Private Foundation OMB No. 1545-0047 Form 990-PF or Section 4947(a)(1) Trust Treated as Private Foundation | Do not enter social security numbers on this form as it may be made public. Department of the Treasury 2019 Internal Revenue Service | Go to www.irs.gov/Form990PF for instructions and the latest information. Open to Public Inspection For calendar year 2019 or tax year beginning , and ending Name of foundation A Employer identification number THE ROCKEFELLER FOUNDATION 13-1659629 Number and street (or P.O. box number if mail is not delivered to street address) Room/suite B Telephone number 420 FIFTH AVENUE 212-852-8361 City or town, state or province, country, and ZIP or foreign postal code C If exemption application is pending, check here ~ | NEW YORK, NY 10018-2702 G Check all that apply: Initial return Initial return of a former public charity D 1. Foreign organizations, check here ~~ | Final return Amended return 2. Foreign organizations meeting the 85% test, Address change Name change check here and attach computation ~~~~ | X H Check type of organization: Section 501(c)(3) exempt private foundation E If private foundation status was terminated Section 4947(a)(1) nonexempt charitable trust Other taxable private foundation under section 507(b)(1)(A), check here ~ | X I Fair market value of all assets at end of year J Accounting method: Cash Accrual F If the foundation is in a 60-month termination (from Part II, col. (c), line 16) Other (specify) under section 507(b)(1)(B), check here ~ | | $ 4,929,907,452.