Environmental Assessment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

"National List of Vascular Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands: 1996 National Summary."

Intro 1996 National List of Vascular Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands The Fish and Wildlife Service has prepared a National List of Vascular Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands: 1996 National Summary (1996 National List). The 1996 National List is a draft revision of the National List of Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands: 1988 National Summary (Reed 1988) (1988 National List). The 1996 National List is provided to encourage additional public review and comments on the draft regional wetland indicator assignments. The 1996 National List reflects a significant amount of new information that has become available since 1988 on the wetland affinity of vascular plants. This new information has resulted from the extensive use of the 1988 National List in the field by individuals involved in wetland and other resource inventories, wetland identification and delineation, and wetland research. Interim Regional Interagency Review Panel (Regional Panel) changes in indicator status as well as additions and deletions to the 1988 National List were documented in Regional supplements. The National List was originally developed as an appendix to the Classification of Wetlands and Deepwater Habitats of the United States (Cowardin et al.1979) to aid in the consistent application of this classification system for wetlands in the field.. The 1996 National List also was developed to aid in determining the presence of hydrophytic vegetation in the Clean Water Act Section 404 wetland regulatory program and in the implementation of the swampbuster provisions of the Food Security Act. While not required by law or regulation, the Fish and Wildlife Service is making the 1996 National List available for review and comment. -

The Vascular Plants of Massachusetts

The Vascular Plants of Massachusetts: The Vascular Plants of Massachusetts: A County Checklist • First Revision Melissa Dow Cullina, Bryan Connolly, Bruce Sorrie and Paul Somers Somers Bruce Sorrie and Paul Connolly, Bryan Cullina, Melissa Dow Revision • First A County Checklist Plants of Massachusetts: Vascular The A County Checklist First Revision Melissa Dow Cullina, Bryan Connolly, Bruce Sorrie and Paul Somers Massachusetts Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program The Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program (NHESP), part of the Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife, is one of the programs forming the Natural Heritage network. NHESP is responsible for the conservation and protection of hundreds of species that are not hunted, fished, trapped, or commercially harvested in the state. The Program's highest priority is protecting the 176 species of vertebrate and invertebrate animals and 259 species of native plants that are officially listed as Endangered, Threatened or of Special Concern in Massachusetts. Endangered species conservation in Massachusetts depends on you! A major source of funding for the protection of rare and endangered species comes from voluntary donations on state income tax forms. Contributions go to the Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Fund, which provides a portion of the operating budget for the Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program. NHESP protects rare species through biological inventory, -

Conference Series

Jurnal Biosains Vol. 6 No. 2 Agustus 2020 ISSN 2443-1230 (cetak) DOI: https://doi.org/10.24114/jbio.v6i2.17608 ISSN 2460-6804 (online) JBIO: JURNAL BIOSAINS (The Journal of Biosciences) http://jurnal.unimed.ac.id/2012/index.php/biosains email : [email protected] IDENTIFICATION OF MYCOHETEROTROPHIC PLANTS (Burmanniaceae, Orchidaceae, Polygalaceae, Tiuridaceae) IN NORTH SUMATRA, INDONESIA 1Dina Handayani, 1Salwa Rezeqi, 1Wina Dyah Puspita Sari, 2Yusran Efendi Ritonga, 2Hary Prakasa 1Department of Biology, FMIPA, State University of Medan, North Sumatra, Indonesia. Jl. Willem Iskandar/ Pasar V, Kenangan Baru, Medan, Sumatera Utara, Indonesia 2Biologi Pecinta Alam Sumatera Utara (BIOTA SUMUT), Gg. Obat II No.14, Sei Kera Hilir II, Kec. Medan Perjuangan, Kota Medan, Sumatera Utara 20233 Email korespondensi: [email protected] Received: Februari 2020; Revised: Juli 2020; Accepted: Agustus 2020 ABSTRACT The majority of mycoheterotrophic herbs live in shady and humid forest. Therefore, the types of mycoheterotrophic plant are very abundant in tropical areas. One of the areas in Indonesia with the tropics is North Sumatera province. Unfortunately, the information about the species of mycoheterotrophic in North Sumatra is still limited. The objective of the research was to figure out the types of mycoheterotrophic plants in North Sumatra. The study was conducted in August until October 2019 in several areas of the Natural Resources Conservation Hall (BBKSDA) of North Sumatra province, the nature Reserve and nature Park. The research sites covered Tinggi Raja Nature Reserve, Dolok Sibual-Buali Nature Reserve, Sibolangit Tourist Park and Sicike-Cike Natural Park. In conducting sampling, the method used was through exploration or cruising method. -

The Quarterly Journal of the Florida Native Plant Society

Volume 28: Number 1 > Winter/Spring 2011 PalmettoThe Quarterly Journal of the Florida Native Plant Society Protecting Endangered Plants in Panhandle Parks ● Native or Not? Carica papaya ● Water Science & Plants Protecting Endangered Plant Species Sweetwater slope: Bill and Pam Anderson To date, a total of 117 listed taxa have been recorded in 26 panhandle parks, making these parks a key resource for the protection of endangered plant species. 4 ● The Palmetto Volume 28:1 ● Winter/Spring 2011 in Panhandle State Parks by Gil Nelson and Tova Spector The Florida Panhandle is well known for its natural endowments, chief among which are its botanical and ecological diversity. Approximately 242 sensitive plant taxa occur in the 21 counties west of the Suwannee River. These include 15 taxa listed as endangered or threatened by the U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS), 212 listed as endangered or threatened by the State of Florida, 191 tracked by the Florida Natural Areas Inventory, 52 candidates for federal listing, and 7 categorized by the state as commercially exploited. Since the conservation of threatened and endangered plant species depends largely on effective management of protected populations, the occurrence of such plants on publicly or privately owned conservation lands, coupled with institutional knowledge of their location and extent is essential. District 1 of the Florida Sarracenia rosea (purple pitcherplant) at Ponce de Leon Springs State Park: Park Service manages 33 state parks encompassing approximately Tova Spector, Florida Department of Environmental Protection 53,877 acres in the 18 counties from Jefferson County and the southwestern portion of Taylor County westward. -

Alhagi Maurorum

Prepared By Jacob Higgs and Tim Higgs Class 1A EDRR- Early Detection Rapid Response Watch List Common crupina Crupina vulgaris African rue Peganum harmala Small bugloss Anchusa arvensis Mediterranean sage Salvia aethiopis Spring millet Milium vernale Syrian beancaper Zygophyllum fabago North Africa grass Ventenata dubia Plumeless thistle Carduus acanthiodes Malta thistle Centaurea melitensis Common Crupina Crupina vulgaris African rue Peganum harmala Small bugloss Anchusa arvensis Mediterranean sage Salvia aethiopis Spring millet Milium vernale Syrian beancaper Zygophyllum fabago North Africa grass Ventenata dubia Plumeless thistle Carduus acanthiodes Malta thistle Centaurea melitensis m Class 1B Early Detection Camelthorn Alhagi maurorum Garlic mustard Alliaria petiolata Purple starthistle Cantaurea calcitrapa Goatsrue Galega officinalis African mustard Brassica tournefortii Giant Reed Arundo donax Japanese Knotweed Polygonum cuspidatum Vipers bugloss Echium vulgare Elongated mustard Brassica elongate Common St. Johnswort Hypericum perforatum L. Oxeye daisy Leucanthemum vulgare Cutleaf vipergrass Scorzonera laciniata Camelthorn Alhagi maurorum Garlic mustard Alliaria petiolata Purple starthistle Cantaurea calcitrapa Goatsrue Galega officinalis African mustard Brassica tournefortii Giant Reed Arundo donax Japanese Knotweed Polygonum cuspidatum Vipers bugloss Echium vulgare Elongated mustard Brassica elongate Common St. Johnswort Hypericum perforatum L. Oxeye daisy Leucanthemum vulgare Cutleaf vipergrass Scorzonera laciniata Class 2 Control -

Minnesota and Federal Prohibited and Noxious Plants List 6-22-2011

Minnesota and Federal Prohibited and Noxious Plants List 6-22-2011 Minnesota and Federal Prohibited and Noxious Plants by Scientific Name (compiled by the Minnesota DNR’s Invasive Species Program 6-22-2011) Key: FN – Federal noxious weed (USDA–Animal Plant Health Inspection Service) SN – State noxious weed (Minnesota Department of Agriculture) RN – Restricted noxious weed (Minnesota Department of Agriculture) PI – Prohibited invasive species (Minnesota Department of Natural Resources) PS – State prohibited weed seed (Minnesota Department of Agriculture) RS – State restricted weed seed (Minnesota Department of Agriculture) (See explanations of these classifications below the lists of species) Regulatory Scientific Name Common Name Classification Aquatic Plants: Azolla pinnata R. Brown mosquito fern, water velvet FN Butomus umbellatus Linnaeus flowering rush PI Caulerpa taxifolia (Vahl) C. Agardh Mediterranean strain (killer algae) FN Crassula helmsii (Kirk) Cockayne Australian stonecrop PI Eichomia azurea (Swartz) Kunth anchored water hyacinth, rooted water FN hyacinth Hydrilla verticillata (L. f.) Royle hydrilla FN, PI Hydrocharis morsus-ranae L. European frog-bit PI Hygrophila polysperma (Roxburgh) T. Anders Indian swampweed, Miramar weed FN, PI Ipomoea aquatica Forsskal water-spinach, swamp morning-glory FN Lagarosiphon major (Ridley) Moss ex Wagner African oxygen weed FN, PI Limnophila sessiliflora (Vahl) Blume ambulia FN Lythrum salicaria L., Lythrum virgatum L., (or any purple loosestrife PI, SN variety, hybrid or cultivar thereof) Melaleuca quenquinervia (Cav.) Blake broadleaf paper bank tree FN Monochoria hastata (Linnaeus) Solms-Laubach arrowleaf false pickerelweed FN Monochoria vaginalis (Burman f.) C. Presl heart-shaped false pickerelweed FN Myriophyllum spicatum Linnaeus Eurasian water mifoil PI Najas minor All. brittle naiad PI Ottelia alismoides (L.) Pers. -

Lafayette Creek Property—Phases I and Ii Umbrella

LAFAYETTE CREEK PROPERTY—PHASES I AND II UMBRELLA REGIONAL MITIGATION PLANS FOR FLORIDA DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION PROJECTS CONCEPTUAL MITIGATION PLAN WALTON COUNTY, FLORIDA June 20, 2011 Prepared for: Mr. David Clayton Northwest Florida Water Management District 81 Water Management Drive Havana, FL 32333 Prepared by: ________________________________ ________________________________ Caitlin E. Elam Richard W. Cantrell Staff Scientist Senior Consultant 4240-034 Y100 Lafayette Creek Phases I and II Restoration Plan 062011_E.doc Lafayette Creek Property—Phases I and II Umbrella Regional Mitigation Plans for Florida Department of Transportation Projects June 20, 2011 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 PROJECT OVERVIEW AND GOALS ............................................................................. 1 2.0 LOCATION AND LANDSCAPE ...................................................................................... 2 3.0 EXISTING CONDITIONS ................................................................................................. 2 4.0 LISTED SPECIES ............................................................................................................ 13 5.0 EXOTIC SPECIES ............................................................................................................ 17 6.0 HISTORIC CONDITIONS ............................................................................................... 17 7.0 SOILS ............................................................................................................................... -

Atlas of the Flora of New England: Fabaceae

Angelo, R. and D.E. Boufford. 2013. Atlas of the flora of New England: Fabaceae. Phytoneuron 2013-2: 1–15 + map pages 1– 21. Published 9 January 2013. ISSN 2153 733X ATLAS OF THE FLORA OF NEW ENGLAND: FABACEAE RAY ANGELO1 and DAVID E. BOUFFORD2 Harvard University Herbaria 22 Divinity Avenue Cambridge, Massachusetts 02138-2020 [email protected] [email protected] ABSTRACT Dot maps are provided to depict the distribution at the county level of the taxa of Magnoliophyta: Fabaceae growing outside of cultivation in the six New England states of the northeastern United States. The maps treat 172 taxa (species, subspecies, varieties, and hybrids, but not forms) based primarily on specimens in the major herbaria of Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and Connecticut, with most data derived from the holdings of the New England Botanical Club Herbarium (NEBC). Brief synonymy (to account for names used in standard manuals and floras for the area and on herbarium specimens), habitat, chromosome information, and common names are also provided. KEY WORDS: flora, New England, atlas, distribution, Fabaceae This article is the eleventh in a series (Angelo & Boufford 1996, 1998, 2000, 2007, 2010, 2011a, 2011b, 2012a, 2012b, 2012c) that presents the distributions of the vascular flora of New England in the form of dot distribution maps at the county level (Figure 1). Seven more articles are planned. The atlas is posted on the internet at http://neatlas.org, where it will be updated as new information becomes available. This project encompasses all vascular plants (lycophytes, pteridophytes and spermatophytes) at the rank of species, subspecies, and variety growing independent of cultivation in the six New England states. -

Mimosa Diplotricha Giant Sensitive Plant

Invasive Pest Fact Sheet Asia - Pacific Forest Invasive Species Network A P F I S N Mimosa diplotricha Giant sensitive plant The Asia-Pacific Forest Invasive Species Network (APFISN) has been established as a response to the immense costs and dangers posed by invasive species to the sustainable management of forests in the Asia-Pacific region. APFISN is a cooperative alliance of the 33 member countries in the Asia-Pacific Forestry Commission (APFC) - a statutory body of the Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations (FAO). The network focuses on inter-country cooperation that helps to detect, prevent, monitor, eradicate and/or control forest invasive species in the Asia-Pacific region. Specific objectives of the network are: 1) raise awareness of invasive species throughout the Asia-Pacific region; 2) define and develop organizational structures; 3) build capacity within member countries and 4) develop and share databases and information. Distribution: South and Scientific name: Mimosa diplotricha C.Wright South-East Asia, the Pacific Synonym: Mimosa invisa Islands, northern Australia, South and Central America, the Common name: Giant sensitive plant, creeping Hawaiian Islands, parts of sensitive plant, nila grass. Africa, Nigeria and France. In India, it currently occurs Local name: Anathottawadi, padaincha (Kerala, throughout Kerala state and in India), banla saet (Cambodia), certain parts of the northeast, duri semalu (Malaysia), makahiyang lalaki especially the state of Assam. Its Flowers (Philippines), maiyaraap thao (Thailand), occurrence in other states is Cogadrogadro (Fiji). unknown and needs to be ascertained. M. diplotricha has Taxonomic position: not attained weed status in the Mimosa stem with prickles Division: Magnoliophyta Americas, Western Asia, East Class: Magnoliopsida, Order: Fabales Africa and Europe. -

Maine Coefficient of Conservatism

Coefficient of Coefficient of Scientific Name Common Name Nativity Conservatism Wetness Abies balsamea balsam fir native 3 0 Abies concolor white fir non‐native 0 Abutilon theophrasti velvetleaf non‐native 0 3 Acalypha rhomboidea common threeseed mercury native 2 3 Acer ginnala Amur maple non‐native 0 Acer negundo boxelder non‐native 0 0 Acer pensylvanicum striped maple native 5 3 Acer platanoides Norway maple non‐native 0 5 Acer pseudoplatanus sycamore maple non‐native 0 Acer rubrum red maple native 2 0 Acer saccharinum silver maple native 6 ‐3 Acer saccharum sugar maple native 5 3 Acer spicatum mountain maple native 6 3 Acer x freemanii red maple x silver maple native 2 0 Achillea millefolium common yarrow non‐native 0 3 Achillea millefolium var. borealis common yarrow non‐native 0 3 Achillea millefolium var. millefolium common yarrow non‐native 0 3 Achillea millefolium var. occidentalis common yarrow non‐native 0 3 Achillea ptarmica sneezeweed non‐native 0 3 Acinos arvensis basil thyme non‐native 0 Aconitum napellus Venus' chariot non‐native 0 Acorus americanus sweetflag native 6 ‐5 Acorus calamus calamus native 6 ‐5 Actaea pachypoda white baneberry native 7 5 Actaea racemosa black baneberry non‐native 0 Actaea rubra red baneberry native 7 3 Actinidia arguta tara vine non‐native 0 Adiantum aleuticum Aleutian maidenhair native 9 3 Adiantum pedatum northern maidenhair native 8 3 Adlumia fungosa allegheny vine native 7 Aegopodium podagraria bishop's goutweed non‐native 0 0 Coefficient of Coefficient of Scientific Name Common Name Nativity -

Eastern North American Plants in Cultivation

Eastern North American Plants in Cultivation Many indigenous North American plants are in cultivation, but many equally worthy ones are seldom grown. It often ap- pears that familiar native plants are taken for granted, while more exotic ones - those with the glamor of coming from some- where else - are more commonly cultivated. Perhaps this is what happens everywhere, but perhaps this attitude is a hand- me-down from the time when immigrants to the New World brought with them plants that tied them to the Old. At any rate, in the eastern United States some of the most commonly culti- vated plants are exotic species such as Forsythia species and hy- brids, various species of Ligustrum, Syringa vulgaris, Ilex cre- nata, Magnolia X soulangiana, Malus species and hybrids, Acer platanoides, Asiatic rhododendrons (both evergreen and decidu- ous) and their hybrids, Berberis thunbergii, Abelia X grandi- flora, Vinca minor, and Pachysandra procumbens, to mention only a few examples. This is not to imply, however, that there are few indigenous plants that have "made the grade," horticulturally speaking, for there are many obvious successes. Some plants, such as Cornus florida, have been adopted immediately and widely, but others, such as Phlox stolonifera ’Blue Ridge’ have had to re- ceive an award in Europe before drawing the attention they de- serve here, much as American singers used to have to acquire a foreign reputation before being accepted as worthwhile artists. Examples among the widely grown eastern American trees are Tsuga canadensis; Thuja occidentalis; Pinus strobus (and other species); Quercus rubra, Q. palustris, and Q. -

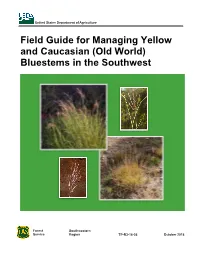

Field Guide for Managing Yellow and Caucasian (Old World) Bluestems in the Southwest

USDA United States Department of Agriculture - Field Guide for Managing Yellow and Caucasian (Old World) Bluestems in the Southwest Forest Southwestern Service Region TP-R3-16-36 October 2018 Cover Photos Top left — Yellow bluestem; courtesy photo by Max Licher, SEINet Top right — Yellow bluestem panicle; courtesy photo by Billy Warrick; Soil, Crop and More Information Lower left — Caucasian bluestem panicle; courtesy photo by Max Licher, SEINet Lower right — Caucasian bluestem; courtesy photo by Max Licher, SEINet Authors Karen R. Hickman — Professor, Oklahoma State University, Stillwater OK Keith Harmoney — Range Scientist, KSU Ag Research Center, Hays KS Allen White — Region 3 Pesticides/Invasive Species Coord., Forest Service, Albuquerque NM Citation: USDA Forest Service. 2018. Field Guide for Managing Yellow and Caucasian (Old World) Bluestems in the Southwest. Southwestern Region TP-R3-16-36, Albuquerque, NM. In accordance with Federal civil rights law and U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) civil rights regulations and policies, the USDA, its Agencies, offices, and employees, and institutions participating in or administering USDA programs are prohibited from discriminating based on race, color, national origin, religion, sex, gender identity (including gender expression), sexual orientation, disability, age, marital status, family/parental status, income derived from a public assistance program, political beliefs, or reprisal or retaliation for prior civil rights activity, in any program or activity conducted or funded by USDA (not all bases apply to all programs). Remedies and complaint filing deadlines vary by program or incident. Persons with disabilities who require alternative means of communication for program information (e.g., Braille, large print, audiotape, American Sign Language, etc.) should contact the responsible Agency or USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TTY) or contact USDA through the Federal Relay Service at (800) 877-8339.