Journal of Northwest Anthropology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Squamish Community: Our People and Places Teacher’S Package

North Vancouver MUSEUM & ARCHIVES SCHOOL PROGRAMS 2018/19 Squamish Community: Our People and Places Teacher’s Package Grade 3 - 5 [SQUAMISH COMMUNITY: OUR PEOPLE AND PLACES KIT] Introduction SQUAMISH COMMUNITY: OUR PEOPLE AND PLACES KIT features 12 archival photographs selected from the Skwxwú7mesh Úxwumixw: The Squamish Community: Our People and Places exhibit presented at the North Vancouver Museum & Archives in 2010. This exhibit was a collaborative project undertaken by the North Vancouver Museum & Archives and the Squamish Nation. These archival images were selected by the Squamish Elders and Language Authority to represent local landscapes, the community and the individual people within the Squamish Nation. The Squamish Elders and Language Authority also contributed to the exhibit labels which are included on the reverse of each picture. This Kit has been designed to complement BC’s Social Studies curriculum for grades 3 - 5, giving students the opportunity to explore themes related to First Nations cultures in the past and cultural First Nations activities today. Included within this Kit is a detailed teacher’s package that provides instructors with lesson plan activities that guide students in the analysis of archival photographs. The recommended activities encourage skills such as critical thinking and cooperative learning. Altogether, the lesson plan activities are estimated to take 1 hour and 45 minutes and can easily be stretched across several instructional days. Through photo analysis worksheets and activities, students will be introduced to the Squamish Nation and historical photographs. Teachers are encouraged to read through the program and adapt it to meet the learning abilities and individual needs of their students. -

Office of the Reservation Attorney Director Takes Oath Of

SXwlemiUU NationO NewsL U SSQUOLLQQUOLO LNovember 2019 LummiL Communications - 2665 Kwina Road - Bellingham, WashingtonL 98226 UULummiO IndianLQ BusinessUU Newly Lummi Indian Business OCouncil Seat Vacancy Elected Council Members 2019 For Immediate Release and relationship building November 20, 2019 across Indian Country and United States. We want to On November 18, 2019 thank Councilman Julius for the Lummi Indian Business everything he has done for Council (LIBC) gave a sum- our people. Thank you for mary of the report to the Gen- your leadership, thank you eral Council, which clearly for always answering the call, showed that there were no thank you for carrying on the findings in response to theteachings of your elders and anonymous allegations. The ancestors to appreciate and - official report cleared all par fight for life, culture and our ties identified. homeland. Also, thank you to On November 18, 2019, the Julius and Lane families Councilman Julius submit- for allowing Jay the time to ted his resignation letter to serve the Lummi Nation. the Lummi Indian Business Council due to the duress he In accordance with Arti- and his family experienced cle V, Section 1 and Article IV, as a result of the anonymous Section 2 of the Constitution accusations. and Bylaws of the Lummi Tribe, the LIBC will appoint On November 19, 2019 a qualified tribal member Photo credit Lummi Communications the LIBC accepted the letter to fill the remaining term of Photo taken at Swearing In of Council Members November 5, 2019 of resignation from Council- Position D (on reservation) man Julius. at the next regular or special Chairman - Lawrence Solomon Councilman Julius served LIBC meeting. -

Society for Historical Archaeology

Historical Archaeology Volume 46, Number 42 2012 Journal of The Society for Historical Archaeology J. W. JOSEPH, Editor New South Associates, Inc. 6150 East Ponce de Leon Avenue Stone Mountain, Georgia 30083 InN assocASSOCIATIONIatIon wWITHIth aRudreyEBECCA h ornALLENIng,, JcAMIEhrIs BMRANDONatthews, ,C MHRISargaret MATTHEWS Purser, , andPAUL g MraceULLINS ZIes, DIngELLA, a ssocSCOTTIate-I RETONedItors, B; RENT WEISMAN, GRACE ZEISING, rASSOCIATEIchard V eEItDITORS, reVIews; CHARLES edItor ;E MWENary, RBEVIEWSeth reed EDITOR, co;- eMdARYItor BETH REED, CO-EDITOR Published by THE SOCIETY FOR HISTORICAL ARCHAEOLOGY Front Matter - 46(2) for print.indd i 9/7/12 9:28 AM HISTORICAL ARCHAEOLOGY IS INDEXED IN THE FOLLOWING PUBLICATIONS: ABSTRACTS OF ANTHROPOLOGY; AMERICA: HISTORY AND LIFE; ANTHROPOLOGICAL LITERATURE; ART AND ARCHAEOLOGY TECHNICAL ABSTRACTS; ARTS AND HUMANITIES INDEX; BRITISH ARCHAEOLOGICAL ABSTRACTS; CURRENT CONTENTS/ ARTS AND HUMANITIES; HISTORICAL ABSTRACTS; HUMANITIES INDEX; AND INTERNATIONAL BIBLIOGRAPHY OF THE SOCIAL SCIENCES. Copyediting by Richard G. Schaefer Composition by OneTouchPoint/Ginny’s Printing Austin, Texas ©2012 by The Society for Historical Archaeology Printed in the United States of America ISSN 0440-9213 The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences–Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984. Contents Volume 46, No. 4, 2012 MEMORIAL RODERICK SPRAGUE 1933–2012 1 ARTICLES “Their Houses are Ancient and Ordinary”: Archaeology and Connecticut’s Eighteenth-Century Domestic Architecture ROSS K. HARPER 8 Evaluating Spanish Colonial Alternative Economies in the Archaeological Record AMANDA D. ROBERTS THOMPSON 48 Pueblo Potsherds to Silver Spoons: A Case Study in Historical Archaeology from New Mexico MELISSA PAYNE 70 Hard Labor and Hostile Encounters: What Human Remains Reveal about Institutional Violence and Chinese Immigrants Living in Carlin, Nevada (1885–1923) RYAN P. -

Traditional and Naturally Significant Places Process Primer for the Oglala Sioux Tribe

St. Cloud State University theRepository at St. Cloud State Culminating Projects in Cultural Resource Management Department of Anthropology 12-2019 Traditional and Naturally Significant Places Process Primer for the Oglala Sioux Tribe Michael Catches Enemy Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.stcloudstate.edu/crm_etds Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Catches Enemy, Michael, "Traditional and Naturally Significant Places Process Primer for the Oglala Sioux Tribe" (2019). Culminating Projects in Cultural Resource Management. 32. https://repository.stcloudstate.edu/crm_etds/32 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Anthropology at theRepository at St. Cloud State. It has been accepted for inclusion in Culminating Projects in Cultural Resource Management by an authorized administrator of theRepository at St. Cloud State. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Traditional and Naturally Significant Places Process Primer for the Oglala Sioux Tribe by Michael Bryan Catches Enemy, Sr. A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of St. Cloud State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science in Cultural Resource Management Archaeology December, 2019 Starred Paper Committee: Mark Muñiz Darlene St. Clair Kelly Branam 2 Abstract The Oglala Sioux Tribe, through its various tribal programs like the Historic Preservation Office & the Cultural Affairs Advisory Council (2009-2013), decided to initiate the development of a process primer for the future creation of a more holistic and culturally-relevant identification process for Lakólyakel na ečhá waŋkátuya yawá owáŋka “traditional and naturally significant places” (TNSP’s) to protect and preserve these places within the realm of cultural resource management. -

Dr. Brett R. Lenz

COLONIZER GEOARCHAEOLOGY OF THE PACIFIC NORTHWEST REGION A Dissertation DR. BRETT R. LENZ COLONIZER GEOARCHAEOLOGY OF THE PACIFIC NORTHWEST REGION, NORTH AMERICA Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of Leicester By Brett Reinhold Lenz Department of Archaeology and Ancient History University of Leicester June 2011 1 DEDICATION This work is dedicated to Garreck, Haydn and Carver. And to Hank, for teaching me how rivers form. 2 Abstract This dissertation involves the development of a geologic framework applied to upper Pleistocene and earliest Holocene archaeological site discovery. It is argued that efforts to identify colonizer archaeological sites require knowledge of geologic processes, Quaternary stratigraphic detail and an understanding of basic soil science principles. An overview of Quaternary geologic deposits based on previous work in the region is presented. This is augmented by original research which presents a new, proposed regional pedostratigraphic framework, a new source of lithic raw material, the Beezley chalcedony, and details of a new cache of lithic tools with Paleoindian affinities made from this previously undescribed stone source. 3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The list of people who deserve my thanks and appreciation is large. First, to my parents and family, I give the greatest thanks for providing encouragement and support across many years. Without your steady support it would not be possible. Thanks Mom and Dad, Steph, Jen and Mellissa. To Dani and my sons, I appreciate your patience and support and for your love and encouragement that is always there. Due to a variety of factors, but mostly my own foibles, the research leading to this dissertation has taken place over a protracted period of time, and as a result, different stages of my personal development are likely reflected in it. -

Peut-On Dépasser L'alternative Entre Animaux Réels Et

Peut-on dépasser l’alternative entre animaux réels et animaux imaginaires? Pierre Lagrange To cite this version: Pierre Lagrange. Peut-on dépasser l’alternative entre animaux réels et animaux imaginaires?. Préten- taine, Prétentaine, 2016. halshs-02137380 HAL Id: halshs-02137380 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-02137380 Submitted on 23 May 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Peut-on dépasser l’alternative entre animaux réels et animaux imaginaires ? Pierre L AGRANGE ES HISTORIENS ONT une méthode pour Deux façons de parler des animaux parler des animaux imaginaires (dra- gons, licornes, sirènes). Méthode qui Malheureusement, ces deux méthodes sont irré- consiste à décrire la genèse de ces conciliables. La méthode qui permet d’étudier les créaturesL dans les cultures et l’imaginaire hu- animaux imaginaires ne permet pas de rendre mains, et les raisons pour lesquelles des gens ont compte des animaux réels car la frontière entre la pu, et peuvent encore parfois, y croire (1). réalité biologique et l’imaginaire culturel consti- tue une frontière hermétique, infranchissable. Les historiens ont aussi, depuis le grand livre de Comme le notait Jacques Le Goff dans sa célèbre Robert Delort, Les Animaux ont une histoire, étude sur le dragon de Saint Marcel : « Si le dra- publié en 1984 (2), une méthode pour parler des gon dont Saint Marcel a débarrassé les Parisiens a animaux réels. -

Searching for Sasquatch

SEARCHING FOR SASQUATCH 9780230111479_01_prexii.indd i 1/16/2011 5:40:31 PM PALGRAVE STUDIES IN THE HISTORY OF SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY James Rodger Fleming (Colby College) and Roger D. Launius (National Air and Space Museum), Series Editors This series presents original, high-quality, and accessible works at the cut- ting edge of scholarship within the history of science and technology. Books in the series aim to disseminate new knowledge and new perspectives about the history of science and technology, enhance and extend education, foster public understanding, and enrich cultural life. Collectively, these books will break down conventional lines of demarcation by incorporating historical perspectives into issues of current and ongoing concern, offering interna- tional and global perspectives on a variety of issues, and bridging the gap between historians and practicing scientists. In this way they advance schol- arly conversation within and across traditional disciplines but also to help define new areas of intellectual endeavor. Published by Palgrave Macmillan: Continental Defense in the Eisenhower Era: Nuclear Antiaircraft Arms and the Cold War By Christopher J. Bright Confronting the Climate: British Airs and the Making of Environmental Medicine By Vladimir Janković Globalizing Polar Science: Reconsidering the International Polar and Geophysical Years Edited by Roger D. Launius, James Rodger Fleming, and David H. DeVorkin Eugenics and the Nature-Nurture Debate in the Twentieth Century By Aaron Gillette John F. Kennedy and the Race to the Moon By John M. Logsdon A Vision of Modern Science: John Tyndall and the Role of the Scientist in Victorian Culture By Ursula DeYoung Searching for Sasquatch: Crackpots, Eggheads, and Cryptozoology By Brian Regal 9780230111479_01_prexii.indd ii 1/16/2011 5:40:31 PM Searching for Sasquatch Crackpots, Eggheads, and Cryptozoology Brian Regal 9780230111479_01_prexii.indd iii 1/16/2011 5:40:31 PM SEARCHING FOR SASQUATCH Copyright © Brian Regal, 2011. -

National Energy Board Office National De L’Énergie

NATIONAL ENERGY BOARD OFFICE NATIONAL DE L’ÉNERGIE Hearing Order OH-001-2014 Ordonnance d’audience OH-001-2014 Trans Mountain Pipeline ULC Trans Mountain Expansion Project Trans Mountain Pipeline ULC Projet d’agrandissement du réseau de Trans Mountain VOLUME 12 Hearing held at L’audience tenue à Coast Chilliwack Hotel 45920 First Avenue Chilliwack, British Columbia October 24, 2014 Le 24 octobre 2014 International Reporting Inc. Ottawa, Ontario (613) 748-6043 © Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada 2014 © Sa Majesté du Chef du Canada 2014 as represented by the National Energy Board représentée par l’Office national de l’énergie This publication is the recorded verbatim transcript Cette publication est un compte rendu textuel des and, as such, is taped and transcribed in either of the délibérations et, en tant que tel, est enregistrée et official languages, depending on the languages transcrite dans l’une ou l’autre des deux langues spoken by the participant at the public hearing. officielles, compte tenu de la langue utilisée par le participant à l’audience publique. Printed in Canada Imprimé au Canada HEARING ORDER/ORDONNANCE D’AUDIENCE OH-001-2014 IN THE MATTER OF Trans Mountain Pipeline ULC Application for the Trans Mountain Expansion Project HEARING LOCATION/LIEU DE L'AUDIENCE Hearing held in Chilliwack (British Columbia), Friday, October 24, 2014 Audience tenue à Chilliwack (Colombie-Britannique), vendredi, le 24 octobre 2014 BOARD PANEL/COMITÉ D'AUDIENCE DE L'OFFICE D. Hamilton Chairman/Président P. Davies Member/Membre A. Scott Member/Membre Transcript Hearing Order OH-001-2014 ORAL PRESENTATIONS/REPRÉSENTATIONS ORALES Hwlitsum First Nation Councillor Janice Wilson Dr. -

Historical Archaeology and the Importance of Material Things

HISTORICAL ARCHAEOLOGY AND THE IMPORTANCE OF MATERIAL THINGS LELAND FERGUSON, Editor r .\ SPECIAL PUBLICATION SERIES, NUMBER 2 Society for Historical Archaeology Special Publication Series, Number 2 published by The Society for Historical Archaeology The painting on the cover of this volume was adapted from the cover of the 1897 Sears Roebuck Catalogue, publishedby Chelsea House Publishers, New York, New York, 1968. The Society for Historical Archaeology OFFICERS RODERICK SPRAGUE, University ofIdaho President JAMES E. AYRES, Arizona State Museum President-elect JERVIS D. SWANNACK, Canadian National Historic Parks & Sites Branch Past president MICHAEL J. RODEFFER, Ninety Six Historic Site Secretary-treasurer JOHN D. COMBES, Parks Canada ,,,, , , Editor LESTER A. Ross, Canadian National Historic Parks & Sites Branch Newsletter Editor DIRECTORS 1977 KATHLEEN GILMORE, North Texas State University LEE H. HANSON, Fort Stanwix National Monument 1978 KARLIS KARKINS, Canadian National Parks & Sites Branch GEORGE QUIMBY, University ofWashington 1979 JAMES E.. FITTING, Commonwealth Associates,Inc. DEE ANN STORY, Balcones Research Center EDITORIAL STAFF JOHN D. COMBES ,, Editor Parks Canada, Prairie Region, 114 Garry Street, Winnipeg, Manitoba R3C IGI SUSAN JACKSON Associate Editor Institute of Archeology and Anthropology, University of South Carolina, Columbia, South Carolina 29208 JOHN L. COITER Recent Publications Editor National Park Service, 143South Third Street, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19106 WILLIAM D. HERSHEY , , Recent Publications Editor Temple University, Broad and Ontario, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19122 KATHLEEN GILMORE. ....................................................... .. Book Review Editor Institute for Environmental Studies, North Texas State University, Denton, Texas 76201 LESTER A. Ross Newsletter Editor National Historic Parks & Sites Branch, 1600Liverpool Court, Ottawa, Ontario, KIA OH4 R. DARBY ERD Art Institute of Archeology and Anthropology, University of South Carolina. -

Cultural Resources Report Cover Sheet

CULTURAL RESOURCES REPORT COVER SHEET Author: Noah Oliver and Corrine Camuso Title of Report: Cultural Resources Evaluations of Howard Carlin Trailhead Park, City of Cle Elum, Kittitas County, Washington Date of Report: May 2017 County: Kittitas Section: 27 Township: 20N Range: 15E Quad: Cle Elum Acres: 0.30 PDF of report submitted (REQUIRED) Yes Historic Property Export Files submitted? Yes No Archaeological Site(s)/Isolate(s) Found or Amended? Yes No TCP(s) found? Yes None Identified Replace a draft? Yes No Satisfy a DAHP Archaeological Excavation Permit requirement? Yes # No DAHP Archaeological Site #: Temp. HC-1 Submission of paper copy is required. Temp. HC-2 Please submit paper copies of reports unbound. Submission of PDFs is required. Please be sure that any PDF submitted to DAHP has its cover sheet, figures, graphics, appendices, attachments, correspondence, etc., compiled into one single PDF file. Please check that the PDF displays correctly when opened. Legal Description: T20N, R15E, Sec. 27 County: Kittitas USGS Quadrangle: Kittitas Total Project Acers: 0.30 Survey Coverage: 100% Sites and Isolates Identified: 1 Cultural Resources Evaluations of Howard Carlin Trailhead Park, City of Cle Elum, Kittitas County, Washington A report prepared for the City of Cle Elum By The Yakama Nation Cultural Resource Program Report prepared by: Noah Oliver and Corrine Camuso March 2017 Yakama Nation Cultural Resource Program Na-Mi-Ta-Man-Wit Nak-Nu-Wit Owt-Nee At-Tow Confederated Tribes and Bands of the Yakama Nation Post Office Box 151 Toppenish, WA 98948 ititamatpama´ Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................................... 1 Prehistoric Context ........................................................................................................................................ 3 Historic Context ........................................................................................................................................... -

Extreme Archaeology: the Resiilts of Investigations at High Elevation Regions in the Northwest

Extreme Archaeology: The Resiilts of Investigations at High Elevation Regions in the Northwest. by Rudy Reimer BA, Simon Fraser University, Burnaby, B.C. 1997 THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFLMENT OF TKE REQUIREhdENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of Archaeology @Rudy Reimer 2000 Simon Fraser University August 2ûûû Ail Rights Rese~ved.This work may not be reproduced in whole in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. uisitions and Acquisitions et '3B' iographic Senrices senfices bibfkgraphiques The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accord6 une licence non exclusive licence aliowiag the exclusive mettant A la National Liiof Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, lom, distribute or seli reproduire, prêter, distriiuer ou copies of ibis thesis in microfonn, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous papa or electronic formats. la finme de microfiche/fbn, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts hmit Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwjse de ceîie-ci ne doivent être imprimes reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. Review of ethnographie and ment archaeological studies suggest that past human use ofhigh elevation subalpine and alpine environments in northwestem North America was more intense than is currently believed. Archaeological survey high in coastai and interior mountain ranges resulted in iocating 21 archaeological sites ranging in age between 7,500-1,500 BP. -

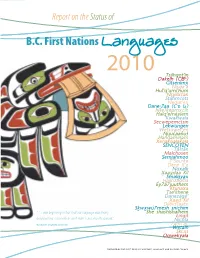

2010 Report on the Status of B.C First Nations Languages

Report on the Status of B.C. First Nations Languages 2010 Tsilhqot’in Dakelh (ᑕᗸᒡ) Gitsenimx̱ Nisg̱a’a Hul’q’umi’num Nsyilxcən St̓át̓imcets Nedut’en Dane-Zaa (ᑕᓀ ᖚ) Nłeʔkepmxcín Halq’eméylem Kwak̓wala Secwepemctsin Lekwungen Wetsuwet’en Nuučaan̓uɫ Hən̓q̓əm̓inəm̓ enaksialak̓ala SENĆOŦEN Tāłtān Malchosen Semiahmoo T’Sou-ke Dene K’e Nuxalk X̱aaydaa Kil Sm̓algya̱x Hailhzaqvla Éy7á7juuthem Ktunaxa Tse’khene Danezāgé’ X̱aad Kil Diitiidʔaatx̣ Sḵwx̱wú7mesh sníchim “…I was beginning to fear that our language was slowly She shashishalhem Łingít disappearing, especially as each Elder is put into the ground.” Nicola Clara Camille, secwepemctsin speaker Pəntl’áč Wetalh Ski:xs Oowekyala prepared by the First peoples’ heritage, language and Culture CounCil The First Peoples’ Heritage, Language and Culture Council (First We sincerely thank the B.C. First Nations language revitalization Peoples’ Council) is a provincial Crown Corporation dedicated to First experts for the expertise and input they provided. Nations languages, arts and culture. Since its formation in 1990, the Dr. Lorna Williams First Peoples’ Council has distributed over $21.5 million to communi- Mandy Na’zinek Jimmie, M.A. ties to fund arts, language and culture projects. Maxine Baptiste, M.A. Dr. Ewa Czaykowski-Higgins The Board and Advisory Committee of the First Peoples’ Council consist of First Nations community representatives from across B.C. We are grateful to the three language communities featured in our case studies that provided us with information on the exceptional The First Peoples’ Council Mandate, as laid out in the First Peoples’ language revitalization work they are doing. Council Act, is to: Nuučaan̓uɫ (Barclay Dialect) • Preserve, restore and enhance First Nations’ heritage, language Halq’emeylem (Upriver Halkomelem) and culture.