W S Let T E R

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Marlboro College

Potash Hill Marlboro College | Spring 2020 POTASH HILL ABOUT MARLBORO COLLEGE Published twice every year, Marlboro College provides independent thinkers with exceptional Potash Hill shares highlights of what Marlboro College community opportunities to broaden their intellectual horizons, benefit from members, in both undergraduate a small and close-knit learning community, establish a strong and graduate programs, are doing, foundation for personal and career fulfillment, and make a positive creating, and thinking. The publication difference in the world. At our campus in the town of Marlboro, is named after the hill in Marlboro, Vermont, where the college was Vermont, students engage in deep exploration of their interests— founded in 1946. “Potash,” or potassium and discover new avenues for using their skills to improve their carbonate, was a locally important lives and benefit others—in an atmosphere that emphasizes industry in the 18th and 19th centuries, critical and creative thinking, independence, an egalitarian spirit, obtained by leaching wood ash and evaporating the result in large iron and community. pots. Students and faculty at Marlboro no longer make potash, but they are very industrious in their own way, as this publication amply demonstrates. Photo by Emily Weatherill ’21 EDITOR: Philip Johansson ALUMNI DIRECTOR: Maia Segura ’91 CLEAR WRITING STAFF PHOTOGRAPHERS: To Burn Through Where You Are Not Yet BY SOPHIE CABOT BLACK ‘80 Emily Weatherill ’21 and Clement Goodman ’22 Those who take on risk are not those Click above the dial, the deal STAFF WRITER: Sativa Leonard ’23 Who bear it. The sign said to profit Downriver is how you will get paid, DESIGN: Falyn Arakelian Potash Hill welcomes letters to the As they do, trade around the one Later, further. -

Stories and Storytelling - Added Value in Cultural Tourism

Stories and storytelling - added value in cultural tourism Introduction It is in the nature of tourism to integrate the natural, cultural and human environment, and in addition to acknowledging traditional elements, tourism needs to promote identity, culture and interests of local communities – this ought to be in the very spotlight of tourism related strategy. Tourism should rely on various possibilities of local economy, and it should be integrated into local economy structure so that various options in tourism should contribute to the quality of people's lives, and in regards to socio-cultural identity it ought to have a positive effect. Proper treatment of identity and tradition surely strengthen the ability to cope with the challenges of world economic growth and globalisation. In any case, being what you are means being part of others at the same time. We enrich others by what we bring with us from our homes. (Vlahović 2006:310) Therefore it is a necessity to develop the sense of culture as a foundation of common identity and recognisability to the outer world, and as a meeting place of differences. Subsequently, it is precisely the creative imagination as a creative code of traditional heritage through intertwinement and space of flow, which can be achieved solely in a positive surrounding, that presents the added value in tourism. Only in a happy environment can we create sustainable tourism with the help of creative energy which will set in motion our personal aspirations, spread inspiration and awake awareness with the strength of imagination. Change is possible only if it springs from individual consciousness – „We need a new way to be happy” (Laszlo, 2009.). -

Stuy Hall to Begin Multi-Million Renovation Ohio Wesleyan Honors Memory of Alice Klund Levy, ‘32, Who Endowed $1 Million to University in Estate Gift

A TRUE COLLEGE NEWSPAPER TranscripTHE T SINCE 1867 Thursday, Oct. 29, 2009 Volume 148, No. 7 Stuy Hall to begin multi-million renovation Ohio Wesleyan honors memory of Alice Klund Levy, ‘32, who endowed $1 million to university in estate gift Phillips Hall vandalized By Michael DiBiasio Editor-in-Chief Graffiti was found inside and outside Phillips Hall Monday morning by an Ohio Wesleyan house- keeper with no sign of Photos provided courtesy of.... forced entry to the building, Left: Stuyvesant Hall shortly after it opened in 1931. Note the according to Public Safety. statue above the still-working white fountain. Public Safety Sergeant Above: Alice Klund Levy, pictured in this field hockey team photo in Christopher Mickens said the front row second from left, left a $1 million donation after her he is unsure whether the death in 2008, to be used for Stuy’s renovation. This will account markings found on chalk- for a considerable chunk of the planned restoration. boards, whiteboards, refrigerators and doors in By Mary Slebodnik have to use the money for a majored in politics and gov- ing her president of Mortar days and date nights because Phillips have any specific Transcript Reporter predetermined project or spe- ernment and French. She Board. normal heels echoed too loud- meaning. cific department. That deci- played field hockey along- According the 1932 edi- ly in the hallways. “Generally, such sym- A late alumna’s $1 million sion was left up to administra- side Helen Crider, whom the tion of “Le Bijou,” the cam- On Oct. 3-4, the board of bols represent the name of gift to the university might tors. -

TÍTERES EN PUERTO RICO, UNA PERPETUA Y ACOMPASADA EVOLUCIÓN Indice SEPTIEMBRE - DICIEMBRE / 2018

la hoja del titiritero / SEPTIEMBRE - DICIEMBRE / 2018 1 BOLETÍN ELECTRÓNICO DE LA COMISIÓN UNIMA 3 AMÉRICAS TERCERA ÉPOCA SEPTIEMBRE - DICIEMBRE03 / 2018 TÍTERES EN PUERTO RICO, UNA PERPETUA Y ACOMPASADA EVOLUCIÓN indIce SEPTIEMBRE - DICIEMBRE / 2018 ENCABEZADO DE BUENA FUENTE: 03 · Pinceladas puertorriqueñas Influencias de otros lares en la isla Dr. Manuel Antonio Morán 25 · Kamishibai-Puerto Rico Tere Marichal l boletín electrónico La Hoja LETRA CAPITAL del Titiritero, de la Comisión 04 · Las voces titiriteras de Suramérica Personalidades y agrupaciones del Unima 3 Américas, sale teatro de figuras en Puerto Rico con frecuencia cuatrienal, EN GRAN FORMATO · El Mundo de los Muñecos: con cierre los días 15 de · Breve panorama del teatro de títeres 28 40 años de alegría Eabril, agosto y diciembre. Las 07 en Puerto Rico 30 · Un titiritero llamado Mario Donate normas editoriales, teniendo en Dr. Manuel Antonio Morán cuenta el formato de boletín, son De festivales y publicaciones titiriteras de una hoja para las noticias e CUADRO DE TEXTOS en Puerto Rico informaciones, dos hojas para las entrevistas y tres hojas para los · Las huellas de la tempestad en el · Sobre la mesa. Una asignación (Acerca 11 31 artículos de fondo, investigaciones Corazón de Papel de Agua, Sol y Sereno del fenómeno de títeres para adultos en o reseñas críticas. De ser posible Cristina Vives Rodríguez Puerto Rico). Deborah Hunt acompañar los materiales con · Y No Había Luz antes 33 · La Titeretada: un festival independiente 14 imágenes. y después de María 34 · Otros festivales titiriteros · Papel Machete: el teatro de títeres y la · Algunas publicaciones de títeres en 16 Director lucha popular en Puerto Rico Puerto Rico Dr. -

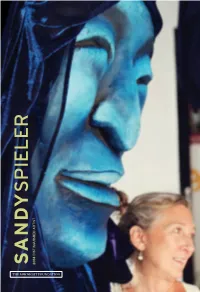

S and Y Spieler

SANDYSPIELER 2014 DISTINGUISHED ARTIST She changes form. She moves in between things and in between states, from liquid to solid to vapor: raindrop, snowflake, cloud. She orients. She refreshes. She transforms and sculpts everyone she encounters. She is a landmark and a route to follow. She quenches our thirst. We will not live without the lessons in which she continually involves us any more than we could live without water. TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION SHE MOVES LIKE WATER: When a MinnPost interviewer asked Sandy Spieler why she had chosen puppets as her medium, Sandy replied that “ DIVINING SANDY SPIELER HAVE NO PUPPETS COLLEEN SHEEHY 3 LIFE OF THEIR OWN, AND YET, WHEN YOU PICK THEM UP, A BREATH COMES INTO THEM. And then, when you lay them down, the breath goes THEATER OF HOPE out. It’s the ritual of life: We’re brought to our birth, then we move in our DAVID O’FALLON 18 life, then we lie down to the earth again.” For Sandy, such transformation is the very essence of art, and the transformation IN THE HEART OF THE CITY in which she specializes extends far beyond any single performance. She and her HARVEY M. WINJE 21 colleagues and her neighbors transform ideas into spectacle. They transform everyday materials like cardboard, sticks, fabric, and paper into figures that come to life. And through their art, Sandy and her collaborators at In the Heart of the Beast Puppet BIGGER THAN OURSELVES and Mask Theatre (HOBT) have helped transform their city and our region. Their PAM COSTAIN 25 work—which invites people in by traveling to where they live, learn, play, and work— combines arresting visuals, movement, and music to inspire us to be the caretakers of our communities and the earth. -

Filippino Lippi and Music

Filippino Lippi and Music Timothy J. McGee Trent University Un examen attentif des illustrations musicales dans deux tableaux de Filippino Lippi nous fait mieux comprendre les intentions du peintre. Dans le « Portrait d’un musicien », l’instrument tenu entre les mains du personnage, tout comme ceux représentés dans l’arrière-plan, renseigne au sujet du type de musique à être interprétée, et contribue ainsi à expliquer la présence de la citation de Pétrarque dans le tableau. Dans la « Madone et l’enfant avec les anges », la découverte d’une citation musicale sur le rouleau tenu par les anges musiciens suggère le propos du tableau. n addition to their value as art, paintings can also be an excellent source of in- Iformation about people, events, and customs of the past. They can supply clear details about matters that are known only vaguely from written accounts, or in some cases, otherwise not known at all. For the field of music history, paintings can be informative about a number of social practices surrounding the performance of music, such as where performances took place, who attended, who performed, and what were the usual combinations of voices and instruments—the kind of detail that is important for an understanding of the place of music in a society, but that is rarely mentioned in the written accounts. Paintings are a valuable source of information concerning details such as shape, exact number of strings, performing posture, and the like, especially when the painter was knowledgeable about instruments and performance practices, -

Rainer Ganahl: El Mundo Saturday, April 19Th – Saturday, May 24Th, 2014 Inaugural Opening Reception: April 19Th, from 7-9:30 Pm

April 1st, 2014 Pre-Opening Press Release Kai Matsumiya For Press inquiries: 153 ½ Stanton Street m. 617 678 4440 New York, New York 10002 w. 646 455 3588 www.kaimatsumiya.com [email protected] Gallery Hours: Tue-Sat: 12-8pm Rainer Ganahl: El Mundo Saturday, April 19th – Saturday, May 24th, 2014 Inaugural Opening Reception: April 19th, from 7-9:30 pm Kai Matsumiya is pleased to announce its inauguration with an exhibition of Rainer Ganahl’s El Mundo. The original project, an ad hoc, classical music performance, staged at the now-defunct El Mundo discount store, encapsulates the history of an East Harlem building as it passes through diverse incarnations that trace economic, demographic, and cultural shifts on both the local and global scene. Reflecting on the event, Ganahl writes: “Many opera pieces bring us back to politics, to emerging working-class cultures in which slaves and exploited people play a role, mirroring the industrialization of Europe in the 19th century with the rather under-privileged context in which El Mundo was built and functioned in Spanish Harlem.” The exhibition reenacts the event through photographs and film and runs from, Saturday, April 19th through May 24th. The space at 153 1⁄2 Stanton Street retains the left-over remains of the former tenant, Rocksmith, which sold merchandise from the Wu-tang clan among the other hip-hop retail items. The back space is graced with a genuine graffiti tag by “Mathematics”, the producer at Wu-Tang, and other remnants. Ganahl’s El Mundo piece at Kai Matsumiya will include a film projection of the live performance, and photographs of El Mundo. -

1109 SFBAPG Newsletter

September 2011 2011-2012 Board of Directors and Guild Officers President Art Gruenberger [email protected] 916-424-4736 The Gala is coming! Vice President Randall Metz [email protected] The Gala is coming! 510-569-3144 Treasurer Michael Nelson [email protected] 707-363-4573 Secretary Sharon Clay [email protected] 925-462-4518 Membership Officer Valerie Nelson [email protected] 707-363-4573 Newsletter Editor Talib Huff [email protected] 916-484-0606 Librarian Lee Armstrong [email protected] 707-996-9474 Conrad Bishop [email protected] 707-824-4307 In this issue: Lex Rudd th [email protected] • Latest News on the 50 Gala 626-224-8578 • Five Decades Ago - A Remembrance by Luman Jesse Vail Coad [email protected] 510-672-6900 • Pictures From the Meeting at Fairyland Webmaster • Memoir Reading Review Matt????? Baum • Cantastoria Festival Review [email protected] could be you! See inside for • Call For Webmaster details! • Calendar 1 SFBAPG 50th Celebration! Guild members, family and friends, past and present, are invited to join us for a GALA Event celebrating our Golden Anniversary. When: 6:30 pm, Saturday, September 24, 2011 Where: Uptown, 401 26th Street, Oakland, California What: Dinner & Golden Entertainment Tickets: $25.00 for guild members (past and present), $35.00 for non guild members (to ensure your spot, make get your tickets before September 9 Buy tickets online at http://www.brownpapertickets.com/event/193368 or send check made out to SFBAPG to Michael Nelson, Box 1258, Vallejo, CA 94590 (Ticket order forms should have come recently in your Guild Membership Renewal Package as well.) Questions? Email: [email protected] 6:30 - 7:30 Social hour, cocktails and pre-dinner entertainment - Tinker's Coin Productions in the personas of Tiberius the Touched and Gloriana Baccigalluppi will perform their version of "The Three Billy Goats Gruff." This Renaissance style show is filled with audience participation and lively action. -

ISTA 2019-2020 Artist in Residency (Air) Directory

ISTA 2019-2020 Artist in Residency (AiR) Directory www.ista.co.uk “This programme Welcome to the International Schools Theatre Association really helped (ISTA) Artist in Residency (AiR) directory for 2019-2020. my students in This is your ultimate guide to ISTA’s AiR programme and offers an extensive pool of 80 internationally acclaimed artists with a huge range of unique skills who are available to visit your school throughout the year. Like last year our aim has been preparing for to launch the directory as early as possible, to ensure that teachers and schools have the information as early as possible as budgets are set towards the second quarter of 2018. It is our hope that by doing this it gives you all the time you need to make bookings with the peace of mind that the decision hasn’t been their practical rushed. One of the beautiful things about this programme is that we’ll often have an assignments. They ISTA event in a town, city or country near you. If this is the case then it’s worth waiting to see which artists are attending that event and book them accordingly. This will save you money as the flights will have already been paid gained new ways for. Usually it’s just the internal travel you’d need to provide as well as the usual accommodation and meals etc. So enjoy reading through the profiles and use the index in the back of to approach their the directory to further narrow and ease your search. These pages should have all the information you need in order to bring amazing ISTA artists to your school, but if you do need more clarification or information then please do get work and left in touch. -

Uneven Resistance to Inequality in the Spaces of Food Labor and Urban Land Use Politics

MAPPING POWER RELATIONS IN THE ALTERNATIVE FOOD MOVEMENT: UNEVEN RESISTANCE TO INEQUALITY IN THE SPACES OF FOOD LABOR AND URBAN LAND USE POLITICS By JOSHUA SBICCA A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2014 1 © 2014 Joshua Sbicca 2 For Jennifer and human flourishing 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This dissertation is a collective product. While there were times when I felt like a lone wolf in the desert support in the form of critical feedback, encouragement, a hug, or a hot meal were readily and often supplied. In the first semester of graduate school, I took a seminar in Environmental Justice from Brian Mayer. Wanting to understand how people were fighting for environmental goods, I became enamored with the topic of food. No one in the department is a food scholar, but I received nothing but support from all those I encountered. Beginning with my master’s degree, Brian and Christine Overdevest were strong supporters of my work, and endorsed my qualitative project in the hopes this would feed into a dissertation. In addition, Stephen Perz always allowed my intellectual curiosities to guide me, partially because we share a wide view of environmentally related social science. Moreover, he offered regular constructive criticism and editing advice for my first two publications. I especially want to thank Whitney Sanford for requiring that we read Marx’s Ecology by John Bellamy Foster. This work proved to be a deep source of inspiration at a critical time in my graduate training. -

LAURA JEANETTE DULL Associate Professor, Secondary Education

LAURA JEANETTE DULL Associate Professor, Secondary Education EDUCATION Ph.D., 2003 New York University Humanities and Social Sciences in the Professions M.A., 1989 Teachers College Teaching Social Studies, NYS Certification Columbia University B.A., 1984 Hiram College History, magna cum laude, Phi Beta Kappa Additional Studies: 2010 Advanced Oral History Summer Institute, University of California, Berkeley 2006 Beginning Serbian Language, University of Novi Sad, Serbia 1993 Training course for law curriculum, Legal Outreach of New York 1991 Taft Seminar on Government, City University of New York 1991 Stock Market Game, New York Stock Exchange 1990 Japan: An Overview, Japan Society 1983 Hiram College Extramural Studies Program, Soviet Union 1982-1983 Institute of European Studies, Vienna, Austria Dissertation: “The Americans are coming”: Reverend Leon Sullivan’s Teachers for Africa Program in Peki, Ghana, Committee: Drs. P. Hosay, T. Moja and J. Zimmerman. PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE 2009-present Associate Professor, SUNY New Paltz (1.0) 2003-2009 Assistant Professor, SUNY New Paltz (1.0) 2002 Lecturer, SUNY New Paltz (1.0) 2001-2002 Mentor, New York City Public Schools (0.5) 2000-2001 Teachers for Africa Volunteer, Peki Training College, Ghana (1.0) 1997-2000 Graduate Teaching Fellow, New York University (.25) 1997-2000 Adjunct Instructor, Baruch College, NY, NY (.25) 1996-1997 Practitioner-in-Residence, William Paterson University, NJ (1.0) 1995-1996 Social Studies Teacher, Landmark High School, NY, NY (1.0) 1989-1995 Social Studies Teacher, Lower East Side Prep, NY, NY (1.0) Courses I developed at New Paltz: SED593: Teaching Democracy and Citizenship SED564: Reconstructing Social Studies Using Diverse Perspectives HON323: West African Histories and Perspectives SED593: You, Your Students, Your School, and the Property Tax, with Dr. -

Arts in Education Conference 2003 * September 12 - 14, 2003 Creativity & Collaboration

Arts in Education Conference 2003 * September 12 - 14, 2003 Creativity & Collaboration CONFERENCE WORKSHOPS The complete Arts in Education 2003 Conference Brochure is available on our website and includes the weekend's agenda, conference and workshop registration forms, plus room/meals reservation information. Saturday workshops will be filled on a first-come, first-served basis. Please make workshop choices on page 7 of the conference brochure. If you plan to attend any Friday workshops, please note your interest on your registration form. For additional information on AIE Roster Artists, please go to our website's on-line roster of artists at: http://www.state.nh.us/nharts/artsandartists/index.html Workshops run from 10 am to 4 pm, unless noted otherwise. For more information contact: Catherine O'Brian, NH State Council on the Arts, at 271-0795 or [email protected] or Frumie Selchen, Arts Alliance of Northern NH, at 323-7302 or [email protected]. Friday, September 12th "Meet the Artists" Share the Work Exhibits and Showcases Workshops: “From Idea to Successful Grant Award: An Introduction to Grantswriting,” 11 am - noon and then repeated, noon - 1 pm (bring your bag lunch). “Conscious Image: An Introduction to Cantastoria” with Bread & Puppet Theater artists, 11 am to 1:30 pm (bring your bag lunch). Please see also the Saturday workshop description below. Saturday, September 13th Workshops 1) Conscious Image: A Bread & Puppet Cantastoria Workshop, 10-4 Cantastoria (“to sing a story”), an ancient and useful way to tell a story with pictures, exists in many cultures. Bread & Puppet artists will teach a selection of the company’s own cantastoria and then create at least one cantastoria with workshop participants.