Theatrical Colloquia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FICTIONAL NARRATIVE WRITING RUBRIC 4 3 2 1 1 Organization

FICTIONAL NARRATIVE WRITING RUBRIC 4 3 2 1 1 The plot is thoroughly Plot is adequately The plot is minimally The story lacks a developed Organization: developed. The story is developed. The story has developed. The story plot line. It is missing either a interesting and logically a clear beginning, middle does not have a clear beginning or an end. The organized: there is clear and end. The story is beginning, middle, and relationship between the exposition, rising action and arranged in logical order. end. The sequence of events is often confusing. climax. The story has a clear events is sometimes resolution or surprise confusing and may be ending. hard to follow. 2 The setting is clearly The setting is clearly The setting is identified The setting may be vague or Elements of Story: described through vivid identified with some but not clearly described. hard to identify. Setting sensory language. sensory language. It has minimal sensory language. 3 Major characters are well Major and minor Characters are minimally Main characters are lacking Elements of Story: developed through dialogue, characters are somewhat developed. They are development. They are Characters actions, and thoughts. Main developed through described rather than described rather than characters change or grow dialogue, actions, and established through established. They lack during the story. thoughts. Main dialogue, actions and individuality and do not change characters change or thoughts. They show little throughout the story. grow during the story. growth or change during the story. 4 All dialogue sounds realistic Most dialogue sounds Some dialogue sounds Dialogue may be nonexistent, Elements of Story: and advances the plot. -

Marlboro College

Potash Hill Marlboro College | Spring 2020 POTASH HILL ABOUT MARLBORO COLLEGE Published twice every year, Marlboro College provides independent thinkers with exceptional Potash Hill shares highlights of what Marlboro College community opportunities to broaden their intellectual horizons, benefit from members, in both undergraduate a small and close-knit learning community, establish a strong and graduate programs, are doing, foundation for personal and career fulfillment, and make a positive creating, and thinking. The publication difference in the world. At our campus in the town of Marlboro, is named after the hill in Marlboro, Vermont, where the college was Vermont, students engage in deep exploration of their interests— founded in 1946. “Potash,” or potassium and discover new avenues for using their skills to improve their carbonate, was a locally important lives and benefit others—in an atmosphere that emphasizes industry in the 18th and 19th centuries, critical and creative thinking, independence, an egalitarian spirit, obtained by leaching wood ash and evaporating the result in large iron and community. pots. Students and faculty at Marlboro no longer make potash, but they are very industrious in their own way, as this publication amply demonstrates. Photo by Emily Weatherill ’21 EDITOR: Philip Johansson ALUMNI DIRECTOR: Maia Segura ’91 CLEAR WRITING STAFF PHOTOGRAPHERS: To Burn Through Where You Are Not Yet BY SOPHIE CABOT BLACK ‘80 Emily Weatherill ’21 and Clement Goodman ’22 Those who take on risk are not those Click above the dial, the deal STAFF WRITER: Sativa Leonard ’23 Who bear it. The sign said to profit Downriver is how you will get paid, DESIGN: Falyn Arakelian Potash Hill welcomes letters to the As they do, trade around the one Later, further. -

Fiction and the Theory of Action

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by White Rose E-theses Online Fiction and the Theory of Action A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Laurence Piercy School of English Literature, Language and Linguistics University of Sheffield May 2014 Abstract This thesis explores four mid-twentieth century fictional texts in relation to concepts of action drawn predominantly from Anglo-American analytic philosophy and contemporary psychology. The novels in question are Anna Kavan’s Ice, Samuel Beckett’s How It Is, Vladimir Nabokov’s Pale Fire and Malcolm Lowry’s Under the Volcano. The theory of action provides concepts, structures, and language to describe how agency is conceptualised at various levels of description. My exploration of these concepts in relation to fiction gives a framework for describing character action and the conceptualisation of agency in my primary texts. The theory of action is almost exclusively concerned with human action in the real world, and I explore the benefits and problems of transferring concepts from these discourses to literary criticism. My approach is focused around close reading, and a primary goal of this thesis is to provide nuanced analyses of my primary texts. In doing so, I emphasise the centrality of concepts of agency in fiction and provide examples of how action theory is applicable to literary criticism. i Table of Contents Abstract i Table of Contents ii Introduction 1 Chapter One -

Peter Schumann's Bread and Puppet Theater Barry Goldensohn

Masthead Logo The Iowa Review Volume 8 Article 32 Issue 2 Spring 1977 Peter Schumann's Bread and Puppet Theater Barry Goldensohn Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.uiowa.edu/iowareview Part of the Creative Writing Commons Recommended Citation Goldensohn, Barry. "Peter Schumann's Bread and Puppet Theater." The Iowa Review 8.2 (1977): 71-82. Web. Available at: https://doi.org/10.17077/0021-065X.2206 This Contents is brought to you for free and open access by Iowa Research Online. It has been accepted for inclusion in The oI wa Review by an authorized administrator of Iowa Research Online. For more information, please contact [email protected]. With disgust and contempt, Knowing the blood which the poet said Flowed with the earthly rhythm of desire a ... Was really river of disease no And the moon could longer Discover itself in the white flesh Because the body had gone Black in the crotch, And the mind itself a mere shadow of idea ... He opened the book again and again, Contemptuous, wanting to tear out The pages, wanting to hold the print, to His voice, the ugly mirror, Until the lyric and the rot Became indistinguishable, And the singing and the dying Became the same breath, under which He wished the poet the same fate, The same miserable fate. CRITICISM / BARRY GOLDENSOHN Peter Schumann's Bread and Puppet Theater was The Bread and Puppet Theater deeply involved with the civil rights is and anti-war protest movements and marked by their political moralism concern in two important respects: its with domestic issues, the home This is front, and its primitivism of technique and morality. -

The Civilians"

San Jose State University SJSU ScholarWorks Master's Theses Master's Theses and Graduate Research Spring 2012 A Versatile Group of Investigative Theater Practitioners: An Examination and Analysis of "The Civilians" Kimberly Suzanne Peterson San Jose State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/etd_theses Recommended Citation Peterson, Kimberly Suzanne, "A Versatile Group of Investigative Theater Practitioners: An Examination and Analysis of "The Civilians"" (2012). Master's Theses. 4158. DOI: https://doi.org/10.31979/etd.n3bg-cmnv https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/etd_theses/4158 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Master's Theses and Graduate Research at SJSU ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of SJSU ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A VERSATILE GROUP OF INVESTIGATIVE THEATER PRACTITIONERS: AN EXAMINATION AND ANALYSIS OF “THE CIVILIANS” A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of Theater Arts San José State University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts by Kimberly Peterson May 2012 © 2012 Kimberly Peterson ALL RIGHTS RESERVED The Designated Thesis Committee Approves the Thesis Titled A VERSATILE GROUP OF INVESTIGATIVE THEATER PRACTITIONERS: AN EXAMINATION AND ANALYSIS OF “THE CIVILIANS” by Kimberly Peterson APPROVED FOR THE DEPARTMENT OF THEATRE, RADIO-TELEVISION-FILM, ANIMATION & ILLUSTRATION SAN JOSÉ STATE UNIVERSITY May -

Stories and Storytelling - Added Value in Cultural Tourism

Stories and storytelling - added value in cultural tourism Introduction It is in the nature of tourism to integrate the natural, cultural and human environment, and in addition to acknowledging traditional elements, tourism needs to promote identity, culture and interests of local communities – this ought to be in the very spotlight of tourism related strategy. Tourism should rely on various possibilities of local economy, and it should be integrated into local economy structure so that various options in tourism should contribute to the quality of people's lives, and in regards to socio-cultural identity it ought to have a positive effect. Proper treatment of identity and tradition surely strengthen the ability to cope with the challenges of world economic growth and globalisation. In any case, being what you are means being part of others at the same time. We enrich others by what we bring with us from our homes. (Vlahović 2006:310) Therefore it is a necessity to develop the sense of culture as a foundation of common identity and recognisability to the outer world, and as a meeting place of differences. Subsequently, it is precisely the creative imagination as a creative code of traditional heritage through intertwinement and space of flow, which can be achieved solely in a positive surrounding, that presents the added value in tourism. Only in a happy environment can we create sustainable tourism with the help of creative energy which will set in motion our personal aspirations, spread inspiration and awake awareness with the strength of imagination. Change is possible only if it springs from individual consciousness – „We need a new way to be happy” (Laszlo, 2009.). -

Stuy Hall to Begin Multi-Million Renovation Ohio Wesleyan Honors Memory of Alice Klund Levy, ‘32, Who Endowed $1 Million to University in Estate Gift

A TRUE COLLEGE NEWSPAPER TranscripTHE T SINCE 1867 Thursday, Oct. 29, 2009 Volume 148, No. 7 Stuy Hall to begin multi-million renovation Ohio Wesleyan honors memory of Alice Klund Levy, ‘32, who endowed $1 million to university in estate gift Phillips Hall vandalized By Michael DiBiasio Editor-in-Chief Graffiti was found inside and outside Phillips Hall Monday morning by an Ohio Wesleyan house- keeper with no sign of Photos provided courtesy of.... forced entry to the building, Left: Stuyvesant Hall shortly after it opened in 1931. Note the according to Public Safety. statue above the still-working white fountain. Public Safety Sergeant Above: Alice Klund Levy, pictured in this field hockey team photo in Christopher Mickens said the front row second from left, left a $1 million donation after her he is unsure whether the death in 2008, to be used for Stuy’s renovation. This will account markings found on chalk- for a considerable chunk of the planned restoration. boards, whiteboards, refrigerators and doors in By Mary Slebodnik have to use the money for a majored in politics and gov- ing her president of Mortar days and date nights because Phillips have any specific Transcript Reporter predetermined project or spe- ernment and French. She Board. normal heels echoed too loud- meaning. cific department. That deci- played field hockey along- According the 1932 edi- ly in the hallways. “Generally, such sym- A late alumna’s $1 million sion was left up to administra- side Helen Crider, whom the tion of “Le Bijou,” the cam- On Oct. 3-4, the board of bols represent the name of gift to the university might tors. -

Building on a Legacy of Creativity

Building on a Legacy of Creativity: UNDERSTANDING AND EXPANDING THE CREATIVE ECONOMY OF THE NORTHEAST KINGDOM A Report to the Vermont Arts Council and the Vermont Creative Network Prepared by Melissa Levy, Community Roots Michael Kane Stuart Rosenfeld Stephen Michon, FutureWorks Julia Dixon December 21, 2018 This publication is the result of tax-supported funding from the USDA, Rural Development, and as such is not copyrightable. It may be reprinted with the customary crediting of the source. Funding for this project was also provided by the Vermont Community Foundation 2 Acknowledgements This report was prepared for the Vermont Arts Council and the Vermont Creative Network by a team of consultants working through Community Roots, LLC. The team consisted of Michael Kane, Michael Kane Consulting; Stuart Rosenfeld, formerly with RTS, Inc.; Melissa Levy, Community Roots; Julia Dixon; and Stephen Michon, formerly with FutureWorks. The report was co-authored by Kane, Levy, Rosenfeld, and Dixon. Pamela Smith copyedited and formatted the initial draft report. The primary sources of funding were grants from USDA Rural Development, the Vermont Community Foundation, and the Vermont Arts Council. The team worked closely with Amy Cunningham, Vermont Arts Council and Jody Fried, Catamount Arts. They helped the team understand the region, identified key individuals and companies, made the contacts needed to gather information, and generally supported the research process. Amy organized the Advisory Committee meetings and played a major role in organizing focus groups. The members of the Advisory Committee, which met three times and offered feedback at crucial junctures in the process were: • Scott Buckingham, Friends of Dog Mountain • Jennifer Carlo, Circus Smirkus • Evan Carlson, Lyndon Economic Development Task Force • Ben Doyle, USDA Rural Development • Ceilidh Galloway-Kane, WonderArts • Patrick Guckin, St. -

TÍTERES EN PUERTO RICO, UNA PERPETUA Y ACOMPASADA EVOLUCIÓN Indice SEPTIEMBRE - DICIEMBRE / 2018

la hoja del titiritero / SEPTIEMBRE - DICIEMBRE / 2018 1 BOLETÍN ELECTRÓNICO DE LA COMISIÓN UNIMA 3 AMÉRICAS TERCERA ÉPOCA SEPTIEMBRE - DICIEMBRE03 / 2018 TÍTERES EN PUERTO RICO, UNA PERPETUA Y ACOMPASADA EVOLUCIÓN indIce SEPTIEMBRE - DICIEMBRE / 2018 ENCABEZADO DE BUENA FUENTE: 03 · Pinceladas puertorriqueñas Influencias de otros lares en la isla Dr. Manuel Antonio Morán 25 · Kamishibai-Puerto Rico Tere Marichal l boletín electrónico La Hoja LETRA CAPITAL del Titiritero, de la Comisión 04 · Las voces titiriteras de Suramérica Personalidades y agrupaciones del Unima 3 Américas, sale teatro de figuras en Puerto Rico con frecuencia cuatrienal, EN GRAN FORMATO · El Mundo de los Muñecos: con cierre los días 15 de · Breve panorama del teatro de títeres 28 40 años de alegría Eabril, agosto y diciembre. Las 07 en Puerto Rico 30 · Un titiritero llamado Mario Donate normas editoriales, teniendo en Dr. Manuel Antonio Morán cuenta el formato de boletín, son De festivales y publicaciones titiriteras de una hoja para las noticias e CUADRO DE TEXTOS en Puerto Rico informaciones, dos hojas para las entrevistas y tres hojas para los · Las huellas de la tempestad en el · Sobre la mesa. Una asignación (Acerca 11 31 artículos de fondo, investigaciones Corazón de Papel de Agua, Sol y Sereno del fenómeno de títeres para adultos en o reseñas críticas. De ser posible Cristina Vives Rodríguez Puerto Rico). Deborah Hunt acompañar los materiales con · Y No Había Luz antes 33 · La Titeretada: un festival independiente 14 imágenes. y después de María 34 · Otros festivales titiriteros · Papel Machete: el teatro de títeres y la · Algunas publicaciones de títeres en 16 Director lucha popular en Puerto Rico Puerto Rico Dr. -

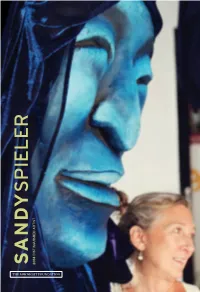

S and Y Spieler

SANDYSPIELER 2014 DISTINGUISHED ARTIST She changes form. She moves in between things and in between states, from liquid to solid to vapor: raindrop, snowflake, cloud. She orients. She refreshes. She transforms and sculpts everyone she encounters. She is a landmark and a route to follow. She quenches our thirst. We will not live without the lessons in which she continually involves us any more than we could live without water. TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION SHE MOVES LIKE WATER: When a MinnPost interviewer asked Sandy Spieler why she had chosen puppets as her medium, Sandy replied that “ DIVINING SANDY SPIELER HAVE NO PUPPETS COLLEEN SHEEHY 3 LIFE OF THEIR OWN, AND YET, WHEN YOU PICK THEM UP, A BREATH COMES INTO THEM. And then, when you lay them down, the breath goes THEATER OF HOPE out. It’s the ritual of life: We’re brought to our birth, then we move in our DAVID O’FALLON 18 life, then we lie down to the earth again.” For Sandy, such transformation is the very essence of art, and the transformation IN THE HEART OF THE CITY in which she specializes extends far beyond any single performance. She and her HARVEY M. WINJE 21 colleagues and her neighbors transform ideas into spectacle. They transform everyday materials like cardboard, sticks, fabric, and paper into figures that come to life. And through their art, Sandy and her collaborators at In the Heart of the Beast Puppet BIGGER THAN OURSELVES and Mask Theatre (HOBT) have helped transform their city and our region. Their PAM COSTAIN 25 work—which invites people in by traveling to where they live, learn, play, and work— combines arresting visuals, movement, and music to inspire us to be the caretakers of our communities and the earth. -

The Erinyes in Aeschylus' Oresteia

The Erinyes in Aeschylus’ Oresteia Cynthia Werner A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Victoria University of Wellington (2012) ABSTRACT This dissertation explores the Erinyes’ nature and function in Aeschylus’ Oresteia. It looks at how Aeschylus conceives the Erinyes, particularly their transformation into Semnai Theai, as a central component of the Oresteia’s presentation of social, moral and religious disorder and order. The dissertation first explores the Erinyes in the poetic tradition, then discusses the trilogy’s development of the choruses, before examining the Erinyes’ / Semnai Theai’s involvement in the trilogy’s establishment of justice and order and concluding with an analysis of why Aeschylus chooses Athens (over Argos and Delphi) as the location for trilogy’s decision making and resolution. Chapter One explores the pre-Aeschylean Erinyes’ origin and primary associations in order to determine which aspects of the Erinyes / Semnai Theai are traditional and how Aeschylus innovates in the tradition. It further identifies epithets and imagery that endow the Erinyes / Semnai Theai with fearsome qualities, on the one hand, and with a beneficial, preventive function, on the other. The discussion of the development of the choruses throughout the trilogy in Chapter Two takes three components: an examination of (1) the Erinyes’ transformation from abstract goddesses to a tragic chorus, (2) from ancient spirits of vengeance and curse to Semnai Theai (i.e. objects of Athenian cult) and (3) how the choruses of Agamemnon and Choephori prefigure the Erinyes’ emergence as chorus in Eumenides. Of particular interest are the Argive elders’ and slave women’s invocations of the Erinyes, their action and influence upon events, and their uses of recurrent moral and religious ideals that finally become i an integral part of the Areopagus and the cult of the Semnai Theai. -

Peter Schumann the Shatterer Nov 9 2013 Mar 30 2014

Peter Nov 9 Schumann 2013 The Mar 30 Shatterer 2014 Uncertain mind’s black and white language tries to cope with the Peter progressive dirt of problems. The dirt sticks, the landscape thickens, the clouds are full of surprise attacks, combatants enter the scene, Schumann stormworn feet scramble into rescue positions, the 3 categories of accelerated man (vertical, horizontal & diagonal), their architecture The twisted from excessive speed, fall from the processed sky that contains Shatterer their brain, into the shabby downbelow. The shatterer show presents shattered worlds confronted by the 99% giant and flag waver of the peasant boot flag, which his 15th century peasant colleagues raised against the capitalism of their day. Nov 9 The shatterer theme is from a) my nazi childhood, when worldshattering was the law of the land, & b) from Oppenheimer’s famous BhagavadGita 2013 quote (I am become death, the shatterer of worlds) at the occasion of the Mar 30 1st atomic bomb explosion. 2014 —Peter Schumann Peter Schumann was born in Silesia, Germany in 1934 and relocated to the United States in 1961. In 1963 on Manhattan’s Lower East Side, he founded the Bread and Puppet Theater, which presented numerous free indoor and outdoor performances throughout New York during the 1960s before moving to Vermont in 1970, where members of the theater continue to reside. Cover: Peter Schumann, The Shatterer (detail). Schumann’s background in dance and sculpture coupled with his Queens Museum, 2013. upbringing during the Second World War heavily informed the mission of This exhibition is curated by Jonathan Berger the theater.