HMG Scholarships Cluster Review March 2014

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

International Resources List

International Resources List As an international student interested in attending Columbia School of Social Work, you should expect to have sufficient funding to finance the entire course of study. This handout contains information on government agencies, private organizations, publications and websites that might provide a way to locate funding. This is not a Recommended or Preferred Lender List. This is a simply list of international resources that has been collected based on current and former student experience (shared with us by Columbia Business School colleagues), as well as SW staff scouring the internet for various resouces that offer funding or opportunities to international students. Students have the right and ability to select the lender of their choice and are not required to use any of the resources on this list. NOTE: The information provided below is NOT an endorsement of any organization or scholarship program. The below is being provided for informational purposes only. All students: International Search Engines: Institute of International Education (IIE): IIE, which seeks to foster educational exchange, has great resources for international students. International Education Financial Aid (IEFA): IEFA is the premier resource for financial aid, college scholarship, and grant information for US and international students wishing to study abroad. At this site, you will find the most comprehensive college scholarship search and grant listings, plus international student loan programs and other information to promote study abroad. International Research and Exchanges Board: IREX administers various fellowships for non-degree studies as well as one- and two-year graduate degree studies in the US for foreign nationals within 11 areas of study. -

Scholarships & Fellowships for International Students

Scholarships & Fellowships for International Students AAMC Financing Your Medical Education https://www.aamc.org/what-we-do/aamc-awards A series of grants and awards honoring individuals in the fields of medical education, research, and community service. Deadlines vary. AIA / AAF Minority/Disadvantaged Scholarship http://www.aia.org/education/AIAB081881 Grants ranging from $500-$2,500 for high school seniors and first-years who intend to pursue a NAAB-accredited professional degree (5-year BA or BA + MA) in architecture. Applicants must be legal residents of the United States. Deadline TBD. Albright Institute Fellowships http://www.aiar.org/available-fellowships/ A grant of up to $325,000 in fellowships and awards to 32 recipients who will live at the Albright Institute and study a specific field in archaeology. In addition, 32 Associate Fellows including Senior, Post-Doctoral, and Research Fellows receive funding from other sources. Deadlines vary. Alexander Graham Bell Association for the Deaf and Hard of Hearing http://listeningandspokenlanguage.org/Tertiary.aspx?id=2102 Students who were diagnosed with hearing loss before the age of seven are eligible for a merit-based scholarship ranging from $1,000-$10,000. Deadline March. Allen Lee Hughes Fellowship https://www.arenastage.org/education/fellows-and-interns/ Individuals interested in artistic and technical production, arts administration and community engagement. Fellowship provides a modest stipend and is intended to increase participation of people of color in the arts. Deadline March (summer); April (season). Amelia Earhart Fellowships (Zonta International Foundation) http://www.zonta.org/WhatWeDo/InternationalPrograms/AmeliaEarhartFellowship.aspx Women of any nationality with a superior academic record and a bachelor's degree in science or engineering. -

Trusts and Organisations Offering Scholarships to International Students

Trusts and organisations offering scholarships to international students Below you will find a list of trusts and organizations that award various scholarships to international students. If you are ineligible for a Canon Collins Trust scholarship please look at the options below. Please do not contact Canon Collins Trust regarding queries about these scholarships. The following websites are useful for searching for relevant scholarships: - http://scholarship-positions.com/scholarship-for-south-african-students/2012/05/08/ - http://www.scholarship-search.org.uk/ - http://www.advance-africa.com/Scholarships-and-Grants.html - http://www.educationuk.org/UK/Applications/Scholarships-for-UK-study/scholarships-for-international- postgraduate-students - http://www.soas.ac.uk/registry/scholarships/ - http://www.africadesk.ac.uk/pages/funding/scholarship - http://scholarship-positions.com/scholarships-for-african-students-in-uk/ - http://www.scholars4dev.com/category/target-group/africans-scholarships/ - http://www.european-funding-guide.eu/ For general information about studying in the UK visit: - http://www.ukcisa.org.uk/student/fees_student_support.php - http://www.postgraduatestudentships.co.uk/subject/all-subjects/pgt African Palliative Care Nurses Scholarship Fund Provides a limited number of scholarships each year for Palliative Care Training opportunities for nurses. Web: http://www.africanpalliativecare.org/index.php?option=c Scholarships are awarded up to a maximum of US$ 4,000 om_content&view=article&id=159 through a competitive application process once a year. APCA and FHSSA give priority to requests of Registered and Enrolled nurses to pursue formal palliative care training in Africa. They are also willing to potentially consider one scholarship for a distance Learning Masters programme, when necessary for the career objective of the student (i.e. -

Information Sheet Adapted From

Marshall Scholarship Information Sheet Adapted from http://www.marshallscholarship.org NOTE FOR INTERNATIONAL STUDENTS: Notre Dame students and alumni who are not citizens of the U.S. might consider the Chevening Scholarship. Please visit http://www.chevening.org for more information and contact CUSE National Fellowships at [email protected] so that we can discuss the application process. What is the Marshall Scholarship? The purpose of the Marshall Scholarship, funded by the Foreign and Commonwealth Office of the British government, is to finance young Americans of high ability to study for a degree in the United Kingdom. The award covers tuition, fees, and a generous stipend. Typically, the award lasts for two years, but a limited number of one-year scholarships are awarded. Also, a third-year extension is available for the two-year Marshall in certain cases. Note that the Marshall does not fund undergraduate degrees, the MBA, the MSc/MFE in Financial Economics, the MSc in Global Health Science, the MPP at the University of Oxford, professional degrees, or degrees that require extended periods away from the university or the UK. Who is eligible? Marshall Scholarship applicants must be U.S. citizens and: 1. Hold a first degree from a four-year college or university in the US by the time the Scholarship would begin. The degree must have been awarded no later than the April of two years prior to the application year. (So if one is applying in 2016, the first degree must be awarded between April 2014 and August 2017.) 2. Have a minimum GPA of 3.7, with exceptions in very rare cases. -

Scholarships That Accept Applications from International Students

Scholarships that Accept Applications from International Students AAMC Financing Your Medical Education www.aamc.org/students/financing/start.htm A series of programs to assist students in managing loans and preparing for future financial stability within the Medical field. Deadlines variable. AIA / AAF Minority/Disadvantaged Scholarship http://www.aia.org/education/AIAB081881 Grants ranging from $500-$2,500 for high school seniors and first-years who intend to pursue a NAAB-accredited professional degree (5-year BA or BA + MA) in architecture. Applicants must be legal residents of the United States. Deadline: mid-April. Albright Institute Fellowships http://www.aiar.org/fellowships.html A grant of up to $325,000 in fellowships and awards to 32 recipients who will live at the Albright Institute and study a specific field in archaeology. In addition, 32 Associate Fellows including Senior, Post-Doctoral, and Research Fellows receive funding from other sources. Deadlines variable. Alexander Graham Bell Association for the Deaf and Hard of Hearing http://nc.agbell.org/NetCommunity/Page.aspx?pid=493 Students who were diagnosed with hearing loss before the age of seven are eligible for a merit-based scholarship ranging from $1,000-$10,000. Deadline: mid-March. Allen Lee Hughes Fellowship http://www.arenastage.org/education/education-programs/internships-fellowships/ Individuals interested in artistic and technical production, arts administration and community engagement. Fellowship provides a modest stipend and is intended to increase participation of people of color in the arts. Deadline: mid-March (summer), mid-April (season). All-USA College Academic Team http://www.usatoday.com/news/education/2002-11-04-allstars_x.htm?Loc=vanity Recognition program for exceptional full-time undergraduates at four-year institutions in the USA and its territories. -

Trusts and Organisations Offering Scholarships to International Students

Trusts and organisations offering scholarships to international students Below you will find a list of trusts and organizations that award various scholarships to international students. If you are ineligible for a Canon Collins Trust scholarship please look at the options below. Please do not contact Canon Collins Trust regarding queries about these scholarships. The following websites are useful for searching for relevant scholarships: - http://www.internationalscholarships.dhet.gov.za/scholarships.html - http://scholarship-positions.com/scholarship-for-south-african-students/2012/05/08/ - http://www.scholarship-search.org.uk/ - http://www.advance-africa.com/Scholarships-and-Grants.html - http://www.educationuk.org/UK/Applications/Scholarships-for-UK-study/scholarships-for-international- postgraduate-students - http://www.soas.ac.uk/registry/scholarships/ - http://www.africadesk.ac.uk/pages/funding/scholarship - http://scholarship-positions.com/scholarships-for-african-students-in-uk/ - http://www.scholars4dev.com/category/target-group/africans-scholarships/ - http://www.european-funding-guide.eu/ For general information about studying in the UK visit: - http://www.postgraduatestudentships.co.uk/subject/all-subjects/pgt - http://www.ukcisa.org.uk/student/fees_student_support.php African Palliative Care Nurses Scholarship Fund Provides a limited number of scholarships each year for Palliative Care Training opportunities for nurses. Web: http://www.africanpalliativecare.org/index.php?option=c Scholarships are awarded up to a maximum of US$ 4,000 om_content&view=article&id=159 through a competitive application process once a year. APCA and FHSSA give priority to requests of Registered and Enrolled nurses to pursue formal palliative care training in Africa. They are also willing to potentially consider one scholarship for a distance Learning Masters programme, when necessary for the career objective of the student (i.e. -

Outside International Scholarship List & Application

OPPORTUNITIES FOR INTERNATIONAL STUDENTS Scholarship Scholarship Name & Contact Website Organization Description AAUW Educational Fellowships will be awarded to graduate AAUW Educational Foundation International female foreign students of outstanding Foundation http://www.aauw.org/education/fga/fellowships_gra Fellowships ability who can be expected to give Dept. 60 nts/international.cfm effective leadership in their fields upon 301 ACT Drive return to their home country. Iowa City, IA 52243- 4030 ADAMHA National PhD in areas of biomedical & behavioral Westwood Bldg #240, Research Service research within one of the three NIH http://www.granst1.nih.gov/grants Awards institutes. Bethesda, MD 20892 ph: 301-594-7248 AEI Scholarship Fund Scholarships to female medical students Society Bank 10 South Main St. Ann Arbor, MI 48104 ph: 313-994-5555 African-American 833 United Nations Institute Plaza New York, N.Y. 10017 Agency for Health Care Grants for Dissertation Research. For Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality students in the social, medical, Research and Quality http://www.ahrq.gov/ management or health sciences. Grants Management 540 Gaither Road, Suite 4000 Rockville, MD 20850 Alexander Graham Bell Administering various awards for 3417 Volta Place, NW Association for the Deaf auditory-oral students who a) were born Washington, D.C. http://www.agbell.org/ with profound hearing losses, or b) 20007 experienced a severe hearing loss before acquiring language. Applicants must enroll in a college or university program that primarily enrolls students with normal hearing. American Antiquarian Dissertation fellowships for conducting 185 Salisbury St. Society research using AAS library's resources. Worcester, MA 01609 http://www.americanantiquarian.org/ ph: 508-752-5221 American Association for 10 weeks summer fellowships at the 1333 H St. -

HMG Scholarships Cluster Review March 2015

HMG Scholarships Cluster Review March 2015 The review was conducted by: Amanda Spielman, Chair of Ofqual. 1 Contents Executive Summary 3 Recommendations 6 Context, Purpose and Scope 9 Rationale 12 Implementation 16 Scheme Descriptions 21 Scheme Allocation 27 Scheme Oversight 31 Scheme Phases 33 Scheme Finances 38 Annexes 45 A – Terms of Reference 46 B – 2013 Triennial Review of CSC - Recommendations 48 C – 2013 Triennial Review of MACC - 50 Recommendations D – 2014 Internal Review of the Chevening 52 Programme - Recommendations E – Commonwealth Scholarship Scheme Overview 54 F – Marshall Scholarship Scheme Overview 55 G – Chevening Scholarship Programme Overview 56 H – Newton Fund Overview 57 I – Chevening Administration Cost Efficiencies – 59 note prepared by ACU J – Scholarship Country Coverage 62 K – Stakeholders Consulted 67 2 Scholarships Cluster Review Executive Summary Context This cluster review follows the individual triennial reviews of the two scholarship non- departmental public bodies(NDPB), the Commonwealth Scholarship Commission (CSC) and the Marshall Aid Commemoration Commission (MACC), as well as an internal review by the FCO of the Chevening scholarship scheme. Its aim was to find whether there is scope for further efficiencies and synergies, and if so what structure, administration or delivery might realise those improvements. Scholarship schemes build soft power, in the short and long term; they promote international development; they enhance the reputation of UK universities; they recognise and promote the highest standards of intellectual achievement; they build international academic communities; they recognise and promote the highest standards of intellectual achievement; and they project British excellence abroad, promoting the UK internationally as a place to visit, study and do business. -

2019-2020 Deadlines

2019 - 2020 Deadlines Campus Deadline National Deadline Fellowship (one month prior to National deadlines, unless otherwise noted) Fall Term Winter Break Winter Term Spring Term Summer American Australian Association Scholarship October 15, 2019 (US to Australia Graduate Scholarships) American India Foundation Clinton Fellowship December 2019 Ashley Soule Conroy June 1, 2020 (Fall Term Abroad) Ashley Soule Conroy October 1, 2019 (Winter and/or Spring Term Abroad) Priority: February 2020 Biological Discovery in Woods Hole Summer Opportunity for Undergraduate Research Final: March 2020 Blakemore Freeman Fellowship December 30, 2019 (an academic year of advanced level language study in East or 5:00 PM (Pacific) Southeast Asia) January 30, 2020 Boren Fellowship (grad program) 5:00 PM (Eastern) February 5, 2020 Boren Scholarship (undergrad program) 5:00 PM (Eastern) Bridging Scholarship - Fall & full year April/May 2020 November 5, 2019 Chevening Scholarship 12:00 (Greenwich Mean Time) Christianson Grant October 15, 2019 March 15, 2020 July 15, 2020 January 2020 Clarendon Scholarships (Varies by Course) Congress-Bundestag Youth Exchange for Young Professionals December 2019 (CBYX) Coro Fellowship in Public Affairs Early January 2020 Critical Language Scholarship (CLS) November 2019 Cultural Ambassadors: North American Language and Culture Mid April 2020 Assistants in Spain DAAD EMGIP (Émigré Memorial German Internship Program)– September 15, 2019 Bundestag November 4, 2019 DAAD Research - One Year Grant 5:00 PM November 4, 2019 DAAD Study -

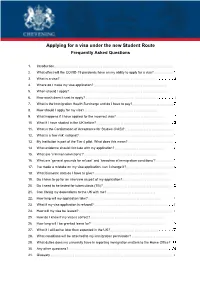

Applying for a Visa Under the New Student Route Frequently Asked Questions

Applying for a visa under the new Student Route Frequently Asked Questions 1. Introduction 2. What effect will the COVID-19 pandemic have on my ability to apply for a visa? 3. What is a visa? 4. Where do I make my visa application? 5. When should I apply? 6. How much does it cost to apply? 7. What is the Immigration Health Surcharge and do I have to pay? 8. How should I apply for my visa? 9. What happens if I have applied for the incorrect visa? 10. What if I have studied in the UK before? 11. What is the Confirmation of Acceptance for Studies (CAS)? 12. What is a ‘low risk’ national? 13. My institution is part of the Tier 4 pilot. What does this mean? 14. What evidence should I include with my application? 15. What are ‘criminal convictions’? 16. What are ‘general grounds for refusal’ and ‘breaches of immigration conditions’? 17. I’ve made a mistake on my visa application, can I change it? 18. What biometric data do I have to give? 19. Do I have to go for an interview as part of my application? 20. Do I need to be tested for tuberculosis (TB)? 21. Can I bring my dependants to the UK with me? 22. How long will my application take? 23. What if my visa application is refused? 24. How will my visa be issued? 25. How do I know if my visa is correct? 26. How long will I be granted leave for? 27. What if I will arrive later than expected in the UK? 28. -

Scholarships for International Students

AAMC Financing Your Medical Education https://www.aamc.org/students/applying/requirements/msar/toolkit/177064/financing_ your_medical_education.html A series of programs to assist students in managing loans and preparing for future financial stability within the Medical field. AAMC Medical Scientist Training Program https://www.aamc.org/students/research/mdphd/ Grants made available of varying quantities in all the sciences. AlA I AAF Minority Disadvantaged Scholarship http://www.scholarships.com/financial-aid/college-scholarships/scholarships-by- type/minority-scholarships/african-american-scholarships/aia-aaf-minority- disadvantaged-scholarship/ Grants ranging from $500-$2,500 for high school seniors and first-years. Albright Institute Fellowships http://www.aiar.org/fellowships.html A grant of up to $252,000 for students who will live at the Albring Institute and study a specific field in archaeology. Allen Lee Hughes Fellowship http://www.arenastage.org/education/education-programs/internships-fellowships/ Individuals interested in artistic and technical production, arts administration and community engagement. Fellowship provides a modest stipend and is intended to increase participation of people of color in the arts. All-USA College Academic Team http://ihouse.ucsd.edu/Scholarships and Funding/funding-scholarships.html Recognition program for exceptional full-time undergraduates at four-year institutions in the USA and its territories, American Center of Oriental Research Scholarships and Fellowships http://www.bu.edu/acor/fellowsh.htm -

Applying for a Tier 4 Student Visa Frequently Asked Questions

Applying for a Tier 4 student visa Frequently Asked Questions 1. What effect will the COVID-19 pandemic have on my ability to apply for a visa? ........................ 2 2. What is a visa? ....................................................................................................................................... 2 3. Where do I make my visa application? ............................................................................................... 2 4. When should I apply? ............................................................................................................................ 2 5. How much does it cost to apply? ......................................................................................................... 2 6. What is the Immigration Health Surcharge and do I have to pay? ................................................. 3 7. How should I apply for my visa? .......................................................................................................... 3 8. What happens if I have applied for the incorrect visa? .................................................................... 3 9. What if I have studied in the UK before? ............................................................................................ 3 10. What is the Confirmation of Acceptance for Studies (CAS)? .......................................................... 3 11. What is a ‘low risk’ national? ...............................................................................................................