Tailored Review of the Marshall Aid Commemoration Commission (MACC)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rules for Candidates Wishing to Apply for a Two Year

GENERAL 2022 1. Up to fifty Marshall Scholarships will be awarded in 2022. They are tenable at any British university and for study in any discipline at graduate level, leading to the RULES FOR CANDIDATES WISHING TO award of a British university degree. Conditions APPLY FOR A TWO YEAR MARSHALL governing One Year Scholarships are set out in a SCHOLARSHIP ONLY. separate set of Rules. Marshall Scholarships finance young Americans of high 2. Candidates are invited to indicate two preferred ability to study for a degree in the United Kingdom in a universities, although the Marshall Commission reserves system of higher education recognised for its excellence. the right to decide on final placement. Expressions of interest in studying at universities other than Oxford, Founded by a 1953 Act of Parliament, Marshall Cambridge and London are particularly welcomed. Scholarships are mainly funded by the Foreign, Candidates are especially encouraged to consider the Commonwealth and Development Office and Marshall Partnership Universities. A course search commemorate the humane ideals of the Marshall Plan facility is available here: conceived by General George C Marshall. They express https://www.marshallscholarship.org/study-in-the- the continuing gratitude of the British people to their uk/course-search American counterparts. NB: The selection of Scholars is based on our The objectives of the Marshall Scholarships are: published criteria: https://www.marshallscholarship.org/apply/criteria- • To enable intellectually distinguished young and-who-is-eligible This includes, under the Americans, their country’s future leaders, to study in academic criteria, a range of factors, including a the UK. candidate’s choice of course, choice of university, and academic and personal aptitude. -

International Resources List

International Resources List As an international student interested in attending Columbia School of Social Work, you should expect to have sufficient funding to finance the entire course of study. This handout contains information on government agencies, private organizations, publications and websites that might provide a way to locate funding. This is not a Recommended or Preferred Lender List. This is a simply list of international resources that has been collected based on current and former student experience (shared with us by Columbia Business School colleagues), as well as SW staff scouring the internet for various resouces that offer funding or opportunities to international students. Students have the right and ability to select the lender of their choice and are not required to use any of the resources on this list. NOTE: The information provided below is NOT an endorsement of any organization or scholarship program. The below is being provided for informational purposes only. All students: International Search Engines: Institute of International Education (IIE): IIE, which seeks to foster educational exchange, has great resources for international students. International Education Financial Aid (IEFA): IEFA is the premier resource for financial aid, college scholarship, and grant information for US and international students wishing to study abroad. At this site, you will find the most comprehensive college scholarship search and grant listings, plus international student loan programs and other information to promote study abroad. International Research and Exchanges Board: IREX administers various fellowships for non-degree studies as well as one- and two-year graduate degree studies in the US for foreign nationals within 11 areas of study. -

Scholarships & Fellowships for International Students

Scholarships & Fellowships for International Students AAMC Financing Your Medical Education https://www.aamc.org/what-we-do/aamc-awards A series of grants and awards honoring individuals in the fields of medical education, research, and community service. Deadlines vary. AIA / AAF Minority/Disadvantaged Scholarship http://www.aia.org/education/AIAB081881 Grants ranging from $500-$2,500 for high school seniors and first-years who intend to pursue a NAAB-accredited professional degree (5-year BA or BA + MA) in architecture. Applicants must be legal residents of the United States. Deadline TBD. Albright Institute Fellowships http://www.aiar.org/available-fellowships/ A grant of up to $325,000 in fellowships and awards to 32 recipients who will live at the Albright Institute and study a specific field in archaeology. In addition, 32 Associate Fellows including Senior, Post-Doctoral, and Research Fellows receive funding from other sources. Deadlines vary. Alexander Graham Bell Association for the Deaf and Hard of Hearing http://listeningandspokenlanguage.org/Tertiary.aspx?id=2102 Students who were diagnosed with hearing loss before the age of seven are eligible for a merit-based scholarship ranging from $1,000-$10,000. Deadline March. Allen Lee Hughes Fellowship https://www.arenastage.org/education/fellows-and-interns/ Individuals interested in artistic and technical production, arts administration and community engagement. Fellowship provides a modest stipend and is intended to increase participation of people of color in the arts. Deadline March (summer); April (season). Amelia Earhart Fellowships (Zonta International Foundation) http://www.zonta.org/WhatWeDo/InternationalPrograms/AmeliaEarhartFellowship.aspx Women of any nationality with a superior academic record and a bachelor's degree in science or engineering. -

Trusts and Organisations Offering Scholarships to International Students

Trusts and organisations offering scholarships to international students Below you will find a list of trusts and organizations that award various scholarships to international students. If you are ineligible for a Canon Collins Trust scholarship please look at the options below. Please do not contact Canon Collins Trust regarding queries about these scholarships. The following websites are useful for searching for relevant scholarships: - http://scholarship-positions.com/scholarship-for-south-african-students/2012/05/08/ - http://www.scholarship-search.org.uk/ - http://www.advance-africa.com/Scholarships-and-Grants.html - http://www.educationuk.org/UK/Applications/Scholarships-for-UK-study/scholarships-for-international- postgraduate-students - http://www.soas.ac.uk/registry/scholarships/ - http://www.africadesk.ac.uk/pages/funding/scholarship - http://scholarship-positions.com/scholarships-for-african-students-in-uk/ - http://www.scholars4dev.com/category/target-group/africans-scholarships/ - http://www.european-funding-guide.eu/ For general information about studying in the UK visit: - http://www.ukcisa.org.uk/student/fees_student_support.php - http://www.postgraduatestudentships.co.uk/subject/all-subjects/pgt African Palliative Care Nurses Scholarship Fund Provides a limited number of scholarships each year for Palliative Care Training opportunities for nurses. Web: http://www.africanpalliativecare.org/index.php?option=c Scholarships are awarded up to a maximum of US$ 4,000 om_content&view=article&id=159 through a competitive application process once a year. APCA and FHSSA give priority to requests of Registered and Enrolled nurses to pursue formal palliative care training in Africa. They are also willing to potentially consider one scholarship for a distance Learning Masters programme, when necessary for the career objective of the student (i.e. -

Information Sheet Adapted From

Marshall Scholarship Information Sheet Adapted from http://www.marshallscholarship.org NOTE FOR INTERNATIONAL STUDENTS: Notre Dame students and alumni who are not citizens of the U.S. might consider the Chevening Scholarship. Please visit http://www.chevening.org for more information and contact CUSE National Fellowships at [email protected] so that we can discuss the application process. What is the Marshall Scholarship? The purpose of the Marshall Scholarship, funded by the Foreign and Commonwealth Office of the British government, is to finance young Americans of high ability to study for a degree in the United Kingdom. The award covers tuition, fees, and a generous stipend. Typically, the award lasts for two years, but a limited number of one-year scholarships are awarded. Also, a third-year extension is available for the two-year Marshall in certain cases. Note that the Marshall does not fund undergraduate degrees, the MBA, the MSc/MFE in Financial Economics, the MSc in Global Health Science, the MPP at the University of Oxford, professional degrees, or degrees that require extended periods away from the university or the UK. Who is eligible? Marshall Scholarship applicants must be U.S. citizens and: 1. Hold a first degree from a four-year college or university in the US by the time the Scholarship would begin. The degree must have been awarded no later than the April of two years prior to the application year. (So if one is applying in 2016, the first degree must be awarded between April 2014 and August 2017.) 2. Have a minimum GPA of 3.7, with exceptions in very rare cases. -

VIRTUAL ASPIRE 2021 Building Success Through the Liberal Arts Building Success Through the Liberal Arts

COLLEGE OF ARTS, HUMANITIES, AND SOCIAL SCIENCES UNIVERSITY PRESENTS VIRTUAL ASPIRE 2021 Building Success Through the Liberal Arts Building Success through the Liberal Arts Vision Statement The goal of the Aspire program is to empower students to appreciate, articulate, and leverage the intellectual skills, knowledge, and dispositions unique to a liberal arts education in the service of their personal and professional development. Participants will learn to convey the core values and strengths of their degree program, identify career paths that may connect to that program, and prepare themselves to fur- ther pursue passions and opportunities upon completing their degrees. Thank you to Boston College, Endeavor: The Liberal Arts Advantage for Sophomores, for inspiration and activity ideas. 2 Contents Schedule Overview 4-5 CoAHSS 6-9 Dean’s Advisory Board 10-21 Connect with Us! Guest Speakers 22-24 Campus Resources 25-26 @WPCOAHSS Thank You 27 “What we think, we become.” -Buddha 3 Schedule Overview In-Person Evening Program: Monday, August 2nd Student Center. Rm. 211 5:30pm-6:30pm: Welcome: Program Overview/Introduction: Speakers: o Dr. Wartyna Davis, Dean, College of Arts, Humanities, and Social Science o Dr. Joshua Powers, Provost and Senior Vice President, William Paterson University o Valerie Gross, Dean’s Advisory Board Chair o Selected Student from Aspire 2020, Zhakier Seville Reception: Light Refreshments VIRTUAL Day One Tuesday, August 3th from 9:00am to 2:35pm 9:00– 9:05am Welcome: Dr. Ian Marshall and Lauren Agnew 9:05am-10:00am Virtual Workshops: Career Foundations Group A: The Liberal Arts Advantage: Understanding Yourself through the Strong Interest Inventory Assessment with Ms. -

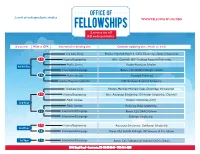

Fellowships Flowchart FA17

A unit of undergraduate studies WWW.FELLOWSHIPS.KU.EDU A service for all KU undergraduates If you are: With a GPA: Interested in funding for: Consider applying for: (details on back) Graduate Study Rhodes, Marshall, Mitchell, Gates-Cambridge, Soros, Schwarzman 3.7+ Science/Engineering Also: Churchill, NSF Graduate Research Fellowship Public Service Knight-Hennessy Scholars 4th/5th Year International/Language Boren, CLS, DAAD, Fulbright, Gilman 3.2+ Public Service Carnegie, Pickering Science/Engineering/SocSci NSF Graduate Research Fellowship Graduate Study Rhodes, Marshall, Mitchell, Gates-Cambridge, Schwarzman 3.7+ Science/Engineering Also: Astronaut Scholarship, Goldwater Scholarship, Churchill Public Service Truman Scholarship (3.5+) 3rd Year Public Service Pickering, Udall Scholarship 3.2+ International/Language Boren, CLS, DAAD, Gilman International/Language Fulbright Scholarship 3.7+ Science/Engineering Astronaut Scholarship, Goldwater Scholarship 2nd Year 3.2+ International/Language Boren, CLS, DAAD, Fulbright UK Summer, (3.5+), Gilman 1st Year 3.2+ International/Language Boren, CLS, Fulbright UK Summer, (3.5+), Gilman 1506 Engel Road • Lawrence, KS 66045-3845 • 785-864-4225 KU National Fellowship Advisors ✪ Michele Arellano Office of Study Abroad WE GUIDE STUDENTS through the process of applying for nationally and internationally Boren and Gilman competitve fellowships and scholarships. Starting with information sessions, workshops and early drafts [email protected] of essays, through application submission and interview preparation, we are here to help you succeed. ❖ Rachel Johnson Office of International Programs Fulbright Programs WWW.FELLOWSHIPS.KU.EDU [email protected] Knight-Hennessy Scholars: Full funding for graduate study at Stanford University. ★ Anne Wallen Office of Fellowships Applicants should demonstrate leadership, civic commitment, and want to join a Campus coordinator for ★ awards. -

Scholarships That Accept Applications from International Students

Scholarships that Accept Applications from International Students AAMC Financing Your Medical Education www.aamc.org/students/financing/start.htm A series of programs to assist students in managing loans and preparing for future financial stability within the Medical field. Deadlines variable. AIA / AAF Minority/Disadvantaged Scholarship http://www.aia.org/education/AIAB081881 Grants ranging from $500-$2,500 for high school seniors and first-years who intend to pursue a NAAB-accredited professional degree (5-year BA or BA + MA) in architecture. Applicants must be legal residents of the United States. Deadline: mid-April. Albright Institute Fellowships http://www.aiar.org/fellowships.html A grant of up to $325,000 in fellowships and awards to 32 recipients who will live at the Albright Institute and study a specific field in archaeology. In addition, 32 Associate Fellows including Senior, Post-Doctoral, and Research Fellows receive funding from other sources. Deadlines variable. Alexander Graham Bell Association for the Deaf and Hard of Hearing http://nc.agbell.org/NetCommunity/Page.aspx?pid=493 Students who were diagnosed with hearing loss before the age of seven are eligible for a merit-based scholarship ranging from $1,000-$10,000. Deadline: mid-March. Allen Lee Hughes Fellowship http://www.arenastage.org/education/education-programs/internships-fellowships/ Individuals interested in artistic and technical production, arts administration and community engagement. Fellowship provides a modest stipend and is intended to increase participation of people of color in the arts. Deadline: mid-March (summer), mid-April (season). All-USA College Academic Team http://www.usatoday.com/news/education/2002-11-04-allstars_x.htm?Loc=vanity Recognition program for exceptional full-time undergraduates at four-year institutions in the USA and its territories. -

Trusts and Organisations Offering Scholarships to International Students

Trusts and organisations offering scholarships to international students Below you will find a list of trusts and organizations that award various scholarships to international students. If you are ineligible for a Canon Collins Trust scholarship please look at the options below. Please do not contact Canon Collins Trust regarding queries about these scholarships. The following websites are useful for searching for relevant scholarships: - http://www.internationalscholarships.dhet.gov.za/scholarships.html - http://scholarship-positions.com/scholarship-for-south-african-students/2012/05/08/ - http://www.scholarship-search.org.uk/ - http://www.advance-africa.com/Scholarships-and-Grants.html - http://www.educationuk.org/UK/Applications/Scholarships-for-UK-study/scholarships-for-international- postgraduate-students - http://www.soas.ac.uk/registry/scholarships/ - http://www.africadesk.ac.uk/pages/funding/scholarship - http://scholarship-positions.com/scholarships-for-african-students-in-uk/ - http://www.scholars4dev.com/category/target-group/africans-scholarships/ - http://www.european-funding-guide.eu/ For general information about studying in the UK visit: - http://www.postgraduatestudentships.co.uk/subject/all-subjects/pgt - http://www.ukcisa.org.uk/student/fees_student_support.php African Palliative Care Nurses Scholarship Fund Provides a limited number of scholarships each year for Palliative Care Training opportunities for nurses. Web: http://www.africanpalliativecare.org/index.php?option=c Scholarships are awarded up to a maximum of US$ 4,000 om_content&view=article&id=159 through a competitive application process once a year. APCA and FHSSA give priority to requests of Registered and Enrolled nurses to pursue formal palliative care training in Africa. They are also willing to potentially consider one scholarship for a distance Learning Masters programme, when necessary for the career objective of the student (i.e. -

Outside International Scholarship List & Application

OPPORTUNITIES FOR INTERNATIONAL STUDENTS Scholarship Scholarship Name & Contact Website Organization Description AAUW Educational Fellowships will be awarded to graduate AAUW Educational Foundation International female foreign students of outstanding Foundation http://www.aauw.org/education/fga/fellowships_gra Fellowships ability who can be expected to give Dept. 60 nts/international.cfm effective leadership in their fields upon 301 ACT Drive return to their home country. Iowa City, IA 52243- 4030 ADAMHA National PhD in areas of biomedical & behavioral Westwood Bldg #240, Research Service research within one of the three NIH http://www.granst1.nih.gov/grants Awards institutes. Bethesda, MD 20892 ph: 301-594-7248 AEI Scholarship Fund Scholarships to female medical students Society Bank 10 South Main St. Ann Arbor, MI 48104 ph: 313-994-5555 African-American 833 United Nations Institute Plaza New York, N.Y. 10017 Agency for Health Care Grants for Dissertation Research. For Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality students in the social, medical, Research and Quality http://www.ahrq.gov/ management or health sciences. Grants Management 540 Gaither Road, Suite 4000 Rockville, MD 20850 Alexander Graham Bell Administering various awards for 3417 Volta Place, NW Association for the Deaf auditory-oral students who a) were born Washington, D.C. http://www.agbell.org/ with profound hearing losses, or b) 20007 experienced a severe hearing loss before acquiring language. Applicants must enroll in a college or university program that primarily enrolls students with normal hearing. American Antiquarian Dissertation fellowships for conducting 185 Salisbury St. Society research using AAS library's resources. Worcester, MA 01609 http://www.americanantiquarian.org/ ph: 508-752-5221 American Association for 10 weeks summer fellowships at the 1333 H St. -

Dartmouth College • Fellowship Advising

DARTMOUTH COLLEGE • FELLOWSHIP ADVISING NATIONAL SCHOLARSHIPS AND FELLOWSHIPS BY YEAR OF APPLICATION Sophomores Critical Language Scholarship Fulbright Summer Institute (programs at UK universities) Gilman Scholarship (study abroad programs) Goldwater Scholarship (research careers in STEM fields) Boren/NSEP Scholarship for Study Abroad Udall Scholarship (careers in the environment, Native health care, or tribal public policy) Juniors Critical Language Scholarship Gilman Scholarship (study abroad programs) Goldwater Scholarship (research careers in STEM fields) Udall Scholarship (careers in the environment, Native health care, or tribal public policy) Truman Scholarship (careers in public service) Beinecke Scholarship (graduate study in the arts, social sciences or humanities) Boren/NSEP Scholarship for Study Abroad Pickering Fellowship (careers in the Foreign Service) Seniors and Alumni Study Abroad: Rhodes Scholarship (study at Oxford) Marshall Scholarship (study in the UK) Mitchell Scholarship (study in Ireland) Fulbright Research and Teaching Assistantship (study or teaching in approx. 140 countries) Churchill Scholarship (study at Cambridge, STEM fields) DAAD Scholarship (study in Germany) Gates Cambridge Scholarship (study at Cambridge) Gilman Scholarship (study abroad programs) Keasbey Scholarship (study at Oxford, Cambridge, Edinburgh, or Wales) Luce Scholarship (internships in East Asia, any field except Asian specialties) Schwarzman Scholars Program (at Tsinghua University in Beijing) St. Andrew’s Society Graduate Scholarship -

HMG Scholarships Cluster Review March 2015

HMG Scholarships Cluster Review March 2015 The review was conducted by: Amanda Spielman, Chair of Ofqual. 1 Contents Executive Summary 3 Recommendations 6 Context, Purpose and Scope 9 Rationale 12 Implementation 16 Scheme Descriptions 21 Scheme Allocation 27 Scheme Oversight 31 Scheme Phases 33 Scheme Finances 38 Annexes 45 A – Terms of Reference 46 B – 2013 Triennial Review of CSC - Recommendations 48 C – 2013 Triennial Review of MACC - 50 Recommendations D – 2014 Internal Review of the Chevening 52 Programme - Recommendations E – Commonwealth Scholarship Scheme Overview 54 F – Marshall Scholarship Scheme Overview 55 G – Chevening Scholarship Programme Overview 56 H – Newton Fund Overview 57 I – Chevening Administration Cost Efficiencies – 59 note prepared by ACU J – Scholarship Country Coverage 62 K – Stakeholders Consulted 67 2 Scholarships Cluster Review Executive Summary Context This cluster review follows the individual triennial reviews of the two scholarship non- departmental public bodies(NDPB), the Commonwealth Scholarship Commission (CSC) and the Marshall Aid Commemoration Commission (MACC), as well as an internal review by the FCO of the Chevening scholarship scheme. Its aim was to find whether there is scope for further efficiencies and synergies, and if so what structure, administration or delivery might realise those improvements. Scholarship schemes build soft power, in the short and long term; they promote international development; they enhance the reputation of UK universities; they recognise and promote the highest standards of intellectual achievement; they build international academic communities; they recognise and promote the highest standards of intellectual achievement; and they project British excellence abroad, promoting the UK internationally as a place to visit, study and do business.