“Nursing Standards, Guidelines, Protocols in Bih – Best Case Reporting

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Law Amending the Law on the Courts of The

LAW AMENDING THE LAW ON COURTS OF THE REPUBLIKA SRPSKA Article 1 In the Law on Courts of the Republika Srpska (“Official Gazette of the Republika Srpska”, No: 37/12) in Article 26, paragraph 1, lines b), e), l) and nj) shall be amended to read as follows: “b) the Basic Court in Bijeljina, for the territory of the Bijeljina city, and Ugljevik and Lopare municipalities,”, “e) the Basic Court in Doboj, for the territory of Doboj city and Petrovo and Stanari municipalities,”, “l) the Basic Court in Prijedor, for the territory of Prijedor city, and Oštra Luka and Kozarska Dubica municipalities,” and “nj) the Basic Court in Trebinje, for the territory of Trebinje city, and Ljubinje, Berkovići, Bileća, Istočni Mostar, Nevesinje and Gacko municipalities,”. Article 2 In Article 28, in line g), after the wording: “of this Law” and comma punctuation mark, the word: “and” shall be deleted. In line d), after the wording: “of this Law”, the word: “and” shall be added as well as the new line đ) to read as follows: “đ) the District Court in Prijedor, for the territories covered by the Basic Courts in Prijedor and Novi Grad, and for the territory covered by the Basic Court in Kozarska Dubica in accordance with conditions from Article 99 of this Law.” Article 3 In Article 29, line g), after the wording: “the District Commercial Court in Trebinje”, the word: “and” shall be deleted and a comma punctuation mark shall be inserted. In line d), after the wording: “the District Commercial Court in East Sarajevo”, the word: “and” shall be added as well as the -

The-Prijedor-Genocide 1

PART 1. THE PRIJEDOR GENOCIDE The Prijedor genocide [1][2][3] , refers to numerous war crimes committed during the Bosnian war by the Serb political and military leadership mostly on Bosniak civilians in the Prijedor region of Bosnia-Herzegovina. After the Srebrenica genocide, it is the second largest massacre committed during the Bosnian war in 1992. Around 5,200 Bosniaks and Croats from Prijedor are missing or were killed during the massacre period, and around 14,000 people in the wider region of Prijedor (Pounje). [4] Contents • 1 Background • 2 Political developments before the takeover • 3 Takeover • 4 Armed attacks against the civilians o 4.1 Propaganda o 4.2 Strengthening of Serb forces o 4.3 Marking of non-Serb houses o 4.4 Attack on Hambarine o 4.5 Attack on Kozarac • 5 Camps o 5.1 Keraterm camp o 5.2 Omarska camp o 5.3 Trnopolje camp o 5.4 Other detention facilities • 6 Killings in the camps • 7 References • 8 See also • 9 External links Background Following Slovenia’s and Croatia’s declarations of independence in June 1991, the situation in the Prijedor municipality rapidly deteriorated. During the war in Croatia, the tension increased between the Serbs and the communities of Bosniaks and Croats. Bosniaks and Croats began to leave the municipality because of a growing sense of insecurity and fear amongst the population which was caused by Serb propaganda which became increasingly visible. The municipal newspaper Kozarski Vjesnik started publishing allegations against the non-Serbs. The Serb media propagandised the idea that the Serbs had to arm themselves. -

The Continuing Challenge of Refugee Return in Bosnia & Herzegovina

THE CONTINUING CHALLENGE OF REFUGEE RETURN IN BOSNIA & HERZEGOVINA 13 December 2002 Balkans Report N°137 Sarajevo/Brussels TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS ...................................................i I. INTRODUCTION ...............................................................................................................1 II. RETURN AND DISPLACEMENT IN 2002...................................................................4 III. NATIONALIST STEREOTYPES AND THE POLITICAL IMPACT OF RETURN...............................................................................................................................5 IV. CREATING SPACE FOR RETURN OR RELOCATION?........................................7 A. RECONSTRUCTION ASSISTANCE........................................................................................ 7 B. PROPERTY REPOSSESSION ................................................................................................ 9 C. RETURNING TO SELL? .....................................................................................................11 D. ILLEGAL LAND ALLOCATION TO REFUGEES: DEMOGRAPHIC ENGINEERING CONTINUES .....11 V. REASONS NOT TO RETURN.......................................................................................14 A. DISCRIMINATION IN A DEPRESSED ECONOMY...................................................................14 B. MONO-ETHNIC INSTITUTIONS..........................................................................................16 C. SECURITY.......................................................................................................................18 -

Trans-European North-South Motorway (Tem)

TRANS-EUROPEAN NORTH-SOUTH MOTORWAY (TEM) 4-7 June 2017, Dubrovnik, Croatia PUBLIC COMPANY “REPUBLIC OF SRPSKA MOTORWAYS” Ltd. • MANAGEMENT , CONSTRUCTION, MAINTENANCE AND PROTECTION OF EXPRESSWAYS AND MOTORWAYS IN THE REPUBLIC OF SRPSKA ARE CARRIED OUT BY PUBLIC COMPANY “REPUBLIC OF SRPSKA MOTORWAYS” ltd The motorway network in RS includes following directions (alignments): 1. Banja Luka – Gradiška L= 35 km 2. Mahovljani interchange 3. Banja Luka – Prnjavor, L=35,30 km 4. Prnjavor – Doboj, L =36,6 km 5. Glamočani – Mliništa, L = 92 km 5. Doboj – Vukosavlje, L = 46,6 km 6. Banja Luka – Prijedor– Novi Grad, L = 71 km 7. Vukosavlje – Bijeljina, L = 62 km APART FROM CONSTRUCTION OF MOTORWAY SECTIONS, STRATEGIC PLANS INCLUDE CONSTRUCTION OF FOLLOWING EXPRESSWAYS IN TOTAL LENGHT OF 468 KM: • Lukavica– Pale – Sokolac – Rogatica- Višegrad (128) км • Bijeljina – Zvornik– Sokolac (145 km) • Sokolac – Rogatica – Foča – Gacko – Bileća – Trebinje (160 km) • Prijedor– Kozarska Dubica– Donja Gradina (50 km) • Banja Luka – Čelinac– Kotor Varoš– Obodnik (50 km ) • Stolac– Ljubinje– Trebinje– granica sa Crnom Gorom (95 км) Previous, Current and future Activities EBRD/EIB EBRD/EC EBRD EIB Vc through RS, L=46,6 km Preparatory activities Asset management, routine maintenance, structural maintenance, operations? • Asset management is the strategic business process approach to managing the long-term maintenance of roads • Routine maintenance - All works and services which are believed to be necessary to achieve the best possible results with regard to the availability, reliability and sustainability of the Highway. These services are essential to ensure the safety of the road users and for the proper management and communication of all incidents as well as of all planned maintenance works and to ascertain that the condition and status of the Highway is maintained. -

Congress Observed the Elections in Republika Srpska

Press Release Communication Unit of the Congress of Local and Regional Authorities Ref:906a07 Tel: : +33 3 90 21 49 36 Fax : +33 3 88 41 27 51 [email protected] www.coe.int/congress Congress-Council of Europe Observation Mission for the 47 members Elections of the President of the Republic of Srpska (Bosnia and Herzegovina) Albania Andorra Sarajevo, 10.12.2007 - A delegation of the Congress of Local and Regional Authorities of Armenia Austria the Council of Europe, on the official invitation by the BiH authorities, observed voting in Azerbaijan the elections for the President of the Republic of Srpska (Bosnia and Herzegovina) on Belgium Sunday 9 December. Bosnia and Herzegovina The delegation was deployed in many localities within the Republic of Srpska, and Bulgaria participated in preparatory meetings in Banja Luka, Prijedor, Sarajevo, Mostar and Croatia Nevesinje. On Election Day, Giorgi Masalkini - Congress Rapporteur - led a team which Cyprus observed elections in polling stations in Banja Luka and the surrounding area. A second Czech Republic team observed polling in the region east of Sarajevo (Pale, Sokolac, Rogatica). Denmark Estonia Finland The turn-out for these elections was notably low, despite the campaigning of some France candidates. Owen Masters, Head of the Mission, said that “the elections observed were Georgia generally in accordance with Council of Europe and international standards”. He added Germany that “it was encouraging to see the younger generation taking on electoral Greece responsibilities”. Early on Election Day, some voters had difficulties locating their specific Hungary voting station, but it should be noted that measures were soon put in place to address this Iceland problem. -

United Nations / Ujedinjene Nacije / Уједињене Нације Bosnia And

United Nations / Ujedinjene nacije / Уједињене нације Office of the Resident Coordinator / Ured rezidentnog koordinatora / Уред резидентног координатора Bosnia and Herzegovina / Bosna i Hercegovina / Босна и Херцеговина Bosnia and Herzegovina – Flood Disaster Situation Report June 1, 2014 HIGHLIGHTS/KEY PRIORITIES: ! Reported increase in the number of landlides; Local authorities have been taking necessary measures to evacuate the population in danger and to keep landslides under control. ! Weather conditions will be worsening in the following few days with a chance of rain and thunderstorms across the country; ! Federal and Republic of Srpska Hydrological Report indicates that water levels are in most locations going down while in some are stagnating; ! There is an emerging need to collate WASH rapid needs assessments and to triangulate information with government information. UNICEF lead WASH Coordination meeting held on May 28, 2014 hosted 28 participants from the civil sector, UN Agencies and Embassies (ADRA, EU, IFRCO, FDA, OSCE, OXFAM, SIDA, SOS Children Village, STC, Swiss Embassy, UNICEF, US Embassy, WHO, World Vision) sharing information on the assessments being undertaken. ! In many locations water systems have been re-established, water is still not potable in most areas; ! Epidemiological situation is stable and no outbreaks have been reported in flood-stricken areas. ! DoboJ, MaglaJ, Olovo, Una-Sana Canton and Posavina region at the basin of Bosna, Krivaja and Usora rivers have been identified as mine and UXOs suspected areas; ! Number of persons accommodated in temporary accommodation facilities is 1384: number of temporary accommodation facilities reported to be 42. ! Emerging priorities are soil decontamination, replanting of seeds in time for the crops season, livestock repopulation, feed for livestock, housing, reestablishment of services from the municipalities and reconstruction of the industrial and commercial network ! Joint UN-EU-World Bank rapid assessment training took place on May 29-30. -

5 4 Prioritizing Investments in the Intermediate Scenario

Annex 1. Primary and secondary roads - a foundation for private sector led growth Public Disclosure Authorized Transport Sector Review: Bosnia and Herzegovina - the road to Europe Transport Unit, Sustainable Development Department Europe and Central Asia Region May 2010 Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Document of the World Bank Table of Contents 1 REVIEW OF THE INSTITUTIONAL FRAMEWORK ................................................................ 3 The legal and regulatory framework..................................................................................................... 3 Compliance with the acquis communautaire ........................................................................................ 4 The policy framework ........................................................................................................................... 6 Organizational structure of the road sector .......................................................................................... 7 The classification of roads ...................................................................................................................12 2 ASSETS IN THE ROAD SECTOR ..................................................................................................14 The European dimension .....................................................................................................................14 Road infrastructure ..............................................................................................................................14 -

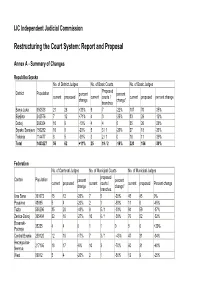

Restructuring the Court System: Report and Proposal

IJC Independent Judicial Commission Restructuring the Court System: Report and Proposal Annex A - Summary of Changes Republika Srpska No. of District Judges No. of Basic Courts No. of Basic Judges Proposed District Population percent percent current proposed current courts / current proposed percent change change change* branches Banja Luka 650538 21 28 +33% 9 7 -22% 107 70 -35% Bijeljina 242576 7 12 +71% 4 3 -25% 33 29 -12% Doboj 269354 10 9 -10% 4 4 0 35 26 -26% Srpsko Sarajevo 156282 10 8 -20% 5 3 / 1 -20% 27 18 -33% Trebinje 114477 8 5 -38% 3 2 / 1 0 18 11 -39% Total 1433227 56 62 +11% 25 19 / 2 -16% 220 154 -30% Federation No. of Cantonal Judges No. of Municipal Courts No. of Municipal Judges proposed Canton Population percent percent current proposed current courts / current proposed Percent change change change* branches Una Sana 301072 15 12 -20% 7 5 -29% 45 45 0% Posavina 43695 5 4 -20% 2 1 -50% 11 6 -45% Tuzla 506296 35 20 -43% 9 5 / 1 -33% 94 59 -37% Zenica-Doboj 395404 22 16 -27% 10 6 / 1 -30% 76 52 -32% Bosanski- 35235 4 4 0 1 1 0 5 6 +20% Podrinje Central Bosnia 239120 12 10 -17% 7 3 / 1 -43% 47 31 -34% Herzegovina- 217106 18 17 -6% 10 3 -70% 60 31 -48% Neretva West 89012 5 4 -20% 2 1 -50% 12 9 -25% Herzegovina Sarajevo 400219 37 29 -22% 2 1 -50% 75 92 +23% Canton 10 83949 5 4 -20% 3 1 / 1 -33% 9 7 -22% (Livno) Total 2311108 158 120 -24% 53 27 / 4 -42% 434 338 -22% Total for BiH No. -

Marginalized Populations Support Activty (Ppmg)

2018 PORTFOLIO REVIEW (#4) ACTIVITY REPORT REPORTING PERIOD: December 2017- December 2018 ACTIVITY NAME: MARGINALIZED POPULATIONS SUPPORT ACTIVTY (PPMG) ACTIVITY OVERVIEW Activity Purpose: Individuals and CSOs representing underrepresented groups are constructively engaged in civic/political issues, will ensure that the government recognizes them as necessary and respectable partners in policy development. The Development Hypothesis: Constructive engagement in civic/political issues of individuals and CSOs representing underrepresented groups will be achieved by supporting the activities of groups of local organizations that advocate for the rights and dignity of underrepresented groups, building capacities of local NGOs and USAID implementing partners and providing grants to local CSOs that provide services to beneficiaries. Implementing Partner: . Institute for Youth Development KULT Activity Website: . Yes; url: www.ppmg.ba Activity Facebook page: . Yes, url: https://www.facebook.com/ppmg.ba/ COR/AOR: Ela Challenger COP Name: Jasmin Bešić Key Partners/Other Donors: NGO & BA d.o.o. Start /End Date: February, 2015 / February, 2022 Total Estimated Cost: $ 4,999,000.00 USD Obligated Amount: $ 4,219,245.67 Mortgage: $779,754.33 RESULTS ACHIEVED The Activity’s highest-level result statement: Increased citizen’s participation in governance. Contribution to Project log frame indicators (list the log frame indicators that this activity is contributing to, the targets, and the FY18 Results): Indicator Activity Targets for Activity Results -

Рударски Институт Приједор Institute of Mining Prijedor

РУДАРСКИ ИНСТИТУТ ПРИЈЕДОР INSTITUTE OF MINING PRIJEDOR What? hat? What? - is an European project financed under the framework of the European Institute of Innovation and Technology. WThe project includes 9 partners in total with the University of Zagreb‑Faculty of Mining, Geology and Petroleum engineering (UNIZG -RGNF) as the project coordinator. The duration of the project is three years and the budget is a bit over 300.000 euros. Who? ho? Who? The project consortium is consisted of 9 organizations from the ESEE region: University of Zagreb‑Faculty of Mining, Geology andW Petroleum engineering (Croatia), Montanuniver- sität Leoben (Austria), Geological Survey of Slovenia – GeoZS (Slovenia), CEMEX (Croatia), Institute for urbanism, civil engineer- ing and ecology (Bosnia&Herzegovina), Mining Institute Banja Luka (B&H), Mining institute Prijedor (B&H), Mining Institute Tuz- la (B&H), University of Zenica (B&H), Metalurgical institute Kemal Kapetanović (B&H). Why?hy? Why? After a decade of declining commodity prices, negative in- vestment trends, debated mining legislation and increased over- all risks, mining companiesW are struggling to survive searching for new sustainable investment options. Interaction between local and European industry and investors will provide a user- -friendly online platform and knowledge transfer to encour- age any possible learning curve of local SMEs and eco‑system. In- vestRM will provide a compatible intelligence network structure delivering a web portal including specific country maps, busi- ness requirements and opportunities the in raw material sector, and furthermore facilitates investors to enter into this market. The project is focused on Bosnia and Hercegovina due to its criti- cal raw materials potential but will be fully transferable to other Who? East and Southeast European (ESEE) countries. -

World Bank Document

Report No. PID8399 Project Name Bosnia and Herzegovina-Third Electric (@+) Power Reconstruction Project Region Europe and Central Asia Region Sector Distribution & Transmission Public Disclosure Authorized Project ID BAPE58521 Borrower(s) Bosnia and Herzegovina Implementing Agency Address EPBIH, EPM AND EPRS Address: See below. Environment Category B Date PID Prepared March 20, 2000 Projected Appraisal Date March 28, 2000 Public Disclosure Authorized Projected Board Date May 30, 2000 1. Country and Sector Background (i) Reconstructing the power system. In 1990, BiH produced 12,900 Gigawatt hours (GWh) of electricity from generating plants located on its territory. Electricity consumption was 11,822 GWh. The system comprised 13 hydropower plants with a total capacity of 2,034 megawatts (MW) and an average output of 6,922 GWh/year, and 12 thermal power plants with a total capacity of 1,957 MW and an output of 9,252 GWh in 1990. The thermal power plants were brown coal and lignite fired, with the fuel coming from mines within BiH. BiH was responsible for operating its own system and meeting local demand. However, being part of the former Yugoslav network, the 400 kilovolt (kV) power grid in BiH was controlled by the Yugoslav Electric Power Industry's (JUGEL) dispatching center in Belgrade. Power Public Disclosure Authorized exchanges were also controlled by JUGEL.At the beginning of 1996, more than half of generating capacity had been put out of operation because of direct damages, destroyed transmission lines or lack of coal. Most plants had also suffered from lack of maintenance during the war. About 60% of the transmission network and control system in the Federation was seriously damaged, including transmission facilities and interconnection lines to neighboring countries. -

Prijedor: Re-Imagining the Future Damir Mitrić and Sudbin Musić

46 Bosnia and Herzegovina twenty years on from the Dayton Peace Agreement FMR 50 www.fmreview.org/dayton20 September 2015 Prijedor: re-imagining the future Damir Mitrić and Sudbin Musić Public memorialisation in Bosnia and Herzegovina today is an act of remembering not just those who died in the conflict but also the multi-ethnic reality of earlier times. Articulation of this, however, is being obstructed in cities like Prijedor. The political elites of post-Dayton Bosnia Srpska (RS), with the immediate post-war and Herzegovina (BiH) have carefully political leadership dominated by those patrolled their respective histories of ‘what who had ‘ethnically cleansed’ the town of happened’ during the war, with school its non-Serb population.1 Annex 7 of the curricula, public broadcasting, public Dayton Peace Agreement established the events and memorial sites on all sides right of all refugees and displaced persons mostly narrating an un-nuanced story to return freely to their homes of origin, and of victim and perpetrator. Imposing an was generally successfully implemented in embargo on memories of pre-war BiH has Prijedor, in contrast to other parts of BiH; become an important component of this. between 1998 and 2003 some 10,000 Bosniaks In the north-western town of Prijedor, decided to return to the place of their birth. a systematically executed policy of However, only 20% of the original Bosniak ethnic cleansing resulted in the killing of population has permanently returned. Until 3,173 residents at the hands of local Serb 2007, reclaiming and rebuilding destroyed authorities, with a third executed in the private property had been the primary driver three infamous concentration camps of of return.