Appendix the Dao of Ink and Dharma Objects—On Jizi's Paintings

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On the Research Status of the Storm Society

International Journal of Science Vol.2 No.12 2015 ISSN: 1813-4890 On the Research Status of the Storm Society Hao Xing School of history, Hebei University, Baoding 071002, China [email protected] Abstract The Storm Society is the first well-organized art association, which consciously absorb the western modern art achievements in Chinese modern art history. Based on the historical materials, this paper describes the basic facts of the Storm Society, and analyze the research status and weakness of this organization, and summarizes its historical and practical significance in the transformation of Chinese art from traditional form to modern form. Keywords the Storm Society, Art Magazine, research status. 1. The Basic Facts of the Storm Society The Storm Society is brewed in 1930. Its predecessor is "moss Mongolia", which is a painting group organized by Xunqin Pang, but it is soon seized. Xunqin Pang says,”I feel deeply distressed that the spirit of Chinese art and literature is decaying and corrupting, but my shallow knowledge and ability is not enough to pull the decadent a little. So I decide to gather some comrades to strive for the hope of making some contribution to the world together. This is the origin of the Storm Society.” The Storm Society is established in Nanjing in 1931, aiming at probing and developing China’s oil painting art. The main sponsors of the group are Xunqin Pang,Yide Ni , Jiyuan Wang , Zhentai Zhou , Ping Duan , Xian Zhang , Taiyang Yang , Qiuren Yang , Di Qiu , et al. The so-called "storm" means that this organization attempts to break the old barrier of traditional art, and sets off a raging tide of new art. -

Research and Education in the Contemporary Context of Art History from the Vision to the Art

3rd International Conference on Education, Management and Computing Technology (ICEMCT 2016) Research and Education in the Contemporary Context of Art History From the Vision to the Art Weikun Hao Hebei Institute of Fine Art, Shijiazhuang Hebei, 050700, China Keywords: Oil painting Techniques; Digital Image; Teaching Abstract. As is known to all, today's art education, its function has been far beyond the scope of training professional art talents. And from the perspective of the status quo of higher art education and skill training compared with history research, history research obviously in a weak position. From the Angle of art, art history is one of the important part of human art and culture, several conclusions show that for the study of art history and also learn the meaning of the obvious, such as improve the level of the fine arts disciplines, from the pure skills subject ascended to the status of the humanities; For today calls a "visual arts" or "visual culture" study, art history research is necessary; In carrying forward traditional culture today, the study of art history and learning will make human have more opportunity to participate in the fine arts with the human, and life, and emotion, contact with politics and history, for more understanding of cultural phenomenon. Introduction Plays a role in history of art history, art history research in the history of the grand is indispensable in the background, the history and culture is the concept of two inseparable. Obviously, for art history research to let a person produce both witness the massiness of history, and to experience the many things like the ramifications of fine arts. -

Download Article

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 341 5th International Conference on Arts, Design and Contemporary Education (ICADCE 2019) Exploring the Influence of Western Modern Composition on Image Oil Painting After "The Fine of 1985" Shisheng Lyu Haiying Liu College of Art and Design College of Art and Design Wuhan Textile University Wuhan Textile University Wuhan, China 430073 Wuhan, China 430073 Abstract—This paper starts with the modern composition in modern composition. They have various painting genres of the West. Through the development of Chinese imagery oil and expressions, enriching the art form of oil painting. painting in China and its influence on Chinese art, this paper explores the influence and development of the post-modern Since the 1980s, with the gradual acceleration of reform composition on China's image oil painting after "The Fine of and opening up, Chinese art has withstood the invasion of 1985". Firstly, it analyzes the historical and cultural foreign cultures and experienced the innovation of cultural background and characteristics of Western modern and artistic thoughts. Image oil paintings have turned their composition. Secondly, it focuses on the development of attention to the exploration of the sense of form of art modern composition in China, and elaborates on the artistic ontology and have made valuable explorations in painting expressions of Chinese image oil painters influenced by form and language of expression, which is largely influenced modern composition. Finally, it considers the main reason why by the form and language of Western modern composition. Chinese image oil painting is influenced by modern Some contemporary oil painters have deeply studied the composition. -

Wu Guanzhong's Artistic Career Yong Zhang1,*

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 572 Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Arts, Design and Contemporary Education (ICADCE 2021) Wu Guanzhong's Artistic Career Yong Zhang1,* 1 State Specialist Institute of Arts, Rezervnyy Proyezd, D.12, Moscow, 121165 Russia *Corresponding author. Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT Combining with Wu Guanzhong's learning experience, this paper analyzes Chinese oil painting art characteristics in different periods, and the method of integrating traditional Chinese ink and wash painting language with the western modern design language in the aspects such as modelling, colour and composition. Wu Guanzhong successfully used western painting method to show the Oriental artistic conception, and formed unique composition views and forms. With the use of concise and simple colors and free-writing lines, the painter's personal emotions, thoughts and standpoint and deep understanding of life can be expressed. On the basis of in-depth research on the essence, connotation and thought of Chinese and Western art, Wu Guanzhong found the "junction" of the integration of Chinese and Western art. Keywords: Wu Guanzhong, Hangzhou Academy of Art, Ink and wash painting, Oil painting, Integration of Chinese and Western art. 1. INTRODUCTION Wu Guanzhong entered Hangzhou Academy of Art to study Chinese and Western paintings. In the Wu Guanzhong (1919-2010), the People's school, he received direct guidance from teachers Artist, Art Educator, and Professor of the Academy such as Li Chaoshi, Fang Ganmin, and Pan of Arts and Design of Tsinghua University, used to Tianshou. Li Chaoshi and Fang Ganmin are both be an executive director of the Chinese Artists teachers who have returned from studying in Association, a member of the Standing Committee France, but their styles of painting are different. -

Powers C.V. November 20 2020

March, 2020 Martin Joseph Powers Professor Emeritus, University of Michigan E-mail: [email protected] Education: Ph.D. 1978 University of Chicago, Department of Art History M.A. 1974 University of Chicago, Department of Art History B.A. 1972 Shimer College, Illinois Professional Employment: University of Michigan, Ann Arbor 1999-2018 Sally Michelson Davidson Professor of Chinese Arts and Cultures, 1988 – 1999 Associate Professor, Department of the History of Art University of California, Los Angeles 1985-1988 Associate Professor, Department of Art History 1978-1985 Assistant Professor, Department of Art History 1977-1978 Visiting Professor, Department of Art History Awards; Appointments: 2020, Jan.—Dec. Honorary Professor, Guangzhou Academy of Fine Arts 10/1/19—6/15/2020 Visiting Professor, University of Chicago 1/1/19-6/15/19 Visiting Professor, University of Chicago 10/1/17-05/16/18 Visiting Professor, University of Chicago 2013 (Spring) The China Academy of Art, the Pan Tianshou Memorial Lectures (4) 2012 (Spring) Tsinghua University, the Wang Guowei Memorial Lectures (8) 2011 Center for Advanced Study in the Visual Arts Mellon Fellow, declined. 2008-2009 Fellow, School of Historical Studies, Princeton Institute for Advanced Study 2008 Joseph Levenson Prize for the best book on pre-1900 China 2006 - 2009 Member, CASVA Board of Advisors 2007 Innaurugal lecture, Shih Hsio-yen Endowed Lecture Series, Hong Kong University 2006 – 2008 (Summer) Visiting Professor, History Department, Tsinghua University 2005 (Summer) Weilun Visiting Professor, History, Tsinghua University 2000 (Summer) Resident Faculty, Summer Institute for World Art Studies, University of East Anglia 1999-2018 Sally Michelson Davidson Professor of Chinese Arts and Cultures 1997 The Sammy Lee Endowed Lecture, U.C.L.A. -

China Daily 0803 D6.Indd

life CHINA DAILY CHINADAILY.COM.CN/LIFE FRIDAY, AUGUST 3, 2012 | PAGE 18 Li Keran bucks market trend The artist has become a favorite at auction and his works are fetching record prices. But overall, the Chinese contemporary art market has cooled, Lin Qi reports in Beijing. i Keran (1907-89) took center and how representative the work is, in addi- stage at the spring sales with tion to the art publications and catalogues it two historic works both cross- has appeared in.” ing the 100 million yuan ($16 Though a record was set by Wan Shan million) threshold. Hong Bian, two other important paintings by His 1974 painting of former Li were unsold, which came as no surprise for Lchairman Mao Zedong’s residence in Sha- art collectors like Yan An. oshan, the revolutionary holy land in Hunan “Both big players and new buyers are bid- province, fetched 124 million yuan at China ding for the best works of the blue-chip art- Guardian, in May. ists, while the market can’t provide as many Th ree weeks later his large-scale blockbust- top-notch artworks and provide the reduced er of 1964, Wan Shan Hong Bian (Th ousands risks that people expect. of Hills in a Crimsoned View), was sold for a “Th is is because in the face of an unclear personal record of 293 million yuan at Poly market, cautious owners would rather keep International Auction. those items, which achieved skyscraping Li, a prominent figure in 20th-century prices, rather than fl ip them at auction,” Yan Chinese art, is recognized for innovating the says. -

Behind the Thriving Scene of the Chinese Art Market -- a Research

Behind the thriving scene of the Chinese art market -- A research into major market trends at Chinese art market, 2006- 2011 Lifan Gong Student Nr. 360193 13 July 2012 [email protected] Supervisor: Dr. F.R.R.Vermeylen Second reader: Dr. Marilena Vecco Master Thesis Cultural economics & Cultural entrepreneurship Erasmus School of History, Culture and Communication Erasmus University Rotterdam 1 Abstract Since 2006, the Chinese art market has amazed the world with an unprecedented growth rate. Due to its recent emergence and disparity from the Western art market, it remains an indispensable yet unfamiliar subject for the art world. This study penetrates through the thriving scene of the Chinese art market, fills part of the gap by presenting an in-depth analysis of its market structure, and depicts the route of development during 2006-2011, the booming period of the Chinese art market. As one of the most important and largest emerging art markets, what are the key trends in the Chinese art market from 2006 to 2011? This question serves as the main research question that guides throughout the research. To answer this question, research at three levels is unfolded, with regards to the functioning of the Chinese art market, the geographical shift from west to east, and the market performance of contemporary Chinese art. As the most vibrant art category, Contemporary Chinese art is chosen as the focal art sector in the empirical part since its transaction cover both the Western and Eastern art market and it really took off at secondary art market since 2005, in line with the booming period of the Chinese art market. -

At the End of the Stream: Copy in 14Th to 17Th Century China

Renaissance 3/2018 - 1 Dan Xu At the End of the Stream: Copy in 14th to 17th Century China There were no single words in Chinese equivalent to By the 14th century the three formats became the form the English word copy. By contrast, there were four preferred by artists, and remained unchallenged until distinctive types of copy: Mo (摹 ), the exact copy, was the early 1900s, when the European tradition of easel produced according to the original piece or the sketch painting came to provide an alternative.[1] The album of the original piece; Lin (临 ) denotes the imitation of was the last major painting format to develop. It ar- an original, with a certain level of resemblance; Fang rived along with the evolution of leaf-books. The album (仿 ) means the artistic copy of a certain style, vaguely was first used to preserve small paintings, later being connected with the original; and the last one, Zao (造 ), adopted by artists as a new format for original work refers to purely inventive works assigned to a certain and also as teaching resource or notebook for the master’s name. artist himself. Pictorial art in China frst emerged as patterns on In the process of the material change, it’s note- ritual vessels, then was transmitted to wall paintings worthy that Mo, the faithful copy, was involved in three and interior screens; later it was realised on horizontal slightly different ways: 1. to transmit an image from hand scrolls, vertical hanging scrolls and albums. manuscript/powder version to final work; 2. -

Writing Memory

Corso di Dottorato di ricerca in Studi sull’Asia e sull’Africa, 30° ciclo ED 120 – Littérature française et comparée EA 172 Centre d'études et de recherches comparatistes WRITING MEMORY: GLOBAL CHINESE LITERATURE IN POLYGLOSSIA Thèse en cotutelle soutenue le 6 juillet 2018 à l’Université Ca’ Foscari Venezia en vue de l’obtention du grade académique de : Dottore di ricerca in Studi sull’Asia e sull’Africa (Ca’ Foscari), SSD: L-OR/21 Docteur en Littérature générale et comparée (Paris 3) Directeurs de recherche Mme Nicoletta Pesaro (Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia) M. Yinde Zhang (Université Sorbonne Nouvelle – Paris 3) Membres du jury M. Philippe Daros (Université Sorbonne Nouvelle – Paris 3) Mme Barbara Leonesi (Università degli Studi di Torino) Mme Nicoletta Pesaro (Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia) M. Yinde Zhang (Université Sorbonne Nouvelle – Paris 3) Doctorante Martina Codeluppi Année académique 2017/18 Corso di Dottorato di ricerca in Studi sull’Asia e sull’Africa, 30° ciclo ED 120 – Littérature française et comparée EA 172 Centre d'études et de recherches comparatistes Tesi in cotutela con l’Université Sorbonne Nouvelle – Paris 3: WRITING MEMORY: GLOBAL CHINESE LITERATURE IN POLYGLOSSIA SSD: L-OR/21 – Littérature générale et comparée Coordinatore del Dottorato Prof. Patrick Heinrich (Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia) Supervisori Prof.ssa Nicoletta Pesaro (Università Ca’ Foscari Venezia) Prof. Yinde Zhang (Université Sorbonne Nouvelle – Paris 3) Dottoranda Martina Codeluppi Matricola 840376 3 Écrire la mémoire : littérature chinoise globale en polyglossie Résumé : Cette thèse vise à examiner la représentation des mémoires fictionnelles dans le cadre global de la littérature chinoise contemporaine, en montrant l’influence du déplacement et du translinguisme sur les œuvres des auteurs qui écrivent soit de la Chine continentale soit d’outre-mer, et qui s’expriment à travers des langues différentes. -

Painting Outside the Lines: How Daoism Shaped

PAINTING OUTSIDE THE LINES: HOW DAOISM SHAPED CONCEPTIONS OF ARTISTIC EXCELLENCE IN MEDIEVAL CHINA, 800–1200 A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN RELIGION (ASIAN) AUGUST 2012 By Aaron Reich Thesis Committee: Poul Andersen, Chairperson James Frankel Kate Lingley Acknowledgements Though the work on this thesis was largely carried out between 2010–2012, my interest in the religious aspects of Chinese painting began several years prior. In the fall of 2007, my mentor Professor Poul Andersen introduced me to his research into the inspirational relationship between Daoist ritual and religious painting in the case of Wu Daozi, the most esteemed Tang dynasty painter of religious art. Taken by a newfound fascination with this topic, I began to explore the pioneering translations of Chinese painting texts for a graduate seminar on ritual theory, and in them I found a world of potential material ripe for analysis within the framework of religious studies. I devoted the following two years to intensive Chinese language study in Taiwan, where I had the fortuitous opportunity to make frequent visits to view the paintings on exhibit at the National Palace Museum in Taipei. Once I had acquired the ability to work through primary sources, I returned to Honolulu to continue my study of literary Chinese and begin my exploration into the texts that ultimately led to the central discoveries within this thesis. This work would not have been possible without the sincere care and unwavering support of the many individuals who helped me bring it to fruition. -

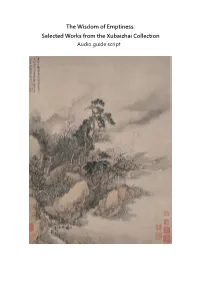

The Wisdom of Emptiness: Selected Works from the Xubaizhai Collection Audio Guide Script

The Wisdom of Emptiness: Selected Works from the Xubaizhai Collection Audio guide script 400 Exhibition overview Welcome to “The Wisdom of Emptiness: Selected Works from the Xubaizhai Collection” exhibition. Xubaizhai was designated by the late collector of Chinese painting and calligraphy, Mr Low Chuck-tiew. A particular strength of the collection lies in the Ming and Qing dynasties works by masters of the “Wu School”, “Songjiang School”, “Four Monks”, “Orthodox School” and “Eight Eccentrics of Yangzhou”. This exhibition features more than 30 representative works from the Ming and Qing dynasties to the twentieth century. This audio guide will take you through highlighted pieces in the exhibition, as well as the artistic characteristics of different schools of painting and individual artists. 401.Exhibit no. 1 Shen Zhou (1427 – 1509) Farewell by a stream at the end of the year 1486 Hanging scroll, ink and colour on paper 143 x 62.5 cm Xubaizhai Collection Shen Zhou, courtesy name Qinan, was a native of Suzhou in Jiangsu province. He excelled in painting and poetry as well as calligraphy, in which he followed the style of Huang Tingjian (1045 – 1105), while his students included Wen Zhengming (1470 – 1559) and Tang Yin (1470 – 1524). Shen was hailed as the most prominent master of the Wu School of Painting and one of the Four Masters of the Ming dynasty (1368 – 1644). Studying under Chen Kuan (ca. 1393 – 1473), Du Qiong (1396 – 1474) and Liu Jue (1410 – 1472), Shen modelled his paintings on the styles of Wang Fu (1362 – 1416) and the Four Masters of the Yuan dynasty (1279 – 1368), but he also extended his interest to the works of the Zhe School and incorporated its techniques into his art. -

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-02450-2 — Art and Artists in China Since 1949 Ying Yi , in Collaboration with Xiaobing Tang Index More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-02450-2 — Art and Artists in China since 1949 Ying Yi , In collaboration with Xiaobing Tang Index More Information Index Note: The artworks illustrated in this book are oil paintings unless otherwise stated. Figures 1–33 will be found in Plate section 1 (between pp. 49 and 72); Figures 34–62 in section 2 (between pp. 113 and 136); Figures 63–103 in section 3 (between pp. 199 and 238); Figures 104–161 in section 4 (between pp. 295 and 350). abstract art (Chinese) 163, 269–274, art market see commercialization of art 279 art publications (new) 86, 165–172 early 1980s 269–271 Artillery of the October Revolution 42 ’85 Movement –“China/Avant-Garde” Arts and Craft Movement 268 269–271 Attacking the Headquarters (Fig. 27) 1989 – present (post-modern) stage 273 avant-garde art (Chinese) 141, 146, 169, conceptual abstraction 273–274, 277–278 176, 181, 239, 245, 258, 264–265 expressive abstraction 273–274, 276 see also “China/Avant-Garde” material abstraction 277 exhibition schematic abstraction 245, 274 avant-garde art (Russian) 3–4 abstract art (Western) 147–148, 195–196, avant-garde art (Western) 100, 101, 267–268 see also Abstract 255–256, 257, 264 see also Modernism Expressionism; Hard-Edge / Structural Abstraction Bacon, Francis 243 Abstract Expressionism 256, 269, 274 Bao Jianfei 172 academic realism 245, 270 New Space No.1 167 academies see art academies Barbizon School 87 Ai Xinzhong 14 Bauhaus School 269 Ai Zhongxin 5 Beckmann, Max 246 amateur art/artists 35, 74–75, 106–108, Bei Dao 140 137–138, 141,