Florida Historical Quarterly

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Central Kansas Flywheels, Inc

A Living History Museum Central Kansas flywheels YESTERYEAR MUSEUM 2014 2ND QUARTER NEWSLETTER VOLUMN 30, ISSUE 2 FROM THE OFFICE / Submitted by Will Cooper 2014 BOARD OF DIRECTORS BASKETS OFFICERS During the fall show (October 11th) we will be selling chances for the Op- portunity Baskets again this year. We would appreciate it if all members or President: Joan Caldwell Vice-President: Tom Caldwell members wives would donate a basket. Secretary: Will Cooper Treasurer: Dave Brenda Tonniges Ideas for baskets are: children’s items, school items, Halloween items, pet baskets, baby items, coffee baskets, or most anything. DIRECTORS 2016 If you do not have a basket for the container use a box covered with paper or foil. Hank Boyer Brad Yost They need to be delivered to the office the week of October 7th. Katie Reiss 2015 Also, cakes, brownies, or cupcakes are need October 11th for the cake walk. Marilyn Marietta Anyone that would like to volunteer for the Antique Engine and Steam Show Chris Housos are encouraged to call the office at 825-8743 and let us know what would Anthony Reiss Gary Hicks interest you during the show. If you have the time but are not sure what you would like to do, we would be more than happy place you in an area of need. 2014 This is a chance to help promote the museum to the public and leave a lasting Jerry May impression on all the visitors. Ron Sutton John Thelander Bryan Lorenson EVENTS AND HAPPENINGS/ Submitted by Will Cooper The museum hosted a three day Cub Scout Day camp on June 26, 27 & 28. -

Snyder, Robert Mcclure, Jr. (1876-1937), Papers, 1890-1937 3524 3.6 Cubic Feet

C Snyder, Robert McClure, Jr. (1876-1937), Papers, 1890-1937 3524 3.6 cubic feet This collection is available at The State Historical Society of Missouri. If you would like more information, please contact us at [email protected]. INTRODUCTION Correspondence, historical notes, book lists, and photographs of Snyder, joint heir of the Ozark Hahatonka estate, collector of rare books, and writer on many phases of western history, especially Kansas City, MO, and vicinity. DONOR INFORMATION The papers were donated to the State Historical Society of Missouri by William K. Snyder on 19 Aug 1968 (Accession No. 0564). SCOPE AND CONTENT NOTE Please See Folder List. FOLDER LIST f. 1-13 Personal Papers. Synder family history, including Robert M. Snyder, Jr.’s school, college and travel notes and photographs. f. 8 Newspaper accounts of Robert M. Snyder's death in Kansas City in 1937. f. 9-11 Papers pertaining to the family business, the Kansas City Natural Gas Company. f. 12 Miscellaneous business papers including some expenditures for Hahatonka estate and other receipts. L_____ f. 14-38 Hahatonka. History of the Missouri Ozark estate owned by the Snyder family, photographs of the castle, articles, correspondence and notes on the law suit resulting from Union Electric Company's construction of Bagnell Dam. f. 32 Crawfish business f. 33-38 Snyder Estate vs. Union Electric Company, legal papers. f. 39-75 Missouriana. Alphabetically arranged history of early settlers, places, and culture of Missouri compiled from books, notes, maps, and newspapers. Includes Missouri Indian tribes, Ozark literature, early churches and schools, book lists, and historical personages. -

The Kanza-Who, Where and When? a Teaching/Study Unit on the Kanza People of the Kaw Nation

The Kanza-Who, Where and When? A teaching/study unit on the Kanza People of the Kaw Nation This multi-day teaching/learning unit over the Kanza or Kaw Nation will provide a condensed overview of the history of the Kanza people that middle and secondary students could easily read in a class period and will provide teaching strategies, classroom activities and additional resources to use to expand the study into several days. Unit assembled by Dr. Tim Fry, Washburn University, October 2018. Goals/objectives of the unit: 1) The student will be able to place and label important dates in Kanza history on a timeline. Specifically be able to add the following important dates and label each date with an identifying word or phrase on the timeline: 1724, 1825, 1830, 1846, 1859, 1873, 1902, 1922, 1928, 1959, 2000 2) The student will be able to locate and/or label significant geographical places on a map that were important in the history of the Kanza People. Specifically be able to locate if labeled or label if not labeled for the following: Missouri River, the Kansas or Kaw River, Blue River, Neosho River, the Arkansas River, the location of modern-day Kansas City, Topeka, Manhattan, Council Grove and Kay County, Oklahoma. In addition be able to the label major dwelling/living locations for the Kanza in the 1700s, where they lived from 1825 to 1846, where they lived from 1846 to 1873 and where the majority of Kanza people live today. 3) The student will be able to describe some important events in the history of the Kanza and identify/note some contributions of several important individuals to the story of the Kaw Nation. -

Tribes of Oklahoma – Request for Information for Teachers (Common Core State Standards for Social Studies, OSDE)

Tribes of Oklahoma – Request for Information for Teachers (Common Core State Standards for Social Studies, OSDE) Tribe:__Kaw Nation (it was that Koln-Za or Kanza became phoneticized by first the French, then the English to Kansas and Kaw.) Tribal websites(s) http//kawnation.com 1. Migration/movement/forced removal Oklahoma History C3 Standard 2.3 “Integrate visual and textual evidence to explain the reasons for and trace the migrations of Native American peoples including the Five Tribes into present-day Oklahoma, the Indian Removal Act of 1830, and tribal resistance to the forced relocations.” Historians and ethno historians have determined that the Kaw, Osage, Ponca, Omaha, and Quapaw — technically known as the Dhegiha-Siouan division of the Hopewell cultures of the lower Ohio Valley — lived together as one people in the lower Ohio valley prior to the white invasion of North American in the late 15th century. Sometime prior to about 1750, the search for better sources of game and pressure from the more powerful Algonquians to the east prompted a westward migration to the mouth of the Ohio River. The Quapaws continued down the Mississippi River and took the name “downstream people” while the Kaw, Osage, Ponca, and Omaha — the “upstream people” — moved to the mouth of the Missouri near present-day St. Louis, up the Missouri to the mouth of the Osage River, where another division took place. The Ponca and Omaha moved northwest to present-day eastern Nebraska, the Osage occupied the Ozark country to the southwest, and the Kaws assumed control of the region in and around present-day Kansas City as well as the Kansas River Valley to the west. -

Upk Olson.Indd

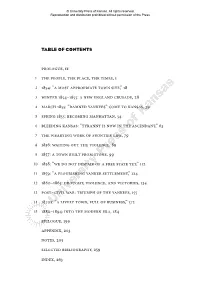

© University Press of Kansas. All rights reserved. Reproduction and distribution prohibited without permission of the Press. table oF ContentS prologue, ix 1 the people, the place, the times, 1 2 1854: “a most appropriate town site,” 18 3 winter 1854–1855: a new england crusade, 28 4 march 1855: “damned yankees” come to kansas, 39 5 spring 1855: becoming manhattan, 54 6 bleeding kansas: “tyranny is now in the ascendant,” 63 7 the wearying work of frontier life, 79 8 1856: waiting out the violence, 89 9 1857: a town built from stone, 99 10 1858: “we do not despair of a free state yet,” 112 11 1859: “a flourishing yankee settlement,” 124 12 1860–1865: drought, violence, and victories, 134 13 post–civil war: triumph of the yankees, 155 14 1870s: “a lively town, full of business,” 172 15 1880–1894: into the modern era, 184 epilogue, 199 appendix, 203 notes, 205 selected bibliography, 259 index, 263 © University Press of Kansas. All rights reserved. Reproduction and distribution prohibited without permission of the Press. © University Press of Kansas. All rights reserved. Reproduction and distribution prohibited without permission of the Press. ProloGUe On a frosty afternoon in Kansas Territory on March 27, 1855, a stern Rhode Island abolitionist named Isaac Goodnow and five other New Englanders wrestled a bulky canvas tent into shape in a tallgrass prairie at the junction of the Kansas and Big Blue rivers. The prairie was colder than Goodnow had imagined it would be in late March. But he and his party were in good spirits as they moved mattresses and supplies from the wagon into their campsite: the men had finally reached their destination after a three-week trip from Boston, covering 1,500 miles, capped by a struggle to get their overburdened covered wagon through the snowstorms and icy riv- ers of Kansas Territory. -

Maryland-North Caroline

Maryland 883 The greater part of these arms were issued to Volunteer Militia companies outside of Baltimore,usingthewarehouseofwoolford&Pattersoninthatcityasadistributionpoint.On 19 April 1861 this warehouse was broken into by a pro-Southern Baltimore mob and everything there taken-some 370 infantry muskets and a small number of cavalry arms and accouterments.TheseweaponswereusedtodispersetheWashingtonBrigadeofPhiladelphia when that unamed and hapless command tried to march through Baltimore. Some of the weapons in the hands of the Baltimore Volunteer companies found their way into Virginia, and most of the remainder were seized on the govemor's orders in June. This forestalled any large shipments of small amis to Marylanders in the Confederate army and providedasmallstockforthenewregimentsbeingraised.Thereafterthestateappearstohave played no part in procuring arms for its volunteer and home guard commands save through U.S. Amy sources. It ended the war with little or no stock of serviceable shoulder arms. During the reorganization of 1867 the state was obliged to purchase ams for its new MarylandNationalGuardinadditiontothefieldartillerymaterialitobtainedfromthegeneral government. The small arms and related accouterments secured were: 7,943 U.S. rifle muskets (Model 1863?) 7,354 sets infantry belts and boxes 3,000 cavalry sabers (Model 1860?) 3 ,OcO cavalry waist belts 500 light artillery sabers 500 light artillery waist belts All these items were U.S. regulation patterns, including the belt plates. All were won until after 1872, when our period ends. 2+ 'usA mqulc~d zS <¢.A i;I`^r_tl!to_/ . ORDER OF BATTLE: VOLUNTEER MILITIA I st Light Division (Baltimore) `. lstRegtcav / C)a/cJ Comps distinctively dressed. Had a mounted band. 1~ lst Regt Art)r (consol 1860 with City Guard Bn) 2C) No information on equipage. -

October 4–6 Deadwood | Sdbookfestival.Com

October 4–6 Deadwood | sdbookfestival.com CONTENTS 4 Mayor’s Welcome 6 SD Humanities Council Welcome 7 Event Locations and Parking 8 A Tribute to Children’s and Y.A. Literature Sponsored by Black Hills Reads, First Bank & Trust, Northern Hills Federal Credit Union and John T. Vucurevich Foundation 9 A Tribute to Fiction Sponsored by AWC Family Foundation and Larson Family Foundation 10 A Tribute to Poetry Sponsored by Brass Family Foundation 11 A Tribute to Non-Fiction Sponsored by Midco and South Dakota Public Broadcasting 12 A Tribute to Writers’ Support Sponsored by Sandra Brannan and South Dakota Arts Council 13 A Tribute to History and Tribal Writing Sponsored by Home Slice Media and City of Deadwood 14 Presenters 24 Schedule of Events 30 Exhibitors’ Hall For more information visit sdbookfestival.com or call (605) 688-6113. Times and presenters listed are subject to change. Watch for changes on sdbookfestival.com, twitter.com/sdhumanities, facebook.com/sdhumanities and in the Festival Updates Bulletin, a handout available at the Exhibitors’ Hall information desk in the Deadwood Mountain Grand Event Center. The South Dakota Festival of Books guide is a publication of 410 E. Third St. • Yankton, SD 57078 800-456-5117 • www.SouthDakotaMagazine.com 3 WELCOME... HAVE THE PRIVILEGE as mayor of the city of Deadwood to welcome you to our community for the 17th annual South I Dakota Festival of Books. Since the inception of this event in 2003, Deadwood has hosted the Festival each odd- numbered year. The City of Deadwood, Deadwood Historic Preservation Commission and the Deadwood City Library are pleased to partner with the South Dakota Humanities Council to present this book festival. -

Tribal Perspectives/Great Plains Teacher Guide and Appendices

Tribal Perspectives on American History Volume II Great Plains Upper Missouri Basin Native Voices DVD & Teacher Guide :: Grades 7-12 First Edition by Sally Thompson, Happy Avery, Kim Lugthart, Elizabeth Sperry The Regional Learning Project collaborates with North American tribal educators to produce archival quality, primary resource materials about northwestern Native Americans and their histories. © 2009 Regional Learning Project, University of Montana, Center for Continuing Education Regional Learning Project at the University of Montana–Missoula grants teachers permission to photocopy the activity pages from this book for classroom use. No other part of this publication may be reproduced in whole or in part, or stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without written permission of the publisher. For more information regarding permission, write to: Regional Learning Project, UM Continuing Education, Missoula, MT 59812. UM Regional Learning Project Tribal Perspectives on American History Series Vol. I • Northwest (2008) Vol. II • Great Plains – Upper Missouri Basin (2009) Acknowledgments We thank the following tribal members for the invaluable contributions of theirwisdom and experience which have made this guide possible: Richard Antelope (Arapaho) Starr Weed (Eastern Shoshone) Hubert Friday (Arapaho) Sean Chandler (Gros Ventre) Loren Yellow Bird (Arikara) Everall Fox (Gros Ventre) Robert Four Star (Assiniboine) George Horse Capture (Gros -

Uniforms at Fort Mchenry, 1814

rowebsI FORM 10-23 Rev Oct 61 UNITED STATES CREr ooieq 44Q DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR SLK/5t NATIONAL PARK SERVICE cm Fort McHenry NM US Park or Office -Iw Historian Gregorio Carrera rn xl I. CA rt 11 Pt CD Pt Co P-a PLEASE RETURN THIS FILE PROMPTLY TO Research and Interpretation Activity IMPORTANT This file constitutes port of the official records of the FROM Notional Pork Service and should not be or separated papers Date withdrawn without express authority of the official in charge Officials and employees will be held responsible for failure to observe these rules which are necessary to pro TO tect the integrity of the official records Dote UNIPORNS AT PORT MCIIENRY 1814 Fort lidilenry National Horniment and Historic Shrine Gregorio Carrera Historian July 1963 PREFACK The purpose of this paper is to pull together all information on uniforms of all units both regular and militia involved in the defense of Fort Mdllenry September 13-14 1814 Such information is scant and fragmented and it is hoped this work is complete 1his paper is truly cooperative effort Material was collected by the Historical and Archeological Research Projects and by other historians at Fort Mclienry Sole responsibtlity for compiling this information is mine ii TABLE OF CONtENTS Page Preface ii lntrcductiott Chapter WhoWasHsreInl8l4 Chapter II Captains Evans Company iT Regular Artillery and The 12th 14th 36th and 38th Regiments Regular Infantry Chapter The MarylandNilitiaArtillery 10 Chapter IV The Navy 14 Chapter The Sea Fencibles 18 Chapter VI Conclusions 19 Footnotes -

United States of America Nuclear Regulatory Commission

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA NUCLEAR REGULATORY COMMISSION COMMISSIONERS: Gregory B. Jaczko, Chairman Peter B. Lyons Dale E. Klein Kristine L. Svinicki _________________________________________ In the Matter of ) ) Docket No. 40-8943-MLA CROW BUTTE RESOURCES, INC. ) ) (North Trend Expansion Area) ) _________________________________________) CLI-09-12 MEMORANDUM AND ORDER Today we consider appeals by the NRC Staff and the applicant, Crow Butte Resources, Inc. (Crow Butte) of two Atomic Safety and Licensing Board decisions. The NRC Staff and Crow Butte appeal LBP-08-6, granting a hearing to several petitioners with respect to Crow Butte’s license amendment application.1 The Staff and Crow Butte further appeal LBP-09-1, which admitted a contention relating to Crow Butte’s ownership by a foreign parent corporation, and which also added a new basis relating to the health effects of arsenic to a previously admitted contention.2 We affirm, in part, the Board’s grant of a hearing on Contentions A and B, and reformulate the revised contention accordingly. We reverse the Board’s decision to admit 1 LBP-08-6, 67 NRC 241 (2008). 2 LBP-09-1, 69 NRC __ (Jan. 27, 2009)(slip op.). - 2 - Contention C, relating to the consultations with Indian Tribes, and Contention E, relating to the applicant’s foreign ownership. In addition, we reverse the Board’s decision to admit a new basis, relating to the health effects of arsenic exposure, to previously admitted Contention B. Finally, we decline to direct the Board to apply the formal hearing procedures of 10 C.F.R. Part 2, Subpart G, to this matter. -

Fading Roles of Fictive Kinship: Mixed-Blood Racial Isolation and United States Indian Policy in the Lower Missouri River Basin, 1790-1830

FADING ROLES OF FICTIVE KINSHIP: MIXED-BLOOD RACIAL ISOLATION AND UNITED STATES INDIAN POLICY IN THE LOWER MISSOURI RIVER BASIN, 1790-1830 by ZACHARY CHARLES ISENHOWER B.A., Kansas State University, 2009 A THESIS submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF ARTS Department of History College of Arts and Sciences KANSAS STATE UNIVERSITY Manhattan, Kansas 2012 Approved by: Major Professor Charles W. Sanders, Jr. Copyright ZACHARY CHARLES ISENHOWER 2012 Abstract On June 3, 1825, William Clark, Superintendent of Indian Affairs, and eleven representatives of the “Kanzas” nation signed a treaty ceding their lands to the United States. The first to sign was “Nom-pa-wa-rah,” the overall Kansa leader, better known as White Plume. His participation illustrated the racial chasm that had opened between Native- and Anglo- American worlds. The treaty was designed to ease pressures of proximity in Missouri and relocate multiple nations West of the Mississippi, where they believed they would finally be beyond the American lust for land. White Plume knew different. Through experience with U.S. Indian policy, he understood that land cessions only restarted a cycle of events culminating in more land cessions. His identity as a mixed-blood, by virtue of the Indian-white ancestry of many of his family, opened opportunities for that experience. Thus, he attempted in 1825 to use U.S. laws and relationships with officials such as William Clark to protect the future of the Kansa. The treaty was a cession of land to satisfy conflicts, but also a guarantee of reserved land, and significantly, of a “half- breed” tract for mixed-blood members of the Kansa Nation. -

Visit to Blue Earth Village by Lauren W

Illustration of the Kanza Blue Earth village in 1819 from the sketchbook of Titian Ramsay Peale. Courtesy of the Yale University Art Gallery. Kansas History: A Journal of the Central Plains 38 (Spring 2015): 2–21 2 Kansas History Visit to Blue Earth Village by Lauren W. Ritterbush fter two weeks of grueling overland travel during the hot month of August, thirteen exhausted Americans espied their destination, the village of the Kanza Indian tribe near the Big Blue and Kansas Rivers.1 Not knowing whether they would be received as friends or foes, they stopped to hoist a flag and prepare themselves by “arrang[ing] their dress, and inspect[ing] their firearms.” Once they were sighted, “the [Kanza] Women & Children went to the tops of their Houses with bits of Looking Glass and tin to reflect the light on Athe Party approaching.” In turn, a mob of “chiefs and warriors came rushing out on horseback, painted and decorated, and followed by great numbers on foot.” This was the point at which their fate among the Kanzas would be known. “The chief who was in advance, halted his horse when within a few paces of us; surveyed us sternly and attentively for some moments, and then offered his hand.” Only then could the Americans breathe a sigh of relief and accept the many greetings that followed. Despite the friendly welcome, the party of weary travelers undoubtedly felt overwhelmed as they were engulfed by a throng of Indians. Under the influence of prominent Kanza men, the crowd parted, allowing the visitors to enter the village and the home of a principal leader of the tribe.