Whataboutisms

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Online Russia, Today

Online Russia, today. How is Russia Today framing the events of the Ukrainian crisis of 2013 and what this framing says about the Russian regime’s legitimation strategies? The case of the Russian-language online platform of RT Margarita Kurdalanova 24th of June 2016 Graduate School of Social Sciences Authoritarianism in a Global Age Adele Del Sordi Dr. Andrey Demidov This page intentionally left blank Word count: 14 886 1 Table of Contents Abstract ...................................................................................................................................... 3 1.Introduction ............................................................................................................................. 4 2.Literature Review .................................................................................................................... 5 2.1 Legitimacy and legitimation ............................................................................................. 5 2.2. Legitimation in authoritarian regimes ............................................................................. 7 2.3 Media and authoritarianism .............................................................................................. 9 2.4 Propaganda and information warfare ............................................................................. 11 3.Case study ............................................................................................................................. 13 3.1 The Russian-Ukrainian conflict of 2013 ....................................................................... -

Fallacies Mini Project

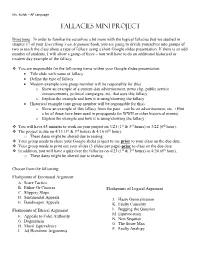

Ms. Kizlyk – AP Language Fallacies Mini Project Directions: In order to familiarize ourselves a bit more with the logical fallacies that we studied in chapter 17 of your Everything’s an Argument book, you are going to divide yourselves into groups of two to teach the class about a type of fallacy using a short Google slides presentation. If there is an odd number of students, I will allow a group of three – you will have to do an additional historical or modern day example of the fallacy. You are responsible for the following items within your Google slides presentation: Title slide with name of fallacy Define the type of fallacy Modern example (one group member will be responsible for this) o Show an example of a current-day advertisement, news clip, public service announcements, political campaigns, etc. that uses this fallacy o Explain the example and how it is using/showing the fallacy Historical example (one group member will be responsible for this) o Show an example of this fallacy from the past – can be an advertisement, etc. (Hint – a lot of these have been used in propaganda for WWII or other historical events). o Explain the example and how it is using/showing the fallacy You will have 45 minutes to work on your project on 3/21 (1st & 3rd hours) or 3/22 (6th hour). The project is due on 4/13 (1st & 3rd hours) & 4/16 (6th hour). o These dates might be altered due to testing. Your group needs to share your Google slides project to me prior to your class on the due date. -

Argumentation and Fallacies in Creationist Writings Against Evolutionary Theory Petteri Nieminen1,2* and Anne-Mari Mustonen1

Nieminen and Mustonen Evolution: Education and Outreach 2014, 7:11 http://www.evolution-outreach.com/content/7/1/11 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Argumentation and fallacies in creationist writings against evolutionary theory Petteri Nieminen1,2* and Anne-Mari Mustonen1 Abstract Background: The creationist–evolutionist conflict is perhaps the most significant example of a debate about a well-supported scientific theory not readily accepted by the public. Methods: We analyzed creationist texts according to type (young earth creationism, old earth creationism or intelligent design) and context (with or without discussion of “scientific” data). Results: The analysis revealed numerous fallacies including the direct ad hominem—portraying evolutionists as racists, unreliable or gullible—and the indirect ad hominem, where evolutionists are accused of breaking the rules of debate that they themselves have dictated. Poisoning the well fallacy stated that evolutionists would not consider supernatural explanations in any situation due to their pre-existing refusal of theism. Appeals to consequences and guilt by association linked evolutionary theory to atrocities, and slippery slopes to abortion, euthanasia and genocide. False dilemmas, hasty generalizations and straw man fallacies were also common. The prevalence of these fallacies was equal in young earth creationism and intelligent design/old earth creationism. The direct and indirect ad hominem were also prevalent in pro-evolutionary texts. Conclusions: While the fallacious arguments are irrelevant when discussing evolutionary theory from the scientific point of view, they can be effective for the reception of creationist claims, especially if the audience has biases. Thus, the recognition of these fallacies and their dismissal as irrelevant should be accompanied by attempts to avoid counter-fallacies and by the recognition of the context, in which the fallacies are presented. -

Framing Environmental Movements: a Multidisciplinary Analysis of the Anti-Plastic Straw Movement

Framing Environmental Movements: A Multidisciplinary Analysis of the Anti-Plastic Straw Movement MPP Professional Paper In Partial Fulfillment of the Master of Public Policy Degree Requirements The Hubert H. Humphrey School of Public Affairs The University of Minnesota Caroline Arkesteyn 5/1/2020 Peter Calow, Professor Mark Pedelty, Professor _______________________________ ________________________________________ Typed Name & Title, Paper Supervisor Typed Name & Title, Second Committee Member ` FRAMING ENVIRONMENTAL MOVEMENTS A Multidisciplinary Analysis of the Anti-Plastic Straw Movement Caroline Arkesteyn Humphrey School of Public Affairs | University of Minnesota Table of Contents 1. Introduction 2. Literature Review 2.1. The Public Policy Process 2.2. Social Movements Theory 2.3. Framing Theory 3. The Movement 3.1. The Environmental Issue 3.2. Spurring Event 3.3. Social Media Trajectory 3.4. Issue Framing 3.4.1. Frames Used by Supporters 3.4.2. Frames Used by Critics 3.4.3. Message and Participant Motivation 3.5. Industry Response 3.6. Policy Response 3.6.1. Seattle 3.6.2. California 3.6.3. New York City 3.6.4. United Kingdom 3.7. Critiques 4. Conclusions and Recommendations 4.1. Policy Recommendations 4.1.1. Investing in Recycling Technology and Infrastructure 4.1.2. Implementing a “Producer-Pays” Fee on Single-Use Plastics 4.1.3. Expanding Environmental Education 4.2. Communications Recommendations 4.2.1. Systems-Focused Language 4.2.2. Highlighting Agency 4.2.3. Social Media Communication and Agenda-Setting 5. Implications and Future Research 1 I. INTRODUCTION In the late months of 2017, a new viral message began circulating social media platforms. -

Download Full Journal (PDF)

SAPIR A JOURNAL OF JEWISH CONVERSATIONS THE ISSUE ON POWER ELISA SPUNGEN BILDNER & ROBERT BILDNER RUTH CALDERON · MONA CHAREN MARK DUBOWITZ · DORE GOLD FELICIA HERMAN · BENNY MORRIS MICHAEL OREN · ANSHEL PFEFFER THANE ROSENBAUM · JONATHAN D. SARNA MEIR SOLOVEICHIK · BRET STEPHENS JEFF SWARTZ · RUTH R. WISSE Volume Two Summer 2021 And they saw the God of Israel: Under His feet there was the likeness of a pavement of sapphire, like the very sky for purity. — Exodus 24: 10 SAPIR Bret Stephens EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Mark Charendoff PUBLISHER Ariella Saperstein ASSO CIATE PUBLISHER Felicia Herman MANAGING EDITOR Katherine Messenger DESIGNER & ILLUSTRATOR Sapir, a Journal of Jewish Conversations. ISSN 2767-1712. 2021, Volume 2. Published by Maimonides Fund. Copyright ©2021 by Maimonides Fund. No part of this journal may be reproduced in any form or by any means without the prior written consent of Maimonides Fund. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. WWW.SAPIRJOURNAL.ORG WWW.MAIMONIDESFUND.ORG CONTENTS 6 Publisher’s Note | Mark Charendoff 90 MICHAEL OREN Trial and Triage in Washington 8 BRET STEPHENS The Necessity of Jewish Power 98 MONA CHAREN Between Hostile and Crazy: Jews and the Two Parties Power in Jewish Text & History 106 MARK DUBOWITZ How to Use Antisemitism Against Antisemites 20 RUTH R. WISSE The Allure of Powerlessness Power in Culture & Philanthropy 34 RUTH CALDERON King David and the Messiness of Power 116 JEFF SWARTZ Philanthropy Is Not Enough 46 RABBI MEIR Y. SOLOVEICHIK The Power of the Mob in an Unforgiving Age 124 ELISA SPUNGEN BILDNER & ROBERT BILDNER Power and Ethics in Jewish Philanthropy 56 ANSHEL PFEFFER The Use and Abuse of Jewish Power 134 JONATHAN D. -

FAKE NEWS!”: President Trump’S Campaign Against the Media on @Realdonaldtrump and Reactions to It on Twitter

“FAKE NEWS!”: President Trump’s Campaign Against the Media on @realdonaldtrump and Reactions To It on Twitter A PEORIA Project White Paper Michael Cornfield GWU Graduate School of Political Management [email protected] April 10, 2019 This report was made possible by a generous grant from William Madway. SUMMARY: This white paper examines President Trump’s campaign to fan distrust of the news media (Fox News excepted) through his tweeting of the phrase “Fake News (Media).” The report identifies and illustrates eight delegitimation techniques found in the twenty-five most retweeted Trump tweets containing that phrase between January 1, 2017 and August 31, 2018. The report also looks at direct responses and public reactions to those tweets, as found respectively on the comment thread at @realdonaldtrump and in random samples (N = 2500) of US computer-based tweets containing the term on the days in that time period of his most retweeted “Fake News” tweets. Along with the high percentage of retweets built into this search, the sample exhibits techniques and patterns of response which are identified and illustrated. The main findings: ● The term “fake news” emerged in public usage in October 2016 to describe hoaxes, rumors, and false alarms, primarily in connection with the Trump-Clinton presidential contest and its electoral result. ● President-elect Trump adopted the term, intensified it into “Fake News,” and directed it at “Fake News Media” starting in December 2016-January 2017. 1 ● Subsequently, the term has been used on Twitter largely in relation to Trump tweets that deploy it. In other words, “Fake News” rarely appears on Twitter referring to something other than what Trump is tweeting about. -

Useful Argumentative Essay Words and Phrases

Useful Argumentative Essay Words and Phrases Examples of Argumentative Language Below are examples of signposts that are used in argumentative essays. Signposts enable the reader to follow our arguments easily. When pointing out opposing arguments (Cons): Opponents of this idea claim/maintain that… Those who disagree/ are against these ideas may say/ assert that… Some people may disagree with this idea, Some people may say that…however… When stating specifically why they think like that: They claim that…since… Reaching the turning point: However, But On the other hand, When refuting the opposing idea, we may use the following strategies: compromise but prove their argument is not powerful enough: - They have a point in thinking like that. - To a certain extent they are right. completely disagree: - After seeing this evidence, there is no way we can agree with this idea. say that their argument is irrelevant to the topic: - Their argument is irrelevant to the topic. Signposting sentences What are signposting sentences? Signposting sentences explain the logic of your argument. They tell the reader what you are going to do at key points in your assignment. They are most useful when used in the following places: In the introduction At the beginning of a paragraph which develops a new idea At the beginning of a paragraph which expands on a previous idea At the beginning of a paragraph which offers a contrasting viewpoint At the end of a paragraph to sum up an idea In the conclusion A table of signposting stems: These should be used as a guide and as a way to get you thinking about how you present the thread of your argument. -

The “Ambiguity” Fallacy

\\jciprod01\productn\G\GWN\88-5\GWN502.txt unknown Seq: 1 2-SEP-20 11:10 The “Ambiguity” Fallacy Ryan D. Doerfler* ABSTRACT This Essay considers a popular, deceptively simple argument against the lawfulness of Chevron. As it explains, the argument appears to trade on an ambiguity in the term “ambiguity”—and does so in a way that reveals a mis- match between Chevron criticism and the larger jurisprudence of Chevron critics. TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ................................................. 1110 R I. THE ARGUMENT ........................................ 1111 R II. THE AMBIGUITY OF “AMBIGUITY” ..................... 1112 R III. “AMBIGUITY” IN CHEVRON ............................. 1114 R IV. RESOLVING “AMBIGUITY” .............................. 1114 R V. JUDGES AS UMPIRES .................................... 1117 R CONCLUSION ................................................... 1120 R INTRODUCTION Along with other, more complicated arguments, Chevron1 critics offer a simple inference. It starts with the premise, drawn from Mar- bury,2 that courts must interpret statutes independently. To this, critics add, channeling James Madison, that interpreting statutes inevitably requires courts to resolve statutory ambiguity. And from these two seemingly uncontroversial premises, Chevron critics then infer that deferring to an agency’s resolution of some statutory ambiguity would involve an abdication of the judicial role—after all, resolving statutory ambiguity independently is what judges are supposed to do, and defer- ence (as contrasted with respect3) is the opposite of independence. As this Essay explains, this simple inference appears fallacious upon inspection. The reason is that a key term in the inference, “ambi- guity,” is critically ambiguous, and critics seem to slide between one sense of “ambiguity” in the second premise of the argument and an- * Professor of Law, Herbert and Marjorie Fried Research Scholar, The University of Chi- cago Law School. -

Begging the Question/Circular Reasoning Caitlyn Nunn, Chloe Christensen, Reece Taylor, and Jade Ballard Definition

Begging the Question/Circular Reasoning Caitlyn Nunn, Chloe Christensen, Reece Taylor, and Jade Ballard Definition ● A (normally) comical fallacy in which a proposition is backed by a premise or premises that are backed by the same proposition. Thus creating a cycle where no new or useful information is shared. Universal Example ● “Pvt. Joe Bowers: What are these electrolytes? Do you even know? Secretary of State: They're... what they use to make Brawndo! Pvt. Joe Bowers: But why do they use them to make Brawndo? Secretary of Defense: [raises hand after a pause] Because Brawndo's got electrolytes” (Example from logically fallicious.com from the movie Idiocracy). Circular Reasoning in The Crucible Quote: One committing the fallacy: Elizabeth Hale: But, woman, you do believe there are witches in- Explanation: Elizabeth believes that Elizabeth: If you think that I am one, there are no witches in Salem because then I say there are none. she knows that she is not a witch. She doesn’t think that she’s a witch (p. 200, act 2, lines 65-68) because she doesn’t believe that there are witches in Salem. And so on. More examples from The Crucible Quote: One committing the fallacy: Martha Martha Corey: I am innocent to a witch. I know not what a witch is. Explanation: This conversation Hawthorne: How do you know, then, between Martha and Hathorne is an that you are not a witch? example of begging the question. In Martha Corey: If I were, I would know it. Martha’s answer to Judge Hathorne, she uses false logic. -

RESEARCH and REPORT by Greenberg Quinlan Rosner Research and Echelon Insights for the Reporters Committee for Freedom for the Press and the Democracy Fund

RESEARCH AND REPORT BY Greenberg Quinlan Rosner Research and Echelon Insights for the Reporters Committee for Freedom for the Press and the Democracy Fund PRESS FREEDOM FOR THE PEOPLE 1 Table of contents Foreword 2 Key Findings 4 Trust in National Media 5 Regaining Trust 7 Appendix A: Media Sources 21 Appendix B: Media Doubts and Facts 24 __________________________ ã2018 All Rights Reserved, Greenberg Quinlan Rosner PRESS FREEDOM FOR THE PEOPLE 2 Foreword By Jenn topper communications director, reporters committee for freedom of the press A robust free press is vital to an informed public. It’s with that in mind that we sought to understand the public’s perceptions of press freedom at a moment in time when trust in the press remains low, and when the president of the United States regularly deems members of the press “enemy of the people” and refers to entire news organizations as “fake news.” The research took on even more significance after the murder of four journalists and one sales assistant at the Capital Gazette in Annapolis, Maryland, by a gunman who had a long history of making threats against the newspaper. We learned, through a series of focus groups and a 2,000-voter survey, that there is a lack of urgency around the idea that press freedom is at risk here in the U.S. Press freedom advocates see an alarming confluence of threats to journalists and the news media, including harmful rhetoric emanating from ã2018 All Rights Reserved, Greenberg Quinlan Rosner PRESS FREEDOM FOR THE PEOPLE 3 government officials, investigations of unauthorized disclosures to the press, tighter restrictions on access to the White House and key agencies and officials, lawsuits targeted at crippling or bankrupting news outlets, all combined with increasing economic strain on newsrooms. -

4 Quantifiers and Quantified Arguments 4.1 Quantifiers

4 Quantifiers and Quantified Arguments 4.1 Quantifiers Recall from Chapter 3 the definition of a predicate as an assertion con- taining one or more variables such that, if the variables are replaced by objects from a given Universal set U then we obtain a proposition. Let p(x) be a predicate with one variable. Definition If for all x ∈ U, p(x) is true, we write ∀x : p(x). ∀ is called the universal quantifier. Definition If there exists x ∈ U such that p(x) is true, we write ∃x : p(x). ∃ is called the existential quantifier. Note (1) ∀x : p(x) and ∃x : p(x) are propositions and so, in any given example, we will be able to assign truth-values. (2) The definitions can be applied to predicates with two or more vari- ables. So if p(x, y) has two variables we have, for instance, ∀x, ∃y : p(x, y) if “for all x there exists y for which p(x, y) is holds”. (3) Let A and B be two sets in a Universal set U. Recall the definition of A ⊆ B as “every element of A is in B.” This is a “for all” statement so we should be able to symbolize it. We do so by first rewriting the definition as “for all x ∈ U, if x is in A then x is in B, ” which in symbols is ∀x ∈ U : if (x ∈ A) then (x ∈ B) , or ∀x :(x ∈ A) → (x ∈ B) . 1 (4*) Recall that a variable x in a propositional form p(x) is said to be free. -

Some Common Fallacies of Argument Evading the Issue: You Avoid the Central Point of an Argument, Instead Drawing Attention to a Minor (Or Side) Issue

Some Common Fallacies of Argument Evading the Issue: You avoid the central point of an argument, instead drawing attention to a minor (or side) issue. ex. You've put through a proposal that will cut overall loan benefits for students and drastically raise interest rates, but then you focus on how the system will be set up to process loan applications for students more quickly. Ad hominem: Here you attack a person's character, physical appearance, or personal habits instead of addressing the central issues of an argument. You focus on the person's personality, rather than on his/her ideas, evidence, or arguments. This type of attack sometimes comes in the form of character assassination (especially in politics). You must be sure that character is, in fact, a relevant issue. ex. How can we elect John Smith as the new CEO of our department store when he has been through 4 messy divorces due to his infidelity? Ad populum: This type of argument uses illegitimate emotional appeal, drawing on people's emotions, prejudices, and stereotypes. The emotion evoked here is not supported by sufficient, reliable, and trustworthy sources. Ex. We shouldn't develop our shopping mall here in East Vancouver because there is a rather large immigrant population in the area. There will be too much loitering, shoplifting, crime, and drug use. Complex or Loaded Question: Offers only two options to answer a question that may require a more complex answer. Such questions are worded so that any answer will implicate an opponent. Ex. At what point did you stop cheating on your wife? Setting up a Straw Person: Here you address the weakest point of an opponent's argument, instead of focusing on a main issue.