The Small Museums Cataloguing Manual

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Development of a Dedicated Laser-Polarization Beamline for ISOLDE-CERN

ARENBERG DOCTORAL SCHOOL Faculty of Science Development of a dedicated laser-polarization beamline for ISOLDE-CERN CERN-THESIS-2018-324 //2019 Wouter Gins Supervisor: Dissertation presented in partial Prof. dr. G. Neyens fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Science (PhD): Physics January 2019 Development of a dedicated laser-polarization beamline for ISOLDE-CERN Wouter GINS Examination committee: Dissertation presented in partial Prof. dr. E. Janssens, chair fulfillment of the requirements for Prof. dr. G. Neyens, supervisor the degree of Doctor of Science Prof. dr. N. Severijns (PhD): Physics Prof. dr. R. Raabe Prof. dr. T. E. Cocolios Dr. M. L. Bissell (The University of Manchester) Dr. M. Kowalska (CERN) January 2019 © 2019 KU Leuven – Faculty of Science Uitgegeven in eigen beheer, Wouter Gins, Celestijnenlaan 200D - 2418, B-3001 Leuven (Belgium) Alle rechten voorbehouden. Niets uit deze uitgave mag worden vermenigvuldigd en/of openbaar gemaakt worden door middel van druk, fotokopie, microfilm, elektronisch of op welke andere wijze ook zonder voorafgaande schriftelijke toestemming van de uitgever. All rights reserved. No part of the publication may be reproduced in any form by print, photoprint, microfilm, electronic or any other means without written permission from the publisher. Dankwoord De laatste loodjes wegen het zwaarst, maar als de laatste stap van het schrijven van een thesis het dankwoord is, is de last toch net iets minder groot. Eerst en vooral: Gerda, bedankt voor de begeleiding die reeds tijdens mijn master begon. Door de uitdaging die je mij hebt overtuigd vol te houden ben ik volledig veranderd in de laatste vier jaar, ten goede. -

Historic Costuming Presented by Jill Harrison

Historic Southern Indiana Interpretation Workshop, March 2-4, 1998 Historic Costuming Presented By Jill Harrison IMPRESSIONS Each of us makes an impression before ever saying a word. We size up visitors all the time, anticipating behavior from their age, clothing, and demeanor. What do they think of interpreters, disguised as we are in the threads of another time? While stressing the importance of historically accurate costuming (outfits) and accoutrements for first- person interpreters, there are many reasons compromises are made - perhaps a tight budget or lack of skilled construction personnel. Items such as shoes and eyeglasses are usually a sticking point when assembling a truly accurate outfit. It has been suggested that when visitors spot inaccurate details, interpreter credibility is downgraded and visitors launch into a frame of mind to find other inaccuracies. This may be true of visitors who are historical reenactors, buffs, or other interpreters. Most visitors, though, lack the heightened awareness to recognize the difference between authentic period detailing and the less-than-perfect substitutions. But everyone will notice a wristwatch, sunglasses, or tennis shoes. We have a responsibility to the public not to misrepresent the past; otherwise we are not preserving history but instead creating our own fiction and calling it the truth. Realistically, the appearance of the interpreter, our information base, our techniques, and our environment all affect the first-person experience. Historically accurate costuming perfection is laudable and reinforces academic credence. The minute details can be a springboard to important educational concepts; but the outfit is not the linchpin on which successful interpretation hangs. -

Buxus Sempervirens1

Fact Sheet FPS-80 October, 1999 Buxus sempervirens1 Edward F. Gilman2 Introduction Long a tradition in colonial landscapes, Boxwood is a fine- textured plant familiar to most gardeners and non-gardeners alike (Fig. 1). Eventually reaching 6- to 8-feet-tall (old specimens cab be much taller), Boxwood grows slowly into a billowing mound of soft foliage. Flowers are borne in the leaf axils and are barely noticeable to the eye, but they have a distinctive aroma that irritates some people. General Information Scientific name: Buxus sempervirens Pronunciation: BUCK-sus sem-pur-VYE-renz Common name(s): Common Boxwood, Common Box, American Boxwood Family: Buxaceae Plant type: shrub USDA hardiness zones: 6 through 8 (Fig. 2) Planting month for zone 7: year round Planting month for zone 8: year round Origin: not native to North America Figure 1. Common Boxwood. Uses: border; edging; foundation; superior hedge Availablity: generally available in many areas within its Growth rate: slow hardiness range Texture: fine Description Foliage Height: 8 to 20 feet Spread: 10 to 15 feet Leaf arrangement: opposite/subopposite Plant habit: round Leaf type: simple Plant density: dense Leaf margin: entire 1.This document is Fact Sheet FPS-80, one of a series of the Environmental Horticulture Department, Florida Cooperative Extension Service, Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences, University of Florida. Publication date: October, 1999 Please visit the EDIS Web site at http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu. 2.Edward F. Gilman, professor, Environmental Horticulture Department, Cooperative Extension Service, Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences, University of Florida, Gainesville, 32611. The Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences is an equal opportunity/affirmative action employer authorized to provide research, educational information and other services only to individuals and institutions that function without regard to race, color, sex, age, handicap, or national origin. -

Open As a Single Document

·arno ~a Volume G 1· Number 4· 2002 Page 2 Gestalt Dendrology: Looking at the Arnoldia (ISSN 004-2633; USPS 866-100) is Whole Tree published quarterly by the Arnold Arboretum of Peter Del Tredici Harvard University. Second-class postage paid at Boston, Massachusetts. 9 John Adams, Farmer and Gardener Corhss Knapp Engle Subscriptions are $20.00 per calendar year domestic, $25.00 foreign, payable m advance. Single copies of 15 The Discovery and Rediscovery of the most issues are $5.00; the exceptions are 58/4-59/1 Horse Chestnut (Metasequoza After Fifty Years) and 54/4 (A Source- H. Walter Lack book of Culuvar Names), which are $10.00. Remit- tances may be made m U.S. dollars, by check drawn 20 The Handsome (and Useful) Horse on a U.S. bank; by international money order; or Chestnut by Visa or Mastercard. Send orders, remittances, Klaus K. Loenhart change-of-address notices, and all other subscription- related commumcations to: Circulation Manager, 23 The Horse Chestnut: Accolades from Arnoldia, The Arnold Arboretum, 125 Arborway, Charles S. Sargent Jamaica Plain, Massachusetts 02130-3500. Telephone 617/524-1718; facsimile 617/524-1418; 25 Index to Volume 61 e-mail [email protected]. Front cover A species of Cecropia growing m Postmaster: Send address changes to Equador’s Amazon Basm, clearly showmg the tree’s Arnoldia Circulation Manager modular construction. As trees age, the modules that The Arnold Arboretum define their architecture repeat themselves, becoming 125 Arborway smaller and more numerous. All cover photographs Jamaica Plain, MA 02130-3500 by Peter Del Tredici Inside front cover The trunk of a bnstlecone pme, Karen Editor Madsen, Pmus anstata, growing on Mt. -

NAUMKEAG Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 NAUMKEAG Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 1. NAME OF PROPERTY Historic Name: Naumkeag Other Name/Site Number: N/A 2. LOCATION Street & Number: 5 Prospect Hill Road Not for publication: City/Town: Stockbridge Vicinity: State: MA County: Berkshire Code: 003 Zip Code: 01262 3. CLASSIFICATION Ownership of Property Category of Property Private: X Building(s): ___ Public-Local: District: _X_ Public-State: ___ Site: ___ Public-Federal: ___ Structure: ___ Object: ___ Number of Resources within Property Contributing Noncontributing 10 buildings 11 sites 2 structures objects 23 Total Number of Contributing Resources Previously Listed in the National Register: 1 Name of Related Multiple Property Listing: NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 NAUMKEAG Page 2 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 4. STATE/FEDERAL AGENCY CERTIFICATION As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this ____ nomination ____ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property ____ meets ____ does not meet the National Register Criteria. Signature of Certifying Official Date State or Federal Agency and Bureau In my opinion, the property ____ meets ____ does not meet the National Register criteria. -

Verticillium Wilt of Trees and Shrubs

Dr. Sharon M. Douglas Department of Plant Pathology and Ecology The Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station 123 Huntington Street, P. O. Box 1106 New Haven, CT 06504 Phone: (203) 974-8601 Fax: (203) 974-8502 Founded in 1875 Email: [email protected] Putting science to work for society Website: www.ct.gov/caes VERTICILLIUM WILT OF ORNAMENTAL TREES AND SHRUBS Verticillium wilt is a common disease of a wide variety of ornamental trees and shrubs throughout the United States and Connecticut. Maple, smoke-tree, elm, redbud, viburnum, and lilac are among the more important hosts of this disease. Japanese maples appear to be particularly susceptible and often collapse shortly after the disease is detected. Plants weakened by root damage from drought, waterlogged soils, de-icing salts, and other environmental stresses are thought to be more prone to infection. Figure 1. Japanese maple with acute symptoms of Verticillium wilt. Verticillium wilt is caused by two closely related soilborne fungi, Verticillium dahliae They also develop a variety of symptoms and V. albo-atrum. Isolates of these fungi that include wilting, curling, browning, and vary in host range, pathogenicity, and drying of leaves. These leaves usually do virulence. Verticillium species are found not drop from the plant. In other cases, worldwide in cultivated soils. The most leaves develop a scorched appearance, show common species associated with early fall coloration, and drop prematurely Verticillium wilt of woody ornamentals in (Figure 2). Connecticut is V. dahliae. Plants with acute infections start with SYMPTOMS AND DISEASE symptoms on individual branches or in one DEVELOPMENT: portion of the canopy. -

Conservation of Coated and Specialty Papers

RELACT HISTORY, TECHNOLOGY, AND TREATMENT OF SPECIALTY PAPERS FOUND IN ARCHIVES, LIBRARIES AND MUSEUMS: TRACING AND PIGMENT-COATED PAPERS By Dianne van der Reyden (Revised from the following publications: Pigment-coated papers I & II: history and technology / van der Reyden, Dianne; Mosier, Erika; Baker, Mary , In: Triennial meeting (10th), Washington, DC, 22-27 August 1993: preprints / Paris: ICOM , 1993, and Effects of aging and solvent treatments on some properties of contemporary tracing papers / van der Reyden, Dianne; Hofmann, Christa; Baker, Mary, In: Journal of the American Institute for Conservation, 1993) ABSTRACT Museums, libraries, and archives contain large collections of pigment-coated and tracing papers. These papers are produced by specially formulated compositions and manufacturing procedures that make them particularly vulnerable to damage as well as reactive to solvents used in conservation treatments. In order to evaluate the effects of solvents on such papers, several research projects were designed to consider the variables of paper composition, properties, and aging, as well as type of solvent and technique of solvent application. This paper summarizes findings for materials characterization, degradative effects of aging, and some effects of solvents used for stain reduction, and humidification and flattening, of pigment-coated and modern tracing papers. Pigment-coated papers have been used, virtually since the beginning of papermaking history, for their special properties of gloss and brightness. These properties, however, may render coated papers more susceptible to certain types of damage (surface marring, embedded grime, and stains) and more reactive to certain conservation treatments. Several research projects have been undertaken to characterize paper coating compositions (by SEM/EDS and FTIR) and appearance properties (by SEM imaging of surface structure and quantitative measurements of color and gloss) in order to evaluate changes that might occur following application of solvents used in conservation treatments. -

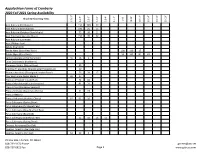

Appalachian Farms of Cranberry 2020 Fall 2021 Spring Availability

Appalachian Farms of Cranberry 2020 Fall 2021 Spring Availability Shade & Flowering Trees 6-8' 8-10' 2-2.5" 2.5-3" 3-3.5" 3.5-4" 4-4.5" 10-12' 12-14' 14-16' 16-18' 1.75-2" Acer Rubrum (Red Sunset) 150 100 30 Acer Rubrum (Brandywine) 100 25 15 Acer Rubrum (October Glory Maple) 75 30 11 Acer Freemanii (Autumn Blaze) 150 70 32 Acer Rubrum (Somerset) Acer ( Ribbon Leaf) Betula River Birch Betula Nigra (Dura Heat Birch) 100 130 17 Betula Nigra (River Birch) 50 143 81 43 Cercis Canadensis (The Rising Sun) 40 16 2 Celtis Occidentalis (Hackberry) Crataegus Viridis (Winter King) 59 Gleditsia Triacanthos (Shademaster Honeylocust) 30 Platanus Acerifolia (Bloodgood London Plane) 76 39 17 Acer Saccharum (Sugar Maple ) 40 27 Prunus x (Thunder Cloud) Plum 71 16 Prunus Myroboian (Krauter Vesuvius) 81 31 Prunus Plum (Kankakee Newport) Prunus Serrulata (Kwanzana Cherry) 51 19 Prunus Akebono Prunus Yedoensis (Yoshino Cherry) 10 61 16 Pyrus Calleryana (Spring Show) Pyrus Calleryana (Aristocrat Pear) Pyrus Calleryana (New Bradford Pear) Pyrus Calleryana (Bradford) Pyrus Calleryana (Cleveland Pear) 52 18 16 52 Pyrus Calleryana (Spring Show) Quercus Acutissima (Bur Oak) Quercus Palustris (Heritage Oak) Quercus Palustris (Pin Oak) 62 39 3 PO Box 686, Elk Park, NC 28622 828-733-3174 Phone [email protected] 828-737-6922 Fax Page 1 www.gstrees.com Appalachian Farms of Cranberry 2020 Fall 2021 Spring Availability Shade & Flowering Trees cont. 6-8' 8-10' 2-2.5" 2.5-3" 3-3.5" 3.5-4" 4-4.5" 10-12' 12-14' 14-16' 16-18' 1.75-2" Quercus Rubra (Red Oak) 33 57 27 2 Quercus -

Annual Review Are Intended Director on His fi Rst Visit to the Gallery

THE April – March NATIONAL GALLEY TH E NATIONAL GALLEY April – March – Contents Introduction 5 In June , Dr Nicholas Penny announced During Nicholas Penny’s directorship, overall Director’s Foreword 8 his intention to retire as Director of the National visitor numbers have grown steadily, year on year; Gallery. The handover to his successor, Dr Gabriele in , they stood at some . million while in Acquisitions 10 Finaldi, will take place in August . The Board they reached over . million. Furthermore, Loans 17 looks forward to welcoming Dr Finaldi back to this remarkable increase has taken place during a Conservation 24 the Gallery, where he worked as a curator from period when our resource Grant in Aid has been Framing 28 to . falling. One of the key objectives of the Gallery Exhibitions 32 This, however, is the moment at which to over the last few years has been to improve the Displays 44 refl ect on the directorship of Nicholas Penny, experience for this growing group of visitors, Education 48 the eminent scholar who has led the Gallery so and to engage them more closely with the Scientifi c Research 52 successfully since February . As Director, Gallery and its collection. This year saw both Research and Publications 55 his fi rst priority has been the security, preservation the introduction of Wi-Fi and the relaxation Public and Private Support of the Gallery 60 and enhanced display of the Gallery’s pre-eminent of restrictions on photography, changes which Trustees and Committees of the National Gallery Board 66 collection of Old Master paintings for the benefi t of have been widely welcomed by our visitors. -

French and Hessian Impressions: Foreign Soldiers' Views of America During the Revolution

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2003 French and Hessian Impressions: Foreign Soldiers' Views of America during the Revolution Cosby Williams Hall College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the Military History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Hall, Cosby Williams, "French and Hessian Impressions: Foreign Soldiers' Views of America during the Revolution" (2003). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539626414. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-a7k2-6k04 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FRENCH AND HESSIAN IMPRESSIONS: FOREIGN SOLDIERS’ VIEWS OF AMERICA DURING THE REVOLUTION A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Cosby Hall 2003 a p p r o v a l s h e e t This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts CosbyHall Approved, September 2003 _____________AicUM James Axtell i Ronald Hoffman^ •h im m > Ronald S chechter TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Acknowledgements iv Abstract V Introduction 2 Chapter 1: Hessian Impressions 4 Chapter 2: French Sentiments 41 Conclusion 113 Bibliography 116 Vita 121 iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The writer wishes to express his sincere appreciation to Professor James Axtell, under whose guidance this paper was written, for his advice, editing, and wisdom during this project. -

Green Valley Farms, Inc

Green Valley Farms, Inc. 7/22/2021 Pre-dug B & B Size Available Acer buergerianum, Trident Maple 2" 20 Acer buergerianum, Trident Maple 2.5" 4 Acer buergerianum, Trident Maple 3" 0 Acer buergerianum, Trident Maple 3.5" 0 Acer dissectum 'Tamukeyama' 3-4' 9 Acer dissectum 'Virdis' 3-4' 4 Acer palmatum 'Bloodgood' Japanese Maple 4-5' 0 Acer palmatum 'Bloodgood' Japanese Maple 5-6' 14 Acer palmatum 'Bloodgood' Japanese Maple 6-7' 8 Acer palmatum 'Bloodgood' Japanese Maple 7-8' 0 Acer palmatum 'Bloodgood' Japanese Maple 8' Heavy 0 Acer palmatum 'Bloodgood' Japanese Maple 10' 0 Acer palmatum, Green Leaf multi trunk 5-6' 0 Acer palmatum, Green Leaf multi trunk 6-7' 2 Acer palmatum, Green Leaf multi trunk 7' 0 Acer palmatum, Green Leaf multi trunk 8-9' 0 Acer palmatum 'Sango Kaku' 6-7' 0 Acer palmatum 'Sango Kaku' clump 5-6' 0 Acer palmatum 'Tobiosho' 6-7' 0 Acer palmatum 'Tobiosho' 7-8' 0 Acer rubrum 'October Glory' 2" 0 Acer rubrum 'October Glory' 2.5" 3 Acer rubrum 'October Glory' 3" 26 Acer rubrum 'Summer Red' 2" 0 Acer rubrum 'Summer Red' 2.5" 32 Acer saccharum 'Bailsta' Fall Festival 2" 0 Acer saccharum 'Legacy' Sugar Maple 2" 25 Acer saccharum 'Legacy' Sugar Maple 2.5" 0 Commeration sugar maple 2" 0 Amelanchier grandiflora 'Autumn Brilliance' 6-8' 0 Amelanchier grandiflora 'Autumn Brilliance' 8-10' 0 Amelanchier grandiflora 'Autumn Brilliance' 10-12' 0 Betula nigra 'BNMTF' Duraheat River Birch 6-8' 0 Betula nigra 'BNMTF' Duraheat River Birch 8-10' 2 Betula nigra 'BNMTF' Duraheat River Birch 10-12' 45 Betula nigra 'BNMTF' Duraheat River Birch 12-14' 29 Betula nigra 'BNMTF' Duraheat River Birch 14-16' 0 Betula nigra 'BNMTF' Duraheat River Birch 2.5" STD. -

Buxus Sempervirens (Common Boxwood) Size/Shape

Buxus sempervirens (Common Boxwood) Boxwood has traditional landscape use, just think of old English or French gardens. Eventually reaching 1-1.5 m (back in nature its able to reach 5-8 m). Boxwood grows very slowly. It has a small evergreen ovate leaves where the venation does show at all. The leaves are about 1 cm. The flowers are born in the leaf axis but unnoticeable for the eye. Use this plant as a hedge, mass planting and the best for topiary. It needs partial sun or shade. It grows best on clay or loamy soil. On sand it requires continues irrigation plus on sand several nematodes gives trouble for the plant. Landscape Information French Name: Buis Pronounciation: BUCK-sus sem-pur-VYE-renz Plant Type: Shrub Origin: Southern Europe, Northen Africa Heat Zones: 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 Hardiness Zones: 6, 7, 8 Uses: Hedge, Topiary, Specimen, Container Size/Shape Growth Rate: Slow Tree Shape: Round Canopy Symmetry: Symmetrical Canopy Density: Dense Plant Image Canopy Texture: Coarse Height at Maturity: 1.5 to 3 m Spread at Maturity: 1.5 to 3 meters Time to Ultimate Height: 20 to 50 Years Buxus sempervirens (Common Boxwood) Botanical Description Foliage Leaf Arrangement: Opposite Leaf Venation: Pinnate Leaf Persistance: Evergreen Leaf Type: Simple Leaf Blade: Less than 5 Leaf Shape: Oval Leaf Margins: Entire Leaf Textures: Glossy, Coarse Leaf Scent: No Fragance Color(growing season): Green Color(changing season): Green Flower Flower Showiness: False Flower Image Flower Size Range: 1.5 - 3 Flower Type: Capitulum Flower Sexuality: Monoecious (Bisexual)