Open As a Single Document

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Buxus Sempervirens1

Fact Sheet FPS-80 October, 1999 Buxus sempervirens1 Edward F. Gilman2 Introduction Long a tradition in colonial landscapes, Boxwood is a fine- textured plant familiar to most gardeners and non-gardeners alike (Fig. 1). Eventually reaching 6- to 8-feet-tall (old specimens cab be much taller), Boxwood grows slowly into a billowing mound of soft foliage. Flowers are borne in the leaf axils and are barely noticeable to the eye, but they have a distinctive aroma that irritates some people. General Information Scientific name: Buxus sempervirens Pronunciation: BUCK-sus sem-pur-VYE-renz Common name(s): Common Boxwood, Common Box, American Boxwood Family: Buxaceae Plant type: shrub USDA hardiness zones: 6 through 8 (Fig. 2) Planting month for zone 7: year round Planting month for zone 8: year round Origin: not native to North America Figure 1. Common Boxwood. Uses: border; edging; foundation; superior hedge Availablity: generally available in many areas within its Growth rate: slow hardiness range Texture: fine Description Foliage Height: 8 to 20 feet Spread: 10 to 15 feet Leaf arrangement: opposite/subopposite Plant habit: round Leaf type: simple Plant density: dense Leaf margin: entire 1.This document is Fact Sheet FPS-80, one of a series of the Environmental Horticulture Department, Florida Cooperative Extension Service, Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences, University of Florida. Publication date: October, 1999 Please visit the EDIS Web site at http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu. 2.Edward F. Gilman, professor, Environmental Horticulture Department, Cooperative Extension Service, Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences, University of Florida, Gainesville, 32611. The Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences is an equal opportunity/affirmative action employer authorized to provide research, educational information and other services only to individuals and institutions that function without regard to race, color, sex, age, handicap, or national origin. -

NAUMKEAG Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 NAUMKEAG Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 1. NAME OF PROPERTY Historic Name: Naumkeag Other Name/Site Number: N/A 2. LOCATION Street & Number: 5 Prospect Hill Road Not for publication: City/Town: Stockbridge Vicinity: State: MA County: Berkshire Code: 003 Zip Code: 01262 3. CLASSIFICATION Ownership of Property Category of Property Private: X Building(s): ___ Public-Local: District: _X_ Public-State: ___ Site: ___ Public-Federal: ___ Structure: ___ Object: ___ Number of Resources within Property Contributing Noncontributing 10 buildings 11 sites 2 structures objects 23 Total Number of Contributing Resources Previously Listed in the National Register: 1 Name of Related Multiple Property Listing: NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 NAUMKEAG Page 2 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 4. STATE/FEDERAL AGENCY CERTIFICATION As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this ____ nomination ____ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property ____ meets ____ does not meet the National Register Criteria. Signature of Certifying Official Date State or Federal Agency and Bureau In my opinion, the property ____ meets ____ does not meet the National Register criteria. -

Verticillium Wilt of Trees and Shrubs

Dr. Sharon M. Douglas Department of Plant Pathology and Ecology The Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station 123 Huntington Street, P. O. Box 1106 New Haven, CT 06504 Phone: (203) 974-8601 Fax: (203) 974-8502 Founded in 1875 Email: [email protected] Putting science to work for society Website: www.ct.gov/caes VERTICILLIUM WILT OF ORNAMENTAL TREES AND SHRUBS Verticillium wilt is a common disease of a wide variety of ornamental trees and shrubs throughout the United States and Connecticut. Maple, smoke-tree, elm, redbud, viburnum, and lilac are among the more important hosts of this disease. Japanese maples appear to be particularly susceptible and often collapse shortly after the disease is detected. Plants weakened by root damage from drought, waterlogged soils, de-icing salts, and other environmental stresses are thought to be more prone to infection. Figure 1. Japanese maple with acute symptoms of Verticillium wilt. Verticillium wilt is caused by two closely related soilborne fungi, Verticillium dahliae They also develop a variety of symptoms and V. albo-atrum. Isolates of these fungi that include wilting, curling, browning, and vary in host range, pathogenicity, and drying of leaves. These leaves usually do virulence. Verticillium species are found not drop from the plant. In other cases, worldwide in cultivated soils. The most leaves develop a scorched appearance, show common species associated with early fall coloration, and drop prematurely Verticillium wilt of woody ornamentals in (Figure 2). Connecticut is V. dahliae. Plants with acute infections start with SYMPTOMS AND DISEASE symptoms on individual branches or in one DEVELOPMENT: portion of the canopy. -

Appalachian Farms of Cranberry 2020 Fall 2021 Spring Availability

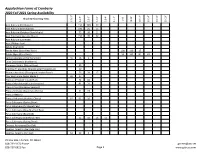

Appalachian Farms of Cranberry 2020 Fall 2021 Spring Availability Shade & Flowering Trees 6-8' 8-10' 2-2.5" 2.5-3" 3-3.5" 3.5-4" 4-4.5" 10-12' 12-14' 14-16' 16-18' 1.75-2" Acer Rubrum (Red Sunset) 150 100 30 Acer Rubrum (Brandywine) 100 25 15 Acer Rubrum (October Glory Maple) 75 30 11 Acer Freemanii (Autumn Blaze) 150 70 32 Acer Rubrum (Somerset) Acer ( Ribbon Leaf) Betula River Birch Betula Nigra (Dura Heat Birch) 100 130 17 Betula Nigra (River Birch) 50 143 81 43 Cercis Canadensis (The Rising Sun) 40 16 2 Celtis Occidentalis (Hackberry) Crataegus Viridis (Winter King) 59 Gleditsia Triacanthos (Shademaster Honeylocust) 30 Platanus Acerifolia (Bloodgood London Plane) 76 39 17 Acer Saccharum (Sugar Maple ) 40 27 Prunus x (Thunder Cloud) Plum 71 16 Prunus Myroboian (Krauter Vesuvius) 81 31 Prunus Plum (Kankakee Newport) Prunus Serrulata (Kwanzana Cherry) 51 19 Prunus Akebono Prunus Yedoensis (Yoshino Cherry) 10 61 16 Pyrus Calleryana (Spring Show) Pyrus Calleryana (Aristocrat Pear) Pyrus Calleryana (New Bradford Pear) Pyrus Calleryana (Bradford) Pyrus Calleryana (Cleveland Pear) 52 18 16 52 Pyrus Calleryana (Spring Show) Quercus Acutissima (Bur Oak) Quercus Palustris (Heritage Oak) Quercus Palustris (Pin Oak) 62 39 3 PO Box 686, Elk Park, NC 28622 828-733-3174 Phone [email protected] 828-737-6922 Fax Page 1 www.gstrees.com Appalachian Farms of Cranberry 2020 Fall 2021 Spring Availability Shade & Flowering Trees cont. 6-8' 8-10' 2-2.5" 2.5-3" 3-3.5" 3.5-4" 4-4.5" 10-12' 12-14' 14-16' 16-18' 1.75-2" Quercus Rubra (Red Oak) 33 57 27 2 Quercus -

Green Valley Farms, Inc

Green Valley Farms, Inc. 7/22/2021 Pre-dug B & B Size Available Acer buergerianum, Trident Maple 2" 20 Acer buergerianum, Trident Maple 2.5" 4 Acer buergerianum, Trident Maple 3" 0 Acer buergerianum, Trident Maple 3.5" 0 Acer dissectum 'Tamukeyama' 3-4' 9 Acer dissectum 'Virdis' 3-4' 4 Acer palmatum 'Bloodgood' Japanese Maple 4-5' 0 Acer palmatum 'Bloodgood' Japanese Maple 5-6' 14 Acer palmatum 'Bloodgood' Japanese Maple 6-7' 8 Acer palmatum 'Bloodgood' Japanese Maple 7-8' 0 Acer palmatum 'Bloodgood' Japanese Maple 8' Heavy 0 Acer palmatum 'Bloodgood' Japanese Maple 10' 0 Acer palmatum, Green Leaf multi trunk 5-6' 0 Acer palmatum, Green Leaf multi trunk 6-7' 2 Acer palmatum, Green Leaf multi trunk 7' 0 Acer palmatum, Green Leaf multi trunk 8-9' 0 Acer palmatum 'Sango Kaku' 6-7' 0 Acer palmatum 'Sango Kaku' clump 5-6' 0 Acer palmatum 'Tobiosho' 6-7' 0 Acer palmatum 'Tobiosho' 7-8' 0 Acer rubrum 'October Glory' 2" 0 Acer rubrum 'October Glory' 2.5" 3 Acer rubrum 'October Glory' 3" 26 Acer rubrum 'Summer Red' 2" 0 Acer rubrum 'Summer Red' 2.5" 32 Acer saccharum 'Bailsta' Fall Festival 2" 0 Acer saccharum 'Legacy' Sugar Maple 2" 25 Acer saccharum 'Legacy' Sugar Maple 2.5" 0 Commeration sugar maple 2" 0 Amelanchier grandiflora 'Autumn Brilliance' 6-8' 0 Amelanchier grandiflora 'Autumn Brilliance' 8-10' 0 Amelanchier grandiflora 'Autumn Brilliance' 10-12' 0 Betula nigra 'BNMTF' Duraheat River Birch 6-8' 0 Betula nigra 'BNMTF' Duraheat River Birch 8-10' 2 Betula nigra 'BNMTF' Duraheat River Birch 10-12' 45 Betula nigra 'BNMTF' Duraheat River Birch 12-14' 29 Betula nigra 'BNMTF' Duraheat River Birch 14-16' 0 Betula nigra 'BNMTF' Duraheat River Birch 2.5" STD. -

Buxus Sempervirens (Common Boxwood) Size/Shape

Buxus sempervirens (Common Boxwood) Boxwood has traditional landscape use, just think of old English or French gardens. Eventually reaching 1-1.5 m (back in nature its able to reach 5-8 m). Boxwood grows very slowly. It has a small evergreen ovate leaves where the venation does show at all. The leaves are about 1 cm. The flowers are born in the leaf axis but unnoticeable for the eye. Use this plant as a hedge, mass planting and the best for topiary. It needs partial sun or shade. It grows best on clay or loamy soil. On sand it requires continues irrigation plus on sand several nematodes gives trouble for the plant. Landscape Information French Name: Buis Pronounciation: BUCK-sus sem-pur-VYE-renz Plant Type: Shrub Origin: Southern Europe, Northen Africa Heat Zones: 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9 Hardiness Zones: 6, 7, 8 Uses: Hedge, Topiary, Specimen, Container Size/Shape Growth Rate: Slow Tree Shape: Round Canopy Symmetry: Symmetrical Canopy Density: Dense Plant Image Canopy Texture: Coarse Height at Maturity: 1.5 to 3 m Spread at Maturity: 1.5 to 3 meters Time to Ultimate Height: 20 to 50 Years Buxus sempervirens (Common Boxwood) Botanical Description Foliage Leaf Arrangement: Opposite Leaf Venation: Pinnate Leaf Persistance: Evergreen Leaf Type: Simple Leaf Blade: Less than 5 Leaf Shape: Oval Leaf Margins: Entire Leaf Textures: Glossy, Coarse Leaf Scent: No Fragance Color(growing season): Green Color(changing season): Green Flower Flower Showiness: False Flower Image Flower Size Range: 1.5 - 3 Flower Type: Capitulum Flower Sexuality: Monoecious (Bisexual) -

A Guide to Lesser Known Tropical Timber Species July 2013 Annual Repo Rt 2012 1 Wwf/Gftn Guide to Lesser Known Tropical Timber Species

A GUIDE TO LESSER KNOWN TROPICAL TIMBER SPECIES JULY 2013 ANNUAL REPO RT 2012 1 WWF/GFTN GUIDE TO LESSER KNOWN TROPICAL TIMBER SPECIES BACKGROUND: BACKGROUND: The heavy exploitation of a few commercially valuable timber species such as Harvesting and sourcing a wider portfolio of species, including LKTS would help Mahogany (Swietenia spp.), Afrormosia (Pericopsis elata), Ramin (Gonostylus relieve pressure on the traditionally harvested and heavily exploited species. spp.), Meranti (Shorea spp.) and Rosewood (Dalbergia spp.), due in major part The use of LKTS, in combination with both FSC certification, and access to high to the insatiable demand from consumer markets, has meant that many species value export markets, could help make sustainable forest management a more are now threatened with extinction. This has led to many of the tropical forests viable alternative in many of WWF’s priority places. being plundered for these highly prized species. Even in forests where there are good levels of forest management, there is a risk of a shift in species composition Markets are hard to change, as buyers from consumer countries often aren’t in natural forest stands. This over-exploitation can also dissuade many forest willing to switch from purchasing the traditional species which they know do managers from obtaining Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) certification for the job for the products that they are used in, and for which there is already their concessions, as many of these high value species are rarely available in a healthy market. To enable the market for LKTS, there is an urgent need to sufficient quantity to cover all of the associated costs of certification. -

Heritage Gardens

HERITAGE GARDENS: AREA B WALK TO PERGOLA AREA C HOSTAS AREA J NORTH SIDE PERGOLA STONE BOTH SIDES BUILDING OF WALL LAWN AREA I NORTHWEST WALKWAY AREA D NORTHEAST SIDE OF AREA H HOUSE PATIO TIERS AREA A EASTERN PARKING LOT Fire Hydrant AREA E FRONT LAWN SWEEP PAVILION AREA G TOP OF HILL & HILLSIDE AREA F SOUTH OUTSIDE FENCE Date: 03/04/2021 Sheet Title: COVER Sheet No: 0 5 10 20 40 CS HERITAGE GARDENS Eller Park - Fishers, Indiana 10 LEGEND -Building - Lawn - Side walk 9 - Brick walk - Asphalt 6 5 - Sculptures 6 9 4 4 9 - Plants 1 2 7 2 8 3 AREA J NORTH SIDE AREA C AREA B BOTH SIDES OF WALL HOSTAS WALK TO PERGOLA STONE BUILDING LAWN AREA I NORTHWEST AREA WALKWAY AREA D A AMBASSADOR NORTHEAST EASTERN HOUSE SIDE OF PARKING AREA H HOUSE LOT PATIO TIERS AREA E FRONT LAWN PAVILION SWEEP AREA G TOP OF HILL & HILLSIDE AREA F SOUTH AREA A EASTERN PARKING LOT OUTSIDE KEY PLAN FENCE Tag Common Name Scientific Name Flowers 1 2 3 4 5 A1 Spirea Spiraea Shirobana Pinkish summer A2 Dogwood 'Ivory Halo' Cornus Alba No flowers A3 Magnolia 'Ann' Pinkish red in spring A4 Quince 'Orange Storm' Chaenomeles Orange Speciosa 6 7 8 9 10 A5 Eastern Hemlock Tsuga Canadensis Small cones A6 Viburnum 'Chicago Viburnum Dentatum White, blue fruit turns Lustre' blk A7 Horse Chestnut Tree Aesculus Pinkish in May, showy Hippocastanum A8 Common Lilac Syringa White? A9 Stella de Oro Daylily Hemeorcallis Yellow in summer A10 Lambs Ear Stachys Byzantina Pinkish HERITAGE GARDENS Eller Park - Fishers, Indiana Sheet Title: ANNO-A Sheet No: A-101a HERITAGE GARDENS Eller Park - -

Boxwood Varieties Resistant to Boxwood Blight

RESEARCH LABORATORY TECHNICAL REPORT Boxwoods Resistant to Boxwood Blight By The Bartlett Lab Staff Directed by Kelby Fite, PhD Research that evaluated resistance of boxwood species and varieties to boxwood blight indicates that resistance is largely related to geographic origin of the plant. Asian species generally exhibit greatest resistances while European species show the greatest susceptibility. Hybrids between Asian and European plants exhibit intermediate resistance. Form and size also appears to have some influence on blight susceptibility. Boxwood selections with compact forms that exhibit slow growth are generally more susceptible than cultivars that have an open and larger form. The following boxwood species and cultivars exhibited the highest level of resistance in research conducted by North Carolina State University. Unless noted, these selections are suitable in hardiness zones 6 through 8. Buxus microphylla var. japonica ‘Green Beauty’ Buxus sinica var.insularis ‘Nana’ Green Beauty Boxwood Dwarf Korean Boxwood A large maturing species, this Japanese boxwood This cultivar is a dwarf, slow growing selection with a selection attains a height of six–to-eight feet after 15 mounded form that is suitable as an edging boxwood. years in the landscape. The plant has a mounded, loose Attains a height of two feet with a potentially wider open form. Susceptible to boxwood leafminer. spread after 15 years. It is resistant to boxwood Remains green through winter. leafminer. Exhibits foliage yellowing in winter. Page 1 of 4 Buxus microphylla ‘Golden Dream’ Buxus ‘Green Gem’ Golden Dream Littleleaf Boxwood Green Gem Boxwood This cultivar has leaves with gold variegation. The A hybrid between B. -

Reproductive Ecology of Two Pioneer Legumes in a Coastal Plain Degraded by Sand Mining1

Hoehnea 45(1): 93-102, 2 tab., 2 fi g., 2018 http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/2236-8906-53/2017 Reproductive ecology of two pioneer legumes in a coastal plain degraded by sand mining1 Adriana de Oliveira Fidalgo 2,3, Débora Marcouizos Guimarães2, Gabriela Toledo Caldiron2 and José Marcos Barbosa2 Received: 22.08.2017; accepted: 19.12.2017 ABSTRACT - (Reproductive ecology of two pioneer legumes in a coastal plain degraded by sand mining). The present study evaluates and compares the phenology, pollination biology and breeding systems of Chamaecrista desvauxii (Collad.) Killip. and Clitoria laurifolia Poir. in a coastal plain degraded by sand mining in São Paulo State, Brazil, from January 2006 to May 2008. Flowering and fruiting events occurred in the warm and rainy season. Both species are self-compatible but only C. desvauxii was pollinator-dependent to set fruits. A small group of bees, comprising Eufrisea sp., Eulaema (Apeulaema) cingulata and Bombus morio, accessed the male and female fl oral structures and moved among individuals resulting in cross- pollinations. However, only B. morio was a frequent visitor and an effective pollinator. Although recruitment and survival of population in the study area are high for both species, we observed lower abundance and richness of visitors suggesting the possible lack of pollinators and pollen limitation. Keywords: Bee pollination, Bombus, Fabaceae, disturbed areas, pollen limitation RESUMO - (Ecologia reprodutiva de duas leguminosas pioneiras em planície costeira degradada por mineração). O presente estudo avaliou e comparou a fenologia, a biologia da polinização e os sistemas de reprodução de Chamaecrista desvauxii (Collad.) Killip.and Clitoria laurifolia Poir. -

Evergreen Shrubs Fact Sheet No

Evergreen Shrubs Fact Sheet No. 7.414 Gardening Series|Trees and Shrubs by J.E. Klett and R.A. Cox* Evergreens add year-round beauty and Drainage and Soil Conditions Quick Facts attractiveness to home landscapes. For Good drainage and soil aeration are • All evergreens lose some of practical purposes, evergreen shrubs are essential for optimum growth. Where classified as broadleaved or narrowleaved. planting soils are mostly clay, amend them their leaves each year. Narrowleaved evergreens such as pines and with coarse organic material such as compost, • Broadleaved evergreens junipers have needle-like foliage. Evergreen sphagnum peat or aged barnyard manure. plants that do not have needle-like foliage are grow best in areas protected It takes about 3-5 cubic yards of organic from winter sun, cold and known as broadleaved evergreens. material per 1,000 square feet to improve a drying winds. All evergreens lose some of their leaves clay soil. Thoroughly mix the organic material each year. Most broadleaved evergreens lose into clay soil, to a depth of 8 to 10 inches. • When selecting evergreens, some of the older leaves during the winter If planting soils are too sandy, improve consider soil and site or when new growth resumes in the spring. water-holding capacity by similarly adding conditions. Narrowleaved evergreens can maintain organic amendments. An organic mulch foliage for two years or more. Eventually is recommended over the entire area after • Consider mature size when the innermost, oldest foliage drops off. planting. See 7.214, Mulches for Home planting evergreens as Evergreens that are sheared tend to be bare Grounds for more information. -

Availability List 10-5-20

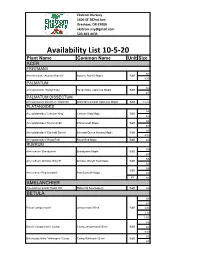

Ekstrom Nursery 1600 SE 282nd Ave. Gresham, OR 97080 [email protected] 503-663-4035 Availability List 10-5-20 Plant Name Common Name Unit Size ACER FREEMANII 6/8 Acer freemanii 'Autumn Blaze®' Autumn Blaze® Maple B&B 8/10 PALMATUM 3/4 Acer palmatum 'Sango Kaku' Sango Kaku Japanese Maple B&B 4/5 PALMATUM DISSECTUM Acer palmatum dissectum 'Waterfall' Waterfall Laceleaf Japanese Maple B&B 18/24 PLATANOIDES 5/6 Acer platanoides 'Crimson King' Crimson King Maple B&B 6/8 5/6 Acer platanoides 'Drummondii' Drummondii Maple B&B 6/8 6/8 Acer platanoides 'Emerald Queen' Emerald Queen Norway Maple B&B 8/10 Acer platanoides 'Royal Red' Royal Red Maple B&B 6/8 RUBRUM 5/6 Acer rubrum 'Brandywine' Brandywine Maple B&B 6/8 5/6 Acer rubrum 'October Glory'® October Glory® Red Maple B&B 6/8 5/6 B&B Acer rubrum Red Sunset® Red Sunset® Maple 6/8 #7 6/8 AMELANCHIER Amelanchier grand. 'Robin Hill' Robin Hill Serviceberry B&B 5/6 BETULA 5/6 6/8 Betula 'Jacquemontii' Jacquemontii Birch B&B 8/10 1.5" 1.75" 5/6 Betula 'Jacquemontii' Clump Clump Jacquemontii Birch B&B 6/8 8/10 5/6 Betula populifolia 'Whitespire' Clump Clump Whitespire Birch B&B 6/8 Plant Name Common Name Unit Size BUXUS 15/18 Buxus hybrid 'Green Mountain' Green Mountain Boxwood B&B 18/24 24/30 Buxus hybrid 'Green Velvet' Green Velvet Boxwood B&B 15/18 15/18 Buxus koreana 'Winter Gem' Winter Gem Boxwood B&B 18/24 24/30 18/24 Buxus sempervirens 'Fastigiata' Upright Boxwood B&B 24/30 30/36 18/24 Buxus sempervirens 'Graham Blandy' Graham Blandy Boxwood B&B 24/30 #2 8/10 Buxus sempervirens 'Suffruticosa' True Dwarf English Boxwood #3 10/12 CEDRUS Cedrus atlantica 'Glauca' Blue Atlas Cedar B&B 4/5 4/5 Cedrus deodara 'Sanders Blue' Sanders Blue Deodara Cedar B&B 5/6 6/7 CERCIS 5/6 Cercis canadensis 'Alba' Alba White Redbud B&B 6/8 5/6 Cercis canadensis 'Eastern Redbud' Eastern Redbud B&B 6/8 8/10 4/5 Cercis canadensis 'Forest Pansy' Forest Pansy Redbud B&B 5/6 6/8 5/6 Cercis canadensis 'Merlot' PP22297 Merlot Redbud B&B 6/8 5/6 Cercis can.