1895, August 9

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cabinet Approves Implementation of 7Th Pay Commission Recommendations

TH 014 YEAR OF PUBLICATIONSRINAGAR | Aprilwww.timeandus.com 25, 2018, Wednesday www.facebook.com/TimeandUs [email protected] timeandus @timeandus WEATHER TEMPERATURE www.timeandus.com www.facebook.com/TimeandUs [email protected] @timeandus STATION MAX TEMPERATURE MIN TEMPERATURE SUNSET WEDNESDAY: 07:10 PM APRIL, 25, 2018 ACT ACT 09 SHABAN 1439 AH SUNRISE THURSDAY: SRINAGAR 26.0 7.1 05:50 AM ISSUE: 97 JAMMU 36.9 18.6 VOLUME: 04 LOCAL FORECAST OF SRINAGAR LEH 17.3 6.5 Mainly Clear Sky. Maximum & Minimum PAGES: 08 KARGIL 17.8 2.4 temperatures will be around 25°C & 08°C respectively. RNI NO: JKENG/2015/62397 PRICE RS.3/- (AIR SURCHARGE FOR DELHI, JAMMU & LADAKH 50/- PAISA) STATE | 3 INTERSTATE | 5 BUSINESS | 7 SPORTS | 8 WOMEN ENTREPRENEURS SHARE THEIR OPEN TO PERMANENT COMMISSION OF INDIA TO IMPORT MORE OIL, DRONES AND RAVICHANDRAN ASHWIN’S BEEN INNOVATIVE AS EXPERIENCES IN INTERNATIONAL SME WOMEN IN ARMY, GOVT TELLS SUPREME AIRCRAFT FROM US AMID TRUMP TRADE WAR KINGS XI PUNJAB CAPTAIN IN IPL 2018 Cabinet approves JK Cabinet approves implementation of Preventive Detention Laws 7th pay commission recommendations Ordinance- 2018 Slew of administrative reforms rolled out Scores transferred, promoted CABINET APPROVES JK Jammu, Apr 24: The state cabinet that met here today Jammu, Apr 24: In a major decision, the under the chairpersonship of Chief Minister Mehbooba state cabinet that met here today under PROTECTION OF CHILDREN Mufti approved the Jammu and Kashmir (Preventive the chairpersonship of Chief Minister Detention laws) Ordinance, 2018. Mehbooba Mufti approved implementa- FROM SEXUAL VIOLENCE According to the decision the Ordinance would provide tion of 7th pay commission recommen- the government a wider choice of retired eligible persons dations for state government employees ORDINANCE-2018 who could be considered for selection/ appointment as and pensioners with effect from January JAMMU, APRIL 24: The state cabinet that met here chairmen and members of the advisory boards under the 2016. -

SRCC) Risks in Engineering Insurance

IMIA Working Group Paper [WGP 90 (15)] IMIA Annual Conference 2015, Merida (Yucatán), Mexico 26-30 September 2015 Strike, Riot and Civil Commotion (SRCC) Risks in Engineering Insurance Fire rages through a building following riots in Tottenham on Aug. 7, 2011 (Lewis Whyld from www.boston.com ) Working Group Members: Chairman: Dieter Spaar, HDI-Gerling Industrie Versicherung AG Contributors: Alon Eisenberg, Engineers, Surveyors & Loss Adjusters Andy Hottinger, AXIS Re Europe Fatih Agacik, VHV AG Federico Pereira, Hannover Re Gerson CMS Raymundo, AXA Corporate Solutions Hari Radhakrishnan, HDFC ERGO General Insurance Co. Ltd. Intigam M. Seyfulla, Azerbaijan Industry Insurance Konstantinos Argyriou, HDI-Gerling Industrie Versicherung AG Matthias Meyer, Munich Re Paul Lowrie, Clyde & Co LLP Stephen Convery, Scor Global P&C IMIA EC Sponsor: Volkan Babür, Mapfre Genel Sigorta IMIA – WGP 90 (15) CONTENT Disclaimer .............................................................................................................................4 Executive Summary .............................................................................................................5 1. Introduction ...................................................................................................................6 2. Legal Aspects & Definitions .........................................................................................8 2.1. SRCC Under English Law ......................................................................................9 2.1.1. Strike -

University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation Formatting Template

A COMPUTATIONAL APPROACH TO CONTEXTUAL INTERNET SEARCH USING MUTUAL INFORMATION WITH LEXICO-SYNTACTIC PATTERNS By VINH X. NGHIEM A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS OF THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2009 1 © 2009 Vinh X. Nghiem 2 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I thank my research advisor and supervisory committee chair, Dr. Paul Fishwick for his support, direction, and patience. I also thank my committee members: Dr. Doug Dankel, Dr. Jeff Ho, Dr. Manuel Bermudez, and Dr. Hana Filip for their advice and expertise. Lastly, and mostly, I thank my dear parents for their truly unconditional love. 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .................................................................................................. 3 LIST OF TABLES ............................................................................................................ 6 LIST OF FIGURES .......................................................................................................... 7 ABSTRACT ..................................................................................................................... 8 CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................... 10 1.1 Motivation ....................................................................................................... 10 1.2 Proposed Approach and Issues .................................................................... -

Justifications of Empire in the Fiction of British India

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Honors Program in History (Senior Honors Theses) Department of History 4-20-2007 The White Author's Burden: Justifications of Empire in the Fiction of British India Leslie M. Reich University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/hist_honors Part of the History Commons Reich, Leslie M., "The White Author's Burden: Justifications of Empire in the Fiction of British India" (2007). Honors Program in History (Senior Honors Theses). 4. https://repository.upenn.edu/hist_honors/4 A Senior Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Honors in History. Faculty Advisor: Lisa Mitchell This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/hist_honors/4 For more information, please contact [email protected]. The White Author's Burden: Justifications of Empire in the Fiction of British India Abstract The White Author’s Burden: Justifications of Empire in the Fiction of British India identifies a transformation in Anglo-Indian literature by exploring various fictional works (including novels, short stories, and poems) written by British authors between 1800 and 1924. Before 1857 (the year of the widespread Indian Rebellions that challenged British rule), Anglo-Indian literature focused exclusively on British life in India. Interactions with Indians were minimal, if present at all. After this date, however, British authors began to portray India and Indians almost entirely in ways that justified their own rule. This shift in the literature suggests that the British felt a new need to justify their empire. This thesis focuses on three literary themes offered by British authors that served to legitimize British rule in India in the second half of the nineteenth century: (1) the state of Indian women; (2) the alleged rivalry between Hindus and Muslims; and (3) the perceived incompetence of educated Indians for political rule. -

90Th Cong., 1St Sess., Congressional Record 113 (July 25, 1967)

.' UNITED STATES OF AMERICA th PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 90 CONGRESS FIRST SESSION VOLUME 113-PART 15 JULY 19, 1967, TO JULY 31, 1967 (PAGES 19343 TO 20750) UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON, 1967 July. 25, 1967 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD - SENATE 20193 of highway. Through their efforts along with constitutes one of the highest and most im towards its own Internal integration, to those of engineers ~f Panama and the Bu portant investments of the country. Worthy wards a positive association of all regions reau of Public Roads, the sector of the road of special mention is the outstanding per and all sectors with the active life of prog is being opened approximately nine months formance of Mr. Tomas Guardia who, with ress and socio-economic and political growth ahead of schedule. his consecration, dedication and enthusiasm, that is on an accelerated march towards a On the Panama side, I want to compli contributed as much as anyone else to the future of welfare and prosperity for our ment especially the Panamanian engineers, realization of this project. The Nation owes people. many of whom <have devoted their entire this meritorious citizen a special acknowl May I be permitted to render heartfelt adulthood to the idea and accomplishment edgement for his contribution to the devel tribute to the thousands of laborers, artisans, of the Inter-American Highway. Special opment of the Panamanian road system. I professionals and technicians, both national mention is due to Don Tomas Guardia who must recall also the efforts of such civic and foreign, who have contributed their ef· spent 21 years as Chief Engineer of the Car organizations as the Lions Club and the forts over a p<eriod of several decades to the retera Interamericana. -

Rebellions and Revolutions: China from the 1880S to 2000 Free

FREE REBELLIONS AND REVOLUTIONS: CHINA FROM THE 1880S TO 2000 PDF Jack Gray | 576 pages | 15 May 2003 | Oxford University Press | 9780198700692 | English | Oxford, United Kingdom Rebellions and Revolutions - Jack Gray - Oxford University Press This is a list of revolutions and rebellions. From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. Wikimedia list article. This list is incomplete ; you can help by expanding it. See also: Popular revolt in late medieval Europe. Main article: Atlantic Revolutions. Main article: Latin American wars of independence. List of civil wars List of cultural, intellectual, philosophical and technological revolutions List of guerrillas List of invasions List of peasant revolts List of rebellions in China List of riots List of strikes List of uprisings led by women List of usurpers List of wars of independence national liberation List of women who led a revolt or rebellion List of active communist armed groups Slave rebellion including list of North American slave revolts. Axel Menges ed. Cambridge : Cambridge University Press. Records of the Grand Historian. The Athenian Revolution. Princeton University Press. Bulletin of the Asia Institute. In Chisholm, Hugh ed. Cambridge University Press. The Beginnings of Rome. Ab urbe condita. Epitome of Roman History. The Chinese Strategic Mind. Edward Elgar Publishing. Archived from the original on 3 March Retrieved 8 June Hendrickson Publishers. Chung-chi Journal : 57— Roman History, The foreign Wars. Foreign Wars. History of Rome. Meridin Books. Profile Books LTD. Sulla: A Dictator Reconsidered. The Conspiracy of Catiline. Retrieved 15 February The Oxford Companion to Classical Civilization pp. The Civil Wars. Book LIII. David Cherry. Oxford University Press. Brown Liturgical Press,page The Life of The Twelve Caesars. -

THE PURSUIT of LEGIBLE POLICY: Agency and Participation in the Complex Systems of the Contemporary Megalopolis

GREY CITIES, GREEN INFRASTRUCTURE THE PURSUIT OF LEGIBLE POLICY: Agency and Participation in the Complex Systems of the Contemporary Megalopolis Newton Fund British Council CONACYT IIMAS - UNAM Laboratorio para la Ciudad Future Cities Catapult Superflux Royal College of Art Unidad de Protocolos Buró–Buró GREY CITIES, GREEN INFRASTRUCTURE THE PURSUIT OF LEGIBLE POLICY: Agency and Participation in the Complex Systems of the Contemporary Megalopolis Newton Fund British Council CONACYT IIMAS - UNAM Laboratorio para la Ciudad Future Cities Catapult Superflux Royal College of Art Unidad de Protocolos Buró–Buró The digital publication The Pursuit of Legible Policy: Agency and Participation in the Complex Systems of the Contemporary Megalopolis was conceived with the support of the Newton Fund and is product of the collaboration between the following institutions: The British Council, The Newton Fund, CONACYT, IIMAS - UNAM, Laboratorio para la Ciudad, Future Cities Catapult, Royal College of Art and Superflux. First edition, 2016 Editor Lacey Pipkin Designer Diego Aguirre Fernández Illustrations Juanjo Güitrón Editorial Coordinator Jorge Munguía Matute This electronic publication is for free distribution in its digi- tal presentation. Any printed version of this publication is not recognised by the publisher and is not registered under this ISBN. Digital ISBN of future publication: 978-607-96255-5-9 ©2016 by Buró Buró Oficina de proyectos culturales, S.C.; and the authors, illustrators and photographers. Published by: Buró Buró Oficina de proyectos culturales, S.C. Jalapa 27, Colonia Roma Mexico City, Mexico 06700 buroburo.org Mexico GREY CITIES, GREEN INFRASTRUCTURE THE PURSUIT OF LEGIBLE POLICY: Agency and Participation in the Complex Systems of the Contemporary Megalopolis Iván Abreu | Jon Ardern | Roberto Ascencio | Sofía Bosch | Jorge Camacho | Sergio R. -

The Chinese Government's Implementation of Soft and Hard

Union College Union | Digital Works Honors Theses Student Work 6-2012 The hineseC Government's Implementation of Soft and Hard Power Policies Within Xinjiang and Tibet to Encourage Assimilation Amanda Pace Union College - Schenectady, NY Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses Part of the Asian Studies Commons Recommended Citation Pace, Amanda, "The hineC se Government's Implementation of Soft nda Hard Power Policies Within Xinjiang and Tibet to Encourage Assimilation" (2012). Honors Theses. 928. https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses/928 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Work at Union | Digital Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Union | Digital Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Chinese Government’s Implementation of Soft and Hard Power Policies Within Xinjiang and Tibet to Encourage Assimilation By Amanda Pace ************* Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Honors in the Department of Asian Studies Union College June, 2012 i Abstract PACE, AMANDA: The Chinese Government’s Implementation of Soft and Hard Power Policies Within Xinjiang and Tibet to Encourage Assimilation. Department of Asian Studies, June 2012. ADVISOR: Mark Dallas Today there is an increasing unrest among the minority populations of China and the government enforces different policies both to encourage assimilation and enforce order within minority regions. My research compares two different minority regions in China, Xinjiang and Tibet, and examines Beijing’s education, language and religious policies within these two minority regions. Beijing uses special mechanisms to implement these policies. -

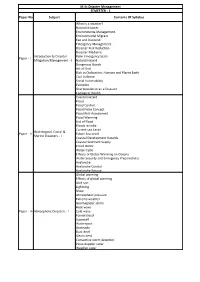

M.Sc Disaster Management SEMESTER - 1 Paper No Subject Contents of Syllabus What Is a Disaster? Natural Disaster

M.Sc Disaster Management SEMESTER - 1 Paper No Subject Contents Of Syllabus What is a disaster? Natural disaster. Environmenta Management. Environmental Migrant. Fee and Dividend. Emergency Management. Disaster Risk Reduction. Disaster Medicine Introduction to Disaster Rohn Emergency Scale. Paper - I Mitigation/Management - I Natural Hazard Dangerous Goods Act of God Risk to Civilization, Humans and Planet Earth. Civil Defense Social Vulnerability Evolution Overpopulation as a Disaster Ecological Health Coastal Hazard Flood Flood Control Flood Pulse Concept Flood Risk Assessment Flood Warming List of Flood Floods in India Current sea Level Hydrological, Costal & Paper - II Future Sea Level Marine Disasters - I Coastal Development Hazards Coastal Sediment Supply Fossil Water Water Cycle Effects of Global Warming on Oceans Water Security and Emergency Preparedness Avalanche Avalanche Control Avalanche Rescue Global warming Effects of global warming Acid rain Lightning Snow Atmospheric pressure Extreme weather Geomagnetic storm Heat wave Paper - III Atmospheric Disasters - I Cold wave Funnel cloud Supercell Waterspout Gustnado Dust devil Steam devil Convective storm detection Pulse-doppler radar Weather radar Geological disaster Tornado Tornadoes of 2012 Tornadogenesis Tornado intensity and damage Enchance fujita scale Fujita scale Torro scale Tornado climatology Tornado records Geological, Mass Mov. & Paper - IV Tornado myths Land Disasters - I Cultural significance of tornadoes Retreat of glaciers since 1850 Geoengineering Earthquake Fault -

Ethnic Riots and Prosocial Behavior: Evidence from Kyrgyzstan

Ethnic Riots and Prosocial Behavior: Evidence from Kyrgyzstan Anselm Hager, Krzysztof Krakowski and Max Schaub∗ Abstract Do ethnic riots affect prosocial behavior? A common view among scholars of ethnic violence is that riots increase cooperation within the warring groups, while cooperation across groups is reduced. We revisit this hypothesis by studying the aftermath of the 2010 Osh riot in Kyrgyzstan, which saw Kyrgyz from outside the city kill over 400 Uzbeks. We implement a representative survey, which includes unobtrusive experimental measures of prosocial behavior. Our causal identification strategy exploits variation in the distance of neighborhoods to armored military ve- hicles, which were instrumental in orchestrating the riot. We find that victimized neighborhoods show substantially lower levels of prosocial behavior. Importantly, we demonstrate that the reduction is similarly stark both within and across groups. Using qualitative interviews, we parse out two mechanisms that help explain the surprising reduction in ingroup prosociality: Victimized Uzbeks felt abandoned by their coethnics, and variation in victimization created a feeling of suspicion. Word count: 11,817 Keywords: Riot; Prosocial Behavior; Ethnic Violence; Central Asia ∗Anselm Hager is Assistant Professor of Political Economy at the Graduate School of Decision Sciences at the University of Konstanz, Universitatsstrasse¨ 10, 78464 Konstanz, Germany. Krzysztof Krakowski is a post-doctoral fellow at the Collegio Carlo Alberto, Piazza V. Arbarello 8, 10122 Turin (TO), Italy. Max Schaub is Research Fellow at the WZB Social Science Center, Reichpietschufer 50, 10785 Berlin, Germany. The authors are grateful for feedback from Delia Baldassari, Paul Bauer, Bernd Beber, Fabrizio Bernardi, Tilman Bruck,¨ Alicia Cooperman, Elias Dinas, James Fearon, Diego Gambetta, Edoardo Grillo, Guy Grossman, Hanno Hilbig, Macartan Humphreys, Joldon Kutmanaliev, Horacio Larreguy, David Laitin, Egor Lazarev, Leonid Peisakhin, Alex Scacco, Jesko Schmoller, Tara Slough, and Jason Wittenberg. -

Stakeholders' Attitudes Towards the Restoration of Agriculture As A

ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I am using this opportunity to express my gratitude to everyone who supported me throughout the course of this Master’s project. I am thankful for their guidance, constructive criticisms and advice during the course of this work. I am sincerely grateful for their insight and illuminating views on a number of issues related to the project. I express my warm thanks to my parents Mr. and Mrs. Mutfwang for their support and guidance. I would also like to thank my project supervisor Dr. Emmanuel Nweke Okafor and Associate Professor Dr. Tatree Nontasak Director MAPD SIAM University and all the people who provided me with the resources to enable the success of my work. iii DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to my uncle, (late) Mr Paul Mutfwang an embodiment of knowledge, you will forever be in our hearts. iv DECLARATION I, Dorcas Tongna Mutfwang hereby declare that this thesis is solely mine and it is original unless acknowledgements verify otherwise. Signature: Name: Dorcas Tongna Mutfwang Date: v LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS AYCF Arewa Youth Consultative Forum FNM Fulani Nationality Movement FAO Food and Agricultural Organisation GTI Global Terrorism Index IDP Internally Displaced Person ILO International Labour Organisation MASSOB Movement for the Actualization of the Sovereign State of Biafra MACBAN Miyetti Allah Cattle Breeders Association of Nigeria MODIS NDVI MODIS Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) NDVF Niger Delta Volunteer Force NST Nigeria Security Tracker OPC Oodua People’s Congress UNHCR United Nations High Commission for Refugees UN United Nations UNSDG United Nations Sustainable Development Goals vi TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT .............................................................................................................................. -

Guide to Material at the LBJ Library Pertaining to Civil Rights

LYNDON BAINES JOHNSON L I B R A R Y & M U S E U M www.lbjlibrary.org 5/94 (updated 11/07) HU 2 (rev. 6/10, 9/10, 7/11) LE/HU 2 MATERIAL AT THE LBJ LIBRARY PERTAINING TO CIVIL RIGHTS This list includes files in the Johnson Library that contain material relating to Civil Rights. It is not definitive, however, and researchers should seek out other potentially useful files. The guide includes those collections which have been opened for research in part or in whole, and those collections which are currently unprocessed or unavailable. See also the guides: Affirmative Action; Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas, 1954; Civil Rights Act of 1964; Civil and Racial Disturbances; Fair Housing Act of 1968;The F.B.I., J. Edgar Hoover, Surveillance and Privacy; Mexican-Americans; Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP); Race Relations in the Armed Forces, 1965-69; Racial Integration of the Air Force; The 1965 Voting Rights Act and the Violence in Selma, Alabama; Women. WHITE HOUSE CENTRAL FILES (WHCF), SUBJECT FILE This permanent White House office was the main filing unit during the Johnson presidency, though not the primary one for foreign policy documents. Material was filed under 60 major subject headings, descriptions of which are in the WHCF finding aid. FG, Federal Government-Organizations Box # FG 11-15, Office of Economic Opportunity 124-28 FG 11-15-1, Job Corps 129-30 FG 11-15-2, National Advisory Council on Economic Opportunity 130 FG 110-4, Coast Guard 153-54 FG 120-7, Women's Army Corps 174 FG 125-5, Marine Corps (includes women) 178-79 FG 125-6, WAVES 179 FG 130-7, Women of the Air Force 183 FG 135-9, Dept.