Fritz and Adolf Busch and Rudolf Serkin Play Max Reger’S Music in the English-Speaking Lands

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Brahms Symphony 2 Gardiner

Brahms Symphony 2 Gardiner 1 Johannes Brahms 1833-1897 1 Alto Rhapsody Op.53 (1869) 12:57 Franz Schubert 1797-1828 2 Gesang der Geister über den Wassern D714 (1821) 12:18 3 Gruppe aus dem Tartarus D583 (1817, arr. Brahms 1871) 2:20 4 An Schwager Kronos D369 (1816, arr. Brahms 1871) 2:28 Symphony No.2 in D major Op.73 (1877) 5 I Allegro non troppo 19:42 6 II Adagio non troppo – L’istesso tempo, ma grazioso 9:28 7 III Allegretto grazioso (quasi andantino) – Presto ma non assai – Tempo I 5:06 8 IV Allegro con spirito 9:05 73:59 Nathalie Stutzmann contralto Orchestre Révolutionnaire et Romantique The Monteverdi Choir John Eliot Gardiner Recorded live at the Salle Pleyel, Paris, November 2007 2 Brahms: Roots and memory John Eliot Gardiner To me Brahms’ large-scale music is brimful of vigour, drama and a driving passion. ‘Fuego y cristal’ was how Jorge Luis Borges once described it. How best to release all that fire and crystal, then? One way is to set his symphonies in the context of his own superb and often neglected choral music, and that of the old masters he particularly cherished (Schütz and Bach especially) and of recent heroes of his (Mendelssohn, Schubert and Schumann). This way we are able to gain a new perspective on his symphonic compositions, drawing attention to the intrinsic vocality at the heart of his writing for orchestra. Composing such substantial choral works as the Schicksalslied, the Alto Rhapsody, Nänie and the German Requiem gave Brahms invaluable experience of orchestral writing years before he brought his first symphony to fruition: they were the vessels for some of his most profound thoughts, revealing at times an almost desperate urge to communicate things of import. -

TOC 0245 CD Booklet.Indd

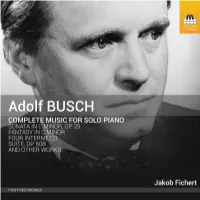

ADOLF BUSCH AND THE PIANO by Jakob Fichert It’s hardly a secret that Adolf Busch (1891–1952) was one of the greatest violinists of the twentieth century. But only specialists, it seems, are aware that he was also a very fne composer, even though these two artistic identities – performer and composer – were of equal importance to him. In recent years some of his chamber works, his organ music and parts of his symphonic œuvre have been recorded, allowing some appreciation of his stature as a creative fgure. But Busch’s music for solo piano has yet to be discovered – only the Andante espressivo, BoO1 37 22 , has been recorded before now, by Peter Serkin, Busch’s grandson, and that in a private recording, not available commercially. Tis album therefore presents the entirety of Busch’s piano output for the frst time. Busch’s writing for solo piano forms a kind of huge triptych, with the Sonata in C minor, Op. 25, as its central panel; another major work, a Fantasia in C major, BoO 20, was written early in his career; and a later Suite, Op. 60b, dates from the time of his full maturity. Busch also wrote more than a dozen smaller piano pieces, in which he seems to have experimented with various genres in pursuit of the development of his musical language, with four Intermezzi, a Scherzo and other character pieces among them. One can hear the infuence of Brahms, Mendelssohn, Busoni and – especially – Reger, but with familiarity Busch’s style can be heard to be distinctive and personal, displaying a unique and highly expressive world of sound. -

Staatskapelle Dresden

Staatskapelle Dresden Staatskapelle Dresden Matthias Claudi PR und Marketing Theaterplatz 2 Christian Thielemann, Principal Conductor 01067 Dresden Germany Myung-Whun Chung, Principal Guest Conductor T 0351 4911 380 herberb Blomstedt, Conductor Laureate F 0351 4911 328 [email protected] Founded by Prince Elector Moritz von Sachsen in 1548, the Staatskapelle Dresden is one of the oldest orchestras in the world and steeped in tradition. Over its long history many distinguished conductors and internationally celebrated instrumentalists have left their mark on this onetime court orchestra. Previous directors include Heinrich Schütz, Johann Adolf Hasse, Carl Maria von Weber and Richard Wagner, who called the ensemble his »miraculous harp«. The list of prominent conductors of the last 100 years includes Ernst von Schuch, Fritz Reiner, Fritz Busch, Karl Böhm, Joseph Keilberth, Rudolf Kempe, Otmar Suitner, Kurt Sanderling, Herbert Blomstedt and Giuseppe Sinopoli. The orchestra was directed by Bernard Haitink from 2002-2004 and most recently by Fabio Luisi from 2007-2010. Principal Conductor since the 2012 / 2013 season has been Christian Thielemann. In May 2016 the former Principal Conductor Herbert Blomstedt received the title Conductor Laureate. This title has only been awarded to Sir Colin Davis before, who held it from 1990 until his death in April 2013. Myung-Whun Chung has been Principal Guest Conductor since the 2012 / 2013 season. Richard Strauss and the Staatskapelle were closely linked for more than sixty years. Nine of the composer’s operas were premiered in Dresden, including »Salome«, »Elektra« and »Der Rosenkavalier«, while Strauss’s »Alpine Symphony« was dedicated to the orchestra. Countless other famous composers have written works either dedicated to the orchestra or first performed in Dresden. -

Carnegie Hall

CARNEGIE HALL 136-2-1E-43 ALFRED SCOTT, Publisher. 156 Fifth Avenue. New York &njoy these supreme moments oj music again ancl again in pour own home, on VICTORS RECORDS Hear these brilliant interpretations of ARTUR RUBINSTEIN TSCHAIKOWSKY -CONCERTO NO. 1, IN B FLAT MINOR, Op. 23. With the London Symphony Orchestra, John Barbirolli, conductor. Album DM-180 $4.50* GRIEG—CONCERTO IN A MINOR, Op. 16. With the Philadelphia Orchestra, Eugene Ormandy, conductor. Album DM-900 $3.50* BRAHMS — INTERMEZZI AND RHAPSODIES. Album M-893 $4.50* SCHUBERT — TRIO NO. 1, IN B FLAT MAJOR, Op. 99. With Jascha Heifetz, violinist and Emanuel Feuermann, ’cellist. Album DM-923 $4.50* CHOPIN—CONCERTO NO. 1, IN E MINOR, Op. 11 With the London Symphony Orchestra, John Barbirolli, conductor. Album DM-418 $4.50* CHOPIN — MAZURKAS (complete in 3 volumes) Album M-626, Vol. 1 $5.50* Album M-656, Vol. 2 $5.50" Album M-691, Vol. 3 $4.50* •Suggested list prices exclusive of excise tax. Listen to the Victor Red Seal Records programs on Station WEAR at 11:15 P.M., Monday through Friday and Station WQXR at 10 to 10:30 P.M., Monday, Wednesday and Friday. Keep Going With Music • Buy War Bonds Every Pay Day The world's greatest artists are on Victor Records Carnegie Hall Program BUY WAR BONDS AND STAMPS 9 it heard If you have a piano which you would care to donate for the duration of the War kindly communicate with Carnegie Hall Recreation Unit for men of the United Nations, Studio 603 Carnegie Hall. -

View PDF Online

MARLBORO MUSIC 60th AnniversAry reflections on MA rlboro Music 85316_Watkins.indd 1 6/24/11 12:45 PM 60th ANNIVERSARY 2011 MARLBORO MUSIC Richard Goode & Mitsuko Uchida, Artistic Directors 85316_Watkins.indd 2 6/23/11 10:24 AM 60th AnniversA ry 2011 MARLBORO MUSIC richard Goode & Mitsuko uchida, Artistic Directors 85316_Watkins.indd 3 6/23/11 9:48 AM On a VermOnt HilltOp, a Dream is BOrn Audience outside Dining Hall, 1950s. It was his dream to create a summer musical community where artists—the established and the aspiring— could come together, away from the pressures of their normal professional lives, to exchange ideas, explore iolinist Adolf Busch, who had a thriving music together, and share meals and life experiences as career in Europe as a soloist and chamber music a large musical family. Busch died the following year, Vartist, was one of the few non-Jewish musicians but Serkin, who served as Artistic Director and guiding who spoke out against Hitler. He had left his native spirit until his death in 1991, realized that dream and Germany for Switzerland in 1927, and later, with the created the standards, structure, and environment that outbreak of World War II, moved to the United States. remain his legacy. He eventually settled in Vermont where, together with his son-in-law Rudolf Serkin, his brother Herman Marlboro continues to thrive under the leadership Busch, and the great French flutist Marcel Moyse— of Mitsuko Uchida and Richard Goode, Co-Artistic and Moyse’s son Louis, and daughter-in-law Blanche— Directors for the last 12 years, remaining true to Busch founded the Marlboro Music School & Festival its core ideals while incorporating their fresh ideas in 1951. -

Adolf Busch: the Life of an Honest Musician (2 Volume Set) Online

yiMmZ (Ebook pdf) Adolf Busch: The Life of an Honest Musician (2 Volume Set) Online [yiMmZ.ebook] Adolf Busch: The Life of an Honest Musician (2 Volume Set) Pdf Free Tully Potter DOC | *audiobook | ebooks | Download PDF | ePub Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook #3756817 in Books Toccata Press 2010-09-17Original language:EnglishPDF # 1 3.97 x 7.32 x 9.02l, 7.55 #File Name: 09076895071408 pagesthe life and times of Adolf Busch, the "honest musician" | File size: 43.Mb Tully Potter : Adolf Busch: The Life of an Honest Musician (2 Volume Set) before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised Adolf Busch: The Life of an Honest Musician (2 Volume Set): 9 of 10 people found the following review helpful. An Exemplary Life and Musical History of the TimesBy Edgar SelfLong awaited, this biography of violinist, composer, quartet and trio leader, teacher, and conductor Adolf Busch (1891-1952), co-founder of the Marlboro School of Music, is a history of the violin, of concerts and chamber-music in the first half of the 20th century. The texts, research notes, copious illustrations, and appendices detail virtually every concert and associate of Busch's life with full descriptions of his musical and personal relations with Reger, Busoni, Tovey, Roentgens and hundreds of others, including those unsympathetic to him such as Furtwaengler, Sibelius, Edwin Fischer, and Elly Ney, for musical or political reasons. Busch's early immigration from Germany and his part in creating the Lucerne Festival and Palestine Symphony Orchestra, precursor of the Israel Philharmonic, before settling in the U.S. -

Symposium Records Cd 1109 Adolf Busch

SYMPOSIUM RECORDS CD 1109 The Great Violinists – Volume 4 ADOLF BUSCH (1891-1952) This compact disc documents the early instrumental records of the greatest German-born musician of this century. Adolf Busch was a legendary violinist as well as a composer, organiser of chamber orchestras, founder of festivals, talented amateur painter and moving spirit of three ensembles: the Busch Quartet, the Busch Trio and the Busch/Serkin Duo. He was also a great man, who almost alone among German gentile musicians stood out against Hitler. His concerts between the wars inspired a generation of music-lovers and musicians; and his influence continued after his death through the Marlboro Festival in Vermont, which he founded in 1950. His associate and son-in-law, Rudolf Serkin (1903-1991) maintained it until his own death, and it is still going strong. Busch's importance as a fiddler was all the greater, because he was the last glory of the short-lived German school; Georg Kulenkampff predeceased him and Hitler's decade smashed the edifice built up by men like Joseph Joachim and Carl Flesch. Adolf Busch's career was interrupted by two wars; and his decision to boycott his native country in 1933, when he could have stayed and prospered as others did, further fractured the continuity of his life. That one action made him an exile, cost him the precious cultural nourishment of his native land and deprived him of his most devoted audience. Five years later, he renounced all his concerts in Italy in protest at Mussolini's anti-semitic laws. -

The Busch Quartet Beethoven Volume 4 Mp3, Flac, Wma

The Busch Quartet Beethoven Volume 4 mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Classical Album: Beethoven Volume 4 Country: UK Released: 2009 Style: Classical MP3 version RAR size: 1345 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1648 mb WMA version RAR size: 1589 mb Rating: 4.6 Votes: 721 Other Formats: TTA XM DMF AHX AU AUD APE Tracklist Quartet No.13 In B Flat Op.130 1 I: Adagio Ma non Troppo 8:56 2 II: Presto 1:54 3 III: Andante Con Moto, Ma Non Troppo 5:23 4 IV: Alla Danza Tedesca: Allegro Assai 2:23 5 V. Cavatina: Adagio Molto Espressivo 7:00 6 VI. Finale: Allegro 8:27 Quartet No.15 In A Minor Op.132 7 I: Assai Sostenuto - Allegro 4:03 8 II: Allegro Ma Non Tanto 6:15 III: Heilger Dankesang Eines Genesenen An Die Gottheit, In Der 9 3:45 Lydischen Tonart: Molto Adagio - Andante - Mit Innigster EmpFundung 10 IV: Alla Marcia, Assai Vivace 4:26 11 V. Allegro Appassionato Companies, etc. Phonographic Copyright (p) – Dutton Recorded At – Abbey Road Studios Credits Cello – Herman Busch* Composed By – Ludwig van Beethoven Ensemble – The Busch Quartet Liner Notes – Tully Potter Remastered By – Michael Dutton* Viola – Karl Doktor Violin – Adolph Busch, Gösta Andreasson (tracks: Gösta Andreassen) Notes Tracks 1 to 6: Recorded at Liederkranz Hall, NY 13 & 16 June 1941 Tracks 7 to 11: Recorded at Abbey Road Studio no. 3, on 7 October 1937 Barcode and Other Identifiers Barcode: 7 65387 97942 3 Rights Society: MCPS SPARS Code: ADD Matrix / Runout: [Manufactured by kdg] 672.658 CDBP 9794 Mould SID Code: IFPI 3066 Related Music albums to Beethoven Volume 4 by The Busch Quartet Mendelssohn – Pacifica Quartet - The Complete String Quartets Beethoven - Alban Berg Quartett - Complete String Quartets Artur Schnabel, Ludwig van Beethoven - Beethoven the Complete Piano Sonatas on Thirteen Discs Beethoven, Paul Lewis - Complete Piano Sonatas John Lill - Beethoven Piano Sonatas Complete Vol I Beethoven, Juilliard String Quartet - Quartet In A Minor Op. -

Persecution, Collaboration, Resistance

Münsteraner Schriften zur zeitgenössischen Musik 5 Ina Rupprecht (ed.) Persecution, Collaboration, Resistance Music in the ›Reichskommissariat Norwegen‹ (1940–45) Münsteraner Schrift en zur zeitgenössischen Musik Edited by Michael Custodis Volume 5 Ina Rupprecht (ed.) Persecution, Collaboration, Resistance Music in the ‘Reichskommissariat Norwegen’ (1940–45) Waxmann 2020 Münster x New York The publication was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft , the Grieg Research Centre and the Westfälische Wilhelms-Universität Münster as well as the Open Access Publication Fund of the University of Münster. Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek Th e Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografi e; detailed bibliographic data are available in the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de Münsteraner Schrift en zur zeitgenössischen Musik, Volume 5 Print-ISBN 978-3-8309-4130-9 E-Book-ISBN 978-3-8309-9130-4 DOI: https://doi.org/10.31244/9783830991304 CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 Waxmann Verlag GmbH, 2020 Steinfurter Straße 555, 48159 Münster www.waxmann.com [email protected] Cover design: Pleßmann Design, Ascheberg Cover pictures: © Hjemmefrontarkivet, HA HHI DK DECA_0001_44, saddle of sources regarding the Norwegian resistance; Riksarkivet, Oslo, RA/RAFA-3309/U 39A/ 4/4-7, img 197, Atlantic Presse- bilderdienst 12. February 1942: Th e newly appointed Norwegian NS prime minister Vidkun Quisling (on the right) and Reichskomissar Josef Terboven (on the left ) walking along the front of an honorary -

Digital Booklet Porgy & Bess

71 TRACKS THE AMADEUS QUARtet ReCORDINGS VOL. I BEETHOVEN Berlin, 1950-1967 recording producer: Wolfgang Gottschalk (Op. 127) Hartung (Op. 59, 2) Hermann Reuschel (Op. 18, 2-5 / Op. 59, 1 / Op. 130-133 / Op. 135 / Op. 29) Salomon (Op. 18, 1+6 / Op. 59, 3 / Op. 95) recording engineer: Siegbert Bienert (Op. 18, 5 / Op. 130-133 / Op. 29) Peter Burkowitz (Op. 18, 6) THE Heinz Opitz (Op. 18, 2 / Op. 59, 1+2 / Op. 127 / Op. 135) Preuss (Op. 18, 1 / Op. 59, 3 / Op. 95) Alfred Steinke (Op. 18, 3+4) AMADEUS QUARtet ReCORDinGS Berlin, 1950-1967 Eine Aufnahme von RIAS Berlin (lizenziert durch Deutschlandradio) recording: P 1950 - 1967 Deutschlandradio research: Rüdiger Albrecht remastering: P 2013 Ludger Böckenhoff rights: audite claims all rights arising from copyright law and competition law in relation to research, compilation and re-mastering of the original audio tapes, VOL. I BEETHOVEN as well as the publication of this CD. Violations will be prosecuted. The historical publications at audite are based, without exception, on the original tapes from broadcasting archives. In general these are the original analogue tapes, MstASTER RELEASE which attain an astonishingly high quality, even measured by today’s standards, with their tape speed of up to 76 cm/sec. The remastering – professionally com- petent and sensitively applied – also uncovers previously hidden details of the interpretations. Thus, a sound of superior quality results. CD publications based 1 on private recordings from broadcasts cannot be compared with these. AMADEUS-QUARtett further reading: Daniel Snowman: The Amadeus Quartet. The Men and the Music, violin I Norbert Brainin Robson Books (London, 1981) violin II Siegmund Nissel Gerd Indorf: Beethovens Streichquartette, Rombach Verlag (Freiburg i. -

MOZART Piano Quartets Nos. 1 and 2 Clarinet Quintet

111238 bk Szell-Goodman EU 11/10/06 1:50 PM Page 5 MOZART: Quartet No. 1 in G minor for Piano and Strings, K. 478 20:38 1 Allegro 7:27 2 Andante 6:37 MOZART 3 Rondo [Allegro] 6:34 Recorded 18th August, 1946 in Hollywood Matrix nos.: XCO 36780 through 36785. Piano Quartets Nos. 1 and 2 First issued on Columbia 72624-D through 72626-D in album M-773 MOZART: Quartet No. 2 in E flat major for Piano and Strings, K. 493 21:58 Clarinet Quintet 4 Allegro 7:17 AN • G 5 Larghetto 6:44 DM EO 6 O R Allegro 7:57 Also available O G Recorded 20th August, 1946 in Hollywood G E Matrix nos.: XCO 36786 through 36791. Y S Z First issued on Columbia 71930-D through 71932-D in album M-669 N E N L George Szell, Piano E L Members of the Budapest String Quartet B (Joseph Roisman, Violin; Boris Kroyt, Viola; Mischa Schneider, Cello) MOZART: Quintet in A major for Clarinet and Strings, K. 581 27:20 7 Allegro 6:09 8 Larghetto 5:42 9 Menuetto 6:29 0 Allegretto con variazioni 9:00 Recorded 25th April, 1938 in New York City Matrix nos.: BS 022904-2, 022905-2, 022902-2, 022903-1, 022906-1, 022907-1 1 93 gs and CS 022908-2 and 022909-1. 8-1 rdin First issued on Victor 1884 through 1886 and 14921 in album M-452 946 Reco 8.110306 8.110307 Benny Goodman, Clarinet Budapest String Quartet (Joseph Roisman, Violin I; Alexander Schneider, Violin II, Boris Kroyt, Viola; Mischa Schneider, Cello) Budapest String Quartet Producer and Audio Restoration Engineer: Mark Obert-Thorn Joseph Roisman • Alexander Schneider, Violins Boris Kroyt, Viola Mischa Schneider, Cello 8.111238 5 8.111238 6 111238 bk Szell-Goodman EU 11/10/06 1:50 PM Page 2 Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791): become more apparent than its failings. -

ARSC Journal

HISTORIC VOCAL RECORDINGS STARS OF THE VIENNA OPERA (1946-1953): MOZART: Die Entfuhrung aus dem Serail--Wer ein Liebchen hat gafunden. Ludwig Weber, basso (Felix Prohaska, conductor) ••.• Konstanze ••• 0 wie angstlich; Wenn der Freude. Walther Ludwig, tenor (Wilhelm Loibner) •••• 0, wie will ich triumphieren. Weber (Prohaska). Nozze di Figaro--Non piu andrai. Erich Kunz, baritone (Herbert von Karajan) •••• Voi che sapete. Irmgard Seefried, soprano (Karajan) •••• Dove sono. Elisabeth Schwarzkopf, soprano (Karajan) . ..• Sull'aria. Schwarzkopf, Seefried (Karajan). .• Deh vieni, non tardar. Seefried (Karajan). Don Giovanni--Madamina, il catalogo e questo. Kunz (Otto Ackermann) •••• Laci darem la mano. Seefried, Kunz (Karajan) • ••• Dalla sua pace. Richard Tauber, tenor (Walter Goehr) •••• Batti, batti, o bel Masetto. Seefried (Karajan) •.•• Il mio tesoro. Tauber (Goehr) •••• Non mi dir. Maria Cebotari, soprano (Karajan). Zauberfl.Ote- Der Vogelfanger bin ich ja. Kunz (Karajan) •••• Dies Bildnis ist be zaubernd schon. Anton Dermota, tenor (Karajan) •••• 0 zittre nicht; Der Holle Rache. Wilma Lipp, soprano (Wilhelm Furtwangler). Ein Miidchen oder Weibchen. Kunz (Rudolf Moralt). BEETHOVEN: Fidelio--Ach war' ich schon. Sena Jurinac, soprano (Furtwangler) •••• Mir ist so wunderbar. Martha Modl, soprano; Jurinac; Rudolf Schock, tenor; Gottlob Frick, basso (Furtwangler) •••• Hat man nicht. Weber (Prohaska). WEBER: Freischutz--Hier im ird'schen Jammertal; Schweig! Schweig! Weber (Prohaska). NICOLAI: Die lustigen Weiher von Windsor--Nun eilt herbei. Cebotari {Prohaska). WAGNER: Meistersinger--Und doch, 'swill halt nicht gehn; Doch eines Abends spat. Hans Hotter, baritone (Meinhard von Zallinger). Die Walkilre--Leb' wohl. Hotter (Zallinger). Gotterdammerung --Hier sitz' ich. Weber (Moralt). SMETANA: Die verkaufte Braut--Wie fremd und tot. Hilde Konetzni, soprano (Karajan). J. STRAUSS: Zigeuner baron--0 habet acht.