Bicycling and Violence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tribes and Empire on the Margins of Nineteenth-Century Iran

publications on the near east publications on the near east Poetry’s Voice, Society’s Song: Ottoman Lyric The Transformation of Islamic Art during Poetry by Walter G. Andrews the Sunni Revival by Yasser Tabbaa The Remaking of Istanbul: Portrait of an Shiraz in the Age of Hafez: The Glory of Ottoman City in the Nineteenth Century a Medieval Persian City by John Limbert by Zeynep Çelik The Martyrs of Karbala: Shi‘i Symbols The Tragedy of Sohráb and Rostám from and Rituals in Modern Iran the Persian National Epic, the Shahname by Kamran Scot Aghaie of Abol-Qasem Ferdowsi, translated by Ottoman Lyric Poetry: An Anthology, Jerome W. Clinton Expanded Edition, edited and translated The Jews in Modern Egypt, 1914–1952 by Walter G. Andrews, Najaat Black, and by Gudrun Krämer Mehmet Kalpaklı Izmir and the Levantine World, 1550–1650 Party Building in the Modern Middle East: by Daniel Goffman The Origins of Competitive and Coercive Rule by Michele Penner Angrist Medieval Agriculture and Islamic Science: The Almanac of a Yemeni Sultan Everyday Life and Consumer Culture by Daniel Martin Varisco in Eighteenth-Century Damascus by James Grehan Rethinking Modernity and National Identity in Turkey, edited by Sibel Bozdog˘an and The City’s Pleasures: Istanbul in the Eigh- Res¸at Kasaba teenth Century by Shirine Hamadeh Slavery and Abolition in the Ottoman Middle Reading Orientalism: Said and the Unsaid East by Ehud R. Toledano by Daniel Martin Varisco Britons in the Ottoman Empire, 1642–1660 The Merchant Houses of Mocha: Trade by Daniel Goffman and Architecture in an Indian Ocean Port by Nancy Um Popular Preaching and Religious Authority in the Medieval Islamic Near East Tribes and Empire on the Margins of Nine- by Jonathan P. -

In the Lands of the Romanovs: an Annotated Bibliography of First-Hand English-Language Accounts of the Russian Empire

ANTHONY CROSS In the Lands of the Romanovs An Annotated Bibliography of First-hand English-language Accounts of The Russian Empire (1613-1917) OpenBook Publishers To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/268 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. In the Lands of the Romanovs An Annotated Bibliography of First-hand English-language Accounts of the Russian Empire (1613-1917) Anthony Cross http://www.openbookpublishers.com © 2014 Anthony Cross The text of this book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license (CC BY 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the text; to adapt it and to make commercial use of it providing that attribution is made to the author (but not in any way that suggests that he endorses you or your use of the work). Attribution should include the following information: Cross, Anthony, In the Land of the Romanovs: An Annotated Bibliography of First-hand English-language Accounts of the Russian Empire (1613-1917), Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2014. http://dx.doi.org/10.11647/ OBP.0042 Please see the list of illustrations for attribution relating to individual images. Every effort has been made to identify and contact copyright holders and any omissions or errors will be corrected if notification is made to the publisher. As for the rights of the images from Wikimedia Commons, please refer to the Wikimedia website (for each image, the link to the relevant page can be found in the list of illustrations). -

LOS ANGELES CAPITAL GLOBAL FUNDS PLC Interim Report and Unaudited Condensed Financial Statements for the Financial Half Year End 31St December, 2020

LOS ANGELES CAPITAL GLOBAL FUNDS PLC Interim Report and Unaudited Condensed Financial Statements For the financial half year end 31st December, 2020 Company Registration No. 499159 LOS ANGELES CAPITAL GLOBAL FUNDS PLC Table of Contents Page Management and Administration 1 General Information 2 Investment Manager’s Report 3-4 Condensed Statement of Financial Position 5-6 Condensed Statement of Comprehensive Income 7-8 Condensed Statement of Changes in Net Assets Attributable to Holders of Redeemable Participating Shares 9-10 Condensed Statement of Cash Flows 11-12 Notes to the Condensed Financial Statements 13-21 Los Angeles Capital Global Funds PLC - Los Angeles Capital Global Fund Schedule of Investments 22-31 Statement of Changes in the Portfolio 32-33 Appendix I 34 LOS ANGELES CAPITAL GLOBAL FUNDS PLC Management and Administration DIRECTORS REGISTERED OFFICE Ms. Edwina Acheson (British) 30 Herbert Street Mr. Daniel Allen (American) Dublin 2 Mr. David Conway (Irish)* D02 W329 Mr. Desmond Quigley (Irish)* Ireland Mr. Thomas Stevens (American) * Independent COMPANY SECRETARY LEGAL ADVISERS Simmons & Simmons Corporate Services Limited Simmons & Simmons Waterways House Waterways House Grand Canal Quay Grand Canal Quay Dublin Dublin D02 NF40 D02 NF40 Ireland Ireland INVESTMENT MANAGER CHARTERED ACCOUNTANTS AND Los Angeles Capital Management and Equity STATUTORY AUDIT FIRM Research Inc.* Grant Thornton 11150 Santa Monica Boulevard 13-18 City Quay Suite 200 Dublin 2 Los Angeles D02 ED70 California 90025 Ireland USA * since 1st January, 2021 name has changed to Los Angeles Capital Management LLC MANAGEMENT COMPANY DEPOSITARY DMS Investment Management Services (Europe) Limited* Brown Brothers Harriman Trustee 76 Lower Baggot Street Services (Ireland) Limited Dublin 2 30 Herbert Street D02 EK81 Dublin 2 Ireland D02 W329 Ireland * since 29th July, 2020 ADMINISTRATOR, REGISTRAR AND DISTRIBUTOR TRANSFER AGENT LACM Global, Ltd. -

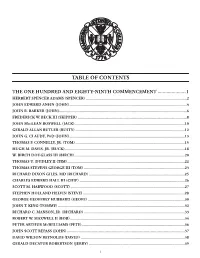

Table of Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS THE ONE HUNDRED AND EIGHTY-NINTH COMMENCEMENT ......................1 HERBERT SPENCER ADAMS (SPENCER) ...................................................................................................2 JOHN EDWARD ANFIN (JOHN) ...................................................................................................................4 JOHN R. BARKER (JOHN) .............................................................................................................................6 FREDERICK W. BECK III (SKIPPER) ...........................................................................................................8 JOHN MACLEAN BOSWELL (JACK) ............................................................................................................10 GERALD ALLAN BUTLER (RUSTY) ...........................................................................................................12 JOHN G. CLAUDY, PHD (JOHN) .................................................................................................................13 THOMAS F. CONNELLY, JR. (TOM) ...........................................................................................................15 HUGH M. DAVIS, JR. (BUCK) .....................................................................................................................18 W. BIRCH DOUGLASS III (BIRCH) ............................................................................................................20 THOMAS U. DUDLEY II (TIM) ...................................................................................................................22 -

Armenian Orchestral Music Tigran Arakelyan a Dissertation Submitted

Armenian Orchestral Music Tigran Arakelyan A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts University of Washington 2016 Reading Committee: David Alexander Rahbee, Chair JoAnn Taricani Timothy Salzman Program Authorized to Offer Degree: School of Music ©Copyright 2016 Tigran Arakelyan University of Washington Abstract Armenian Orchestral Music Tigran Arakelyan Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Dr. David Alexander Rahbee School of Music The goal of this dissertation is to make available all relevant information about orchestral music by Armenian composers—including composers of Armenian descent—as well as the history pertaining to these composers and their works. This dissertation will serve as a unifying element in bringing the Armenians in the diaspora and in the homeland together through the power of music. The information collected for each piece includes instrumentation, duration, publisher information, and other details. This research will be beneficial for music students, conductors, orchestra managers, festival organizers, cultural event planning and those studying the influences of Armenian folk music in orchestral writing. It is especially intended to be useful in searching for music by Armenian composers for thematic and cultural programing, as it should aid in the acquisition of parts from publishers. In the early part of the 20th century, Armenian people were oppressed by the Ottoman government and a mass genocide against Armenians occurred. Many Armenians fled -

Inventory of the Henry M. Stanley Archives Revised Edition - 2005

Inventory of the Henry M. Stanley Archives Revised Edition - 2005 Peter Daerden Maurits Wynants Royal Museum for Central Africa Tervuren Contents Foreword 7 List of abbrevations 10 P A R T O N E : H E N R Y M O R T O N S T A N L E Y 11 JOURNALS AND NOTEBOOKS 11 1. Early travels, 1867-70 11 2. The Search for Livingstone, 1871-2 12 3. The Anglo-American Expedition, 1874-7 13 3.1. Journals and Diaries 13 3.2. Surveying Notebooks 14 3.3. Copy-books 15 4. The Congo Free State, 1878-85 16 4.1. Journals 16 4.2. Letter-books 17 5. The Emin Pasha Relief Expedition, 1886-90 19 5.1. Autograph journals 19 5.2. Letter book 20 5.3. Journals of Stanley’s Officers 21 6. Miscellaneous and Later Journals 22 CORRESPONDENCE 26 1. Relatives 26 1.1. Family 26 1.2. Schoolmates 27 1.3. “Claimants” 28 1 1.4. American acquaintances 29 2. Personal letters 30 2.1. Annie Ward 30 2.2. Virginia Ambella 30 2.3. Katie Roberts 30 2.4. Alice Pike 30 2.5. Dorothy Tennant 30 2.6. Relatives of Dorothy Tennant 49 2.6.1. Gertrude Tennant 49 2.6.2. Charles Coombe Tennant 50 2.6.3. Myers family 50 2.6.4. Other 52 3. Lewis Hulse Noe and William Harlow Cook 52 3.1. Lewis Hulse Noe 52 3.2. William Harlow Cook 52 4. David Livingstone and his family 53 4.1. David Livingstone 53 4.2. -

Consolidated Contents of the American Genealogist

Consolidated Contents of The American Genealogist Volumes 9-85; July, 1932 - October, 2011 Compiled by, and Copyright © 2010-2013 by Dale H. Cook This index is made available at americangenealogist.com by express license of Mr. Cook. The same material is also available on Mr. Cook’s own website, among consolidated contents listings of other periodicals created by Mr. Cook, available on the following page: plymouthcolony.net/resources/periodicals.html This consolidated contents listing is for personal non-commercial use only. Mr. Cook may be reached at: [email protected] This file reproduces Mr. Cook’s index as revised August 22, 2013. A few words about the format of this file are in order. The first eight volumes of Jacobus' quarterly are not included. They were originally published under the title The New Haven Genealogical Magazine, and were consolidated and reprinted in eight volumes as as Families of Ancient New Haven (Rome, NY: Clarence D. Smith, Printer, 1923-1931; reprinted in three volumes with 1939 index Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Co., 1974). Their focus was upon the early families of that area, which are listed in alphabetical order. With a few exceptions this file begins with the ninth volume, when the magazine's title was changed to The American Genealogist and New Haven Genealogical Magazine and its scope was expanded. The title was shortened to The American Genealogist in 1937. The entries are listed by TAG volume. Each volume is preceded by the volume number and year(s) in boldface. Articles that are carried across more than one volume have their parts listed under the applicable volumes. -

Central-Eastern European Loess Sources Central- Och Östeuropeiska Lössursprung

Independent Project at the Department of Earth Sciences Självständigt arbete vid Institutionen för geovetenskaper 2020: 8 Central-Eastern European Loess Sources Central- och östeuropeiska lössursprung Hanna Gaita DEPARTMENT OF EARTH SCIENCES INSTITUTIONEN FÖR GEOVETENSKAPER Independent Project at the Department of Earth Sciences Självständigt arbete vid Institutionen för geovetenskaper 2020: 8 Central-Eastern European Loess Sources Central- och östeuropeiska lössursprung Hanna Gaita Copyright © Hanna Gaita Published at Department of Earth Sciences, Uppsala University (www.geo.uu.se), Uppsala, 2020 Sammanfattning Central- och östeuropeiska lössursprung Hanna Gaita Klimatförändringar är idag en av våra högst prioriterade utmaningar. Men för att förstå klimatförändringar och kunna göra förutsägelser om framtiden är kunskap om tidigare klimat av väsentlig betydelse. Nyckelarkivet för tidigare klimatförändringar kan studeras genom så kallade lössavlagringar. Denna artikel undersöker lösskällor i Europa och hur dess avlagringar kan berätta för oss om olika ursprung med hjälp av olika geokemiska tekniker och metoder. Sekundära uppgifter om lössavlagringar och källor över Central- och Östeuropa har samlats in och undersökts för att testa några av de möjliga huvudsakliga stoftkällområdena för europeiska lössavlag- ringar som har föreslagits av andra forskare. Olika tekniker och metoder används för att undersöka lössediment när man försöker identifiera deras ursprung. Generellt kan tekniker och metoder delas in i några av följande geokemiska och analytiska parametrar: XRD (röntgendiffraktion) och XRF (röntgenfluorescensspektrometri), grundämnesför- hållanden, Sr-Nd isotopanalyser, zirkon U-Pb geokronologi, kombinerad bulk- och enkelkorns analyser såväl som mer statistiska tillvägagångssätt. Resultaten är baserade på tre huvudsakligen studerade artiklar och visar att det är mer troligt att lösskällor kommer från Högalperna och bergsområden, såsom Karpaterna, snarare än från glaciärer, som tidigare varit den mest relevanta idén. -

General Assembly

United Nations A/C.3/71/INF/ 2 Distr.: General General Assembly 25 January 2016 Original: Arabic/Chinese/English/ French/Russian/Spanish ﺃﻋﻀﺎﺀ ﺍﻟﻠﺠﻨﺔ 第三委员会成员 Membership of the Third Committee Membres de la Troisième Commission Члены Третьего комитета Miembros de la Tercera Comisión ﻣﻠﺤﻮﻇﺔ: ﻳﺮﺟﻰ ﻣﻦ ﺍﻟﻮﻓﻮﺩ ﺍﻟﱵ ﺗﺮﻳﺪ ﺇﺩﺧﺎﻝ ﺃﻳﺔ ﺗﺼﺤﻴﺤﺎﺕ ﻋﻠﻰ ﺍﻟﻘﺎﺋﻤﺔ ﺍﻟﺘ ﺎﻟﻴﺔ ﺃﻥ ﺗﺮﺳﻠﻬﺎ، ﻛﺘﺎﺑﺔ، ﺇﱃ ﺃﻣﲔ ﺍﻟﻠﺠﻨﺔ، ﺍﻟﻐﺮﻓﺔ ﺭﻗﻢ S-1279 ، ﻣﺒﲎ Secretariat Building 注意:请各代表团把对以下名单的更正用书面送交 Secretariat Building 大楼 S-1279 室委员会秘书。 Note : Delegations are requested to send their corrections to the following list in writing to the Secretary of the Committee, room S-1279, Secretariat Building. Note: Les délégations sont priées d’envoyer leurs corrections à la présente liste, par écrit, au Secrétaire de la Commission, bureau S-1279, Secretariat Building. Примечание: Делегациям предлагается послать свои исправелния к настоящему списку в письменной форме секретарю Комитета, комната S-1279, здание Secretariat Building. Nota: Se ruega a las delegaciones se sirvan enviar sus correcciones a la siguiente lista, por escrito, a la Secretaria de la Comisión, oficina S-1279, Secretariat Building. ﺍﻟﺮﺋﻴﺲ 主席 Chairman Président Председатель Presidente ﻧﻮﺍﺏ ﺍﻟﺮﺋﻴﺲ (H.E. Mrs. María Emma Mejía (Colombia 副主席 Vice-Chairmen Vice-Présidents Заместители Председателя Vicepresidentes Mr. Masni Eriza (Indonesia) Mrs. Karina Węgrzynowska (Poland) Mr. Andreas Glossner (Germany) ﺍﳌﻘﺮﺭ 报告员 Rapporteur Докладчик Relator Mrs. Cecile Mbala Eyenga (Cameroon) 270117 270117 17-01287 (M) 1701287 A/C.3/71/INF/2 成员 /Members/Membres/Члены/Miembros/ ﺍﻷﻋﻀﺎﺀ ﺍﳌﺴﺘﺸﺎﺭﻭﻥ ﺍﳌﻤﺜﻠﻮﻥ ﺍﳌﻨﺎﻭﺑﻮﻥ ﺍﳌﻤﺜﻞ ﺍﻟﺒﻠﺪ 国家 代表 候补代表 顾问 Country Representative Alternates Advisers Pays Représentant Suppléants Conseillers Страна Представитель Заместители Советники País Representante Suplentes Consejeros Afghanistan Mr. -

"The Lost Cyclist" Non-Partisan Website Devoted to Armenian Affairs, Human Rights and Democracy

Keghart "The Lost Cyclist" Non-partisan Website Devoted to Armenian Affairs, Human Rights https://keghart.org/the-lost-cyclist/ and Democracy "THE LOST CYCLIST" Posted on August 29, 2010 by Keghart Category: Opinions Page: 1 Keghart "The Lost Cyclist" Non-partisan Website Devoted to Armenian Affairs, Human Rights https://keghart.org/the-lost-cyclist/ and Democracy By Mark Gavoor, Glenview IL, 31 August 2010 On July 15th, I received an email from The Chainlink which is “a Chicago online bicycling community.” I am a member and an avid cyclist. For some reason, I paid a little more attention to this e-mail than most I receive from them and actually read it. Amongst the newsy tidbits in the email was an announcement for a meet the author and book reading the next evening, Friday, July 16th. The tidbit read: David Herlihy, author of "Bicycle: The History" will be presenting his newest two-wheeled tome, "The Lost Cyclist: The Epic Tale of an American Adventurer and His Mysterious Disappearance" in Lincoln Square. By Mark Gavoor, Glenview IL, 31 August 2010 On July 15th, I received an email from The Chainlink which is “a Chicago online bicycling community.” I am a member and an avid cyclist. For some reason, I paid a little more attention to this e-mail than most I receive from them and actually read it. Amongst the newsy tidbits in the email was an announcement for a meet the author and book reading the next evening, Friday, July 16th. The tidbit read: David Herlihy, author of "Bicycle: The History" will be presenting his newest two-wheeled tome, "The Lost Cyclist: The Epic Tale of an American Adventurer and His Mysterious Disappearance" in Lincoln Square. -

STAFF and STUDENTS Phd Thesis, Entitled 'Colonial Copyright and the Photographic Ongratulations to Eriko Image: Canada in the Frame', On

Monthly Newsletter January & February 2011 Royal Holloway, University of London Number 199 STAFF AND STUDENTS PhD Thesis, entitled 'Colonial Copyright and the Photographic ongratulations to Eriko Image: Canada in the Frame', on Yasue who successfully 25 February. His examiners were Prof James Ryan (Exeter) and Prof C discussed her PhD entitled Richard Dennis (UCL). Philip's “The Practice and the Reproduction of Tourist thesis was funded by the ESRC Landscapes in Contemporary under a CASE studentship in CQR Lecture – Mark Japan”. The two external which the British Library was the Hardiman, RHUL „Extending the examiners were Tim Edensor collaborative partner. The Tephrochronological Framework (Manchester Metropolitan) and supervisors were Felix Driver and Across Southern Europe During Paul Waley (University of Leeds) Carole Holden (at the British the Last Glacial; The Potential for who approved the thesis subject Library), and the advisor was Synchronizing Palaeo-Records‟ – only to minor corrections. David Lambert. Philip is now 17th March at 5pm, Room 170 Claudio Minca was her supervisor employed as a Curator of and her advisor was Phil Crang. Canadian and Caribbean Learning From Egypt (Special Collections at the British Library. Workshop on the „Arab Spring‟) – Congratulations to Rong Zheng Jessica Jacobs, RHUL. Monday who was awarded her PhD subject Congratulations to Charles Howie 21st March at 12 noon, Room Q170 to minor corrections yesterday. who has been awarded his PhD. Tracy's thesis title was „Producing His revised thesis, entitled End of Term – Friday, 25th March the Water Conservation Subject in “Cooperation and contestation: 2011 China's Urban Areas: Public farmer-state relations in Service Messages, Household agricultural transformation, An Start of Summer Term – Tuesday, Dynamics and Geographies of Giang Province, Vietnam”, has 26th April 2011 Adoption‟. -

MODELING of the ARAL and CASPIAN SEAS DRYING out INFLUENCE to CLIMATE and ENVIRONMENTAL CHANGES Slobodan B

Acta geographica Slovenica, 54-1, 2014, 143–161 MODELING OF THE ARAL AND CASPIAN SEAS DRYING OUT INFLUENCE TO CLIMATE AND ENVIRONMENTAL CHANGES Slobodan B. Markovi}, Albert Ruman, Milivoj B. Gavrilov, Thomas Stevens, Matija Zorn, Bla` Komac, Drago Perko The Caspian sea (Credit: NASA). Modelling of the Aral and Caspian seas drying out influence to climate and environmental changes Modelling of the Aral and Caspian seas drying out influence to climate and environmental changes DOI: http: //dx.doi.org/10.3986/AGS54304 UDC: 911.2:551.588(5 -191.2) COBISS: 1.01 ABSTRACT: The complete drying out of the Aral and Caspian seas, as isolated continental water bodies, and their potential impact on the climate and environment is examined with numerical simulations. Simulations use the atmospheric general circulation model (ECHAM5) as well as the hydrological discharge (HD) model of the Max -Planck -Institut für Meteorologie . The dry out is represented by replacing the water surfaces in both of the seas with land surfaces. New land surface elevation is lower, but not lover than 50 m from the present mean sea level. Other parameters in the model remain unchanged. The initial meteoro - logical data is real; starting with January 1, 1989 and lasting until December 31, 1991. The final results were analyzed only for the second, as the first year of simulation was used for the model spinning up . The drying out of both seas leads to an increase in land surface and average monthly air temperature dur - ing the summer, and a decrease of land surface and average monthly air temperature during the winter, above the Caspian Sea.