FTBG Newsletter May 2013

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Veronika Nývltová

Univerzita Palackého v Olomouci Přírodov ědecká fakulta Bakalá řská práce Olomouc 2010 Veronika Nývltová Univerzita Palackého v Olomouci Přírodov ědecká fakulta Katedra botaniky Charakteristika skupiny vrby bobkolisté ( Salix phylicifolia agg.) ve St řední Evrop ě s důrazem na Salix bicolor v Česku. Bakalá řská práce Studijní program: Biologie Studijní obor: Systematická biologie a ekologie Forma studia: Prezen ční Autor: Veronika Nývltová Vedoucí práce: RNDr. Radim J. Vašut, Ph.D. Konzultant práce: Mgr. Martin Dan čák, Ph.D. Olomouc 2010 2 Prohlášení: Prohlašuji, že jsem p ředloženou bakalá řskou práci vypracovala samostatn ě pod vedením RNDr. Radima J. Vašuta Ph.D. Uvedla jsem veškerou literaturu, ze které jsem čerpala. V Olomouci dne 12. 8. 2010 Podpis: 3 Pod ěkování: Ráda bych pod ěkovala svému školiteli Radimovi J. Vašutovi za trp ělivost a ochotu. Dále děkuji Michalovi Hronešovi za pomoc p ři terénním pr ůzkumu. 4 Bibliografická identifikace Jméno a p říjmení autora: Veronika Nývltová Název práce: Charakteristika skupiny vrby bobkolisté ( Salix phylicifolia agg.) ve St řední Evrop ě s důrazem na Salix bicolor v Česku Typ práce: bakalá řská práce Pracovišt ě: Katedra botaniky, P řírodov ědecká fakulta UP Vedoucí práce: RNDr. Radim J. Vašut Ph.D. Rok obhajoby práce: 2010 Abstrakt: Vrby ( Salix spp.) pat ří k taxonomicky zna čně problematickým skupinám rostlin, ale práv ě tím jsou zajímavé a poskytují v tomto sm ěru stále nové objevy. V naší kv ěten ě náleží vysokohorské druhy vrb mezi vzácné taxony. Jedním z důvod ů jejich vzácnosti je v mnoha p řípadech reliktní charakter druh ů. Takovým p říkladem je i vrba dvoubarvá ( Salix bicolor ), jíž se v ěnuje p ředložená práce. -

Biodiversity and Ecology of Critically Endangered, Rûens Silcrete Renosterveld in the Buffeljagsrivier Area, Swellendam

Biodiversity and Ecology of Critically Endangered, Rûens Silcrete Renosterveld in the Buffeljagsrivier area, Swellendam by Johannes Philippus Groenewald Thesis presented in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Masters in Science in Conservation Ecology in the Faculty of AgriSciences at Stellenbosch University Supervisor: Prof. Michael J. Samways Co-supervisor: Dr. Ruan Veldtman December 2014 Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za Declaration I hereby declare that the work contained in this thesis, for the degree of Master of Science in Conservation Ecology, is my own work that have not been previously published in full or in part at any other University. All work that are not my own, are acknowledge in the thesis. ___________________ Date: ____________ Groenewald J.P. Copyright © 2014 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved ii Stellenbosch University http://scholar.sun.ac.za Acknowledgements Firstly I want to thank my supervisor Prof. M. J. Samways for his guidance and patience through the years and my co-supervisor Dr. R. Veldtman for his help the past few years. This project would not have been possible without the help of Prof. H. Geertsema, who helped me with the identification of the Lepidoptera and other insect caught in the study area. Also want to thank Dr. K. Oberlander for the help with the identification of the Oxalis species found in the study area and Flora Cameron from CREW with the identification of some of the special plants growing in the area. I further express my gratitude to Dr. Odette Curtis from the Overberg Renosterveld Project, who helped with the identification of the rare species found in the study area as well as information about grazing and burning of Renosterveld. -

Acer Buergerianum Plants, Adequately Moist in Summer but Well Drained in Winter Is "Trident Maple" a Pretty Small Tree Whose Grace Is Enhanced by the Key to Success

Acer buergerianum plants, adequately moist in summer but well drained in winter is "Trident Maple" A pretty small tree whose grace is enhanced by the key to success. 3m. the small three-lobed leaves. Particularly good autumn colour begins scarlet turning orange-yellow. A good hardy Maple Acer x conspicuum 'Silver Cardinal' tolerant of many less favoured sites. 4m. This Snakebark has the most incredible pink and cream variegated foliage, highlighted by the red petioles and young stems. It Acer circinatum 'Monroe' occurred as a chance seedling of A. pensylvanicum and received A plant I've lusted after for years! Shrubby habit, with deeply an Award of Merit in 1985. Our stock is directly derived from incised light green leaves (even more so than A. japonicum the original seedling in the Windsor Great Park. Unless your soil 'Aconitifolium'). Predominantly yellow autumn colours may is very good, it is safest in dappled shade. 3m. develop some orange. Worthy of a special site. 3m. Acer x conspicuum 'Silver Vein' Acer circinatum 'Pacific Fire' A hybrid between A. davidii George Forrest and A. Imagine the coral bark colour of Acer palmatum 'Sangokaku' pensylvanicum Erythrocladum found at Hilliers about 1960. It is combined with the larger leaves and more tolerant growth arguably the best of the basic snakebarks for garden suitability requirements of this species, and the result is a plant with and good colour with its rich purple and white striped winter awesome potential. Fantastic autumn colour too. bark, becoming green with maturity. 5m. Acer circinatum 'Sunglow' Acer davidii This has been on my "wanted" list ever since I first saw it Delightful small tree noted for dazzling autumn colour and photographed! Apricot coloured young growth matures to attractive white striped purple bark in winter. -

Green Spaces Brochure

Black Environment Network Ethnic Communities and Green Spaces Guidance for green space managers Green Space Location Type of space Theme Focus Use Improve Create 1 Abbeyfield Park Sheffield Urban park Multi-cultural festival in the park Park dept promoting use by ethnic communities / 2 Abney Park Cemetery London Local Nature Reserve Ecology, architecture and recreation Biodiversity awareness raising in mixed use space / 3 Al Hilal Manchester Community centre garden Improving the built environment Cultural and religious identity embodied in design / 4 Calthorpe Project London Multi-use green space Multi-functional inner city project Good design brings harmony among diverse users / 5 Cashel Forest Sterling Woodland (mixed) Commemorative forest of near-native ecology Refugee volunteers plant /tend commemorative trees / 6 Chelsea Physic Garden S. London Botanic garden Medicinal plants from around the world Pleasure visit/study facility with cultural links / 7 Chinese Hillside RBGE Edinburgh Botanic garden Simulated Chinese ecological landscape Living collection/ecological experiment / 8 Chumleigh Gardens S. London Multicultural gardens Park gardens recognising local ethnic presence Public park created garden reflecting different cultures / 9 Clovelly Centre Southampton Community centre garden Outdoor recreation space for older people Culturally sensitive garden design / 10 Concrete to Coriander Birmingham Community garden Expansion of park activities for food growing Safe access to land for Asian women / 11 Confused Spaces Birmingham Incidental -

June 2019 Monthly Report

June 2019 Monthly Report The June monthly report makes for a lot of interesting reading with many activities taking place that kept the Rangers on their toes. The report provides the usual monthly compliance statistics including the discovery of snares, followed by a report back on the Voortrekkers annual visit, activities surround alien plant control and fuel load reduction, maintenance and some interesting wildlife highlights from the month. This report then details an alien biomass expo the Rangers attended, the very intriguing washout of a rare beaked whale and the Conservancy’s involvement therein, a conversation piece on Haworthia conservation and the release of a lesser Flamingo. The report is then concluded with the Capped Wheatear which features as this month’s monthly species profile. Plough snails enjoying their jellyfish feast. ‘If we knew how many species we’ve already eradicated, we might be more motivated to protect those that still survive. This is especially relevant to the large animals of the oceans.’ – Yuval Noah Harari 2 JUNE 2019 Compliance Management Marine Living Resources Act During June, a total of 24 recreational fishing, spearfishing and bait collecting permits were checked by Taylor, Kei and Daniel. Of the 24 permits checked, 6 people (25%) failed to produce a valid permit and were issued a verbal warning. Snares On the 3rd of June the Rangers came across some very rudimentary snares whilst checking some of the woodcutting operations on Fransmanshoek. Old packing strapping was used to create snares and were found tied to the base of bushes with a simple noose knot made at the other end. -

The Rare Plant Register of South Northumberland (VC67) 2010 Quentin J

The Rare Plant Register of South Northumberland (VC67) 2010 Quentin J. Groom and A. John Richards Introduction The Vice-County Rare Plant Registers are an initiative of the Botanical Society of the British Isles to summarise the status of rare and conservation-worthy plants in each vice-county. The intention is to create an up-to-date summary of the sites of rare plants and their status at these sites. Rare Plant Registers intend to identify gaps in our knowledge, aid conservation efforts and encourage monitoring of our rare plants. Criteria for Inclusion The guidelines of the BSBI were followed in the production of this Rare Plant Register. All native vascular plants with a national status of “rare” (found in 1-15 hectads in Britain) or “scarce” (found in 16-100 hectads in Britain) are included even if that species is not native to South Northumberland. In addition, all native species locally rare or scarce in South Northumberland are included, as are extinct native species. These guidelines were occasionally relaxed to include some local specialities and hybrids of note. We would have liked to restrict the list to current sites for each species. However, in many cases, there is too little up-to-date information to make this possible. The listed sites are those where the species might still exist or has existed recently. In most cases, a site is included if a species has been recorded there since 1970. Sites without detailed locality information or of dubious provenance are not included. Where possible, we have tried to show the known history of a site by noting the date of first and last record. -

Download PCN-Acer-2017-Holdings.Pdf

PLANT COLLECTIONS NETWORK MULTI-INSTITUTIONAL ACER LIST 02/13/18 Institutional NameAccession no.Provenance* Quan Collection Id Loc.** Vouchered Plant Source Acer acuminatum Wall. ex D. Don MORRIS Acer acuminatum 1994-009 W 2 H&M 1822 1 No Quarryhill BG, Glen Ellen, CA QUARRYHILL Acer acuminatum 1993.039 W 4 H&M1822 1 Yes Acer acuminatum 1993.039 W 1 H&M1822 1 Yes Acer acuminatum 1993.039 W 1 H&M1822 1 Yes Acer acuminatum 1993.039 W 1 H&M1822 1 Yes Acer acuminatum 1993.076 W 2 H&M1858 1 No Acer acuminatum 1993.076 W 1 H&M1858 1 No Acer acuminatum 1993.139 W 1 H&M1921 1 No Acer acuminatum 1993.139 W 1 H&M1921 1 No UBCBG Acer acuminatum 1994-0490 W 1 HM.1858 0 Unk Sichuan Exp., Kew BG, Howick Arb., Quarry Hill ... Acer acuminatum 1994-0490 W 1 HM.1858 0 Unk Sichuan Exp., Kew BG, Howick Arb., Quarry Hill ... Acer acuminatum 1994-0490 W 1 HM.1858 0 Unk Sichuan Exp., Kew BG, Howick Arb., Quarry Hill ... UWBG Acer acuminatum 180-59 G 1 1 Yes National BG, Glasnevin Total of taxon 18 Acer albopurpurascens Hayata IUCN Red List Status: DD ATLANTA Acer albopurpurascens 20164176 G 1 2 No Crug Farm Nursery QUARRYHILL Acer albopurpurascens 2003.088 U 1 1 No Total of taxon 2 Acer amplum (Gee selection) DAWES Acer amplum (Gee selection) D2014-0117 G 1 1 No Gee Farms, Stockbridge, MI 49285 Total of taxon 1 Acer amplum 'Gold Coin' DAWES Acer amplum 'Gold Coin' D2015-0013 G 1 2 No Gee Farms, Stockbridge, MI 49285, USA Acer amplum 'Gold Coin' D2017-0075 G 2 2 No Shinn, Edward T., Wall Township, NJ 07719-9128 Total of taxon 3 Acer argutum Maxim. -

Society News, Etc

HORTICULTURAL SHOWS & OTHER EVENTS URBAN FERNS AROUND MANCHESTER MUSEUM – 28 July Dave Bishop On the last Saturday in July, BPS Secretary Yvonne Golding gave a presentation on Urban Ferns to members of the public and three BPS members at Manchester Museum. Around 15 people attended. Yvonne first gave an introduction to the BPS from its formation in 1891 to the current day. Following on from this we saw an excellent video The Secret Life of Ferns, which explains the complicated fern life-cycle in a simple and understandable way. We then put this knowledge into practice when we were shown how to grow ferns from spores and we were able to examine a selection of living prothalli, which many people present had never seen before. After tea we saw a slide-show of ferns in urban environments, including some exotic species living in a London basement (courtesy of John Edgington), native species living in Oxford drains (Nick Hards), York downpipes (Alison and Liz Evans), Sheffield cemeteries, the back streets of Scarborough, Manchester walls and Edinburgh men’s toilets. After the show we went on a short walk around the Museum, finding ferns growing on walls, in drains and gutters, along downpipes and even on an old extractor fan. We soon found eight species: Asplenium ruta-muraria, A. scolopendrium, A. trichomanes, Athyrium filix-femina, Dryopteris dilatata, D. filix-mas, Polypodium vulgare and not forgetting Equisetum arvense. Yvonne and I then went to the pub as it was my birthday! Having seen John Edgington’s photo of forked spleenwort in London, I’ve been scouring the streets of Manchester in search of equally exciting ferns. -

Biological Control of Cape Ivy Project 2004 Annual

Biological Control of Cape ivy Project 2004 Annual Research Report prepared by Joe Balciunas, Chris Mehelis, and Maxwell Chau, with contributions from Liamé van der Westhuizen and Stefan Neser Flowering Cape ivy overgrowing trees and native vegetation along California’s coast near Bolinas United States Department of Agriculture - Agricultural Research Service Western Regional Research Center - Exotic & Invasive Weed Research Unit 800 Buchanan St., Albany, California 94710 (510) 559-5975 FAX: (510) 559-5982 Executive Summary by Dr. Joe Balciunas This is our first attempt at an ‘electronic’ report, and most of you will receive our Annual Report for 2004 as PDF attachment to an email. We hope that this will make our report more easily accessible, since you may chose to store it on your hard disk. We made solid progress during 2004 towards our goal of completing our host range testing of our two most promising potential biological control agents for Cape ivy. We overcame a summertime ‘crash’ of our laboratory colonies, and by year’s end had strong colonies of both the gall fly, Parafreutreta regalis, and the stem-boring moth, Digitivalva delaireae. By the end of 2004, we had tested more than 80 species of plants, and neither of our candidate agents was able to complete development on anything other than their Cape ivy host. The single dark cloud has been the continuing downturn in external funds to support our Cape ivy research, especially that conducted by our cooperators in Pretoria, South Africa. While we have managed to maintain a small research effort there, our cooperators are no longer assisting us in our host range evaluations. -

Plastome Structure and Phylogenetic Relationships of Styracaceae (Ericales)

Plastome Structure and Phylogenetic Relationships of Styracaceae (Ericales) Xiu-lian Cai Hainan University Jacob B. Landis Cornell University Hong-Xin Wang Hainan University Jian-Hua Wang Hainan University Zhi-Xin Zhu Hainan University Huafeng Wang ( [email protected] ) Hainan University https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0218-1728 Review Keywords: Styracaceae, Plastome, Genome structure, Phylogeny, positive selection Posted Date: January 29th, 2021 DOI: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-55283/v2 License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Read Full License Page 1/25 Abstract Background: The Styracaceae are a woody, dicotyledonous family containing 12 genera and an estimated 160 species. Recent studies have shown that Styrax and Sinojackia are monophyletic, Alniphyllum and Bruinsmia cluster into a clade with an approximately 20-kb inversion in the Large Single-Copy (LSC) region. Halesia and Pterostyrax are not supported as monophyletic, while Melliodendron and Changiostyrax always form sister clades . Perkinsiodendron and Changiostyrax were newly established genera of Styracaceae. However, the phylogenetic relationship of Styracaceae at the genera level needs further research. Results: We collected 28 complete plastomes of Styracaceae, including 12 sequences newly reported here and 16 publicly available complete plastome sequences, comprising 11 of the 12 genera of Styracaceae. All species possessed the typical quadripartite structure of angiosperm plastomes, and the sequence difference is small, except for the large 20-kb (14 genes) inversion region found in Alniphyllum and Bruinsmia. Seven coding sequences (rps4, rpl23, accD, rpoC1, psaA, rpoA and ndhH) were identied to possess positively selected sites. Phylogenetic reconstructions based on seven data sets (i.e., LSC, SSC, IR, Coding, Non-coding, combination of LSC+SSC and concatenation of LSC+SSC+one IR) produced similar topologies. -

PLANTS of PEEBLESSHIRE (Vice-County 78)

PLANTS OF PEEBLESSHIRE (Vice-county 78) A CHECKLIST OF FLOWERING PLANTS AND FERNS David J McCosh 2012 Cover photograph: Sedum villosum, FJ Roberts Cover design: L Cranmer Copyright DJ McCosh Privately published DJ McCosh Holt Norfolk 2012 2 Neidpath Castle Its rocks and grassland are home to scarce plants 3 4 Contents Introduction 1 History of Plant Recording 1 Geographical Scope and Physical Features 2 Characteristics of the Flora 3 Sources referred to 5 Conventions, Initials and Abbreviations 6 Plant List 9 Index of Genera 101 5 Peeblesshire (v-c 78), showing main geographical features 6 Introduction This book summarises current knowledge about the distribution of wild flowers in Peeblesshire. It is largely the fruit of many pleasant hours of botanising by the author and a few others and as such reflects their particular interests. History of Plant Recording Peeblesshire is thinly populated and has had few resident botanists to record its flora. Also its upland terrain held little in the way of dramatic features or geology to attract outside botanists. Consequently the first list of the county’s flora with any pretension to completeness only became available in 1925 with the publication of the History of Peeblesshire (Eds, JW Buchan and H Paton). For this FRS Balfour and AB Jackson provided a chapter on the county’s flora which included a list of all the species known to occur. The first records were made by Dr A Pennecuik in 1715. He gave localities for 30 species and listed 8 others, most of which are still to be found. Thereafter for some 140 years the only evidence of interest is a few specimens in the national herbaria and scattered records in Lightfoot (1778), Watson (1837) and The New Statistical Account (1834-45). -

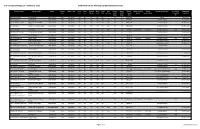

Tree Canopy Coverage List - Deciduous Trees Snohomish County Planning and Development Services

Tree Canopy Coverage List - Deciduous Trees Snohomish County Planning and Development Services Scientific Name Common Name Family Growth Species Type Street Native Drought Moist Utility Root Mature Mature Mature Annual Growth Annual Average Growth Rate Est 20 year Longevity (if Type Tree Tree Tolerant Soil Safe Damage Height Width Canopy Height Growth Width Canopy (sq available) (feet) (feet) Area ft) Abelia grandiflora Glossy Abelia Caprifoliaceae Shrub Deciduous No No No No No 6 6 28.27431 Rapid Moderate Acer campestre Hedge Maple Sapindaceae Tree Deciduous Yes No No No Yes Low 35 25 490.87344 12 inches/season 40-150 years Acer campestre 'Evelyn' Queen Elizabeth Hedge Sapindaceae Tree Deciduous Yes No No Yes No Low 50 25 490.87344 12 inches/season 40-150 years Maple Acer capillipes Japanese snakebark Maple Sapindaceae Tree Deciduous No No No Yes No Low 35 35 962.11194 24 inches/season 40-150 years Acer circinatum Vine Maple Sapindaceae Both Deciduous No Yes No Yes No Low 25 20 314.159 12-24 inches 12 inches 24 inches/season 240 40-150 years Acer fremanii 'Scarsen' Scarlet Sentinel Maple Sapindaceae Tree Deciduous Yes No Yes Yes No 40 20 314.159 24 inches/season 50-150 years Acer griseum Paperbark Maple Sapindaceae Tree Deciduous Yes No No Yes Yes Low 25 15 176.71444 12-24 inches/season 40-150 years Acer macrophyllum Bigleaf Maple Sapindaceae Tree Deciduous No Yes Yes Yes No 75 30 706.85775 36 inches 24 inches 36 inches/season 480 >150 years Acer nigrum Greencolumn Maple Sapindaceae Tree Deciduous Yes No No No No 50 20 314.159 12-24 inches/season