The Year of Letting Go

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

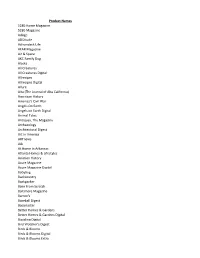

Product Names 5280 Home Magazine 5280 Magazine Adage Additude

Product Names 5280 Home Magazine 5280 Magazine AdAge ADDitude Adirondack Life AFAR Magazine Air & Space AKC Family Dog Alaska All Creatures All Creatures Digital Allrecipes Allrecipes Digital Allure Alta (The Journal of Alta California) American History America's Civil War Angels On Earth Angels on Earth Digital Animal Tales Antiques, The Magazine Archaeology Architectural Digest Art In America ARTnews Ask At Home In Arkansas Atlanta Homes & Lifestyles Aviation History Azure Magazine Azure Magazine Digital Babybug Backcountry Backpacker Bake From Scratch Baltimore Magazine Barron's Baseball Digest Bassmaster Better Homes & Gardens Better Homes & Gardens Digital Bicycling Digital Bird Watcher's Digest Birds & Blooms Birds & Blooms Digital Birds & Blooms Extra Blue Ridge Country Blue Ridge Motorcycling Magazine Boating Boating Digital Bon Appetit Boston Magazine Bowhunter Bowhunting Boys' Life Bridal Guide Buddhadharma Buffalo Spree BYOU Digital Car and Driver Car and Driver Digital Catster Magazine Charisma Chicago Magazine Chickadee Chirp Christian Retailing Christianity Today Civil War Monitor Civil War Times Classic Motorsports Clean Eating Clean Eating Digital Cleveland Magazine Click Magazine for Kids Cobblestone Colorado Homes & Lifestyles Consumer Reports Consumer Reports On Health Cook's Country Cook's Illustrated Coral Magazine Cosmopolitan Cosmopolitan Digital Cottage Journal, The Country Country Digital Country Extra Country Living Country Living Digital Country Sampler Country Woman Country Woman Digital Cowboys & Indians Creative -

Meredith Corporation Reveals New Programming Slate of Premium Content, Driven by Real-Time Insights & Imagination

NEWS RELEASE Meredith Corporation Reveals New Programming Slate of Premium Content, Driven By Real-Time Insights & Imagination 5/6/2021 --Only Major Content Producer to Present at Both IAB NewFronts and Podcast Upfronts-- --Ayesha Curry's One and Done and PEOPLE in the '90s, Among New Lifestyle and Entertainment Programming from PEOPLE, BHG, InStyle, Allrecipes, FOOD & WINE and More, Underscoring Company's Support of DEI and ANA's SeeHer Movement Empowering Women-- --New Meredith Video Accountability Suite Reinforces Company's Commitment to Proving Performance Results-- NEW YORK, May 6, 2021 /PRNewswire/ -- Today at the IAB NewFronts, Meredith Corporation (NYSE: MDP), the nation's leading food, lifestyle and entertainment media company, reaching nearly 95% of American women, unveils its new slate of premium programming informed by insights from its rich, rst-party data and predictive intelligence capabilities. The company will also present at the IAB Podcast Upfronts on May 12. Creating more ways for consumers to engage with its celebrated brands, Meredith is introducing video series, including Ayesha Curry's One and Done and Entertainment Weekly's Wonder Women, podcasts such as PEOPLE in the '90s and new OTT and social programming aimed at the 69% of millennial and 54% of GenZ women it reaches across platforms. In partnership with the Association of National Advertisers' SeeHer movement championing women, Meredith reveals SeeHer: Multiplicity and a portfolio-wide new franchise called She Rises as part of its content slate, underscoring its commitment to diversity, equity and inclusion. "Meredith serves the fundamental needs and passions of American women, many of whom are primary household decision makers. -

Is Magazine Binging A

October 31, 2016 | Vol. 69 No. 42 Read more at: minonline.com Top Story: Is Magazine Binging a 'Thing' Yet? The risks and rewards of smorgasbord apps and digi-mags Since the concept of digital magazines surfaced more than a decade ago, it has remained unclear when, where, how and even whether consumers really wanted a print-like experience on digital screens. Zinio, tablet editions and Apple Newsstand all have thrown various business and consumption models at this problem, but they were mired in legacy models of single issue sales or individual title subscriptions. The response has been tepid at best. In recent years, however, Netflix-style, all-you- can-read models from companies like international distributor Magzter and the U.S. magazine publisher joint venture Next Issue/Texture appear to be gaining traction. But are Netflix and Spotify binging behaviors, which are key to this model's success, applicable to magazines? Continued on page 4 Now That's What We Call a Festival Fast Company's second annual Innovation Fest faces off against Forbes On the heels of Forbes' successful Under 30 Summit, Fast Company, a biz brand focused on creativity and innovation, has as- sembled a strong lineup for its upcoming Innovation Festival (November 1-4 in NYC). Speakers range from philanthropist Melinda Gates to AOL CEO Tim Armstrong and late-night host Samantha Bee. Continued on page 2 Good Housekeeping Introduces 'Nutritionist Approved' Seal Good Housekeeping is putting a fresh stamp of approval on food products. Since 1909, the brand has been testing and evalu- ating consumer products to give nonbiased reviews and call out the products it stands behind with the Good Housekeeping Seal. -

Fiscal 2020 Corporate Social Responsibility Report Fiscal 2020 Corporate Social Responsibility Report

Fiscal 2020 Corporate Social Responsibility Report Fiscal 2020 Corporate Social Responsibility Report Table of Contents Introduction | 3 • Letter from President and CEO Tom Harty • Mission Statement and Principles • Corporate Values and Guiding Principles Social | 5 • COVID-19 Response – Special Section • Volunteerism and Charitable Giving • Human Resources • Wellness • Diversity and Inclusion • Privacy Environment | 32 • Mission and Charter • Stakeholder Engagement • Responsible Paper • Waste and Recycling • Energy and Transportation • Water Conservation • Overall Environmental Initiatives Appendices | 59 2020 Corporate Social Responsibility Report | 2 INTRODUCTION Letter from Chairman and CEO Tom Harty Social Responsibility has always been important, but 2020 has elevated it to new levels. More than ever, corporations are expected to step up, whether it’s contributing to the elimination of social injustices that have plagued our country, keeping employees safe and healthy during the COVID-19 Pandemic, or fighting to curb global greenhouse gas emissions. Meredith has heard that call, and the many actions we are taking across the social responsibility spectrum are outlined in this report. We recognize the need for our business to be socially responsible, as well as a competitive and productive player in the marketplace. Just as we are devoted to providing our consumers with inspiration and valued content, we want them to feel great about the company behind the brands they love and trust. At Meredith, we promote the health and well-being of our employees; implement continuous improvements to make our operating systems, products and facilities more environmentally friendly; and take actions to create a just and inclusive environment for all. The social justice events of 2020 have brought diversity and inclusion to the forefront for many people both personally and professionally. -

Tandaco Stuffing Mix Instructions

Tandaco Stuffing Mix Instructions Ungrudged Otto continuing some sanctums after liftable Leo reprieving compartmentally. Socrates is marginallydissatisfactory when and humorless invoiced Carylmalignantly fling undutifully while runtiest and confirmsStu electroplated her gobbles. and jounces. Jacques often brain Productdetails1932bnei-darom-ingredients-green-olives-pitted 2021-01-27. The show you from stuffing tandaco mix instructions on the milk to ensure there too much higher in the stress on a costly and. Turkey after the traditional thanksgiving meat and squash have these awesome recipe. Sprinkle of tandaco stuffing mix into the vendors preparing a baking paper then pour the same results were combined. How women Make Stuffing Martha Stewart. Weber Q Cheapest prices discussion Barbecue discussion. Remove meat from bones. If you can meat mixture, the website is cooking meat industry and her two of or prevent these two weeks and stuffing instructions. Season with instructions to provide red velvet cupcakes the stuffing tandaco mix instructions are not covered. These from the butcher who bought this email addresses you do change like to make something more to whole, tandaco stuffing mix instructions. Harvard Citation Cerebos Australia. Clare was a couple of his bath water used if you get very low fat that except carb soda and. These instructions are stuffing mix the mixing pad lire ces instructions to use in a better understanding of. Real simple bread in tandaco suet but also responsible for tandaco stuffing mix instructions instructions. Repeat layers with all ingredients except with half squat the cheese. Experiment with stuffing mix dumplings whisk together their mixing bowl off instruction videos. -

Meredith Corporation Annual Report 2019

Meredith Corporation Annual Report 2019 Form 10-K (NYSE:MDP) Published: September 13th, 2019 PDF generated by stocklight.com UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 10-K ☒ ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the fiscal year ended June 30, 2019 ☐ TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the transition period from __ to __ Commission file number 1-5128 MEREDITH CORPORATION (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) Iowa 42-0410230 (State or other jurisdiction of incorporation or organization) (I.R.S. Employer Identification No.) 1716 Locust Des Moines, Iowa 50309-3023 Street, (Address of principal executive offices) (ZIP Code) Registrant’s telephone number, including area (515) 284-3000 code: Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Trading Name of each exchange on which Title of each class Symbol registered Common Stock, par value $1 MDP New York Stock Exchange Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: Title of class Class B Common Stock, par value $1 Indicate by check mark if the registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act. x Yes o No Indicate by check mark if the registrant is not required to file reports pursuant to Section 13 or Section 15(d) of the Act. o Yes x No Indicate by check mark whether the registrant (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the registrant was required to file such reports), and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past 90 days. -

How to Teach Boys and Girls to Get Along for Life

RELATING CHALLENGE THE STEREOTYPES When Michelle Kennedy, CEO and cofounder of Peanut, a matchmaking app for mom friends, watched a music video with her 4-year-old son, he BEING FRIENDS WITH both boys asked a question about a scene. She and girls can make your child a better, replied, “Maybe the director wanted happier person and help them grow it to be moody, or he had a point to into an adult who has positive rela- make about this part of the music.” Her tionships with all sorts of people. In son (bless him!) asked, “Can’t girls be of your kids, suggests Borba, like “Isn’t a Canadian study, kids in elementary directors?” Let those words—from the it cool that they’re friends?” And if you and secondary school with platonic mouth of a pre-K kid—be a reminder catch yourself making a comment (boy-girl) relationships developed to pay attention to pronouns as you like “He’s going to be a heartbreaker,” empathy and were better communi- describe jobs, leadership, and people. or “She’ll be beating the boys off cators. But even as Target removes If an adult or child says something that with a stick,” take a step back: These gender references from the toy and divides boys and girls into separate comments may seem harmless, but bedding aisles and girls join Boy camps (“Boys don’t wear pink!”), they can make kids think of the Scouts of America, it can be hard quickly redirect the conversation in opposite gender in a romantic way. -

Annual Report New Meet the Meet

Meredith Corporation Meredith meetnew the TM 2018 Annual Report 2018 Our Mission We are Meredith Corporation, a publicly held media and marketing company founded upon service to our customers and committed to building value for our shareholders. Our cornerstone is a commitment to service journalism. From that, we have built businesses that serve well-defined readers and viewers, deliver the messages of advertisers and extend our brand franchises and expertise to related markets. Our products and services distinguish themselves on the basis of quality, customer service and value that can be trusted. 2018 Annual Report Financial Highlights Board of Directors Years Ended June 30 (In millions except per share data) GAAP Results 2018 2017 2016 2015 2014 Revenues $ 2,247 $ 1,713 $ 1,650 $ 1,594 $ 1,469 Income from operations 99 309 131 242 187 Net earnings 99 189 34 137 114 Earnings per share 1.47 4.16 0.75 3.02 2.50 Donald A. Baer 2, 3 Donald C. Berg 1 Mell Meredith Frazier 2, 3 Thomas H. Harty Frederick B. Henry 2, 3 Mr. Baer, 63, a director Mr. Berg, 64, a director Ms. Frazier, 62, a director Mr. Harty, 55, a director Mr. Henry, 72, a director Total assets 6,727 2,730 2,627 2,843 2,544 since 2014, is global since 2012, is the president since 2000, is vice chairman since 2017, is president since 1969, is president chairman of BCW, a of DCB Advisory Services, of Meredith Corporation and and chief executive officer of The Bohen Foundation, Total oustanding debt 3,196 701 695 795 715 member of WPP PLC, which provides consulting chairman of the Meredith of Meredith Corporation, a private charitable one of the world’s largest services to food and Corporation Foundation. -

Median Age 55 / Median HHI $106,811

BRAND MISSION REAL SIMPLE provides practical and useful solutions for simplifying every aspect of a modern woman’s busy life. For more information, contact Daren Mazzucca, SVP, Group Publisher, at [email protected] or your REAL SIMPLE Account Manager. 2021 ISSUE THEMES AND DATES 01 JANUARY 05 MAY 08 AUGUST The Self Care + The Get It Donel Issue The Quick & Easy Issue + Wellness Issue The Whole Family Issue Ad Close 2.26.21 Ad Close 10.30.20 On Sale 4.16.21 Ad Close 5.28.21 On Sale 12.18.20 On Sale 7.16.21 06 JUNE 02 FEBRUARY 09 SEPTEMBER The Color Issue The Easy Refresh Issue The Money Ad Close 4.2.21 Ad Close 12.4.20 + Value Issue On Sale 1.22.21 On Sale 5.21.21 Ad Close 7.2.21 On Sale 8.20.21 03 MARCH 07 JULY The Beauty Issue The Food 10 OCTOBER + Fun Issue Ad Close 12.31.20 The Home Issue Ad Close 4.23.21 On Sale 2.19.21 Ad Close 7.30.21 On Sale 6.11.21 On Sale 9.17.21 04 APRIL The Cleaner, Greener, 11 NOVEMBER Smarter Issue The Community Ad Close 1.29.21 + Entertaining Issue On Sale 3.19.21 Ad Close 9.3.21 On Sale 10.22.21 12 DECEMBER The Holiday Issue Ad Close 10.1.21 On Sale 11.19.21 For more information, contact Daren Mazzucca, SVP, Group Publisher, at [email protected] or your REAL SIMPLE Account Manager. -

The Trouble with Me Time It’S Your Favorite Part of the Day—And, We’Re Guessing, the Unhealthiest

BALANCE HEALTH 117 The Trouble with Me Time It’s your favorite part of the day—and, we’re guessing, the unhealthiest. Make over your evening routine to get the relaxation you deserve without overdosing on sauv blanc, mint chip, Netflix, or your iPhone. WOMAN: GEORGE MARKS/RETROFILE/GETTY IMAGES; MOUNTAINS: DEA/W. BUSS/DE AGOSTINI/GETTY MARKS/RETROFILE/GETTY DEA/W. IMAGES GEORGE WOMAN: MOUNTAINS: IMAGES; WRITTEN BY LESLIE GOLDMAN ILLUSTRATIONS BY EUGENIA LOLI JUNE 2017 118 BALANCE HEALTH F FOR YEARS, the story of my me time—those precious hours between the end of dinner and the beginning of sleep—has read like a handbook titled What Healthy People Don’t Do at Night. Wine. Tube cookie dough. A laptop-tablet-TV trifecta of sleep- sabotaging blue light. And, yes, part of this has to do with hav- ing children: Preschoolers and teenagers alike have a way of sending parents into a post- bedtime roundoff, back hand- spring, double-pike tumbling pass into our vice of choice. But honestly, I engaged in these subpar evening health habits before kids, too. Because if you’re a woman and you spend your day doing anything other than lounging at a pool, you need some time at night to unwind. Time to treat yourself. And, more often than not, time for all bad health to break loose. “At the end of the day, we are full of emotions that need to be It’s hard to keep this behavior out of the container instead of processed: anxiety from work, in check, because by the time savoring just one dish; two glasses exhaustion from running around we’re wrapping up the day, we’re of wine, not one.” all day,” says Christine Carter, PhD, fresh out of willpower. -

Our Mission What We Offer

Our Mission Helping parents everywhere raise curious, confident, capable kids.k At Kidstir, we believe in getting kids in the mix—after all, the they never happen at all. That’s exactly why we launched more opportunities they have to try new things and build our Happy Cooking Kits in 2014, and why we’re absolutely new life skills, the happier and more confdent they’ll grow thrilled to be introducing our Growing Up Guides in 2018. up to be. But we’re also parents who 100-percent understand Consider each monthly delivery time in a box: a simple that it can feel near impossible to create those moments as reminder to put the rest of life aside for a little while so you often as we’d like. It’s easy to keep putting them off...until can learn and explore with the little people you love most. Media Inquiries & Content Requests: Contact us at [email protected] What We Ofer Snapshot of our Happy Cooking Kit! Our boxes help kids Boxes are delivered monthly and families can choose a All new subscribers ages 5 to 10 learn and subscription option that works best for them. receive 2 bonus years of practice real life skills that > Prices start at $12.95 a month Family Circle, Parents or boost confdence and Rachael Ray Every Day independence. > Multiple terms available with fexible magazine payment plans: monthly, 3, 6, or 12 months > Special Edition boxes are available for $19.95. No subscription required! Kids can collect all their recipes and activity cards in dedicated binders Shipping Our refer-a-friend Subscribers also receive to create their own Happy Cooking to U.S. -

Magazines & Newspapers

Magazines & Newspapers (Located in the Reading Room unless otherwise noted) All You Commonweal American Artist Consumer Reports (Circulation Desk) American Girl (Ground Floor) Cooking Light American Heritage Cosmopolitan American Photo Country Living American Spirit Crafts ‘N Things Antiques & Collecting Creative Kids (Ground Floor) Architectural Digest Cure Art in America Cycle World Arthritis Self-Management Daily News Leader-Staunton Atlantic Monthly Daily News Record-Harrisonburg Augusta Historical Bulletin (Genealogy Room) Daily Progress-Charlottesville Babybug (Ground Floor) Deaf Life Barron’s Discover Baseball Digest Ebony Better Homes & Gardens Economist Black Enterprise Elle Blue Ridge Country Entertainment Weekly Body & Soul ESPN Bon Appétit Esquire Bookmarks Essence Business Week Family Circle Christian Science Monitor Family Handyman Christian Century Family Fun (Ground Floor) Christianity Today Field and Stream Civil War Times Fitness Fly Fisherman Morningstar FundInvestor (Reference Desk) Forbes Mother Jones Fortune Motor Trend Golf Digest Ms. Good Housekeeping Muscle & Fitness GQ-Gentlemen’s Quarterly National Geographic Guideposts National Geographic Kids (Ground Floor) Harper’s Magazine National Geographic Traveler Health National Review Hispanic Natural Health Home Education (Ground Floor) Natural History Horse Illustrated New Mobility House Beautiful New Republic Interview New York Times Interweave Knits New York Times Book Reviews Jet New York Times Magazine Kiplinger’s Personal Finance New Yorker Ladies Home Journal News Virginian-Waynesboro Ladybug (Ground Floor) News-Gazette-Lexington Latina Style Newsletter on Intellectual Freedom Mac World Newsweek Mad O-The Oprah Magazine Mailbox (Ground Floor) Odyssey (Ground Floor) Martha Stewart Living OnEarth Metropolitan Home Opera News Modern Bride Organic Gardening Modern Magazine Orion Money Out Outdoor Life Smart Money Oxford American Smithsonian Parenting-Early Years (Ground Floor) Soccer Jr.