FULLTEXT01.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Unity of Heidegger's Project

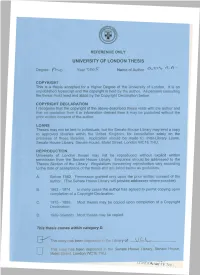

REFERENCE ONLY UNIVERSITY OF LONDON THESIS Degree fV\o Year Too£ Name of Author A-A COPYRIGHT This is a thesis accepted for a Higher Degree of the University of London. It is an unpublished typescript and the copyright is held by the author. All persons consulting the thesis must read and abide by the Copyright Declaration below. COPYRIGHT DECLARATION I recognise that the copyright of the above-described thesis rests with the author and that no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without the prior written consent of the author. LOANS Theses may not be lent to individuals, but the Senate House Library may lend a copy to approved libraries within the United Kingdom, for consultation solely on the premises of those libraries. Application should be made to: Inter-Library Loans, Senate House Library, Senate House, Malet Street, London WC1E 7HU. REPRODUCTION University of London theses may not be reproduced without explicit written permission from the Senate House Library. Enquiries should be addressed to the Theses Section of the Library. Regulations concerning reproduction vary according to the date of acceptance of the thesis and are listed below as guidelines. A. Before 1962. Permission granted only upon the prior written consent of the author. (The Senate House Library will provide addresses where possible). B. 1962- 1974. In many cases the author has agreed to permit copying upon completion of a Copyright Declaration. C. 1975 - 1988. Most theses may be copied upon completion of a Copyright Declaration. D. 1989 onwards. Most theses may be copied. This thesis comes within category D. -

Mind and Social Reality

Masaryk University Faculty of Economics and Administration Study program: Economics METHODOLOGICAL INDIVIDUALISM: MIND AND SOCIAL REALITY Metodologický Individualizmus: Myseľ a Spoločenská Realita Bachelor´s Thesis Advisor: Author: Mgr. Josef Menšík Ph.D. Ján KRCHŇAVÝ Brno 2020 Name and last name of the author: Ján Krchňavý Title of master thesis: Methodological Individualism: Mind and Social Reality Department: Department of Economics Supervisor of bachelor thesis: Mgr. Josef Menšík, Ph.D. Year of defence: 2020 Abstract The submitted bachelor thesis is concerned with the relation between mind and social reality and the role of the mind in the creation of social reality. This relation is examined from the perspective of the social ontology of John Searle, an American philosopher who is considered to be the proponent of methodological individualism. This thesis aims to reconsider the standard, mentalistic interpretation of Searle’s social ontology, one that is centred around the primary role of the mind in the construction of social reality, to examine criticisms of such approach which highlight the professed neglect of the role that social practices have for social reality, and to provide an alternative, practice-based reading of Searle’s social ontology. The thesis thus proceeds first by outlining the standard interpretation of Searle’s theory as put forward mainly in his two monographs on social reality. Subsequently, the objections against such an approach from an alternative, practice-based approach, which highlights the role of social practices for the constitution of society, are raised. Following these objections, the Searle’s social ontology is looked at again in an effort to find an alternative interpretation that would bring it closer to the ideas and principles of the practice-based approach, and thereby provide a response to some objections against the missing role of the social practices in his theory as well as open the way for the novel interpretation of his social ontology. -

How Three Triads Illumine the Authority of the Preached Word

THE WORDS OF THE SPEAKER: HOW THREE TRIADS ILLUMINE THE AUTHORITY OF THE PREACHED WORD By J. D. HERR B.S., Philadelphia Biblical University, 2008 A THESIS Submitted to the faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Theological Studies at Reformed Theological Seminary Charlotte, North Carolina February 2019 Accepted: _______________________________________________________ First Reader, Dr. James Anderson _______________________________________________________ Second Reader !ii ABSTRACT According to J. L. Austin’s important work, How to Do Things With Words, the philosophic and linguistic assumption for centuries has been that saying something “is always and simply to state something.”1 For many people today, speech is simply the description of a place or event. It is either true or false, because it either describes an item or event well, or it does not. It either re-states propositional truth or it does not. Austin’s program was to regain an understanding and awareness of the force of speech—what is done in saying something—and came to be known as speech act theory. Similarly, in the discipline of theology, and in the life of the Church, many people tend to think of preaching as the passing of some “truth” from the divine mind to the human mind, or from the preacher’s mind to the hearer’s mind. While it is that, in a very real and meaningful way, in this paper I seek to explore whether there is more. As incarnate creatures, God has made humans to consist of spiritual and physical aspects. If we focus wholly on the “mental truth transfer” aspect of speech, especially in the case of preaching, how does this leave the Church equipped to bridge the divide between the mental information and what they are to do in their bodies? By interacting with and interfacing the triadic framework of speech act theory with the triadic frameworks of Dorothy Sayers and John Frame, I seek to understand preaching in 1 J. -

Anthropological Theory

Anthropological Theory http://ant.sagepub.com John Searle on a witch hunt: A commentary on John R. Searle's essay ‘Social ontology: Some basic principles’ Richard A. Shweder Anthropological Theory 2006; 6; 89 DOI: 10.1177/1463499606061739 The online version of this article can be found at: http://ant.sagepub.com/cgi/content/abstract/6/1/89 Published by: http://www.sagepublications.com Additional services and information for Anthropological Theory can be found at: Email Alerts: http://ant.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts Subscriptions: http://ant.sagepub.com/subscriptions Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav Downloaded from http://ant.sagepub.com at UNIV OF CHICAGO LIBRARY on November 5, 2007 © 2006 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution. Anthropological Theory Copyright © 2006 SAGE Publications (London, Thousand Oaks, CA and New Delhi) http://ant.sagepub.com Vol 6(1): 89–111 10.1177/1463499606061739 John Searle on a witch hunt A commentary on John R. Searle’s essay ‘Social ontology: Some basic principles’ Richard A. Shweder University of Chicago, USA Abstract In this commentary I respond to John Searle’s conceptual framework for the interpretation of ‘social facts’ as a provocation to spell out some of the philosophical foundations of the romantic pluralist tradition in cultural anthropology. Romantic pluralists in anthropology seek to affirm (to the extent such affirmation is reasonably possible) what the philosopher John Gray describes as ‘the reality, validity and human intelligibility of values and forms of life very different from our own’. With special attention to two examples of contemporary social facts (a witchcraft tribunal in Africa and death pollution practices in a Hindu temple town), the commentary raises questions about John Searle’s approach to the mind-body problem and his account of epistemic objectivity and ontological subjectivity with regard to social facts. -

Reception of Externalized Knowledge a Constructivistic Model Based on Popper's Three Worlds and Searle's Collective Intentionality

Reception of externalized knowledge A constructivistic model based on Popper's Three Worlds and Searle's Collective Intentionality Winfried Gödert – Klaus Lepsky April 2019 Institute of Information Science TH Köln / University of Applied Sciences Claudiusstraße 1, D-50678 Köln [email protected] [email protected] Summary We provide a model for the reception of knowledge from externalized information sources. The model is based on a cognitive understanding of information processing and draws up ideas of an exchange of information in communication processes. Karl Popper's three-world theory with its orientation on falsifiable scientific knowledge is extended by John Searle's concept of collective intentionality. This allows a consistent description of externalization and reception of knowledge including scientific knowledge as well as everyday knowledge. 1 Introduction It is generally assumed that knowledge is in people's minds and that this knowledge can be com- municated to other people as well as taken over by other people. There is also a general consensus that, in addition to direct communication, this can also be achieved by conveying knowledge through various forms of media presentation, e.g. books, and their reception. The prerequisite for this mediation is the externalization of knowledge by the knowledgeable person, e.g. by writing a book.1 For the consideration of such externalization and reception processes it seems reasonable to make the following distinction between types of knowledge: • Knowledge in one's own head for various purposes, such as problem solving or acting. • Knowledge in other people's minds. • Knowledge in externalized form, e.g. -

Being Qua Being

OUP UNCORRECTED PROOF – FIRST-PROOF, 01/06/12, NEWGEN part iv BEING AND BEINGS 114_Shields_Ch14.indd4_Shields_Ch14.indd 334141 11/6/2012/6/2012 66:02:56:02:56 PPMM OUP UNCORRECTED PROOF – FIRST-PROOF, 01/06/12, NEWGEN 114_Shields_Ch14.indd4_Shields_Ch14.indd 334242 11/6/2012/6/2012 66:02:59:02:59 PPMM OUP UNCORRECTED PROOF – FIRST-PROOF, 01/06/12, NEWGEN Chapter 14 BEING QUA BEING Christopher Shields I. Three Problems about the Science of Being qua Being ‘There is a science (epistêmê),’ says Aristotle, ‘which studies being qua being (to on hê(i) on), and the attributes belonging to it in its own right’ (Met. 1003a21–22). This claim, which opens Metaphysics IV 1, is both surprising and unsettling—sur- prising because Aristotle seems elsewhere to deny the existence of any such science and unsettling because his denial seems very plausibly grounded. He claims that each science (epistêmê) studies a unified genus (APo 87a39-b1), but he denies that there is a single genus for all beings (APo 92b14; Top. 121a16, b7–9; cf. Met. 998b22). Evidently, his two claims conspire against the science he announces: if there is no genus of being and every science requires its own genus, then there is no science of being. This seems, moreover, to be precisely the conclusion drawn by Aristotle in his Eudemian Ethics, where he maintains that we should no more look for a gen- eral science of being than we should look for a general science of goodness: ‘Just as being is not something single for the things mentioned [viz. -

Vol. 3 No. 1 January – June, 2014 Page the QUESTION of “BEING”

Vol. 3 No. 1 January – June, 2014 THE QUESTION OF “BEING” IN AFRICAN PHILOSOPHY Lucky U. OGBONNAYA, M.A. Essien Ukpabio Presbyterian Theological College, Itu, Nigeria Abstract This work is of the view that the question of being is not only a problem in Western philosophy but also in African philosophy. It, therefore, posits that being is that which is and has both abstract and concrete aspect. The work arrives at this conclusion by critically analyzing and evaluating the views of some key African philosophers with respect to being. With this, it discovers that the way that these African philosophers have postulated the idea of being is in the same manner like their Western philosophers whom they tried to criticize. This work tries to synthesize the notions of beings of these African philosophers in order to reach at a better understanding of being. This notion of being leans heavily on Asouzu’s ibuanyidanda ontology which does not bifurcate or polarize being, but harmonizes entities or realities that seem to be contrary or opposing in being. KEYWORDS: Being, Ifedi, Ihedi, Force (Vital Force), Missing Link, Muntu, Ntu, Nkedi, Ubuntu, Uwa Introduction African philosophy is a critical and rational explanation of being in African context, and based on African logic. It is in line with this that Jonathan Chimakonam avers that “in African philosophy we study reality of which being is at the center” (2013, 73). William Wallace remarks that “being signifies a concept that has the widest extension and the least comprehension” (1977, 86). It has posed a lot of problems to philosophers who tend to probe into it, its nature and manifestations. -

Having Hands, Even in the Vat: What the Semantic Argument Really Shows About Skepticism by Samuel R Burns

Having Hands, Even in the Vat: What the Semantic Argument Really Shows about Skepticism by Samuel R Burns A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts with Honors Department of Philosophy in The University of Michigan 2010 Advisors: Professor Gordon Belot Assistant Professor David Baker ”With relief, with humiliation, with terror, he understood that he also was an illusion, that someone else was dreaming him.” Jorge Luis Borges, “The Circular Ruins” “With your feet in the air and your head on the ground/Try this trick and spin it/ Your head will collapse/But there’s nothing in it/And you’ll ask yourself: ‘Where is my mind?’” The Pixies © Samuel R Burns 2010 To Nami ii Table of Contents Acknowledgements .............................................................................................................................iv 1. The Foundation ............................................................................................1 1.1. The Causal Theory of Reference ........................................................................4 1.2. Semantic Externalism ........................................................................................11 2. The Semantic Argument ...........................................................................16 2.1. Putnam’s Argument ...........................................................................................16 2.2. The Disquotation Principle ..............................................................................19 -

Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy) Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy the Chinese Room Argument

5/30/2016 The Chinese Room Argument (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy) Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy The Chinese Room Argument First published Fri Mar 19, 2004; substantive revision Wed Apr 9, 2014 The argument and thoughtexperiment now generally known as the Chinese Room Argument was first published in a paper in 1980 by American philosopher John Searle (1932 ). It has become one of the bestknown arguments in recent philosophy. Searle imagines himself alone in a room following a computer program for responding to Chinese characters slipped under the door. Searle understands nothing of Chinese, and yet, by following the program for manipulating symbols and numerals just as a computer does, he produces appropriate strings of Chinese characters that fool those outside into thinking there is a Chinese speaker in the room. The narrow conclusion of the argument is that programming a digital computer may make it appear to understand language but does not produce real understanding. Hence the “Turing Test” is inadequate. Searle argues that the thought experiment underscores the fact that computers merely use syntactic rules to manipulate symbol strings, but have no understanding of meaning or semantics. The broader conclusion of the argument is that the theory that human minds are computerlike computational or information processing systems is refuted. Instead minds must result from biological processes; computers can at best simulate these biological processes. Thus the argument has large implications for semantics, philosophy of language and mind, theories of consciousness, computer science and cognitive science generally. As a result, there have been many critical replies to the argument. -

Social Ontology

Social Ontology Brian Epstein, Tufts University “Social Ontology,” Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, first version published March 2018, http://plato.stanford.edu/social-ontology Social ontology is the study of the nature and properties of the social world. It is concerned with analyzing the various entities in the world that arise from social interaction. A prominent topic in social ontology is the analysis of social groups. Do social groups exist at all? If so, what sorts of entities are they, and how are they created? Is a social group distinct from the collection of people who are its members, and if so, how is it different? What sorts of properties do social groups have? Can they have beliefs or intentions? Can they perform actions? And if so, what does it take for a group to believe, intend, or act? Other entities investigated in social ontology include money, corporations, institutions, property, social classes, races, genders, artifacts, artworks, language, and law. It is difficult to delineate a precise scope for the field (see section 2.1). In general, though, the entities explored in social ontology largely overlap with those that social scientists work on. A good deal of the work in social ontology takes place within the social sciences (see sections 5.1–5.8). Social ontology also addresses more basic questions about the nature of the social world. One set of questions pertains to the constituents, or building blocks, of social things in general. For instance, some theories argue that social entities are built out of the psychological states of individual people, while others argue that they are built out of actions, and yet others that they are built out of practices. -

The Philosophical Development of Gilbert Ryle

THE PHILOSOPHICAL DEVELOPMENT OF GILBERT RYLE A Study of His Published and Unpublished Writings © Charlotte Vrijen 2007 Illustrations front cover: 1) Ryle’s annotations to Wittgenstein’s Tractatus 2) Notes (miscellaneous) from ‘the red box’, Linacre College Library Illustration back cover: Rodin’s Le Penseur RIJKSUNIVERSITEIT GRONINGEN The Philosophical Development of Gilbert Ryle A Study of His Published and Unpublished Writings Proefschrift ter verkrijging van het doctoraat in de Wijsbegeerte aan de Rijksuniversiteit Groningen op gezag van de Rector Magnificus, dr. F. Zwarts, in het openbaar te verdedigen op donderdag 14 juni 2007 om 16.15 uur door Charlotte Vrijen geboren op 11 maart 1978 te Rolde Promotor: Prof. Dr. L.W. Nauta Copromotor: Prof. Dr. M.R.M. ter Hark Beoordelingscommissie: Prof. Dr. D.H.K. Pätzold Prof. Dr. B.F. McGuinness Prof. Dr. J.M. Connelly ISBN: 978-90-367-3049-5 Preface I am indebted to many people for being able to finish this dissertation. First of all I would like to thank my supervisor and promotor Lodi Nauta for his comments on an enormous variety of drafts and for the many stimulating discussions we had throughout the project. He did not limit himself to deeply theoretical discussions but also saved me from grammatical and stylish sloppiness. (He would, for example, have suggested to leave out the ‘enormous’ and ‘many’ above, as well as by far most of the ‘very’’s and ‘greatly’’s in the sentences to come.) After I had already started my new job outside the academic world, Lodi regularly – but always in a pleasant way – reminded me of this other job that still had to be finished. -

Bertrand Russell on Perception and Knowledge (1927 – 59)

BERTRAND RUSSELL ON PERCEPTION AND KNOWLEDGE (1927 – 59) BERTRAND RUSSELL ON PERCEPTION AND KNOWLEDGE (1927 – 59) By DUSTIN Z. OLSON, B.A. (Hons.) A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Philosophy McMaster University © Copyright by Dustin Z. Olson, August 2011 ii MASTER OF PHILOSOPHY (2011) McMaster University (Philosophy) Hamilton, Ontario TITLE: Bertrand Russell on Perception and Knowledge (1927 – 59) AUTHOR: Dustin Z. Olson SUPERVISOR: Nicholas Griffin NUMBER OF PAGES: vii, 154 iii ABSTRACT Bertrand Russell is one of the grandmasters of 20 th Century Analytic Philosophy. It is surprising, then, that his work fell out of fashion later in his career. As a result, very little has been discussed concerning Russell’s work from the period of 1927 – 59. This thesis provides an analysis of Russell’s philosophical work from this era. Our attention here is on Russell’s theory of perception and the underlying metaphysical structure that is developed as a result of his scientific outlook, as Russell’s philosophy during this time focused almost exclusively on perception, knowledge, and the epistemic relationship humans have with the world according to science. And because Russell’s system is in many ways prescient with regards to recent advances made in perception, mind and matter, and knowledge more generally, we also apply his theory to developments in the philosophy of perception since that time. Our initial discussion – Chapters 1 and 2 – is most concerned with an accurate explication of the concepts germane to and conclusions formed from Russell’s theory of perception.