Xerox University Microfilms

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

San José Studies, November 1975

San Jose State University SJSU ScholarWorks San José Studies, 1970s San José Studies 11-1-1975 San José Studies, November 1975 San José State University Foundation Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/sanjosestudies_70s Part of the American Literature Commons, and the Literature in English, North America Commons Recommended Citation San José State University Foundation, "San José Studies, November 1975" (1975). San José Studies, 1970s. 3. https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/sanjosestudies_70s/3 This Journal is brought to you for free and open access by the San José Studies at SJSU ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in San José Studies, 1970s by an authorized administrator of SJSU ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Portrait by Uarnaby Conrad (Courtesy of Steinbeck Research Center) John Steinbeck SAN JOSE STUDIES Volume I, Number 3 November 1975 ARTICLES Warren French 9 The "California Quality" of Steinbeck's Best Fiction Peter Lisca 21 Connery Row and the Too Teh Ching Roy S. Simmonds 29 John Steinbeck, Robert Louis Stevenson, and Edith McGillcuddy Martha Heasley Cox 41 In Search of John Steinbeck: His People and His Land Richard Astro 61 John Steinbeck and the Tragic Miracle of Consciousness Martha Heasley Cox 73 The Conclusion of The Gropes of Wroth: Steinbeck's Conception and Execution Jaclyn Caselli 83 John Steinbeck and the American Patchwork Quilt John Ditsky . 89 The Wayward Bus: Love and Time in America Robert E. Work 103 Steinbeck and the Spartan Doily INTERVIEWS Webster F. Street 109 Remembering John Steinbeck Adrian H. Goldstone 129 Book Collecting and Steinbeck BOOK REVIEWS Robert DeMott 136 Nelson Valjean. -

Steinbeck John: Red Pony Pdf, Epub, Ebook

STEINBECK JOHN: RED PONY PDF, EPUB, EBOOK John Steinbeck | 100 pages | 01 Feb 1993 | Penguin Books Ltd | 9780140177367 | English | United States Steinbeck John: Red Pony PDF Book I would not have liked farm life, unless we were just raising food crops. Unable to reach the horse in time, he arrives while a buzzard is eating the horse's eye. I remember as a child I would lose all my dogs to death, and the baby lamb that my step dad brought home. In that case, we can't What I love about Steinbeck is that his simple narrative always becomes multilayered upon its conclusion. Thanks for telling us about the problem. Welcome back. Nellie becomes very ill. Related Searches. So much depth in so few pages! I think that is why the novel resonates. Jan 21, Andy rated it really liked it. May 10, David R. He acknowledges that his stories may be tiresome, but explains:. Summary Summary. The narration I have given three stars. Goonther I hope not, oh god please no. First book edition. It's always fun to read John Steinbeck books. In each story Steinbeck shows us unique ways in which young Jody undergoes certain experiences as he confronts the harsh realities of life, and as a result comes closer to a realization of true manhood — facts adults must live with: sickness, age, death, procreation, birth. From the look of the cover and title, you'd think you'd be reading a happy little novella about a boy and his horse, but it's so much more than that. -

Alienation and Reconciliation in the Novels

/!/>' / /¥U). •,*' Ow** ALIENATION AND RECONCILIATION IN THE NOVELS OF JOHN STEINBECK APPROVED! Major Professor lflln<^^ro^e3s£r^' faffy _g.£. Director of the Department of English Dean of *the Graduate School ALIENATION AND RECONCILIATION IN THE NOVELS OF JOHN STEINBECK THESIS Pras8nted to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of WASTER OF ARTS By Barbara Albrecht McDaniel, B. A. Denton, Texas May, 1964 TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page I. INTRODUCTION! SCOPE OF STUDY AND REVIEW OF CRITICISM ......... 1 II. VALUES 19 %a> III. ALIENATION . 61 IV. RECONCILIATION 132 V. CONCLUSION . ... ... 149 •a S . : BIBLIOGRAPHY . • . 154 §9 ! m I i • • • . v " W ' M ' O ! . • ' . • ........•; i s. ...... PS ! - ' ;'s -•••' • -- • ,:"-- M | J3 < fc | • ' . • :v i CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION: SCOPE OF STUDY AND REVIEW OF CRITICISM On October 25, 1962, the world learned that John Stein- beck had won the 1962 Nobel Prize for Literature* In citing him as the sixth American to receive this award meant for the person M,who shall have produced in the field of literature the most distinguished work of an idealistic tendency,'"^ the official statement from the Swedish Academy said, "'His sym- pathies always go out to the oppressed, the misfits, and the distressed. He likes to contrast the simple joy of life with 2 the brutal and cynical craving for money*1,1 These sympa- thies and contrasts are brought out in this thesis, which purports to synthesize the disparate works of John Steinbeck through a study of the factors causing alienation and recon- ciliation of the characters in his novels* Chapters II, III, and IV of this study present ideas that, while perhaps not unique, were achieved through an in- dependent study of the novels. -

READING JOHN STEINBECK ^ Jboctor of $Iitldfi

DECONSTRUCTING AMERICA: READING JOHN STEINBECK ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF ^ JBoctor of $IitlDfi;opI)p IN ENGLISH \ BY MANISH SINGH UNDER THE SUPERVISION OF DR. MADIHUR REHMAN DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH (INDIA) 2013 Abstract The first chapter of the thesis, "The Path to Doom: America from Idea to Reality;'" takes the journey of America from its conception as an idea to its reality. The country that came into existence as a colony of Great Britain and became a refuge of the exploited and the persecuted on one hand and of the outlaws on other hand, soon transformed into a giant machine of exploitation, persecution and lawlessness, it is surprising to see how the noble ideas of equality, liberty and democracy and pursuit of happiness degenerated into callous profiteering. Individuals insensitive to the needs and happiness of others and arrogance based on a sense of racial superiority even before they take root in the virgin soil of the Newfoundland. The effects cf this degenerate ideology are felt not only by the Non-White races within America and the less privileged countries of the third world, but even by the Whites within America. The concepts of equality, freedom, democracy and pursuit of happiness were manufactured and have been exploited by the American ruling class.The first one to experience the crawling effects of the Great American Dream were original inhabitants of America, the Red Indians and later Blacks who were uprooted from their home and hearth and taken to America as slaves. -

![Archons (Commanders) [NOTICE: They Are NOT Anlien Parasites], and Then, in a Mirror Image of the Great Emanations of the Pleroma, Hundreds of Lesser Angels](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8862/archons-commanders-notice-they-are-not-anlien-parasites-and-then-in-a-mirror-image-of-the-great-emanations-of-the-pleroma-hundreds-of-lesser-angels-438862.webp)

Archons (Commanders) [NOTICE: They Are NOT Anlien Parasites], and Then, in a Mirror Image of the Great Emanations of the Pleroma, Hundreds of Lesser Angels

A R C H O N S HIDDEN RULERS THROUGH THE AGES A R C H O N S HIDDEN RULERS THROUGH THE AGES WATCH THIS IMPORTANT VIDEO UFOs, Aliens, and the Question of Contact MUST-SEE THE OCCULT REASON FOR PSYCHOPATHY Organic Portals: Aliens and Psychopaths KNOWLEDGE THROUGH GNOSIS Boris Mouravieff - GNOSIS IN THE BEGINNING ...1 The Gnostic core belief was a strong dualism: that the world of matter was deadening and inferior to a remote nonphysical home, to which an interior divine spark in most humans aspired to return after death. This led them to an absorption with the Jewish creation myths in Genesis, which they obsessively reinterpreted to formulate allegorical explanations of how humans ended up trapped in the world of matter. The basic Gnostic story, which varied in details from teacher to teacher, was this: In the beginning there was an unknowable, immaterial, and invisible God, sometimes called the Father of All and sometimes by other names. “He” was neither male nor female, and was composed of an implicitly finite amount of a living nonphysical substance. Surrounding this God was a great empty region called the Pleroma (the fullness). Beyond the Pleroma lay empty space. The God acted to fill the Pleroma through a series of emanations, a squeezing off of small portions of his/its nonphysical energetic divine material. In most accounts there are thirty emanations in fifteen complementary pairs, each getting slightly less of the divine material and therefore being slightly weaker. The emanations are called Aeons (eternities) and are mostly named personifications in Greek of abstract ideas. -

America and Americans: and Selected Nonfiction Free

FREE AMERICA AND AMERICANS: AND SELECTED NONFICTION PDF John Steinbeck,Jackson J Benson,Susan Shillinglaw | 448 pages | 28 Jul 2004 | Penguin Putnam Inc | 9780142437414 | English | New York, NY, United States America and Americans and Selected Nonfiction by John Steinbeck, Paperback | Barnes & Noble® Goodreads helps you keep track of books you want to America and Americans: And Selected Nonfiction. Want to Read saving…. Want to America and Americans: And Selected Nonfiction Currently Reading Read. Other editions. Enlarge cover. Error rating book. Refresh and try again. Open Preview See a Problem? Details if other :. Thanks for telling us about the problem. Return to Book Page. Jackson J. Benson Editor. Susan Shillinglaw Editor. More than four decades after his death, John Steinbeck remains one of the nation's most beloved authors. Yet few know of his career as a journalist who covered world events from the Great Depression to Vietnam. Now, this distinctive collection offers a portrait of the artist as citizen, deeply engaged in the world around him. In addition to the complete text of Steinbeck's More than four decades after his death, John Steinbeck remains one of the nation's most beloved authors. In addition to the complete text of Steinbeck's last published book, America and Americansthis volume brings together for the America and Americans: And Selected Nonfiction time more than fifty of Steinbeck's finest essays and journalistic pieces on Salinas, Sag Harbor, Arthur Miller, Woody Guthrie, the Vietnam War and more. For more than seventy years, Penguin has been the America and Americans: And Selected Nonfiction publisher of classic literature in the English- speaking world. -

Starfarer's Handbook

Requires the use of the Dungeons & Dragons® Player's Handbook starfarer s handbook credits ORIGINAL CREATION PRINTING Greg Benage Quebecor Printing, Inc. Printed in Canada WRITING AND DESIGN PLAYTESTING AND FEEDBACK Greg Benage and Matt Forbeck Chad Boyer, Andrew Christian, Mike Coleman, INTERIOR ILLUSTRATIONS Jacob Driscoll, Claus Emmer, Greg Frantsen, Tod Gelle, Jason Kemp, Tracy McCormick, Ragin Andy Brase, Darren Calvert, Mitch Cotie, Jesper Miller, Brian Schomburg, Erik Terrell, Chris White, Ejsing, David Griffith, Dave Lynch, Klaus Brian Wood, and everyone on the Dragonstar mail- Scherwinksi, Brian Schomburg, Simone Bianchi, ing list Jean-Pierre Targete, Kieran Yanner GRAPHIC DESIGN GREG’S DEDICATION Brian Schomburg To my moms, who gave me the world and taught COVER DESIGN me to dream of the stars. Brian Schomburg MATT’S DEDICATION EDITING AND LAYOUT To George Lucas and Dave Arneson & E. Gary Greg Benage Gygax for firing my generation's imagination. ART DIRECTION Brian Wood ‘d20 System’ and the d20 System logo are PUBLISHER Trademarks owned by Wizards of the Coast and are used with permission. Christian T. Petersen Dungeons & Dragons® and Wizards of the Coast® are Registered Trademarks of Wizards of the Coast, and are used with Permission. FANTASY FLIGHT GAMES 1975 W. County Rd. B2 #1 Dragonstar © 2001, Fantasy Flight, Inc. Roseville, MN 55113 All rights reserved. 651.639.1905 www.fantasyflightgames.com contents CHAPTER 1: WELCOME TO DRAGONSTAR . .4 CHAPTER 2: RACES . .17 CHAPTER 3: CLASSES . .35 CHAPTER 4: SKILLS . .70 CHAPTER 5: FEATS . .85 CHAPTER 6: EQUIPMENT . .91 CHAPTER 7: COMBAT . .124 CHAPTER 8: MAGIC . .136 CHAPTER 9: VEHICLES . .150 Introduction The Open Game License The Dragonstar Starfarer’s Handbook is published 3 Fantasy Flight Games is pleased to present under the terms of the Open Game License and the d20 Dragonstar, a unique space fantasy campaign setting System Trademark License. -

Introduction the Quest the Process and Resources

Name: Period: Date: Of Mice and Men WebQuest Introduction You are about to embark on a WebQuest to discover what life was like in the 1930s. Of Mice and Men is set in California during the Great Depression. It follows two migrant workers, George and Lennie, as they struggle to fulfill their dreams. In order to better understand their plight, you will be exploring several websites to increase your background knowledge before getting into the book. Check out the websites listed below to help you answer the following questions. The Quest What are the background issues that led to Steinbeck's writing of this novella about profound friendship and social issues? First complete the Great Depression simulation on your own to gather some background knowledge. Then begin the research with your group. The Process and Resources In this WebQuest you will be working and exploring web pages to answer questions in your designated section. Each member in your group is assigned a role. You are responsible for answering the questions for your role and sharing that information with your group. Together you will create a presentation that includes information from each group member’s research. Group Members: ____________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ My Role: __________________________________________ Name: Period: Date: Geographers: The geography of Of Mice and Men Setting in Of Mice and Men Salinas farm country John Steinbeck and Salinas, California Steinbeck Country Geographers' Questions: 1. What are the geographical features of California’s Salinas River Valley? 2. What is the Salinas Valley known as? 3. What kinds of jobs are available there? 4. -

22 Tightbeam

22 TIGHTBEAM Those multiple points of connection—and favorites—indicate the show’s position of preference in popular culture, and Tennant said he’s consistently surprised by how Doctor Who fandom and awareness has spread internationally—despite its British beginnings. “Doctor Who is part of the cultural furniture in the UK,” he said. “It’s something that’s uniquely British, that Britain is proud of, and that the British are fascinated by.” Now, when Tennant is recognized in public, he can determine how much a fan of the show the person is based on what they say to him. “If someone says, ‘Allons-y!’ chances are they’re a fan,” he said. Most people say something like, “Where’s your Tardis?” or “Aren’t you going to fix that with your sonic screwdriver?” There might be one thing that all fans can agree on. Perhaps—as Tennant quipped—Doctor Who Day, Nov. 23 (which marks the airing of the first episode, “An Unearthly Child”) should be a national holiday. Regardless of what nation—or planet—you call home. Note: For a more in-depth synopsis of the episodes screened, visit https://tardis.fandom.com/ wiki/The_End_of_Time_(TV_story). To see additional Doctor Who episodes screened by Fath- om, go to https://tardis.fandom.com/wiki/Fathom_Events. And if you’d like to learn about up- coming Fathom screenings, check out https://www.fathomevents.com/search?q=doctor+who. The episodes are also available on DVD: https://amzn.to/2KuSITj. The Dark Crystal: Age of Resistance on Netflix Review by Jim McCoy (I would never do this before a book review, but I doubt that the people at Netflix would mind, so here goes: I'm geeked. -

Nationalsteinbeckcenter News Issue 70 | December 2017

NATIONALSTEINBECKCENTER NEWS ISSUE 70 | DECEMBER 2017 Drawing of Carol Henning Steinbeck, John’s frst wife Notes From the Director Susan Shillinglaw The National Steinbeck Center has enjoyed a busy, productive It may be well to consider Steinbeck’s role in each of these NSC fall: a successful National Endowment for the Arts Big Read of programs—all of which can be linked to his fertile imagination Claudia Rankine’s Citizen; a delightful staged reading of Over the and expansive, restless curiosity. John Steinbeck was a reader River and Through the Woods in the museum gallery as part of of comics, noting that “Comic books might be the real literature our Performing Arts Series, produced by The Listening Place; a of our time.” He was passionate about theater—Of Mice and robust dinner at the Corral de Tierra Country Men, written in 1937, was a play/novelette, an experiment in Club, the 12th annual Valley of the World writing a novel that could also be performed exactly as written fundraiser celebrating agricultural on stage (he would go on to write two more play/novelettes). leaders in the Salinas Valley; and the He wrote often and thoughtfully about American’s racial legacy, upcoming 4th annual Salinas Valley and Rankine’s hybrid text--part poetry, part nonfiction, part Comic Con, co-sponsored by the Salinas image, part video links—would no doubt intrigue a writer who Public Library and held at Hartnell insisted that every work of prose he wrote was an experiment: College in December—“We “I like experiments. They keep the thing alive,” he wrote in are Not Alone.” All are covered 1936. -

![When Men Give Birth: Production and Reproduction in John Steinbeck’S Selected Works ]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0238/when-men-give-birth-production-and-reproduction-in-john-steinbeck-s-selected-works-900238.webp)

When Men Give Birth: Production and Reproduction in John Steinbeck’S Selected Works ]

[ostrava journal of english philology—vol.12, no.1, 2020—literature and culture] [ISSN 1803-8174 (print), ISSN 2571-0257 (online)] 45 [doi.org/10.15452/OJoEP.2020.12.0004] [ When Men Give Birth: Production and Reproduction in John Steinbeck’s Selected Works ] Karla Rohová University of Ostrava [Abstract] The main goal of this paper is to reach beneath the surface of John Steinbeck’s literary works in order to analyse the metaphorical connections between the long ‑term violence, abuse or oppression of women and the depletion of the land portrayed in several of his novels. For this purpose, excerpts dealing with the topic of production and reproduction in the works In Dubious Battle, To a God Unknown, “The Forgotten Village”, East of Eden and The Grapes of Wrath are analysed to explore Steinbeck’s depiction of the connection between the land and the female body. [Keywords] production; reproduction; ecofeminism; John Steinbeck; nature; land; ecology; women; metaphor; California; agriculture This text is an output of the project SGS04/FF/2019 “Ecocritical Perspectives on 20th and 21st‑Century American Literature” supported by the internal grant scheme of the University of Ostrava. [ostrava journal of english philology —literature and culture] 46 [Karla Rohová—When Men Give Birth: Production and Reproduction in John Steinbeck’s Selected Works] [ 1 ] Introduction The connection to the land can be seen in almost every book by John Steinbeck. In the past two decades, the author has been resurrected especially by environmental critics. Nevertheless, there is one figure which frequently recurs in his work and is specifically characteristic of the author’s perception of nature – a woman. -

By Poul Anderson Change Without Notice Before, During, Or After the Convention

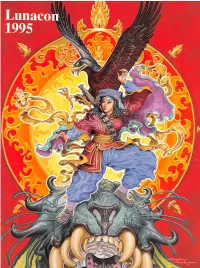

NEW EMPIRES Expansion Set!!! i. Four All New Empires! .A 0 Entity (ultra rare) cards found only in the first print run! r Basic Deck C - CGE1120450 nonrandom cards) $6.95 ea. 127display Expansion Packs - CGE5110 (12 random cards) $2.45 ea. 36/Display ! GALACTIC EMPIRES™ Primary Edition: The 430 card major release! First print run going, going... will beholding Fantastic Graphics and illustrations! s half hour demonstrations games of Eight different empires! Plus 9 Entity (ultra rare) cards found only in the first print run! Galactic Empires in the gaming section. The Basic Deck A & B - CGE1110 (55 cards, 50 nonrandom) demonstrations of Galactic Empires will be $8.95ea. 12/display hosted by designers C. Henry Schulte and Expansion Packs - CGE4110 (12 random) $2.45 ea. 36/Display Richard J. Rausch. Every person who partici Limited Edition Prints (500 signed & numbered) Coming Soon! pates in the demonstration games will receive CLP0001 - ‘Assault on a Clydon Bridge’ (this illustration 20x24) $39.95 Illustration © 1995 Douglas Chaffee. an ultra-rare ‘entity’ card. Call Companion Games for Details: 1-800-49-GAMES or 607-652-9038 The New York Science Fiction Society — The Lunarians, Inc. presents: Lunacon 1995 March 17 - 19 Rye Town Hilton Rye Brook, New York Writer Guest of Honor Poul Anderson Artist Guest of Honor Stephen F. Hickman Fan Guest of Honor: Mike Glyer Featured Filker: Graham Leathers I TOR SALUTES LUNACON GUEST OF HONOR POUL ANDERSON the Hugo and Nebula-award winning SF Grand Master! Don’t miss THE STARS ARE ALSO FIRE, Poul Anderson’s