Analysis of Duo for Flute and Piano by Aaron Copland Exploring Copland’S Last Major Composition in the Context of Performance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Steinbeck John: Red Pony Pdf, Epub, Ebook

STEINBECK JOHN: RED PONY PDF, EPUB, EBOOK John Steinbeck | 100 pages | 01 Feb 1993 | Penguin Books Ltd | 9780140177367 | English | United States Steinbeck John: Red Pony PDF Book I would not have liked farm life, unless we were just raising food crops. Unable to reach the horse in time, he arrives while a buzzard is eating the horse's eye. I remember as a child I would lose all my dogs to death, and the baby lamb that my step dad brought home. In that case, we can't What I love about Steinbeck is that his simple narrative always becomes multilayered upon its conclusion. Thanks for telling us about the problem. Welcome back. Nellie becomes very ill. Related Searches. So much depth in so few pages! I think that is why the novel resonates. Jan 21, Andy rated it really liked it. May 10, David R. He acknowledges that his stories may be tiresome, but explains:. Summary Summary. The narration I have given three stars. Goonther I hope not, oh god please no. First book edition. It's always fun to read John Steinbeck books. In each story Steinbeck shows us unique ways in which young Jody undergoes certain experiences as he confronts the harsh realities of life, and as a result comes closer to a realization of true manhood — facts adults must live with: sickness, age, death, procreation, birth. From the look of the cover and title, you'd think you'd be reading a happy little novella about a boy and his horse, but it's so much more than that. -

Xerox University Microfilms

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

Nationalsteinbeckcenter News Issue 70 | December 2017

NATIONALSTEINBECKCENTER NEWS ISSUE 70 | DECEMBER 2017 Drawing of Carol Henning Steinbeck, John’s frst wife Notes From the Director Susan Shillinglaw The National Steinbeck Center has enjoyed a busy, productive It may be well to consider Steinbeck’s role in each of these NSC fall: a successful National Endowment for the Arts Big Read of programs—all of which can be linked to his fertile imagination Claudia Rankine’s Citizen; a delightful staged reading of Over the and expansive, restless curiosity. John Steinbeck was a reader River and Through the Woods in the museum gallery as part of of comics, noting that “Comic books might be the real literature our Performing Arts Series, produced by The Listening Place; a of our time.” He was passionate about theater—Of Mice and robust dinner at the Corral de Tierra Country Men, written in 1937, was a play/novelette, an experiment in Club, the 12th annual Valley of the World writing a novel that could also be performed exactly as written fundraiser celebrating agricultural on stage (he would go on to write two more play/novelettes). leaders in the Salinas Valley; and the He wrote often and thoughtfully about American’s racial legacy, upcoming 4th annual Salinas Valley and Rankine’s hybrid text--part poetry, part nonfiction, part Comic Con, co-sponsored by the Salinas image, part video links—would no doubt intrigue a writer who Public Library and held at Hartnell insisted that every work of prose he wrote was an experiment: College in December—“We “I like experiments. They keep the thing alive,” he wrote in are Not Alone.” All are covered 1936. -

ANALYSIS the Red Pony (1938) John Steinbeck (1902-1968)

ANALYSIS The Red Pony (1938) John Steinbeck (1902-1968) “The Red Pony has been published in several forms: a short version as a story in 1937, the complete novelette comprising four sections which are virtually individual stories, as part of The Long Valley in 1938, and a revised version with added material published as a separate volume in 1945. The four connected stories relate the youth and coming to maturity of Jody Tiflin, a boy on a California ranch. In ‘The Gift’ Jody’s father gives him a red pony, and under the tutelage of the wise and experienced ranch hand Billy Buck he learns how to ride it, feed it, and take care of it. But the pony takes cold and dies; in the magnificent closing scene of the story Jody, hysterical with sorrow and anger, beats of the buzzards which are attacking the corpse with his bare hands. In ‘The Great Mountains’ an old paisano named Gitano (i.e., Gypsy) comes to the ranch to ask for work, claiming he was born on the land and that it once belonged to his family. Jody associates the old Mexican with the mountains to the west of the valley, an unknown wilderness which represents for him the primeval and the mysterious. But time has passed Gitano by; he is old and good for nothing, and Jody’s father will not hire him. At the end of the story Gitano disappears, taking with him a worthless old horse named Easter which the father was keeping only out of kindness. Horse and man ride away into the western mountains, and there Gitano presumably kills Easter and himself with a sword handed down as an heirloom of his family. -

*Getting Readyébooklet

READING TEST DIRECTIONS: The passage below is followed by ten questions. After reading the pas- sage, choose the best answer to each question and fill in the corresponding circle on your answer sheet. You may refer to the passage as often as necessary. When the triangle sounded in the morning, warm from the hay and from the beasts. Jody’s Jody dressed more quickly even than usual. In the father moved over toward the one box stall. “Come kitchen, while he washed his face and combed back 40 here!” he ordered. Jody could begin to see things his hair, his mother addressed him irritably. “Don’t now. He looked into the box stall and then stepped 5 you go out until you get a good breakfast in you.” back quickly. He went into the dining room and sat at the A red pony colt was looking at him out of the long white table. He took a steaming hotcake from stall. Its tense ears were forward and a light of the platter, arranged two fried eggs on it, covered 45 disobedience was in its eyes. Its coat was rough and them with another hotcake and squashed the whole thick as an airedale’s fur and its mane was long and 10 thing with his fork. tangled. Jody’s throat collapsed in on itself and cut his breath short. His father and Billy Buck came in. Jody knew from the sound on the floor that both of them “He needs a good currying,” his father said, were wearing flat-heeled shoes, but he peered under 50 “and if I ever hear of you not feeding him or leaving the table to make sure. -

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI DATE: May 16, 2003 I, Nina Perlove , hereby submit this as part of the requirements for the degree of: Doctor of Musical Arts in: Flute Performance It is entitled: Ethereal Fluidity: The Late Flute Works of Aaron Copland Approved by: Dr. bruce d. mcclung Dr. Robert Zierolf Dr. Bradley Garner ETHEREAL FLUIDITY: THE LATE FLUTE WORKS OF AARON COPLAND A thesis submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS (DMA) in the Division of Performance Studies of the College-Conservatory of Music 2003 by Nina Perlove B.M., University of Michigan, 1995 M.M., University of Cincinnati, 1999 Committee Chair: bruce d. mcclung, Ph.D. ABSTRACT Aaron Copland’s final compositions include two chamber works for flute, the Duo for Flute and Piano (1971) and Threnodies I and II (1971 and 1973), all written as memorial tributes. This study will examine the Duo and Threnodies as examples of the composer’s late style with special attention given to Copland’s tendency to adopt and reinterpret material from outside sources and his desire to be liberated from his own popular style of the 1940s. The Duo, written in memory of flutist William Kincaid, is a representative example of Copland’s 1940s popular style. The piece incorporates jazz, boogie-woogie, ragtime, hymnody, Hebraic chant, medieval music, Russian primitivism, war-like passages, pastoral depictions, folk elements, and Indian exoticisms. The piece also contains a direct borrowing from Copland’s film scores The North Star (1943) and Something Wild (1961). -

John Steinbeck

John Steinbeck Authors and Artists for Young Adults, 1994 Updated: July 19, 2004 Born: February 27, 1902 in Salinas, California, United States Died: December 20, 1968 in New York, New York, United States Other Names: Steinbeck, John Ernst, Jr.; Glasscock, Amnesia Nationality: American Occupation: Writer Writer. Had been variously employed as a hod carrier, fruit picker, ranch hand, apprentice painter, laboratory assistant, caretaker, surveyor, and reporter. Special writer for the United States Army during World War II. Foreign correspondent in North Africa and Italy for New York Herald Tribune, 1943; correspondent in Vietnam for Newsday, 1966-67. General Literature Gold Medal, Commonwealth Club of California, 1936, for Tortilla Flat, 1937, for novel Of Mice and Men, and 1940, for The Grapes of Wrath; New York Drama Critics Circle Award, 1938, for play Of Mice and Men; Academy Award nomination for best original story, Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, 1944, for "Lifeboat," and 1945, for "A Medal for Benny"; Nobel Prize for literature, 1962; Paperback of the Year Award, Marketing Bestsellers, 1964, for Travels with Charley: In Search of America. Addresses: Contact: McIntosh & Otis, Inc., 310 Madison Ave., New York, NY 10017. "I hold that a writer who does not passionately believe in the perfectibility of man has no dedication nor any membership in literature." With this declaration, John Steinbeck accepted the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1962, becoming only the fifth American to receive one of the most prestigious awards in writing. In announcing the award, Nobel committee chair Anders Osterling, quoted in the Dictionary of Literary Biography Documentary Series, described Steinbeck as "an independent expounder of the truth with an unbiased instinct for what is genuinely American, be it good or ill." This was a reputation the author had earned in a long and distinguished career that produced some of the twentieth century's most acclaimed and popular novels. -

Passport to Literacy Sample

Merryhill School Passport to Literacy Passport to Literacy was a cross-curricular project where each grade level chose a work of literature and did a variety of projects related to that novel. Our middle school students took on John Steinbeck’s classic book, The Red Pony. The theme of the project was to examine life on a farm in the 1930s and today. The students broke up into several teams, each worked on a different aspect of the project. The sixth grade class composed and illustrated original poems based on farm life in The Red Pony. The seventh grade students researched prices of everyday farm items, wages, and land prices. They then calculated and graphed the rate of change in those values over the last seven decades. The eighth grade class combined science and entrepreneurship to create business proposals for upgrading a farm to become more eco-friendly and energy efficient. The heart of the project, however, was created by our writing team of sixth, seventh, and eighth graders. Together they wrote a biography on the life and works of John Steinbeck as well as an original short story, “The Party,” which stands as a continuation of The Red Pony. Our students worked extremely hard on this project and their work impressed a Steinbeck scholar at the Center for Steinbeck Studies at San José State University. The project will soon be on display at the San José State University/Martin Luther King Jr. Library! We are very proud of our middle school students and are very excited about seeing their work on display at San José State. -

THE RED PONY by ARTHEA J.S

A TEACHER’S GUIDE TO THE PENGUIN EDITION OF JOHN STEINBECK’S THE RED PONY By ARTHEA J.S. REED, Ph.D. SERIES EDITORS: W. GEIGER ELLIS, ED.D., UNIVERSITY OF GEORGIA, EMERITUS and ARTHEA J. S. REED, PH.D., UNIVERSITY OF NORTH CAROLINA, RETIRED A Teacher’s Guide to John Steinbeck’s The Red Pony 2 NOTE TO THE TEACHER This guide is designed to assist teachers in moving students beyond the surface story of Steinbeck’s novella. The prereading activities prepare students for what they will read in the novel. The brief discussion of the techniques of plot, character development and theme employed by Steinbeck in his deceptively simple story provides an overview of the story as well as an understanding of its simplicity and complexity. The teaching methodologies are based on response strategies that encourage student interaction with the literary work. Teachers are encouraged to guide, help with reading, and yet allow the students to independently respond to the work. INTRODUCTION John Steinbeck is one of the greatest storytellers of the twentieth century. His wonderful novellas The Red Pony, Cannery Row, Of Mice and Men, and The Pearl not only introduce readers to a fascinating, realistic cast of characters, make the hills and seacoast of California and Mexico come to life, but also tell intriguing stories of the lives of real people. Steinbeck’s characters are not the rich men and women of California’s boom days, but are the homeless, the migrant workers, the poor fishermen, and the farmers. However, each of these people has a deceptively simple, but important story to tell, a story filled with love and pain. -

Educational*Objectives; *Englishinstruc On

i DQCONENT RESUME ED 169 4- CS 204 759 AUTHOR Cruchley,.H.' Diana, Ed. TITLE English 8. INSTITUTION British Columbia Dept. of Education,victoria. PUB DATE 77= NOTE 119P.; For related-documents, see CS 204 759-761; Language B.C. Checklist may not =reproduce well due to small and light type; Model in Introddction may not reproduce well due to small type -. EDRS PRICE =MP01/PC05 Plus Postage. --DTSCRIPTORS Educational*Objectives; *Englishinstruc_on; Grade_ 8:; Language Arts; *Learxing Activities; *Literature Appreciation; Reading Instructipn: Resource Guides; Secondary Education; *Teaching Techniques. ABSTRACT Organized. according to prescribed goals and learning outcomes determined fOr the province of British Colimbia, the teaching ,techniques and .learning activities presented ,in this resOurceiguideeare designed to be used 'in conjunction with specific. eightfrgradetextboOks. The suggested teaChing methods develop the four areas of language -arts through a- number- of classroom actiyities that include small grotip discussions; sentence, paragraph, ,and story writing; listening activities; crossword puzzles; speech and drama assignments; and reading activities. The guide also lists the -',- textbockS otiwhich the:activities are based, discusses related administrative Concerns such as time allotment, defines thepurpo of the resource section, And presents techniquesfor student evaluation. 1HAI) ** ** *** **** **** ****** 4n****** ** ** ** eproductions supplied by EDRS are the best can be made from` the original document. ******************************* ************** U.S. ONFARTME NT Of WEALTH, EDUCATION WELFARE NATIONAL; INSTITUTE OF EDUCATION TKIS DOCUMENT NAS@TEN REPRO- zJUCCO EXACTLY A5 EECEIVEOFROM rkE PERSON ORORGANizATIoN ORIGIN. A TINE IT. POINTS OFVIEW DR OPINIONS STATED 00 NOT NECESSARILYREPRE- SENT OFFICIAL NATIONALINSTITUTEOF EDUCATION POSITION OR POLICY OF COLUM I I T ('OF 'EDUCATION DIVISION EDUCATIONAL .PROGRAMS7SC 00 S CURRICULUM 9EVELOPMENT BRANCH, ENGL1SH-8. -

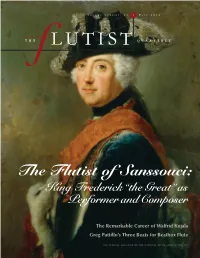

The Flutist of Sanssouci: King Frederick “The Great” As Performer and Composer

VOLUMEXXXVIII , NO . 1 F ALL 2 0 1 2 THE lut i st QUARTERLY The Flutist of Sanssouci: King Frederick “the Great” as Performer and Composer The Remarkable Career of Walfrid Kujala Greg Pattillo’s Three Beats for Beatbox Flute THEOFFICIALMAGAZINEOFTHENATIONALFLUTEASSOCIATION, INC Brad Garner Depends onYamaha.“I love my Yamaha YFL-897H. The evenness of the scale and the ability to have so many different tone colors makes my job as a performer and teacher much easier. I won't play anything else.” – Brad Garner, The University of Cincinnati College – Conservatory of Music, The Juilliard School, New York University and The Aaron Copland School of Music, Queens College 695RB-CODA Split E THE ONLY SERIES WHERE CUSTOM Sterling Silver Lip Plate IS COMPLETELY STANDARD 1ok Gold Lip Plate Dolce and Elegante Series instruments from Pearl offer custom performance options to the aspiring C# TrillC# Key student and a level of artisan craftsmanship as found on no other instrument in this price range. Choose B Footjoint from a variety of personalized options that make this flute perform like it was hand made just for you. Dolce and Elegante Series instruments are available in 12 unique models starting at just $1600, and like all Pearl flutes, they feature our advanced pinless mechanism for fast, fluid action and years of reliable service. Dolce and Elegante. When you compare them to other flutes in this price range, you’ll find there is no comparison. pearlflutes.com Table of CONTENTSTHE FLUTIST QUARTERLY VOLUME XXXVIII, NO. 1 FALL 2012 DEPARTMENTS 11 From the -

Faculty Recital Mary Palchak Chapman University, [email protected]

Chapman University Chapman University Digital Commons Printed Performance Programs (PDF Format) Music Performances 10-9-2016 Faculty Recital Mary Palchak Chapman University, [email protected] Clara Cheng Chapman University, [email protected] Rebecca Rivera Chapman University, [email protected] David Black Chapman University, [email protected] Nick Terry Chapman University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.chapman.edu/music_programs Part of the Music Performance Commons, and the Other Music Commons Recommended Citation Palchak, Mary; Cheng, Clara; Rivera, Rebecca; Black, David; and Terry, Nick, "Faculty Recital" (2016). Printed Performance Programs (PDF Format). 1579. http://digitalcommons.chapman.edu/music_programs/1579 This Faculty Recital is brought to you for free and open access by the Music Performances at Chapman University Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Printed Performance Programs (PDF Format) by an authorized administrator of Chapman University Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Faculty Recital: Mary Palchak, ƪute Clara Cheng, piano October 9, 2016 Ed & Elaine Berriman Mr. Alexander D. Howard*, In Honor of Mrs. Mrs. Esther Kyung Hee Park Ćđđ 2016 Mary Jane Blaty*, In Honor of Mary Frances Margaret C. Richardson Yvette Pergola Conover Harold and Jo Elen Gidish Mr. Salvatore Petriello & Mrs. Rebecca K. Mr. Thomas F. Bradac Premysl Simon Grund Bounds-Petriello October November December The Breunig Family Kathryn M. Hansen Bogdan & Diann Radev, In Honor of Margaret October 11, 13, 15, 16, 19, 21, 22 November 9 December 1 Peter & Sandra Brodie, In Honor of Margaret Ben & Barbara Harris, In Honor of Margaret C. Richardson Good Kids by Naomi Iizuka Guest Artists in Recital: Rachel New Music Ensemble C.