This Is an Open Access Document Downloaded from ORCA, Cardiff University's Institutional Repository

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cardiff Airport and Gateway Development Zone SPG 2019

Vale of Glamorgan Local Development Plan 2011- 2026 Cardiff Airport and Gateway Development Zone Supplementary Planning Guidance Local Cynllun Development Datblygu December 2019 Plan Lleol Vale of Glamorgan Local Development Plan 2011-2026 Cardiff Airport & Gateway Development Zone Supplementary Planning Guidance December 2019 This document is available in other formats upon request e.g. larger font. Please see contact details in Section 9. CONTENTS 1. Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... 1 2. Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 2 3. Purpose of the Supplementary Planning Guidance .................................................................... 3 4. Status of the Guidance .............................................................................................................. 3 5. Legislative and Planning Policy Context .................................................................................... 4 5.1. National Legislation ............................................................................................................. 4 5.2. National Policy Context ....................................................................................................... 4 5.3. Local Policy Context ............................................................................................................ 5 5.4. Supplementary Planning -

GB 0214 D387 Cld

GLAMORGAN RECORD OFFICE/ARCHIFDY MORGANNWG Reference code: GB 0214 D387 Title: Anthony M. Ernest and Robert M. Ernest of Penarth Papers Dates : [circa 1928]-2007 Level of description: Fonds Extent and medium: 0.10 cubic metres; 5 boxes Name of creator(s): Robert M. Ernest (1904-1991) and Anthony M. Ernest (1936-) Administrative/biographical history Robert Monroe Ernest (1904-1991) was born in Cartago, Costa Rica, the son of John Robert Ernest of Dundee and Elizabeth Monroe of Hartlepool, later of Penarth. His father's work as a Master Mariner led him to Costa Rica, where he settled with his family. John established a successful coffee plantation of some 3000 acres, 'Rosemount Estates' in Cartago Province, along with the 'Juan Vinas Concrete Products Co. Ltd', which manufactured concrete paving and kerbstones from imported South Wales Portland cement. John and Elizabeth raised five sons in Costa Rica, and sold their thriving estate to the country's government in 1947. Robert Monroe Ernest was educated at Westwood College, Penarth, travelling back to Costa Rica by sea for the long summer break. In the early 1930s he purchased the Costa Rica Coffee Co. Ltd., coffee and tea importers and merchants based at 14 Dumfries Place, Cardiff, from his uncle Ralph. The company moved to 1 and 2 Great Western Approach sometime around 1938. This allowed for expansion in response to trade with UK hotels and restaurants, in particular the Italian owned cafes of the south Wales valleys. The company purchased coffee from the family estate along with most of the principal coffee producing countries of the world. -

Advice to Inform Post-War Listing in Wales

ADVICE TO INFORM POST-WAR LISTING IN WALES Report for Cadw by Edward Holland and Julian Holder March 2019 CONTACT: Edward Holland Holland Heritage 12 Maes y Llarwydd Abergavenny NP7 5LQ 07786 954027 www.hollandheritage.co.uk front cover images: Cae Bricks (now known as Maes Hyfryd), Beaumaris Bangor University, Zoology Building 1 CONTENTS Section Page Part 1 3 Introduction 1.0 Background to the Study 2.0 Authorship 3.0 Research Methodology, Scope & Structure of the report 4.0 Statutory Listing Part 2 11 Background to Post-War Architecture in Wales 5.0 Economic, social and political context 6.0 Pre-war legacy and its influence on post-war architecture Part 3 16 Principal Building Types & architectural ideas 7.0 Public Housing 8.0 Private Housing 9.0 Schools 10.0 Colleges of Art, Technology and Further Education 11.0 Universities 12.0 Libraries 13.0 Major Public Buildings Part 4 61 Overview of Post-war Architects in Wales Part 5 69 Summary Appendices 82 Appendix A - Bibliography Appendix B - Compiled table of Post-war buildings in Wales sourced from the Buildings of Wales volumes – the ‘Pevsners’ Appendix C - National Eisteddfod Gold Medal for Architecture Appendix D - Civic Trust Awards in Wales post-war Appendix E - RIBA Architecture Awards in Wales 1945-85 2 PART 1 - Introduction 1.0 Background to the Study 1.1 Holland Heritage was commissioned by Cadw in December 2017 to carry out research on post-war buildings in Wales. 1.2 The aim is to provide a research base that deepens the understanding of the buildings of Wales across the whole post-war period 1945 to 1985. -

Cystic Fibrosis Centre: University Hospital Llandough Design and Access Statement

Cystic Fibrosis Centre: University Hospital Llandough Design and Access Statement DRAFT - October 2018 Prepared by: Harri Aston and Mark Farrar Address: The Urbanists, The Creative Quarter, 8A Morgan Arcade, Cardiff, CF10 1AF, United Kingdom Email: [email protected] / [email protected] Website: www.theurbanists.net Issue date -- | -- | -- Drawing status DRAFT Revision - Author - Checked by - All plans within this document are reproduced from Ordnance Survey with permission of the control- ler of Her Majesty’s Stationary Office (C) Crown copyright. Unauthorised reproduction infringes Crown copyright and may lead to prosecution/civil proceedings. Licence No 100054593. Produced By: In Association With: 00 CONTENTS 01 - Introduction 02 - Site Context 03 - 1.1 - -- 2.1 - -- 3.1 - -- 01 Introduction Cystic Fibrosis Centre: University Hospital Llandough | Design and Access Staement 5 01 Introduction Cystic Fibrosis Centre: University Hospital Llandough STATEMENT PURPOSE This Design and Access Statement has been produced LEGISLATIVE CONTEXT to accompany a planningapplcation for the retention and 1. Explain the design principles and concepts that have been extension of the existing All Wales Cystic Fibrosis Centre As a result of the Planning (Wales) Act, Design and Access State- applied to the development; (AWCFC), at University Hospital Llandough. ments (DAS) are now required for the following types of develop- ment only: THE DEVELOPMENT 2. Demonstrate the steps taken to appraise the context of the development and how the design of the development takes All planning applications for “major” development except those The development proposed in the application includes: that context into account for mining operations; waste developments; relaxation of condi- • External works to improve the visual appearence of the tions (section ’73’ applications) and applications of a material 3. -

SCHEDULE B Public Cemeteries Cathays Cemetery, Fairoak Road

SCHEDULE B Public Cemeteries Cathays Cemetery, Fairoak Road, Cathays, CF24 4PY Landaff Cemetery, Cathedral Close, Llandaff, CF5 2AZ Llanishen Cemetery, Station Road, Llanishen, CF14 5AE Thornhill Crematorium, Thornhill Road, Thornhill, CF14 9UA Pantmawr Cemetery, Pantmawr Road, Pantmawr, CF14 7TD St Johns, Heol Isaf, Raydr, CF15 8DY Western Cemetery, Cowbridge Road West, Ely CF5 5TG As shown on the Schedule B Plans attached hereto. SCHEDULE C Enclosed Children’s Play Areas, Games Areas and Schools Childrens Play Areas The enclosed Children’s Play Areas shown on the Schedule C Plans attached hereto and listed below: Adamscroft Play Area, Adamscroft Place, Adamsdown Adamsdown Square, Adamsdown Sqaure, Adamsdown Anderson Fields, Constellation Street, Adamsdown Beaufort Square Open Space, Page Drive, Splott Beechley Drive Play Area, Beechley Drive, Fairwater Belmont Walk, Bute Street, Butetown Brewery Park, Nora Street, Adamsdown Britania Park, Harbour Drive, Butetown Bryn Glas Play Area, Thornhill Road, Thornhill Butterfield Park Play Area, Oakford Close, Pontrennau Caerleon Park, Willowbrook Drive, St Mellons Canal Parade, Dumballs Road, Butetown Canal Park, Dumballs Road, Butetown Cardiff Bay Barrage, Cargo Road, Docks Catherine Gardens, Uplands Road, Rumney Celtic Park, Silver Birch Close, Whitchurch Cemaes Park, Cemaes Crescent, Rumney Cemetery Park, Moira Terrace, Adamsdown Chapelwood Play Area, Chapelwood, Llanedeyrn Cogan Gardens Play Area, Senghennydd Road, Cathays Coleford Drive Open Space, Newent Road, St Mellons College Road Play -

Llantrithyd Report Web.Pdf

f r 1 1 1 I I Y Y r )' y }' ; I , r r r I \ \ \ I \ I \ q \ l j 11 /11 ) r)- ) \ \ ~\ <llllff 1/ , ~ \ \' f -/ ~ f 1 \ lItt _r __ ~ I """"- -< ~ """ I -<- \ """" ::........ ..... I -.::::-.... A RINGWORK IN SOUTH GLAMORGAN ....."'" -~ I ....,.~ ~~ I ......~"', - ~, "'" " I ~, .... ~, "'" ..... , "'" ....., :, ..., I f\ .".. ... 1 " I ,1 f \' ",.r ..... I, \' _1" t-"' ~ fYfrrYl1 -:~ - ". ~ "It- - 7"" I ~A ~""'''' l,f ~kk J..,.. IAA~~ J. ...... ... "'" I ... .".. ... .".. ~.,.. CARDIFF ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY ~: I ...... -. ""Y I r r r © Cardiff Archaeological Society and Contributors 1977 ISBN 0950584606 Published and printed by Cardiff Archaeological Society Frontispiece: Henry I Silver Penny (Cardiff Mint) Reproduced by permission of the National Museum of Wales Price: £3 plus 35 pence postage and packing Copies obtainable from: Cardiff Archaeological Society, clo Staff Tutor in Archaeology, Department of Extra-Mural Studies, University College, Cardiff, 38 and 40 Park Place, Cardiff CF1 3BB As the present Chairman of the Cardiff Archaeological Society, . , am very pleased to introduce this report and to dedicate it to all those who excavated at Llantrithyd or helped in other ways to further our knowledge of this important site. Ed. Jackson June, 1977. CONTENTS Foreword PART I THE SITE AND ITS EXCAVATION Introduction 2 The Excavations 3 An Interpretation of the Structures 16 PART I I THE FIN DS The Pottery 23 Edited by Peter Webster, B.A., M.Phil., F.S.A. Department of Extra-Mural Studies, University College, Cardiff. The Metalwork 46 By Ian H. Goodall, B,A. Royal Commission on Historical Monuments, York. The Coins 52 By Michael Dolley, M.R.I.A. Professor of Historical Numismatics, The Queen's University of Belfast. -

Courtenay Arthur Ralegh Radford

Courtenay Arthur Ralegh Radford Book or Report Section Published Version Creative Commons: Attribution 3.0 (CC-BY) Open Access Gilchrist, R. (2013) Courtenay Arthur Ralegh Radford. In: Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the British Academy, XII. British Academy, pp. 341-358. ISBN 9780197265512 Available at http://centaur.reading.ac.uk/35690/ It is advisable to refer to the publisher’s version if you intend to cite from the work. See Guidance on citing . Published version at: http://www.britac.ac.uk/memoirs/12.cfm Publisher: British Academy All outputs in CentAUR are protected by Intellectual Property Rights law, including copyright law. Copyright and IPR is retained by the creators or other copyright holders. Terms and conditions for use of this material are defined in the End User Agreement . www.reading.ac.uk/centaur CentAUR Central Archive at the University of Reading Reading’s research outputs online RALEGH RADFORD Pictured in 1957, in front of the ruins of the church at Glastonbury Abbey (Somerset). Reproduced with permission of English Heritage: NMR GLA/Pub/1/2. Courtenay Arthur Ralegh Radford 1900–1998 C. A. RALEGH RADFORD was one of the major figures of archaeology in the mid-twentieth century: his intellectual contribution to the discipline is rated by some as being comparable to giants such as Mortimer Wheeler, Christopher Hawkes and Gordon Childe.1 Radford is credited with help- ing to shape the field of medieval archaeology and in particular with inaug- urating study of the ‘Early Christian’ archaeology of western Britain. -

Cardiff | Penarth

18 Cardiff | Penarth (St Lukes Avenue) via Cogan, Penarth centre, Stanwell Rd 92 Cardiff | Penarth (St Lukes Avenue) via Bessemer Road, Cogan, Penarth centre, Stanwell Road 92B Cardiff | Penarth | Dinas Powys | Barry | Barry Waterfront via Cogan, Wordsworth Avenue, Murch, Cadoxton 93 Cardiff | Penarth | Sully | Barry | Barry Waterfront via Cogan, Stanwell Road, Cadoxton 94 Cardiff | Penarth | Sully | Barry | Barry Waterfront via Bessemer Road, Cogan, Stanwell Road, Cadoxton 94B on schooldays this bus continues to Colcot (Winston Square) via Barry Civic Office, Gladstone Road, Buttrills Road, Barry Road, Colcot Road and Winston Road school holidays only on school days journey runs direct from Baron’s Court to Merrie Harrier then via Redlands Road to Cefn Mably Lavernock Road continues to Highlight Park as route 98, you can stay on the bus. Mondays to Fridays route number 92 92B 94B 93 92B 94B 92 94 92B 93 92B 94 92 94 92B 93 92 94 92 94 92 city centre Wood Street JQ 0623 0649 0703 0714 0724 0737 0747 0757 0807 0817 0827 0837 0847 0857 0907 0917 0926 0936 0946 0956 1006 Bessemer Road x 0657 0712 x 0733 0746 x x 0816 x 0836 x x x 0916 x x x x x x Cogan Leisure Centre 0637 0704 0718 0730 0742 0755 0805 0815 0825 0835 0845 0855 0905 0915 0925 0935 0943 0953 1003 1013 1023 Penarth town centre Windsor Arcade 0641 0710 0724 0736 0748 0801 0811 0821 0831 0841 0849 0901 0911 0921 0931 0941 0949 0959 1009 1019 1029 Penarth Wordsworth Avenue 0740 x 0846 0947 Penarth Cornerswell Road x x x x 0806 x x x x x x x x x x x x x Cefn Mably Lavernock Road -

Llancadle CF62 3AQ £449,950 , , Llancadle CF62 3AQ

, , Llancadle CF62 3AQ £449,950 , , Llancadle CF62 3AQ A beautiful, high specification, converted barn set in the heart of Llancadle village with thoughtfully considered open plan family accommodation, renovated for the current owners in recent years. The accommodation offers living room with feature chimney and wood burner, kitchen‐dining room looking out over a sizeable rear garden, second multi‐purpose reception room, utility area and store room. The first floor offers master bedroom with en suite shower room, two further double bedrooms and a large family bathroom. Integral garage and off‐road parking. Westerly facing, enclosed garden and paved patio area. Llancadle is a small hamlet with an attractive mixer of houses. Local facilities are within easy reach in Llancarfan and St Athan, and both market towns of Cowbridge and Llantwit Major are within easy driving distance for more extensive facilities. The good local road network brings major centres within easy commuting distance and it is an easy drive to Cardiff Wales Airport and Cardiff city centre. Accommodation Landing Accessed via fantastic full turn staircase in oak with exposed pointed stonework and rope handrail. Ground Floor Double glazed velux window set into eaves. Mezzanine overlook. Vaulted ceiling. Inset chrome Entrance Lobby ceiling LED spotlighting. Oak flooring. Built in storage with chrome heated towel rail. Communicating Entered via oak front door with inset triple glazed square vision panel. To inset lobby with space for doors to all bedrooms and bathroom. shoes and cloaks. Varnished exposed beam work. Wooden clad ceiling. Pointed stonework. Oak Master Suite Bedroom One 13'6" x 10'6" (4.11 x 3.20) flooring. -

The Iron Age Tom Moore

The Iron Age Tom Moore INTRODUCfiON In the twenty years since Alan Saville's (1984) review of the Iron Age in Gloucestershire much has happened in Iron-Age archaeology, both in the region and beyond.1 Saville's paper marked an important point in Iron-Age studies in Gloucestershire and was matched by an increasing level of research both regionally and nationally. The mid 1980s saw a number of discussions of the Iron Age in the county, including those by Cunliffe (1984b) and Darvill (1987), whilst reviews were conducted for Avon (Burrow 1987) and Somerset (Cunliffe 1982). At the same time significant advances and developments in British Iron-Age studies as a whole had a direct impact on how the period was viewed in the region. Richard Hingley's (1984) examination of the Iron-Age landscapes of Oxfordshire suggested a division between more integrated unenclosed communities in the Upper Thames Valley and isolated enclosure communities on the Cotswold uplands, arguing for very different social systems in the two areas. In contrast, Barry Cunliffe' s model ( 1984a; 1991 ), based on his work at Danebury, Hampshire, suggested a hierarchical Iron-Age society centred on hillforts directly influencing how hillforts and social organisation in the Cotswolds have been understood (Darvill1987; Saville 1984). Together these studies have set the agenda for how the 1st millennium BC in the region is regarded and their influence can be felt in more recent syntheses (e.g. Clarke 1993). Since 1984, however, our perception of Iron-Age societies has been radically altered. In particular, the role of hillforts as central places at the top of a hierarchical settlement pattern has been substantially challenged (Hill 1996). -

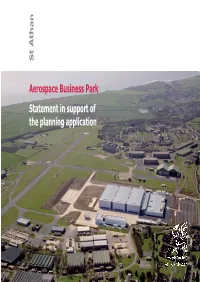

Aerospace Business Park Statement in Support of the Planning Application

St Athan Aerospace Business Park Statement in support of the planning application St Athan Aerospace Business Park Statement in support of the planning application incorporating Design and access statement May 2009 Department for the Economy and Transport Welsh Assembly Government QED Centre Main Avenue Treforest Industrial Estate Trefforest Rhondda Cynon Taf CF37 5YR Study team This statement has been prepared by a team comprising: Welsh Assembly Government Department for the Economy and Transport QED Centre, Main Avenue, Treforest Industrial Estate, Trefforest CF37 5YR WYG Planning & Design 21 Park Place, Cardiff CF10 3DQ Atkins Woodcote Grove, Ashley Road, Epsom, Surrey KT18 5BW Longcross Court, 47 Newport Road, Cardiff CF24 0AD Capita Symonds Tyˆˆ Gwent, Lake View, Llantarnam Park, Cwmbran, Torfaen NP44 3HR Kernon Countryside Consultants Brook Cottage, Purton Stoke, Swindon, Wiltshire SN5 4JE Mott MacDonald St Anne House, 20-26 Wellesley Road, Croydon, Surrey CR9 2UL Parsons Brinckerhoff 29 Cathedral Road, Cardiff CF11 9HA Walker Beak Mason Steepleton Lodge Barn, East Haddon, Northamptonshire NN6 8DU Study team 3 The site as existing 23 Contents Table of contents Location List of illustrations Land ownership Glossary of abbreviations Current uses Physical factors 1 Introduction 11 • Geology The applicant • Hydrogeology The agent • Ground conditions and Description of the proposed development contamination Type of planning application • Topography The application site • Built environment Planning application drawings Environmental -

1874 Marriages by Groom Glamorgan Gazette

Marriages by Groom taken from Glamorgan Gazette 1874 Groom's Groom's First Bride's Bride's First Date of Place of Marriage Other Information Date of Page Col Surname Name/s Surname Name/s Marriage Newspaper Bailey Alfred Davies Selina 30/05/1874 Register Office Groom coity Bride Coity 05/06/1874 2 3 Baker Samuel Williams Hannah 28/3/1874 Bettws Church Groom - Coytrahen 3/4/1874 2 6 Row, Bride of Shwt. Bevan Jenkin Marandaz Mary 17/12/1874 Margam Groom son of Evan 18/12/1874 2 5 Bevan Trebryn Both of Aberavon Bevan John Williams Ann 15/11/1874 Parish Church Pyle Both of Kenfig Hill 04/12/1874 2 5 Blamsy Arthur Wills Sarah 30/17/1874 Wesleyan chapel Groom of H M Dockyard 14/08/1874 2 6 Bridgend Portsmouth Bride Schoolmistress of Porthcawl Brodgen James Beete Mary Caroline 26/11/1874 Ewenny Abbey Groom Tondu House 27/11/1874 2 7 Church Bridgend and 101 Gloucester Place Portman Square London Bride Only daughter of Major J Picton Beete Brooke Thomas david Jones Mary Jane 28/04/1874 Gillingham Kent Groom 2nd son of 08/05/1874 2 5 James Brook Bridgend Bride elder daughter of John Jones Calderwood Marandaz 28/04/1874 Aberavon Groom Draper Bride 01/05/1874 2 7 Bridge House Aberavon Groom's Groom's First Bride's Bride's First Date of Place of Marriage Other Information Date of Page Col Surname Name/s Surname Name/s Marriage Newspaper Carhonell Francis R Ludlow Catherine 13/02/1874 Christchurch Clifton Groom from Usk 20/02/1874 2 4 Dorinda Monmouth - Bride was Daughter of Rev A R Ludlow Dimlands Castle Llantwit Major Carter Edmund Shepherd Mary Anne