Regional Rail: the European Dimension

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Commercial & Technical Evolution of the Ferry

THE COMMERCIAL & TECHNICAL EVOLUTION OF THE FERRY INDUSTRY 1948-1987 By William (Bill) Moses M.B.E. A thesis presented to the University of Greenwich in fulfilment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy October 2010 DECLARATION “I certify that this work has not been accepted in substance for any degree, and is not concurrently being submitted for any degree other than that of Doctor of Philosophy being studied at the University of Greenwich. I also declare that this work is the result of my own investigations except where otherwise identified by references and that I have not plagiarised another’s work”. ……………………………………………. William Trevor Moses Date: ………………………………. ……………………………………………… Professor Sarah Palmer Date: ………………………………. ……………………………………………… Professor Alastair Couper Date:……………………………. ii Acknowledgements There are a number of individuals that I am indebted to for their support and encouragement, but before mentioning some by name I would like to acknowledge and indeed dedicate this thesis to my late Mother and Father. Coming from a seafaring tradition it was perhaps no wonder that I would follow but not without hardship on the part of my parents as they struggled to raise the necessary funds for my books and officer cadet uniform. Their confidence and encouragement has since allowed me to achieve a great deal and I am only saddened by the fact that they are not here to share this latest and arguably most prestigious attainment. It is also appropriate to mention the ferry industry, made up on an intrepid band of individuals that I have been proud and privileged to work alongside for as many decades as covered by this thesis. -

Class 150/2 Diesel Multiple Unit

Class 150/2 Diesel Multiple Unit Contents How to install ................................................................................................................................................................................. 2 Technical information ................................................................................................................................................................. 3 Liveries .............................................................................................................................................................................................. 4 Cab guide ...................................................................................................................................................................................... 15 Keyboard controls ...................................................................................................................................................................... 16 Features .......................................................................................................................................................................................... 17 Global System for Mobile Communication-Railway (GSM-R) ............................................................................. 18 Registering .......................................................................................................................................................................... 18 Deregistering - Method 1 ............................................................................................................................................ -

UK's New Green Age: a Step Change in Transport Decarbonisation

THE UK’S NEW GREEN AGE A step change in transport decarbonisation January 2021 CONTENTS Alstom in the UK i The UK’s net zero imperative 1 Electrification 7 Hydrogen 15 High speed rail 26 A regional renaissance with green transport for all places 32 Conclusion 43 The New Green Age: a step change in transport decarbonisation ALSTOM IN THE UK Mobility by nature Alstom is a world leader in delivering sustainable and smart mobility systems, from high speed trains, regional and suburban trains, undergrounds (metros), trams and e-buses, to integrated systems, infrastructure, signalling and digital mobility. Alstom has been at the heart of the UK’s rail industry for over a century, building many of the UK’s rail vehicles, half of London’s Tube trains and delivering tram systems. A third of all rail journeys take place on Alstom trains including the iconic Pendolino trains on the West Coast Mainline, which carry 34 million passengers a year. Building on its history, Alstom continues to innovate. One of its most important projects is hydrogen trains—its Coradia iLint has been in service in Germany and Austria, and with Eversholt Rail, it has developed the ‘Breeze’ hydrogen train for the UK. Alstom’s state-of-the-art Transport Technology Centre in Widnes in the Liverpool City Region is its worldwide centre for train modernisation and is where the conversion of trains to hydrogen power will take place. It is among 12 other sites in the UK including Longsight in Manchester and Wembley in London. Across the world Alstom has developed, built and maintained transport systems including high speed rail in every continent that has high speed rail, and mass transit metros and trams schemes including in Nottingham and Dublin. -

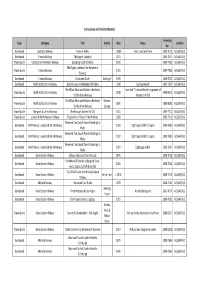

Publicity Material List

Early Guides and Publicity Material Inventory Type Company Title Author Date Notes Location No. Guidebook Cambrian Railway Tours in Wales c 1900 Front cover not there 2000-7019 ALS5/49/A/1 Guidebook Furness Railway The English Lakeland 1911 2000-7027 ALS5/49/A/1 Travel Guide Cambrian & Mid-Wales Railway Gossiping Guide to Wales 1870 1999-7701 ALS5/49/A/1 The English Lakeland: the Paradise of Travel Guide Furness Railway 1916 1999-7700 ALS5/49/A/1 Tourists Guidebook Furness Railway Illustrated Guide Golding, F 1905 2000-7032 ALS5/49/A/1 Guidebook North Staffordshire Railway Waterhouses and the Manifold Valley 1906 Card bookmark 2001-7197 ALS5/49/A/1 The Official Illustrated Guide to the North Inscribed "To Aman Mosley"; signature of Travel Guide North Staffordshire Railway 1908 1999-8072 ALS5/29/A/1 Staffordshire Railway chairman of NSR The Official Illustrated Guide to the North Moores, Travel Guide North Staffordshire Railway 1891 1999-8083 ALS5/49/A/1 Staffordshire Railway George Travel Guide Maryport & Carlisle Railway The Borough Guides: No 522 1911 1999-7712 ALS5/29/A/1 Travel Guide London & North Western Railway Programme of Tours in North Wales 1883 1999-7711 ALS5/29/A/1 Weekend, Ten Days & Tourist Bookings to Guidebook North Wales, Liverpool & Wirral Railway 1902 Eight page leaflet/ 3 copies 2000-7680 ALS5/49/A/1 Wales Weekend, Ten Days & Tourist Bookings to Guidebook North Wales, Liverpool & Wirral Railway 1902 Eight page leaflet/ 3 copies 2000-7681 ALS5/49/A/1 Wales Weekend, Ten Days & Tourist Bookings to Guidebook North Wales, -

Heljan 2020 Catalogue Posted

2020 UK MODEL RAILWAY PRODUCTS www.heljan.dk OO9 GAUGE Welcome …to the 2020 HELJAN UK catalogue. Over the coming pages we’ll introduce you to our superb range of British outline locomotives and rolling stock in OO9, OO and O gauge, covering many classic 6 steam, diesel and electric types. As well as new versions of existing PIN LYNTON & BARNSTAPLE RAILWAY products, we’ve got some exciting new announcements and updates DCC MANNING, WARDLE 2-6-2T READY on a few projects that you’ll see in shops in 2020/21. Class Profile: A trio of 2-6-2T locomotives built VERSION 1 - YEO, EXE & TAW NEM for the 1ft 11½in gauge Lynton & Barnstaple COUPLERS 9953 SR dark green E760 Exe New additions to the range since last year include the Railway in North Devon, joined by a fourth locomotive, Lew, in 1925 and used until the 9955 L&BR green Exe much-requested OO gauge Class 45s and retooled OO Class 47s, the SPRUNG railway closed in 1935. A replica locomotive, BUFFERS 9956 L&BR green Taw GWR ‘Collett Goods’, our updated O gauge Class 31s, 37s and 40s, the Lyd, is based at the Ffestiniog Railway in Wales. ubiquitous Mk1 CCT van and some old favourites such as the O gauge Built by: Manning, Wardle of Leeds VERSION 2 - LEW & LYD Number built: 4 9960 SR green E188 Lew Class 35 and split headcode Class 37. We’re also expanding our rolling Number series: Yeo, Exe & Taw (SR E759-761), stock range with a new family of early Mk2 coaches. -

Regional Railways: Access to a Car

COMMENT REGIONAL RAIL centres, where car commuting is increasingly unattractive and unacceptable. A mini london JONATHAN effect if you like. And facilitating the daily commute is a job BRAY that rail does well - even with (or perhaps despite of) Pacers. Away from the cities, the lines that were spared the Beeching blitz were often kept because road access was poor - and that fundamental hasn’t changed either. From the Esk Valley to the west Cumbrian coast people in rural areas need to get around too - particularly young people who don’t have Regional railways: access to a car. Combine this with Brits’ love of both trains and a grand day out and you have Destination Growth the success of lines like the Settle and Carlisle. Of course the regional railway network Despite low levels of investment, the regional rail sector has seen is not just an essay in enforced decrepitude astonishing levels of growth. What could it achieve if we back it? to a soundtrack of Pacers screeching and bouncing their way down jointed track. Where there has been investment we have seen I remember in the eighties, a day after a rail passengers per available train seating in the additional rocket boosters put on high levels strike, being on a dog-eared but dogged unit country (after London Overground). of background growth. The aforementioned on the Wharfedale Line into a wintery and What’s particularly remarkable is that this Wharfedale Line whose future looked so gloomy Leeds. The heaters competing with growth has been achieved in a sector where precarious in the eighties (‘be cheaper to send the draughty rattling windows to achieve some it’s common to have timetables where all that the passengers in chauffeur-driven cars’ I kind of fuggy equilibrium, squealing round changes is the date of issue. -

Conference Report

Railfuture Campaigners’ Conference – Stoke-on-Trent – 1st July 2006 Campaigning by the Railway Development Society Limited www.railfuture.org.uk CAMPAIGNERS’ CONFERENCE STOKE-ON-TRENT 1st JULY 2006 Sponsored by Grand Central Fraser Eagle www.grandcentralrail.com www.frasereagle.com CONFERENCE REPORT (FULLY UPDATED IN 2010) Written by Philip Bisatt (2010 Revisions by Jerry Alderson) Designed and Photos by Jerry Alderson The Railway Development Society Limited - A (non profit making) Company Limited by Guarantee Registered in England and Wales No 5011634 - Registered Office:- 12 Home Close, Bracebridge Heath, Lincoln LN4 2LP www.railfuture.org.uk Page 1 Railfuture Campaigners’ Conference – Stoke-on-Trent – 1st July 2006 CONFERENCE SPEAKERS Ian Yeowart Councillor Jean Edwards Andy Roden Managing Director Lord Mayor of Co -Chairman Grand Central City of Stoke-on-Trent Save Our Sleeper Ruth Annison Carl Henderson BEng.(Hons.), MSc, MIRTE, MSOE Caspar Lucas MEng CEng MIMechE Chairman Wensleydale Silvertip Design JM Parry & Associates Railway “BladeRunner” “Parry People Mover” Stuart Walker Jerry Alderson George Watson Railfuture Devon and Railfuture Vice Chairman MyTestTrack.com Cornwall and Conference Organiser Also, Manuel Cortes , the assistant general secretary of the T ransport Salaried Staffs’ Association (TSSA); Graham Nalty of Railfuture , speaking on High-Speed Rail; and Michael Wilmot who chaired “Question Time”. www.railfuture.org.uk Page 2 Railfuture Campaigners’ Conference – Stoke-on-Trent – 1st July 2006 FOREWARD BY CONFERENCE ORGANISER I hope that you enjoy reading this report about Railfuture ’s highly successful Campaigners’ Conference held in Stoke-on-Trent in 2006. A lot has happened in the four intervening years, with some very exciting developments, partly thanks to the hard work of campaigners including members of Railfuture . -

Best Methods of Railway Restructuring and Privatization

CFS Discussion Paper Series, Number 111 Best Methods of Railway Restructuring and Privatization Ron Kopicki Louis S. Thompson with Koichiro Fukui Murray King Jorge C. Kohon Jan-Eric Nilsson Brian Wadsworth For additional copies, please contact the CFS Information Office, tel: (202) 473-7594, fax: (202) 477-3045. ii BEST METHODS OF RAILWAY RESTRUCTURING AND PRIVATIZATION TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS X ACKOWLEDGMENTS XII FOREWORD XIII EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 1. Introduction 1 2. Case Study Experiences 2 3. Alternative Railway Structures 3 4. Alternative Asset Restructuring Mechanisms 4 5. Design of Intermediate Institutional Mechanisms 5 6. Managing the Railway Restructuring Process 6 CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION 9 1. Scope of the Study 9 2. Importance of Railway Restructuring 10 3. Economic Features of Railways 10 4. “Best Methods” Approach 12 5. Railway Case Studies 13 6. Organization of the Study 17 CHAPTER TWO: STRUCTURAL OPTIONS 19 1. Introduction 19 2. Restructuring a Railway: General Design Considerations 19 3. Asset Restructuring: Structural Forms 21 4. Asset Restructuring: Mechanisms 24 5. Liability Restructuring 29 6. Work Force Restructuring 32 7. Management Restructuring 36 8. Strategic Refocusing 37 9. Best Methods 39 CHAPTER THREE: INTERMEDIATE INSTITUTIONAL MECHANISMS 41 1. Introduction 41 2. The Need for Intermediation 41 3. Relationship between the Intermediary and the Railway 43 4. Essential Functions Performed by Restructuring Intermediaries 44 5. Larger Transport Policy Context and the Need to Rebalance Policy Principles 48 6. Alternative Organizational Forms 49 7. Prerequisites for Effective Intermediation Operations 52 8. Best Methods 52 CHAPTER FOUR: MANAGING THE RESTRUCTURING PROCESS 55 1. Introduction 55 2. -

Railway Passenger Companies

The Railway Passenger Companies Research Paper 97/72 30 May 1997 This Research Paper lists the names and addresses of the train operating companies and the companies who acquired their franchises, and gives some background detail about the franchise award. It is designed to accompany Library Research Paper 97/71, The Privatised Railway, which describes the legal framework. Fiona Poole Business & Transport Section House of Commons Library Library Research Papers are compiled for the benefit of Members of Parliament and their personal staff. Authors are available to discuss the contents of these papers with Members and their staff but cannot advise members of the general public. Contents Page A Background 5 B The Train Operating Companies Anglia Railways 7 Cardiff Railway 9 Central trains 11 Chiltern 14 Connex South Central 16 Connex South Eastern 18 CrossCountry Trains 20 Gatwick Express 22 Great Eastern 24 Great North Eastern 26 Great Western 28 Island Rail 30 LTS Rail 32 Merseyrail Electrics 34 Midland Main Line 36 North London Railways 38 North West Regional Railways 40 Regional Railways North East 42 ScotRail 45 South Wales and West 48 South West Trains 50 Thames Trains 52 Thameslink 54 West Anglia Great Northern 56 West Coast Trains 58 C The Franchisees of the Passenger Rail Operations 60 D Selected Bibliography 64 Abbreviations ATOC Association of Train Operating Companies BR British Rail CRUCC Central Rail Users' Consultative Committee DMU Diesel Multiple Unit EPS European Passenger Services Ltd EU European Union GNER Great North -

Options for Regional Rail Report

Options for Regional Rail A review of ways to improve Britain’s regional rail services October 2013 1 Author contacts This report was researched and written by: Dr Ian Taylor Dr Lynn Sloman Transport for Quality of Life Ltd www.transportforqualityoflife.com [email protected] ©Copyright Transport for Quality of Life Ltd. All rights reserved. Disclaimers Statements in this report reflect the authors’ views based on the available data and should not be taken as official pteg policy. Acknowledgements The authors are most grateful to Pedro Abrantes, economist at pteg , for access to his researches into rail company financial data and patient explanations of its implications. Terminology and scope This report covers options relevant to Scotland and Wales as well as the English regions, and where the term regional rail is used it should be taken to include the rail services within the devolved nations. This terminology is rather insensitive but does accord with the Office of Rail Regulation definition of regional train services and with the European Union use of regional. Similarly, the term ‘regional transport authority’ is adopted to cover the different public bodies with varying degrees of authority over regional rail services, in particular the governments of the devolved nations and the passenger transport executives, but also to include similar public bodies that might arise in other regions of England in order to take on devolved responsibilities for regional rail. The options presented for regional rail in this report are not, however, intended to extend to Northern Ireland, which has a completely separate rail system, physically unconnected to the rest of Britain’s rail network, although with important rail links to Eire, and with track and trains within public ownership and already under entirely autonomous management by the Northern Ireland Executive. -

Class 47 Network Southeast Add-On

Class 47 Network Southeast Add-On 1 BACKGROUND ......................................................................................... 2 Network Southeast .............................................................................................................. 2 2 ROLLING STOCK ...................................................................................... 3 2.1 Class 47 NetworkSoutheast ............................................................................................. 3 2.2 Class 47 NSE revised ...................................................................................................... 3 2.3 Mk2 A Coaches .............................................................................................................. 4 3 SCENARIOS ............................................................................................. 5 3.1 Free Roam: Old Oak Common .......................................................................................... 5 3.2 Heading Southeast ......................................................................................................... 5 3.3 Slow from Slough........................................................................................................... 5 3.4 Twisted Rush Hour ......................................................................................................... 5 4 USING NETWORK SOUTHEAST IN CUSTOM SCENARIOS ............................ 6 Version 1.0 RailSimulator.com 2 RailWorks – Network SouthEast 1 Background Network Southeast Network -

Rail Privatisation: the Practice – an Analysis of Seven Case Studies

This is a repository copy of Rail Privatisation: The Practice – An Analysis of Seven Case Studies. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/2158/ Monograph: Shires, J.D., Preston, J.M., Nash, C.A. et al. (1 more author) (1994) Rail Privatisation: The Practice – An Analysis of Seven Case Studies. Working Paper. Institute of Transport Studies, University of Leeds , Leeds, UK. Working Paper 420 Reuse See Attached Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ White Rose Research Online http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Institute of Transport Studies University of Leeds This is an ITS Working Paper produced and published by the University of Leeds. ITS Working Papers are intended to provide information and encourage discussion on a topic in advance of formal publication. They represent only the views of the authors, and do not necessarily reflect the views or approval of the sponsors. White Rose Repository URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/2158/ Published paper Shires, J.D., Preston, J.M., Nash, C.A., Wardman, M. (1994) Rail Privatisation: The Practice – An Analysis of Seven Case Studies. Institute of Transport Studies, University of Leeds. Working Paper 420 White Rose Consortium ePrints Repository [email protected] UNIVERSITY OF LEEDS Institute for Transport Studies ITS Working Paper 420 ISSN 0141-h'(l?l July 1994 RAIL PRIVATISATION: THE PRACTICE - AN ANALYSIS OF SEVEN CASE STUDIES J D Shires J M Preston C A Nash M Wardman This paper was undertaken as part of an ESRC project on the effects of rail privntisrrtion.