Hindu Chaplaincy in US Higher Education Summary and Guidelines

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Brahma Sutra

BRAHMA SUTRA CHAPTER 1 1st Pada 1st Adikaranam to 11th Adhikaranam Sutra 1 to 31 INDEX S. No. Topic Pages Topic No Sutra No Summary 5 Introduction of Brahma Sutra 6 1 Jijnasa adhikaranam 1 a) Sutra 1 103 1 1 2 Janmady adhikaranam 2 a) Sutra 2 132 2 2 3 Sastrayonitv adhikaranam 3 a) Sutra 3 133 3 3 4 Samanvay adhikaranam 4 a) Sutra 4 204 4 4 5 Ikshatyadyadhikaranam: (Sutras 5-11) 5 a) Sutra 5 324 5 5 b) Sutra 6 353 5 6 c) Sutra 7 357 5 7 d) Sutra 8 362 5 8 e) Sutra 9 369 5 9 f) Sutra 10 372 5 10 g) Sutra 11 376 5 11 2 S. No. Topic Pages Topic No Sutra No 6 Anandamayadhikaranam: (Sutras 12-19) 6 a) Sutra 12 382 6 12 b) Sutra 13 394 6 13 c) Sutra 14 397 6 14 d) Sutra 15 407 6 15 e) Sutra 16 411 6 16 f) Sutra 17 414 6 17 g) Sutra 18 416 6 18 h) Sutra 19 425 6 19 7 Antaradhikaranam: (Sutras 20-21) 7 a) Sutra 20 436 7 20 b) Sutra 21 448 7 21 8 Akasadhikaranam : 8 a) Sutra 22 460 8 22 9 Pranadhikaranam : 9 a) Sutra 23 472 9 23 3 S. No. Topic Pages Topic No Sutra No 10 Jyotischaranadhikaranam : (Sutras 24-27) 10 a) Sutra 24 486 10 24 b) Sutra 25 508 10 25 c) Sutra 26 513 10 26 d) Sutra 27 517 10 27 11 Pratardanadhikaranam: (Sutras 28-31) 11 a) Sutra 28 526 11 28 b) Sutra 29 538 11 29 c) Sutra 30 546 11 30 d) Sutra 31 558 11 31 4 SUMMARY Brahma Sutra Bhasyam Topics - 191 Chapter – 1 Chapter – 2 Chapter – 3 Chapter – 4 Samanvaya – Avirodha – non – Sadhana – spiritual reconciliation through Phala – result contradiction practice proper interpretation Topics - 39 Topics - 47 Topics - 67 Topics 38 Sections Topics Sections Topics Sections Topics Sections Topics 1 11 1 13 1 06 1 14 2 07 2 08 2 08 2 11 3 13 3 17 3 36 3 06 4 08 4 09 4 17 4 07 5 Lecture – 01 Puja: • Gratitude to lord for completion of Upanishad course (last Chandogya Upanishad + Brihadaranyaka Upanishad). -

Orleans Yoga LIT A5 Brochure PRINT.Qxp Layout 1

Yoga LIT Yoga Life Immersion Training For Sivananda teachers at the Ashram de Yoga Sivananda, Loire Valley, France Tel: +33 (0)2 38 91 88 82 • sivanandaorleans.org • sivananda.eu 2 www.sivanandaorleans.org Tel: +33 (0)2 38 91 88 82 3 You have taken the Sivananda Teachers’ Training Course, Yoga LIT – Yoga Life Immersion Training maybe the Advanced Teachers’ Training Course and wonder For Sivananda teachers what is the next step for you to move further in your practice and spiritual life? The Ashram de Yoga Sivananda in Orleans is offering you “True education will make you a messenger of a new possibility to expand your knowledge and yoga a new hope, a new vision and a new culture” experience. – Swami Sivananda “Your destiny is in your hands. That is why you The Yoga LIT experience are here, to learn self-discipline, to gain the A new six-month guided residential programme of study, practice greatest knowledge: mind alone is the cause and service. of your bondage, and mind alone can become the cause of your liberation.” You will immerse yourself in a yogic lifestyle, expand your knowledge, develop your teaching skills and discover your hidden talents while – Swami Vishnudevananda living in the inspiring and protected atmosphere of a spiritual community. Yoga LIT is the first step to developing a Yoga University at the Ashram de Yoga Sivananda for the long term study of yogic and vedic sciences in the Gurukula tradition (the ancient yogic system of learning). Swami Durgananda Swami Sivadasananda Swami Kailasananda Yoga Acharya Yoga Acharya Yoga Acharya 4 www.sivanandaorleans.org Tel: +33 (0)2 38 91 88 82 5 Yoga LIT gives you a chance to: • Deepen your Yoga experience after having taken courses such as TTC, ATTC and Sadhana Intensive. -

Shiva-Vishnu Temple

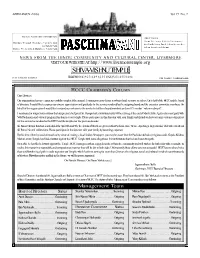

APR-MAY-JUN-2006 Vol.19 No.2 PLEASE NOTE THE SCHEDULES DIRECTIONS From Freeway 580 in Livermore: Monday Through Thursday: 9 am to 12 noon Exit North Vasco Road, left on Scenic Ave, and 6 pm to 8 pm Left on Arrowhead Avenue F r i d a y, Weekends & Holidays: 9 am to 8 pm NEWS FROM THE HINDU COMMUNITY AND CULTURAL CENTER, LIVERMORE VISIT OUR WEB SITE AT http://www.livermoretemple.org SHIVA-VISHNU TEMPLE OM NAMAH SHIVAYA TELEPHONE (925) 449-6255 FAX (925) 455-0404 OM NAMO NARAYA N AYA HCCC CH A I R M A N ’S CO L U M N Dear Devotees: Our organization has once again successfully completed the annual elections process to choose new board and executive members. On behalf of the HCCC and the board of directors, I would like to express our sincere appreciation and gratitude for the services rendered by the outgoing board and the executive committee members. On behalf of the organization I would like to extend our welcome to the newly elected three board members and one EC member “welcome aboard”. I mentioned in my previous column that our present chief priest Sri. Rompicharla Srinivasacharlu will be retiring at the end of March 2006. A gala retirement party with Veda Pathanam and cultural program function is at our temple. Please participate in this function with your family and friends to show our appreciation to this priest for the services he rendered to the HCCC and the temple over the past two decades. Sri Rama Navami function is scheduled for April 6th and 9th, the details of which are given in this Pachima Vani. -

Cultural Embedding of Environmental Consciousness and Conservation

Volume 2 Issue 4 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF HUMANITIES AND March 2016 CULTURAL STUDIES ISSN 2356-5926 Cultural Embedding of Environmental Consciousness and Conservation Minakshi Maharaj Department of Language and Literature Fiji National University, Fiji [email protected] Abstract The practices of a community express its worldview, values, belief systems and attitudes. This paper explains the central concept in Hinduism pertaining to the relationship between the creator, humans and nature. It examines how these Hindu beliefs have been translated into everyday rituals and practices that express the relationship of interdependence between humans and their natural environment. These rituals, beliefs and practices instill Hindu values pertaining to the earth, natural phenomena and human beings. Thus they encourage environmental sensitivity and promote conservation. Keywords: Hindu beliefs, practices, environmental concern. http://www.ijhcs.com/index.php/ijhcs/index Page 749 Volume 2 Issue 4 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF HUMANITIES AND March 2016 CULTURAL STUDIES ISSN 2356-5926 नि셍विो 셍鵍यते 핍याघ्रो नि핍यावघ्रो नि饍यते 셍िम ् | तमा饍핍याघ्रो 셍िं रक्षेत ्셍िं 핍याघ्रं च पालयेत ्|| Without the forest, the tiger cannot survive. Without the tiger in the forest, the forest will get destroyed by people. Hence the tiger must protect the forest and forest must protect the tiger (and other animals) (Sanskrit Proverb, 2015) Hindu concepts of nature Environmental concern and protection are embedded in the Hindu tradition because of the concept of the fundamental unity and interdependence of all creation including humans, flora and fauna. These religious concepts are translated into daily rituals and practices. -

Yoga Certification Board SYLLABUS Therapeutic Yoga Consultant

Yoga Certification Board Ministry of Ayush, Govt. of India Website- www.yogacertificationboard.nic.in SYLLABUS Therapeutic Yoga Consultant YOG Certification Board Syllabus for Therapeutic Yoga Consultant (ThYC) 1. Name of the Certification: Therapeutic Yoga Consultant (ThYC) 2. Requirement/ Eligibility: a. Medical Professional or Masters in Yoga. (For Yoga professional medical knowledge is required and vice versa) 3. Brief Role Description: Can practice Yoga for treatment of diseases in medical setups or independently. He should be a registered medical practitioner in any stream with Yoga Therapy. 4. Minimum age: No age limit 5. Personal Attributes: The job requires individual to have good communication skills, time management and ability to understand the body language of the trainees. Self discipline confidence, maturity, patience, compassion, active listening, empathetic, and proficiency in language. 6. Credit points for certificate: 92 credits 7. Duration of course: Not less than 1600 hours (Contact program for 100 hrs. to be conducted on Anatomy, Physiology ) 8. Mark Distribution: Total Marks: 200 (Theory: 140+Practical: 60) Unit No. Unit Name Marks 1. Therapeutic Approach of Yoga Therapy in 35 Classical Yogic Texts Theory 2. Principals of Yoga Therapy 35 3. Anatomy, Physiology and Psychology Foundations 35 4. Yogic Concept for Management of Diseases 35 Total 140 Unit No. Practical Work Marks 1. Demonstration Skills 10 2. Teaching Skills 10 Practical 3. Evaluation Skills 15 4. Application of knowledge 15 5. Field Experience 10 Total 60 1 YOG Certification Board Theory Syllabus UNIT 1 Therapeutic Approch of Yoga Therapy in Classical Yogic Texts 1.1 BhagavadGita as a Therapy 1.1.1 Definitions of Yoga in Bhagavadgita and their relevance in Yoga therapy. -

Yoga: Our Heritage

2nd INTERNATIONAL DAY OF YOGA 2016 Bihar School of Yoga, Munger, presents Yoga: Our Heritage On the occasion of the second Interna tional Day of Yoga we offer our good wishes to all those who have been inspired by the tradition and the tea chings of yoga. It is a day to honour the ancient science of yoga, a science of transformation and spiritual evolution perfected and handed down by the ancient sages and seers of humanity over the ages – our real spiritual heritage. A vision realized The International Day of Yoga represents the inter national recog nition that yoga has gained as a holistic approach to physical wellbeing, mental peace and emotional balance. Across the globe, millions of people have embraced yoga to attain health and harmony, and to explore their inner potential. The acceptance of the International Day of Yoga, with a record consensus vote at the United Nations General Assembly, was a historic moment for India. The openness and enthusiasm with which the world community has embraced yoga and the collective good will that yoga has inspired, is a matter of great happiness and joy which all can share. This day is of special importance for the Satyananda Yoga tradition, as it marks the fruition of the vakya, the vision and the prophecy of Swami Satyananda Saraswati, when in 1963 he proclaimed: “Yoga will emerge as a mighty world culture and change the course of world events.” 1 First IDY in Munger, the ‘City of Yoga’ On the first International Day of Yoga celebrated on 21st June 2015, thou sands stepped out of their homes enthu siastically and gathered at prominent locations all over the whole world to express their solidarity towards yoga. -

A Sadhana, Lifestyle and Culture

3rd INTERNATIONAL DAY OF YOGA 2017 Bihar School of Yoga, Munger, presents Yoga: A sadhana, lifestyle and culture On the occasion of the third International Day of Yoga, we extend our greetings to all yoga aspirants. This day is of special importance for the Satyananda Yoga tradition, as it marks the fruition of the vision and the prophecy of Swami Satyananda Saraswati, when in 1963 he proclaimed: “Yoga will emerge as a mighty world culture and change the course of world events.” Since 2015 the International Day of Yoga has become an opportunity for people from all parts of the globe and all walks of life to come together in the spirit of yoga and reaffirm their commitment to this ancient science. The Bihar School of Yoga has wholeheartedly supported this global expression of goodwill towards yoga by promoting programs that inspire aspirants to deepen their experience of yoga and adopt it not merely as a physical practice but as a progressive sadhana, a harmonious lifestyle, and a holistic, humanitarian culture. Progression of yoga Yoga initially begins as a practice for an aspirant, a set of techniques practised to fulfil a personal need. Once the need is met, one’s association with yoga dwindles as well. This indicates a superficial connection with the vidya of yoga. However, in order to deepen one’s experience of yoga and reap greater gains, one’s personal whims and goals need to be set aside and one needs to strive towards the aims and aspirations set 1 by yoga itself, with an attitude of seriousness, sincer ity and commitment. -

Symbols and Talismans

Symbols and Talismans By Maha Yogi Paramahamsa Dr.Rupnathji As you set up your divination area, it helps to have objects that carry special symbolism for you. Talismans are symbolic objects that contain power that you confer upon them. How does that work? Well, take the example of the bogeyman. The bogeyman is created by the child's imagination. Even though no bogeyman has ever had any special powers, every child has experienced the terror of her own private bogeyman—a made-up creature that never quite looks the same to any child around the world. Sometimes children even come up with resourceful ways to rid themselves of this demon—by keeping a night-light on, barring the closet door, doing a quick check under the bed, and so on. By believing in the bogeyman, the children make the creature real and give it power over them. Channeling Energy Through Symbols : If you give something power, it becomes the symbol you want it to represent. If there is a particular symbol that gives you comfort or makes you feel stronger, keep it near to you. Though certain symbols have universal meaning, only those that feed your positive energy and sharpen your instincts will make a difference. Positive energy needs channeling points. This is what your symbols are used for. Successful divination requires that you harmonize with the energy around you, and a talisman can help you do that because it concentrates the vibrations of the energy you are trying to focus on. In turn, you wind up on the same frequencyDR.RUPNATHJI( level as the positive DR.RUPAK energy you've NATH assigned ) to your symbol. -

ESSENCE of TAITTIRIYA ARANYAKA Part 1

ESSENCE OF TAITTIRIYA ARANYAKA Part 1 ( KRISHNA YAJURVEDA) BY V. D. N. RAO 1 Compiled, composed and interpreted by V.D.N.Rao, former General Manager, India Trade Promotion Organisation, Pragati Maidan, New Delhi, Ministry of Commerce, Govt. of India, now at Chennai. Other Scripts by the same Author: Essence of Puranas:-Maha Bhagavata, Vishnu Purana, Matsya Purana, Varaha Purana, Kurma Purana, Vamana Purana, Narada Purana, Padma Purana; Shiva Purana, Linga Purana, Skanda Purana, Markandeya Purana, Devi Bhagavata;Brahma Purana, Brahma Vaivarta Purana, Agni Purana, Bhavishya Purana, Nilamata Purana; Shri Kamakshi Vilasa Dwadasha Divya Sahasranaama: a) Devi Chaturvidha Sahasra naama: Lakshmi, Lalitha, Saraswati, Gayatri; b) Chaturvidha Shiva Sahasra naama-Linga-Shiva-Brahma Puranas and Maha Bhagavata; c) Trividha Vishnu and Yugala Radha-Krishna Sahasra naama-Padma-Skanda- Maha Bharata and Narada Purana. Stotra Kavacha- A Shield of Prayers -Purana Saaraamsha; Select Stories from Puranas Essence of Dharma Sindhu - Dharma Bindu - Shiva Sahasra Lingarchana-Essence of Paraashara Smriti Essence of Pradhana Tirtha Mahima Essence of Upanishads : Brihadaranyaka , Katha, Tittiriya, Isha, Svetashwara of Yajur Veda- Chhandogya and Kena of Saama Veda-Atreya and Kausheetaki of Rig Veda-Mundaka, Mandukya and Prashna of Atharva Veda ; Also ‘Upanishad Saaraamsa’ (Quintessence of Upanishads) Essence of Virat Parva of Maha Bharata- Essence of Bharat Yatra Smriti Essence of Brahma Sutras Essence of Sankhya Parijnaana- Also Essence of Knowledge of Numbers Essence -

Hindu Deities

Hindu Deities Tridevi: Trimurti / The three energies • Saraswati • Brahma - creative force; generator • Lakshmi • Shiva - transformative; destroyer • Parvati • Vishnu - sustainer/preserver; operator Saraswati: Dynamic knowledge, wisdom, music, language That which flows, or watery, or elegant; the flow of creativity Saraswati is often portrayed as dressed in white while sitting on a white lotus (representing purity, pure knowledge, wisdom and mind). She has four arms one holding a manuscript or book (symbolizing textual knowledge). A Japa Mala or rosary in another (signifying knowledge from spiritual practice). In the other two, she holds a vina, a musical instrument, signifying the gift of music and poetry. She often has a swan (hamsa) with her as her vehicle because the swan when given milk and water can separate the two and will choose only milk meaning it can differentiate from good and evil. Saraswati represents the four functions of the mind/ personalty: manas (sensory/processing mind, low level), buddhi (knows, decides,intellect), chitta (subconcious mind, stored impressions, samskaras), and ahankara (I-maker, ego, asmita, what you identify with). She is wife and (sometimes) daughter to Brahma. “Saraswati gives the essence of one’s self. She provides us with the mundane and spiritual knowledge of our lives. She is a representation of the science of life, or the Vedanta, which attempts to unravel the essentials of human existence and the universe concealed within. She points to the ultimate aim of human life which is to realize the true nature of the self even if it requires an enormous amount of determination, perseverance and patience. The knowledge that Saraswati renders through continual worship, devotion and discipline is one of an integral vision in which both temporal and spiritual levels of study are meditated upon, practiced and developed. -

Vedic-Shanti-Mantras.Pdf

Stillpoint Yoga London | Vedic Shanti Mantras om I worship the guru’s lotus feet, awakening the Vande gurunaam chaaranara vinde / happiness of the self revealed. Beyond sandar shita swaatma sukhava bhode / comparison, acting like the jungle physician to nishrey yase jaangalika yamane / pacify delusion from the poison of existence. samsara haala hala moha shantye // to patanjali, an incarnation of adisesa, white in Abahu purusha karam / color with 1000 radiant heads (in his form as shankha chakraasi dharinam / sahasra the divine serpent, ananta), human in form shirasam shvetam / pranamaami below the shoulders holding a sword patanjalim / (discrimination), a wheel of fire (discus of light, om representing infinite time) and a conch (divine sound) – to him, I prostrate. om saha naa vavatu / may Braham protect us both together. saha nau bhunaktu / may he nourish us both together. saha viiryam / may we both work together with great energy. Karavaa vahai / may our study be vigorous and effective. may tejas vinaa vadhiita mastu ma / we never hate each other. Vidvishaa vahaihi // may peace, physical, mental and spiritual, be on us forever. om shantih shantih shantihi om peace peace peace. om shan no mitra shan varunaha / may mitra (the sun who controls the prana) shan no bhavat varyama / grant us peace; may Varuna (the lord of the shan na indro bruha spatihi / night and controller of the apana) grant peace shan no Vishnu ruru kramaha / to us; may aryaman (the principle of chivalry) namo bramhane / be propitious to us; may Indra (the cosmic namaste vaayo / mind) and Brihaspati (the principle of wisdom) grant us peace; may Vishnu of great strides twameva pratyaksham bramhaasi / (the supreme omnipresent godhead) be twameva pratyaksham bramha propitious to us. -

Shanti Mantra

Shanti Mantra From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Jump to: navigation, search This article contains Indic text. Without proper rendering support, you may see question marks or boxes, misplaced vowels or missing conjuncts instead of Indic text. An article related to Hinduism Hindu History Deities[show] Scriptures[show] Practices[show] Philosophers[show] Other topics[show] v t e The Shanti Mantras or "Peace Mantras" are Hindu prayers for Peace (Shanti) from the Vedas. Generally they are recited at the beginning and end of religious rituals and discourses. Shanti Mantras are found in Upanishads, where they are invoked in the beginning of some topics of Upanishads. They are supposed to calm the mind of the reciter and environment around him/her. Reciting them is also believed to be removing any obstacles for the task being started. Shanti Mantras always end with three utterances of word "Shanti" which means "Peace". The Reason for uttering three times is for calming and removing obstacles in three realms which are: "Physical" or Adhi-Bhautika, "Divine" or Adhi-Daivika and "Internal" or Adhyaatmika According to the scriptures of Hinduism sources of obstacles and troubles are in these three realms. Physical or Adhi-Bhautika realm can be source of troubles/obstacles coming from external world, such as from wild animals, people, natural calamities etc. Divine or Adhi-Daivika realm can be source of troubles/obstacles coming from extra-sensory world of spirits, ghosts, deities, demigods/angels etc. Internal or Adhyaatmika realm is source of troubles/obstacles arising out of one's own body and mind, such as pain, diseases, laziness, absent-mindedness etc.