Constantine and His Revolution

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Waters of Rome Journal

TIBER RIVER BRIDGES AND THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE ANCIENT CITY OF ROME Rabun Taylor [email protected] Introduction arly Rome is usually interpreted as a little ring of hilltop urban area, but also the everyday and long-term movements of E strongholds surrounding the valley that is today the Forum. populations. Much of the subsequent commentary is founded But Rome has also been, from the very beginnings, a riverside upon published research, both by myself and by others.2 community. No one doubts that the Tiber River introduced a Functionally, the bridges in Rome over the Tiber were commercial and strategic dimension to life in Rome: towns on of four types. A very few — perhaps only one permanent bridge navigable rivers, especially if they are near the river’s mouth, — were private or quasi-private, and served the purposes of enjoy obvious advantages. But access to and control of river their owners as well as the public. ThePons Agrippae, discussed traffic is only one aspect of riparian power and responsibility. below, may fall into this category; we are even told of a case in This was not just a river town; it presided over the junction of the late Republic in which a special bridge was built across the a river and a highway. Adding to its importance is the fact that Tiber in order to provide access to the Transtiberine tomb of the river was a political and military boundary between Etruria the deceased during the funeral.3 The second type (Pons Fabri- and Latium, two cultural domains, which in early times were cius, Pons Cestius, Pons Neronianus, Pons Aelius, Pons Aure- often at war. -

Ba-English.Pdf

CLARION UNIVERSITY DEGREE: B.A. English College of Arts & Sciences REVISED CHECKSHEET with NEW INQ PLACEMENT Name Transfer: * Clarion ID ** Entrance Date CUP: _____ _____ _____ _____ _____ _____ _____ _____ Program Entry Date _____ _____ _____ _____ _____ _____ _____ _____ Advisor _____ _____ _____ _____ _____ _____ _____ _____ *************************************************************************************************************************************** GENERAL EDUCATION REQUIREMENTS - 48 CREDITS V. REQUIREMENT for the B.A. DEGREE (see note #1 on back of sheet) Foreign Language competency or coursework1: CR. GR. I. LIBERAL EDUCATION SKILLS - 12 CREDITS CR. GR. : A. English Composition (3 credits) : ENGL 111: College Writing II ____ ____ : : B. Mathematics Requirement (3 credits) : VI. REQUIREMENTS IN MAJOR (42 CREDITS) 1. CORE REQUIREMENTS (15 credits) C. Credits to total 12 in Category I, selected from at least two of the following: Academic Enrichment, MMAJ 140 or 340, ENGL 199: Introduction to English Studies ____ ____ Computer Information Science, CSD 465, Elementary Foreign ENGL 202: Reading & Writing: _______________ ____ ____ Language, English Composition, HON 128, INQ 100, Logic, ENGL 282: Intro to the English Language ____ ____ & Mathematics ENGL 303: Focus Studies: ___________________ ____ ____ ENGL 404: Advanced English Studies ____ ____ 2. BREADTH OF KNOWLEDGE2 (12 credits) : II. LIBERAL KNOWLEDGE - 27 CREDITS Two 200-level writing courses A. Physical & Biological Science (9 credits) selected from at least two of the following: Biology, Chemistry, Earth Sci., ENVR275, ENGL ____: ______________________________ ____ ____ GS411, HON230, Mathematics, Phys. Sci., & Physics. ENGL ____: ______________________________ ____ ____ : : Two 200-level literature courses : ENGL ____: ______________________________ ____ ____ B. Social & Behavioral Science (9 credits) selected from at least two ENGL ____: ______________________________ ____ ____ of the following: Anthropology, CSD125, CSD 257, Economics, Geography, GS 140, History, HON240, NURS320, Pol. -

A MESAMBRIAN COIN of GETA Luchevar Lazarov Unlike The

TALANTA XXXIV-XXXV (2002-2003) A MESAMBRIAN COIN OF GETA Luchevar Lazarov Unlike the abundant production during the Classical and Hellenistic periods, the activity of the mint at Mesambria Pontica in Roman times was relatively 1 limited . Until now, the following mints are known: Hadrian (117-138 AD), Septimius Severus (193-211 AD), Caracalla (198-217 AD), Gordian III (238- 244 AD), Philip the Arab (244-249 AD), Philip II (247-249 AD) and the empress Acilia Severa, wife of the emperor Elagabalus (218-222 AD) (Karayotov 1992, 49-66). Recently, a Mesambrian coin from the time of the emperor Augustus (27 BC - 14 AD) was found in the private collection of N. Mitkov from Provadija (NE 2 Bulgaria) , showing the beginning of the Roman mint in the city (Karayotov 1994, 20). In this present note, a Roman Mesambrian coin of the emperor Geta (209-212 AD) is presented, testifying that in the beginning of the 3rd century AD, also coins bearing the name of this son of Septimius Severus were minted in Mesambria. AUKPÇEP Obv.: / GETAC, showing a bust of Geta with laurel wreath and wearinMgEaÇcAuMiraBssR anId pAaNluPdaN mentum (Fig. 1). Rev.: / / , showing a naked Hermes with a purse in his right and a caduceus in his left hand. The face is turned to the left (Fig. 2) > AE; — ; D: 23-24 mm. Taking the size of this coin in account, it probably belongs to nominal III (Schönert-Geiss 1990, 23-99). 1 On Mesambrian coinage of the pre-Roman period, see: Karayotov 1992, Karayotov 1994, Topalov 1995. 2 I would like to thank mr. -

Dell Vostro 270S Owner's Manual

Dell Vostro 270s Owner’s Manual Regulatory Model: D06S Regulatory Type: D06S001 Notes, Cautions, and Warnings NOTE: A NOTE indicates important information that helps you make better use of your computer. CAUTION: A CAUTION indicates either potential damage to hardware or loss of data and tells you how to avoid the problem. WARNING: A WARNING indicates a potential for property damage, personal injury, or death. © 2012 Dell Inc. Trademarks used in this text: Dell™, the DELL logo, Dell Precision™, Precision ON™,ExpressCharge™, Latitude™, Latitude ON™, OptiPlex™, Vostro™, and Wi-Fi Catcher™ are trademarks of Dell Inc. Intel®, Pentium®, Xeon®, Core™, Atom™, Centrino®, and Celeron® are registered trademarks or trademarks of Intel Corporation in the U.S. and other countries. AMD® is a registered trademark and AMD Opteron™, AMD Phenom™, AMD Sempron™, AMD Athlon™, ATI Radeon™, and ATI FirePro™ are trademarks of Advanced Micro Devices, Inc. Microsoft®, Windows®, MS-DOS®, Windows Vista®, the Windows Vista start button, and Office Outlook® are either trademarks or registered trademarks of Microsoft Corporation in the United States and/or other countries. Blu-ray Disc™ is a trademark owned by the Blu-ray Disc Association (BDA) and licensed for use on discs and players. The Bluetooth® word mark is a registered trademark and owned by the Bluetooth® SIG, Inc. and any use of such mark by Dell Inc. is under license. Wi-Fi® is a registered trademark of Wireless Ethernet Compatibility Alliance, Inc. 2012 - 10 Rev. A00 Contents Notes, Cautions, and Warnings...................................................................................................2 -

The Political and Military Aspects of Accession of Constantine the Great

Graeco-Latina Brunensia 24 / 2019 / 2 https://doi.org/10.5817/GLB2019-2-2 The Political and Military Aspects of Accession of Constantine the Great Stanislav Doležal (University of South Bohemia in České Budějovice) Abstract The article argues that Constantine the Great, until he was recognized by Galerius, the senior ČLÁNKY / ARTICLES Emperor of the Tetrarchy, was an usurper with no right to the imperial power, nothwithstand- ing his claim that his father, the Emperor Constantius I, conferred upon him the imperial title before he died. Tetrarchic principles, envisaged by Diocletian, were specifically put in place to supersede and override blood kinship. Constantine’s accession to power started as a military coup in which a military unit composed of barbarian soldiers seems to have played an impor- tant role. Keywords Constantine the Great; Roman emperor; usurpation; tetrarchy 19 Stanislav Doležal The Political and Military Aspects of Accession of Constantine the Great On 25 July 306 at York, the Roman Emperor Constantius I died peacefully in his bed. On the same day, a new Emperor was made – his eldest son Constantine who had been present at his father’s deathbed. What exactly happened on that day? Britain, a remote province (actually several provinces)1 on the edge of the Roman Empire, had a tendency to defect from the central government. It produced several usurpers in the past.2 Was Constantine one of them? What gave him the right to be an Emperor in the first place? It can be argued that the political system that was still valid in 306, today known as the Tetrarchy, made any such seizure of power illegal. -

270-271 Health Care Eligibility Benefit Inquiry And

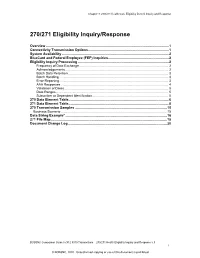

Chapter 3: 270/271 Health Care Eligibility Benefit Inquiry and Response 270/271 Eligibility Inquiry/Response Overview ...................................................................................................................................1 Connectivity Transmission Options ......................................................................................1 System Availability ..................................................................................................................2 BlueCard and Federal Employee (FEP) Inquiries ................................................................. 2 Eligibility Inquiry Processing ................................................................................................. 2 Frequency of Data Exchange ................................................................................................... 2 Acknowledgements .................................................................................................................. 2 Batch Data Retention ............................................................................................................... 3 Batch Handling ......................................................................................................................... 3 Error Reporting ......................................................................................................................... 3 AAA Responses ...................................................................................................................... -

The Cambridge Companion to Age of Constantine.Pdf

The Cambridge Companion to THE AGE OF CONSTANTINE S The Cambridge Companion to the Age of Constantine offers students a com- prehensive one-volume introduction to this pivotal emperor and his times. Richly illustrated and designed as a readable survey accessible to all audiences, it also achieves a level of scholarly sophistication and a freshness of interpretation that will be welcomed by the experts. The volume is divided into five sections that examine political history, reli- gion, social and economic history, art, and foreign relations during the reign of Constantine, a ruler who gains in importance because he steered the Roman Empire on a course parallel with his own personal develop- ment. Each chapter examines the intimate interplay between emperor and empire and between a powerful personality and his world. Collec- tively, the chapters show how both were mutually affected in ways that shaped the world of late antiquity and even affect our own world today. Noel Lenski is Associate Professor of Classics at the University of Colorado, Boulder. A specialist in the history of late antiquity, he is the author of numerous articles on military, political, cultural, and social history and the monograph Failure of Empire: Valens and the Roman State in the Fourth Century ad. Cambridge Collections Online © Cambridge University Press, 2007 Cambridge Collections Online © Cambridge University Press, 2007 The Cambridge Companion to THE AGE OF CONSTANTINE S Edited by Noel Lenski University of Colorado Cambridge Collections Online © Cambridge University Press, 2007 cambridge university press Cambridge, New York, Melbourne, Madrid, Cape Town, Singapore, Sao˜ Paulo Cambridge University Press 40 West 20th Street, New York, ny 10011-4211, usa www.cambridge.org Information on this title: www.cambridge.org/9780521818384 c Cambridge University Press 2006 This publication is in copyright. -

List of Approved Fire Alarm Companies

Approved Companies List Fire Alarm Company Wednesday, September 1, 2021 ____________________________________________________ App No. 198S Approval Exp: 2/22/2022 Company : AAA FIRE & SECURITY SYSTEMS Address: 67 WEST STREET UNIT 321 Brooklyn, NY 11222 Telephone #: 718-349-5950 Principal's Name: NAPHTALI LICHTENSTEIN “S” after the App No. means that Insurance Exp Date: 6/21/2022 the company is also an FDNY approved smoke detector ____________________________________________________ maintenance company. App No. 268S Approval Exp: 4/16/2022 Company : ABLE FIRE PREVENTION CORP. Address: 241 WEST 26TH STREET New York, NY 10001 Telephone #: 212-675-7777 Principal's Name: BRIAN EDWARDS Insurance Exp Date: 9/22/2021 ____________________________________________________ App No. 218S Approval Exp: 3/3/2022 Company : ABWAY SECURITY SYSTEM Address: 301 MCLEAN AVENUE Yonkers, NY 10705 Telephone #: 914-968-3880 Principal's Name: MARK STERNEFELD Insurance Exp Date: 2/3/2022 ____________________________________________________ App No. 267S Approval Exp: 4/14/2022 Company : ACE ELECTRICAL CONSTRUCTION Address: 130-17 23RD AVENUE College Point, NY 11356 Telephone #: 347-368-4038 Principal's Name: JEFFREY SOCOL Insurance Exp Date: 12/14/2021 30 days within today’s date Page 1 of 34 ____________________________________________________ App No. 243S Approval Exp: 3/23/2022 Company : ACTIVATED SYSTEMS INC Address: 1040 HEMPSTEAD TPKE, STE LL2 Franklin Square, NY 11010 Telephone #: 516-538-5419 Principal's Name: EDWARD BLUMENSTETTER III Insurance Exp Date: 5/12/2022 ____________________________________________________ App No. 275S Approval Exp: 4/27/2022 Company : ADR ELECTRONICS LLC Address: 172 WEST 77TH STREET #2D New York, NY 10024 Telephone #: 212-960-8360 Principal's Name: ALAN RUDNICK Insurance Exp Date: 1/31/2022 ____________________________________________________ App No. -

9. the CONSTITUTION the Structure of the League of the Aitolians, Born

9. THE CONSTITUTION The structure of the League of the Aitolians, born amid the turmoil of the Macedonian conquest of Greece and which survived with some difficulty the disintegration of that empire, is never described by any ancient source. It is thus not easy to discover, though a reason able estimate of it can be made. It is possible to collect together all the references to the various institutions of the league, and thus make a reasonably tidy picture of a functioning polity'. But this is an unsat isfactory method of procedure, resorted to all too often in studies of the ancient world. It means using evidence from, say, 313 alongside evidence from the 240s and the 180s, assuming they can all be lumped together, and so paying little regard to the very great changes which took place over that period. In 313 the league was a defensive, new state; in the 240s it was one of Greece's secondary powers, only just less important than the Macedonian kingdom; in the 180s it was a defeated state, heading for civil war. The friction of events and the mere passage of time clearly had their effects on the league's institu tions. The changes in Aitolia's international position over the period, for example, undoubtedly had their effects on the league's constitu tion. We do know of one change, which will make the point. The league council originally had only one secretary (grammateus), and later, from a little before 200, it had two, one of them senior to the other2• This was no doubt due to the greater workload in later years, though allowance must also be made for the inherent tendency of a bureau cracy to expand. -

High Performance Waxadditives

High Performance Wax Additives Advanced technology with a quality difference MICRO POWDERS, INC. 580 White Plains Road, Tarrytown, New York 10591 • Tel: (914) 793-4058, Fax: (914) 472-7098 • Email: [email protected] Quality, Innovation and Partnership Support Since 1971 About MPI For reliable quality and superb consistency in wax additives, formulators rely on Micro Powders®, the recognized leader in advanced wax technology. Our specialty products meet the demanding requirements of diverse markets, from paints, coatings and printing inks to ceramics, lubricants, adhesives and more. Our extensive range of micronized waxes, wax dispersions and wax emulsions brings the right solution to a vast array of applications, with reliable batch-to-batch consistency and superior performance values. Ongoing innovation keeps Micro Powders ahead of the curve in responding to industry trends. R&D takes place in our Advanced Applications Lab, staffed by chemists with many years experience in the industries we serve. The Micro Powders quality assurance system is certified to ISO 9001. Along with our technical expertise comes dedicated partnership support from our knowledgeable distributors worldwide and our own staff experts. Our advanced technology will make a quality difference in your products, and your profits. Unique Products Laser Diffraction Analysis ensures consistent particle size uniformity from batch-to-batch. Our wax additives are easily dispersed without prior melting or grinding. Product groups include: MP Synthetic Waxes for lubricity -

Anglo-Saxons

Anglo-Saxons Plated disc brooch Kent, England Late 6th or early 7th century AD Visit resource for teachers Key Stage 2 Anglo-Saxons Contents Before your visit Background information Resources Gallery information Preliminary activities During your visit Gallery activities: introduction for teachers Gallery activities: briefings for adult helpers Gallery activity: The Franks Casket Gallery activity: Personal adornment Gallery activity: Design and decoration Gallery activity: Anglo-Saxon jobs Gallery activity: Material matters After your visit Follow-up activities Anglo-Saxons Before your visit Anglo-Saxons Before your visit Background information The end of Roman Britain The Roman legions began to be withdrawn from Britain to protect other areas of the empire from invasion by peoples living on the edge of the empire at the end of the fourth century AD. Around AD 407 Constantine III, a claimant for the imperial throne based in Britain, led the troops from Britain to Gaul in an attempt to secure control of the Western Roman Empire. He failed and was killed in Gaul in AD 411. This left the Saxon Shore forts, which had been built by the Romans to protect the coast from attacks by raiding Saxons, virtually empty and the coast of Britain open to attack. In AD 410 there was a devastating raid on the undefended coasts of Britain and Gaul by Saxons raiders. Imperial governance in Britain collapsed and although aspects of Roman Britain continued after AD 410, Britain was no longer part of the Roman empire and saw increased settlement by Germanic people, particularly in the northern and eastern regions of England. -

Revisit Roman Arbeia a Story of Three Emperors: Teacher’S Notes

Revisit Roman Arbeia A Story of Three Emperors: teacher’s notes Revisit Roman Arbeia is split into four parts, all of which can be downloaded from Tyne & Wear Archives & Museums’ website: Tick: Gallery Search Fort site information Reconstruction Search A Story of Three Emperors How to use ‘A Story of Three Emperors’… ‘A Story of Three Emperors’ tells the true tale of Septimius Severus and his two sons, Geta and Caracalla. Images of artefacts linked to the story can be found within this document. This resource can be used either at Arbeia or in the classroom; you are welcome to use the story however you wish. A list of suggested classroom activities can be found below. Learning objectives • What was a Roman emperor? • Learning a new story Cautionary note This story involves death and murder. Suggested classroom activities • Write a newspaper story about Septimius Severus arriving at Arbeia, of the emperor dying in York, or the murder of either Geta or Caracalla. Alternatively, role play a news report. • Create a Roman Empire map and display it in your classroom. • Create a play of the story. • Illustrate the story. • Write a diary from Julia’s point of view. • Borrow a box of replica and authentic Roman objects from Tyne & Wear Archives & Museums. The Boxes of Delight are free of charge. More information can be found at www.exploreyourmuseums.org.uk . 1 A Story of Three Emperors A long time ago, the Roman Empire stretched from the hot, scorched deserts of northern Africa, over the deep blue Mediterranean Sea, covering the aromatic vineyards of France and ended in the cold, wet land of Britannia.