Arch of Constantine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Byzantine Missionaries, Foreign Rulers, and Christian Narratives (Ca

Conversion and Empire: Byzantine Missionaries, Foreign Rulers, and Christian Narratives (ca. 300-900) by Alexander Borislavov Angelov A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (History) in The University of Michigan 2011 Doctoral Committee: Professor John V.A. Fine, Jr., Chair Professor Emeritus H. Don Cameron Professor Paul Christopher Johnson Professor Raymond H. Van Dam Associate Professor Diane Owen Hughes © Alexander Borislavov Angelov 2011 To my mother Irina with all my love and gratitude ii Acknowledgements To put in words deepest feelings of gratitude to so many people and for so many things is to reflect on various encounters and influences. In a sense, it is to sketch out a singular narrative but of many personal “conversions.” So now, being here, I am looking back, and it all seems so clear and obvious. But, it is the historian in me that realizes best the numerous situations, emotions, and dilemmas that brought me where I am. I feel so profoundly thankful for a journey that even I, obsessed with planning, could not have fully anticipated. In a final analysis, as my dissertation grew so did I, but neither could have become better without the presence of the people or the institutions that I feel so fortunate to be able to acknowledge here. At the University of Michigan, I first thank my mentor John Fine for his tremendous academic support over the years, for his friendship always present when most needed, and for best illustrating to me how true knowledge does in fact produce better humanity. -

Waters of Rome Journal

TIBER RIVER BRIDGES AND THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE ANCIENT CITY OF ROME Rabun Taylor [email protected] Introduction arly Rome is usually interpreted as a little ring of hilltop urban area, but also the everyday and long-term movements of E strongholds surrounding the valley that is today the Forum. populations. Much of the subsequent commentary is founded But Rome has also been, from the very beginnings, a riverside upon published research, both by myself and by others.2 community. No one doubts that the Tiber River introduced a Functionally, the bridges in Rome over the Tiber were commercial and strategic dimension to life in Rome: towns on of four types. A very few — perhaps only one permanent bridge navigable rivers, especially if they are near the river’s mouth, — were private or quasi-private, and served the purposes of enjoy obvious advantages. But access to and control of river their owners as well as the public. ThePons Agrippae, discussed traffic is only one aspect of riparian power and responsibility. below, may fall into this category; we are even told of a case in This was not just a river town; it presided over the junction of the late Republic in which a special bridge was built across the a river and a highway. Adding to its importance is the fact that Tiber in order to provide access to the Transtiberine tomb of the river was a political and military boundary between Etruria the deceased during the funeral.3 The second type (Pons Fabri- and Latium, two cultural domains, which in early times were cius, Pons Cestius, Pons Neronianus, Pons Aelius, Pons Aure- often at war. -

ABSTRACT the Apostolic Tradition in the Ecclesiastical Histories Of

ABSTRACT The Apostolic Tradition in the Ecclesiastical Histories of Socrates, Sozomen, and Theodoret Scott A. Rushing, Ph.D. Mentor: Daniel H. Williams, Ph.D. This dissertation analyzes the transposition of the apostolic tradition in the fifth-century ecclesiastical histories of Socrates, Sozomen, and Theodoret. In the early patristic era, the apostolic tradition was defined as the transmission of the apostles’ teachings through the forms of Scripture, the rule of faith, and episcopal succession. Early Christians, e.g., Irenaeus, Tertullian, and Origen, believed that these channels preserved the original apostolic doctrines, and that the Church had faithfully handed them to successive generations. The Greek historians located the quintessence of the apostolic tradition through these traditional channels. However, the content of the tradition became transposed as a result of three historical movements during the fourth century: (1) Constantine inaugurated an era of Christian emperors, (2) the Council of Nicaea promulgated a creed in 325 A.D., and (3) monasticism emerged as a counter-cultural movement. Due to the confluence of these sweeping historical developments, the historians assumed the Nicene creed, the monastics, and Christian emperors into their taxonomy of the apostolic tradition. For reasons that crystallize long after Nicaea, the historians concluded that pro-Nicene theology epitomized the apostolic message. They accepted the introduction of new vocabulary, e.g. homoousios, as the standard of orthodoxy. In addition, the historians commended the pro- Nicene monastics and emperors as orthodox exemplars responsible for defending the apostolic tradition against the attacks of heretical enemies. The second chapter of this dissertation surveys the development of the apostolic tradition. -

Ba-English.Pdf

CLARION UNIVERSITY DEGREE: B.A. English College of Arts & Sciences REVISED CHECKSHEET with NEW INQ PLACEMENT Name Transfer: * Clarion ID ** Entrance Date CUP: _____ _____ _____ _____ _____ _____ _____ _____ Program Entry Date _____ _____ _____ _____ _____ _____ _____ _____ Advisor _____ _____ _____ _____ _____ _____ _____ _____ *************************************************************************************************************************************** GENERAL EDUCATION REQUIREMENTS - 48 CREDITS V. REQUIREMENT for the B.A. DEGREE (see note #1 on back of sheet) Foreign Language competency or coursework1: CR. GR. I. LIBERAL EDUCATION SKILLS - 12 CREDITS CR. GR. : A. English Composition (3 credits) : ENGL 111: College Writing II ____ ____ : : B. Mathematics Requirement (3 credits) : VI. REQUIREMENTS IN MAJOR (42 CREDITS) 1. CORE REQUIREMENTS (15 credits) C. Credits to total 12 in Category I, selected from at least two of the following: Academic Enrichment, MMAJ 140 or 340, ENGL 199: Introduction to English Studies ____ ____ Computer Information Science, CSD 465, Elementary Foreign ENGL 202: Reading & Writing: _______________ ____ ____ Language, English Composition, HON 128, INQ 100, Logic, ENGL 282: Intro to the English Language ____ ____ & Mathematics ENGL 303: Focus Studies: ___________________ ____ ____ ENGL 404: Advanced English Studies ____ ____ 2. BREADTH OF KNOWLEDGE2 (12 credits) : II. LIBERAL KNOWLEDGE - 27 CREDITS Two 200-level writing courses A. Physical & Biological Science (9 credits) selected from at least two of the following: Biology, Chemistry, Earth Sci., ENVR275, ENGL ____: ______________________________ ____ ____ GS411, HON230, Mathematics, Phys. Sci., & Physics. ENGL ____: ______________________________ ____ ____ : : Two 200-level literature courses : ENGL ____: ______________________________ ____ ____ B. Social & Behavioral Science (9 credits) selected from at least two ENGL ____: ______________________________ ____ ____ of the following: Anthropology, CSD125, CSD 257, Economics, Geography, GS 140, History, HON240, NURS320, Pol. -

French (08/31/21)

Bulletin 2021-22 French (08/31/21) evolved over time by interpreting related forms of cultural French representation and expression in order to develop an informed critical perspective on a matter of current debate. Contact: Tili Boon Cuillé Prerequisite: In-Perspective course. Phone: 314-935-5175 • In-Depth Courses (L34 French 370s-390s) Email: [email protected] These courses build upon the strong foundation students Website: http://rll.wustl.edu have acquired in In-Perspective courses. Students have the opportunity to take the plunge and explore a topic in the Courses professor’s area of expertise, learning to situate the subject Visit online course listings to view semester offerings for in its historical and cultural context and to moderate their L34 French (https://courses.wustl.edu/CourseInfo.aspx? own views with respect to those of other cultural critics. sch=L&dept=L34&crslvl=1:4). Prerequisite: In-Perspective course. Undergraduate French courses include the following categories: L34 French 1011 Essential French I Workshop Application of the curriculum presented in French 101D. Pass/ • Cultural Expression (French 307D) Fail only. Grade dependent on attendance and participation. Limited to 12 students. Students must be enrolled concurrently in This course enables students to reinforce and refine French 101D. their French written and oral expression while exploring Credit 1 unit. EN: H culturally rich contexts and addressing socially relevant questions. Emphasis is placed on concrete and creative L34 French 101D French Level I: Essential French I description and narration. Prerequisite: L34 French 204 or This course immerses students in the French language and equivalent. Francophone culture from around the world, focusing on rapid acquisition of spoken and written French as well as listening Current topic: Les Banlieues. -

Dell Vostro 270S Owner's Manual

Dell Vostro 270s Owner’s Manual Regulatory Model: D06S Regulatory Type: D06S001 Notes, Cautions, and Warnings NOTE: A NOTE indicates important information that helps you make better use of your computer. CAUTION: A CAUTION indicates either potential damage to hardware or loss of data and tells you how to avoid the problem. WARNING: A WARNING indicates a potential for property damage, personal injury, or death. © 2012 Dell Inc. Trademarks used in this text: Dell™, the DELL logo, Dell Precision™, Precision ON™,ExpressCharge™, Latitude™, Latitude ON™, OptiPlex™, Vostro™, and Wi-Fi Catcher™ are trademarks of Dell Inc. Intel®, Pentium®, Xeon®, Core™, Atom™, Centrino®, and Celeron® are registered trademarks or trademarks of Intel Corporation in the U.S. and other countries. AMD® is a registered trademark and AMD Opteron™, AMD Phenom™, AMD Sempron™, AMD Athlon™, ATI Radeon™, and ATI FirePro™ are trademarks of Advanced Micro Devices, Inc. Microsoft®, Windows®, MS-DOS®, Windows Vista®, the Windows Vista start button, and Office Outlook® are either trademarks or registered trademarks of Microsoft Corporation in the United States and/or other countries. Blu-ray Disc™ is a trademark owned by the Blu-ray Disc Association (BDA) and licensed for use on discs and players. The Bluetooth® word mark is a registered trademark and owned by the Bluetooth® SIG, Inc. and any use of such mark by Dell Inc. is under license. Wi-Fi® is a registered trademark of Wireless Ethernet Compatibility Alliance, Inc. 2012 - 10 Rev. A00 Contents Notes, Cautions, and Warnings...................................................................................................2 -

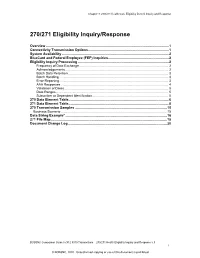

270-271 Health Care Eligibility Benefit Inquiry And

Chapter 3: 270/271 Health Care Eligibility Benefit Inquiry and Response 270/271 Eligibility Inquiry/Response Overview ...................................................................................................................................1 Connectivity Transmission Options ......................................................................................1 System Availability ..................................................................................................................2 BlueCard and Federal Employee (FEP) Inquiries ................................................................. 2 Eligibility Inquiry Processing ................................................................................................. 2 Frequency of Data Exchange ................................................................................................... 2 Acknowledgements .................................................................................................................. 2 Batch Data Retention ............................................................................................................... 3 Batch Handling ......................................................................................................................... 3 Error Reporting ......................................................................................................................... 3 AAA Responses ...................................................................................................................... -

The Cambridge Companion to Age of Constantine.Pdf

The Cambridge Companion to THE AGE OF CONSTANTINE S The Cambridge Companion to the Age of Constantine offers students a com- prehensive one-volume introduction to this pivotal emperor and his times. Richly illustrated and designed as a readable survey accessible to all audiences, it also achieves a level of scholarly sophistication and a freshness of interpretation that will be welcomed by the experts. The volume is divided into five sections that examine political history, reli- gion, social and economic history, art, and foreign relations during the reign of Constantine, a ruler who gains in importance because he steered the Roman Empire on a course parallel with his own personal develop- ment. Each chapter examines the intimate interplay between emperor and empire and between a powerful personality and his world. Collec- tively, the chapters show how both were mutually affected in ways that shaped the world of late antiquity and even affect our own world today. Noel Lenski is Associate Professor of Classics at the University of Colorado, Boulder. A specialist in the history of late antiquity, he is the author of numerous articles on military, political, cultural, and social history and the monograph Failure of Empire: Valens and the Roman State in the Fourth Century ad. Cambridge Collections Online © Cambridge University Press, 2007 Cambridge Collections Online © Cambridge University Press, 2007 The Cambridge Companion to THE AGE OF CONSTANTINE S Edited by Noel Lenski University of Colorado Cambridge Collections Online © Cambridge University Press, 2007 cambridge university press Cambridge, New York, Melbourne, Madrid, Cape Town, Singapore, Sao˜ Paulo Cambridge University Press 40 West 20th Street, New York, ny 10011-4211, usa www.cambridge.org Information on this title: www.cambridge.org/9780521818384 c Cambridge University Press 2006 This publication is in copyright. -

The Importance of Athanasius and the Views of His Character

The Importance of Athanasius and the Views of His Character J. Steven Davis Submitted to Dr. Jerry Sutton School of Divinity Liberty University September 19, 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter I: Research Proposal Abstract .............................................................................................................................11 Background ......................................................................................................................11 Limitations ........................................................................................................................18 Method of Research .........................................................................................................19 Thesis Statement ..............................................................................................................21 Outline ...............................................................................................................................21 Bibliography .....................................................................................................................27 Chapter II: Background of Athanasius An Influential Figure .......................................................................................................33 Early Life ..........................................................................................................................33 Arian Conflict ...................................................................................................................36 -

List of Approved Fire Alarm Companies

Approved Companies List Fire Alarm Company Wednesday, September 1, 2021 ____________________________________________________ App No. 198S Approval Exp: 2/22/2022 Company : AAA FIRE & SECURITY SYSTEMS Address: 67 WEST STREET UNIT 321 Brooklyn, NY 11222 Telephone #: 718-349-5950 Principal's Name: NAPHTALI LICHTENSTEIN “S” after the App No. means that Insurance Exp Date: 6/21/2022 the company is also an FDNY approved smoke detector ____________________________________________________ maintenance company. App No. 268S Approval Exp: 4/16/2022 Company : ABLE FIRE PREVENTION CORP. Address: 241 WEST 26TH STREET New York, NY 10001 Telephone #: 212-675-7777 Principal's Name: BRIAN EDWARDS Insurance Exp Date: 9/22/2021 ____________________________________________________ App No. 218S Approval Exp: 3/3/2022 Company : ABWAY SECURITY SYSTEM Address: 301 MCLEAN AVENUE Yonkers, NY 10705 Telephone #: 914-968-3880 Principal's Name: MARK STERNEFELD Insurance Exp Date: 2/3/2022 ____________________________________________________ App No. 267S Approval Exp: 4/14/2022 Company : ACE ELECTRICAL CONSTRUCTION Address: 130-17 23RD AVENUE College Point, NY 11356 Telephone #: 347-368-4038 Principal's Name: JEFFREY SOCOL Insurance Exp Date: 12/14/2021 30 days within today’s date Page 1 of 34 ____________________________________________________ App No. 243S Approval Exp: 3/23/2022 Company : ACTIVATED SYSTEMS INC Address: 1040 HEMPSTEAD TPKE, STE LL2 Franklin Square, NY 11010 Telephone #: 516-538-5419 Principal's Name: EDWARD BLUMENSTETTER III Insurance Exp Date: 5/12/2022 ____________________________________________________ App No. 275S Approval Exp: 4/27/2022 Company : ADR ELECTRONICS LLC Address: 172 WEST 77TH STREET #2D New York, NY 10024 Telephone #: 212-960-8360 Principal's Name: ALAN RUDNICK Insurance Exp Date: 1/31/2022 ____________________________________________________ App No. -

9. the CONSTITUTION the Structure of the League of the Aitolians, Born

9. THE CONSTITUTION The structure of the League of the Aitolians, born amid the turmoil of the Macedonian conquest of Greece and which survived with some difficulty the disintegration of that empire, is never described by any ancient source. It is thus not easy to discover, though a reason able estimate of it can be made. It is possible to collect together all the references to the various institutions of the league, and thus make a reasonably tidy picture of a functioning polity'. But this is an unsat isfactory method of procedure, resorted to all too often in studies of the ancient world. It means using evidence from, say, 313 alongside evidence from the 240s and the 180s, assuming they can all be lumped together, and so paying little regard to the very great changes which took place over that period. In 313 the league was a defensive, new state; in the 240s it was one of Greece's secondary powers, only just less important than the Macedonian kingdom; in the 180s it was a defeated state, heading for civil war. The friction of events and the mere passage of time clearly had their effects on the league's institu tions. The changes in Aitolia's international position over the period, for example, undoubtedly had their effects on the league's constitu tion. We do know of one change, which will make the point. The league council originally had only one secretary (grammateus), and later, from a little before 200, it had two, one of them senior to the other2• This was no doubt due to the greater workload in later years, though allowance must also be made for the inherent tendency of a bureau cracy to expand. -

The Emergence of Archival Records at Rome in the Fourth Century BCE

Foundations of History: The Emergence of Archival Records at Rome in the Fourth Century BCE by Zachary B. Hallock A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Greek and Roman History) in the University of Michigan 2018 Doctoral Committee: Professor David Potter, Chair Associate Professor Benjamin Fortson Assistant Professor Brendan Haug Professor Nicola Terrenato Zachary B. Hallock [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0003-0337-0181 © 2018 by Zachary B. Hallock To my parents for their endless love and support ii Acknowledgements I would like to thank Rackham Graduate School and the Departments of Classics and History for providing me with the resources and support that made my time as a graduate student comfortable and enjoyable. I would also like to express my gratitude to the professors of these departments who made themselves and their expertise abundantly available. Their mentoring and guidance proved invaluable and have shaped my approach to solving the problems of the past. I am an immensely better thinker and teacher through their efforts. I would also like to express my appreciation to my committee, whose diligence and attention made this project possible. I will be forever in their debt for the time they committed to reading and discussing my work. I would particularly like to thank my chair, David Potter, who has acted as a mentor and guide throughout my time at Michigan and has had the greatest role in making me the scholar that I am today. Finally, I would like to thank my wife, Andrea, who has been and will always be my greatest interlocutor.