Official Journal of the British Milers' Club

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

England Athletics Under 23 & Under 20 Championships 22

ENGLAND ATHLETICS UNDER 23 & UNDER 20 CHAMPIONSHIPS 22 & 23 JUNE 2019 @ BEDFORD RESULTS 400m Hurdles U20 Women AGE GROUP BEST: Shona Richards, Windsor Slough Eton & Hounslow, 56.16, 2014 CBP: Vicki Jamison, Lagan Valley AC, 57.27, 1996 Posn Bib Athlete Club Perf Heat 1 1 1114 Marcey Winter Windsor Slough Eton & Hounslow AC 60.58 Q 2 819 Steph Driscoll Liverpool Harriers & AC 61.72 Q 3 1086 Grace VansAgnew Crawley AC 62.26 Q 4 796 Jasmine Clark Middlesbrough Athletic Club (Mandale) 62.47 q 5 853 Neve Grimes Charnwood AC 64.96 6 798 Ellie Cleveland Windsor Slough Eton & Hounslow AC 65.30 7 885 Kati Hulme Shrewsbury AC 65.84 Posn Bib Athlete Club Perf Heat 2 1 768 Orla Brennan Windsor Slough Eton & Hounslow AC 60.82 Q 2 897 Jasmine Jolly Birchfield Harriers 61.37 Q 3 909 Jessica Lambert Crawley AC 61.42 Q 4 1021 Louise Robinson Birchfield Harriers 63.28 q 5 732 Olivia Allbut Jersey Spartan AC 67.80 6 1102 Rebecca Watkins Windsor Slough Eton & Hounslow AC 68.03 DQ 946 Meg McHugh Trafford Athletic Club Rule 168.7a 400m Hurdles U23 Women AGE GROUP BEST: Sally Gunnell, Essex Ladies AC, 54.03, 1988 CBP: Perri Shakes-Drayton, Victoria Park & Tower Hamlets, 55.34, 2009 Posn Bib Athlete Club Perf Heat 1 1 1090 Chelsea Walker City of York AC 61.48 Q 2 806 Emily Craig Edinburgh AC 61.68 Q 3 954 Jasmine Mitchell Loughborough Students 63.25 Q 4 1005 Ellie Ravenscroft Kidderminster and Stourport 63.96 q 5 906 Hannah Knights Guildford & Godalming AC 64.65 q 6 827 Sophie Elliss Croydon Harriers 65.00 Posn Bib Athlete Club Perf Heat 2 1 1112 Lauren Williams -

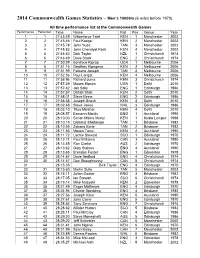

2014 Commonwealth Games Statistics – Men's

2014 Commonwealth Games Statistics – Men’s 10000m (6 miles before 1970) All time performance list at the Commonwealth Games Performance Performer Time Name Nat Pos Venue Year 1 1 27:45.39 Wilberforce Talel KEN 1 Manchester 2002 2 2 27:45.46 Paul Kosgei KEN 2 Manchester 2002 3 3 27:45.78 John Yuda TAN 3 Manchester 2002 4 4 27:45.83 John Cheruiyot Korir KEN 4 Manchester 2002 5 5 27:46.40 Dick Taylor NZL 1 Christchurch 1974 6 6 27:48.49 Dave Black ENG 2 Christchurch 1974 7 7 27:50.99 Boniface Kiprop UGA 1 Melbourne 2006 8 8 27:51.16 Geoffrey Kipngeno KEN 2 Melbourne 2006 9 9 27:51.99 Fabiano Joseph TAN 3 Melbourne 2006 10 10 27:52.36 Paul Langat KEN 4 Melbourne 2006 11 11 27:56.96 Richard Juma KEN 3 Christchurch 1974 12 12 27:57.39 Moses Kipsiro UGA 1 Delhi 2010 13 13 27:57.42 Jon Solly ENG 1 Edinburgh 1986 14 14 27:57.57 Daniel Salel KEN 2 Delhi 2010 15 15 27:58.01 Steve Binns ENG 2 Edinburgh 1986 16 16 27:58.58 Joseph Birech KEN 3 Delhi 2010 17 17 28:02.48 Steve Jones WAL 3 Edinburgh 1986 18 18 28:03.10 Titus Mbishei KEN 4 Delhi 2010 19 19 28:08.57 Eamonn Martin ENG 1 Auckland 1990 20 20 28:10.00 Simon Maina Munyi KEN 1 Kuala Lumpur 1998 21 21 28:10.15 Gidamis Shahanga TAN 1 Brisbane 1982 22 22 28:10.55 Zakaria Barie TAN 2 Brisbane 1982 23 23 28:11.56 Moses Tanui KEN 2 Auckland 1990 24 24 28:11.72 Lachie Stewart SCO 1 Edinburgh 1970 25 25 28:12.71 Paul Williams CAN 3 Auckland 1990 25 26 28:13.45 Ron Clarke AUS 2 Edinburgh 1970 27 27 28:13.62 Gary Staines ENG 4 Auckland 1990 28 28 28:13.65 Brendan Foster ENG 1 Edmonton 1978 29 29 28:14.67 -

Annual Report

ANNU2009AL REPORT S ONTENT C 2 From the President 5 Past Presidents 6 Office Bearers & Staff 8 Honour Roll Sub Committee Reports 10 Track & Field 13 Cross Country & Road Racing 17 Officials 21 Records 24 Statistics 25 Tracks Management Reports 26 From the Chief Executive 28 Programs 30 Development 36 Competition ANNUAL REPORT Competition Awards 40 XCR Awards 42 Summer Awards 44 Membership Statistics 46 Victorian Institute of Sport 48 Financial Report 2009 mission: to encourage, improve, promote and manage athletics in victoria. we will: .encourage participation in athletics by all people .provide for the development of athletes at all levels of ability from beginners to elite .increase the profile and awareness of athletics within the community .provide for the development of coaches, officials, administrators and other volunteers in athletics .provide financial ANNU2009AL REPORT viability From the President ANNE LORD, PRESIDENT, ATHLETICS VICTORIA Athletics Victoria continues to enjoy growth in Congratulations all aspects of our sport. Participation numbers continue to climb steadily. Financial growth has Not everyone can be publically applauded, but been important. AV needs to increase its surplus I would like to congratulate Pam Noden, John in order to maintain many of the programs Coleman and Martyn Kibel on their Official of previously supported by the government’s the Year awards. Moving Athletics Forward funding. Two of our members were recognized in the The continued growth of our sport over the Queen’s birthday honours. Congratulations past few years is due in part to a resurgence of to Paul Jenes and Ronda Jenkins who were athletics and running’s popularity amongst the both awarded the OAM for their contribution general public but also because of the great to athletics. -

2014 Commonwealth Games Statistics–Men's 5000M (3 Mi Before

2014 Commonwealth Games Statistics –Men’s 5000m (3 mi before 1970) by K Ken Nakamura All time performance list at the Commonwealth Games Performance Performer Time Name Nat Pos Venue Year 1 1 12:56.41 Augustine Choge KEN 1 Melbourne 2006 2 2 12:58.19 Craig Mottram AUS 2 Melbourne 2006 3 3 13:05.30 Benjamin Limo KEN 3 Melbourne 2006 4 4 13:05.89 Joseph Ebuya KEN 4 Melbourne 2006 5 5 13:12.76 Fabian Joseph TAN 5 Melbourne 2006 6 6 13:13.51 Sammy Kipketer KEN 1 Manchester 2002 7 13:13.57 Benjamin Limo 2 Manchester 2002 8 7 13:14.3 Ben Jipcho KEN 1 Christchurch 1974 9 8 13.14.6 Brendan Foster GBR 2 Christchurch 1974 10 9 13:18.02 Willy Kiptoo Kirui KEN 3 Manchester 2002 11 10 13:19.43 John Mayock ENG 4 Manchester 2002 12 11 13:19.45 Sam Haughian ENG 5 Manchester 2002 13 12 13:22.57 Daniel Komen KEN 1 Kuala Lumpur 1998 14 13 13:22.85 Ian Stewart SCO 1 Edinburgh 1970 15 14 13:23.00 Rob Denmark ENG 1 Victoria 1994 16 15 13:23.04 Henry Rono KEN 1 Edmonton 1978 17 16 13:23.20 Phillimon Hanneck ZIM 2 Victoria 1994 18 17 13:23.34 Ian McCafferty SCO 2 Edinburgh 1970 19 18 13:23.52 Dave Black ENG 3 Christchurch 1974 20 19 13:23.54 John Nuttall ENG 3 Victoria 1994 21 20 13:23.96 Jon Brown ENG 4 Victoria 1994 22 21 13:24.03 Damian Chopa TAN 6 Melbourne 2006 23 22 13:24.07 Philip Mosima KEN 5 Victoria 1994 24 23 13:24.11 Steve Ovett ENG 1 Edinburgh 1986 25 24 13:24.86 Andrew Lloyd AUS 1 Auckland 1990 26 25 13:24.94 John Ngugi KEN 2 Auckland 1990 27 26 13:25.06 Moses Kipsiro UGA 7 Melbourne 2006 28 13:25.21 Craig Mottram 6 Manchester 2002 29 27 13:25.63 -

Athletics Australia Almanac

HANDBOOK OF RECORDS & RESULTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Special thanks to the following for their support and contribution to Athletics Australia and the production of this publication. Rankings Paul Jenes (Athletics Australia Statistician) Records Ronda Jenkins (Athletics Australia Records Officer) Results Peter Hamilton (Athletics Australia Track & Field Commission) Paul Jenes, David Tarbotton Official photographers of Athletics Australia Getty Images Cover Image Scott Martin, VIC Athletics Australia Suite 22, Fawkner Towers 431 St Kilda Road Melbourne Victoria 3004 Australia Telephone 61 3 9820 3511 Facsimile 61 3 9820 3544 Email [email protected] athletics.com.au ABN 35 857 196 080 athletics.com.au Athletics Australia CONTENTS 2006 Handbook of Records & Results CONTENTS Page Page Messages – Athletics Australia 8 Australian Road & Cross Country Championships 56 – Australian Sports Commission 10 Mountain Running 57 50km and 100km 57 Athletics Australia Life Members & Merit Awards 11 Marathon and Half Marathon 58 Honorary Life Members 12 Road Walking 59 Recipients of the Merit Award of Athletics Australia 13 Cross Country 61 All Schools Cross Country 63 2006 Results Australian All Schools & Youth Athletics Championships 68 Telstra Selection Trials & 84th Australian Athletics Championships 15 Women 69 Women 16 Men 80 Men 20 Schools Knockout National Final 91 Australian Interstate Youth (Under 18) Match 25 Cup Competition 92 Women 26 Plate Competition 96 Men 27 Telstra A-Series Meets (including 2007 10,000m Championships at Zatopek) 102 -

Libro ING CAC1-36:Maquetación 1.Qxd

© Enrique Montesinos, 2013 © Sobre la presente edición: Organización Deportiva Centroamericana y del Caribe (Odecabe) Edición y diseño general: Enrique Montesinos Diseño de cubierta: Jorge Reyes Reyes Composición y diseño computadorizado: Gerardo Daumont y Yoel A. Tejeda Pérez Textos en inglés: Servicios Especializados de Traducción e Interpretación del Deporte (Setidep), INDER, Cuba Fotos: Reproducidas de las fuentes bibliográficas, Periódico Granma, Fernando Neris. Los elementos que componen este volumen pueden ser reproducidos de forma parcial siem- pre que se haga mención de su fuente de origen. Se agradece cualquier contribución encaminada a completar los datos aquí recogidos, o a la rectificación de alguno de ellos. Diríjala al correo [email protected] ÍNDICE / INDEX PRESENTACIÓN/ 1978: Medellín, Colombia / 77 FEATURING/ VII 1982: La Habana, Cuba / 83 1986: Santiago de los Caballeros, A MANERA DE PRÓLOGO / República Dominicana / 89 AS A PROLOGUE / IX 1990: Ciudad México, México / 95 1993: Ponce, Puerto Rico / 101 INTRODUCCIÓN / 1998: Maracaibo, Venezuela / 107 INTRODUCTION / XI 2002: San Salvador, El Salvador / 113 2006: Cartagena de Indias, I PARTE: ANTECEDENTES Colombia / 119 Y DESARROLLO / 2010: Mayagüez, Puerto Rico / 125 I PART: BACKGROUNG AND DEVELOPMENT / 1 II PARTE: LOS GANADORES DE MEDALLAS / Pasos iniciales / Initial steps / 1 II PART: THE MEDALS WINNERS 1926: La primera cita / / 131 1926: The first rendezvous / 5 1930: La Habana, Cuba / 11 Por deportes y pruebas / 132 1935: San Salvador, Atletismo / Athletics -

LIBRARY All Rights Reserved

LIBRARY All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if materia! had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Published by ProQuest LLC (2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 fA NEW DAWN RISING':1 AN EMPIRICAL AND SOCIAL STUDY CONCERNING THE EMERGENCE AND DEVELOPMENT OF ENGLISH WOMEN'S ATHLETICS UNTIL 1980 Gregory Paul Moon Submitted in part fulfilment for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at Roehampton Institute London for the University of Surrey August 1997 1Sutton and Cheam Advertiser 1979. Dawn Lucy (later Gaskin) was the first athlete I ever coached. Previously, she had made little progress for several years. In our first season together her improvement was such that the local newspaper was prompted to address her performances with this headline. ABSTRACT This study explores the history of English women's athletics, from the earliest references up to 1980. There is detailed discussion of smock racing and pedestrianism during the eighteenth- and nineteenth-centuries, but attention is focused on the period from 1921, when international and then domestic governing bodies were formed and athletics .became established as a legitimate sporting activity for women. -

2016 Olympic Games Statistics – Men's 10000M

2016 Olympic Games Statistics – Men’s 10000m by K Ken Nakamura Record to look for in Rio de Janeiro: 1) Last time KEN won gold at 10000m is back in 1968. Can Kamworor, Tanui or Karoki change that? 2) Can Mo Farah become sixth runner to win back to back gold? Summary Page: All time Performance List at the Olympic Games Performance Performer Time Name Nat Pos Venue Year 1 1 27:01.17 Kenenisa Bekele ETH 1 Beijing 2008 2 2 27:02.77 Sileshi Sihine ETH 2 Beijing 2008 3 3 27:04.11 Micah Kogo KEN 3 Beijing 2008 4 4 27:04.11 Moses Masai KEN 4 Beijing 2008 5 27:05.10 Kenenisa Bekele 1 Athinai 2004 6 5 27:05.11 Zersenay Tadese ERI 5 Beijing 2008 7 6 27:06.68 Haile Gebrselassie ETH 6 Beijing 2008 8 27:07.34 Haile Gebrselassie 1 Atlanta 1996 Slowest winning time since 1972: 27:47.54 by Alberto Cova (ITA) in 1984 Margin of Victory Difference Winning time Name Nat Venue Year Max 47.8 29:59.6 Emil Zatopek TCH London 1948 18.68 27:47.54 Alberto Cova ITA Los Angeles 1984 Min 0.09 27:18.20 Haile Gebrselassie ETH Sydney 2000 Second line is largest margin since 1952 Best Marks for Places in the Olympics Pos Time Name Nat Venue Year 1 27:01.17 Kenenisa Bekele ETH Beijing 2008 2 27:02.77 Sileshi Sihine ETH Beijing 2008 3 27:04.11 Micah Kogo KEN Beijing 2008 4 27:04.11 Moses Masai KEN Beijing 2008 5 27:05.11 Zersenay Tadese ERI Beijing 2008 6 27:06.68 Haile Gebrselassie ETH Beijing 2008 7 27:08.25 Martin Mathathi KEN Beijing 2008 Multiple Gold Medalists: Kenenisa Bekele (ETH): 2004, 2008 Haile Gebrselassie (ETH): 1996, 2000 Lasse Viren (FIN): 1972, 1976 Emil -

Birmingham Commonwealth Games 2022: Cultural Programme

Birmingham Commonwealth Games 2022: Cultural Programme Chair Alan Heap Purple Monster Christina Boxer Warwick District Council Tim Hodgson & Louisa Davies Senior Producers (Cultural Programme & Live Sites) for Birmingham 2022. Christina Boxer Warwick District Council BOWLS & PARA BOWLS Warwick District VENUE 2022 Commonwealth Games Project ENHANCED Introduction ENVIRONMENT, PHYSICAL ACTIVITY & WELLBEING Spark Symposium 14.02.2020 MAXIMISING OPPORTUNITIES TO SHOWCASE LOCAL ENTERPRISE, CULTURE, TOURISM www.warwickdc.gov.uk & EVENTS Venues – A Regional Showcase Birmingham2022www.warwickdc.gov.uk presentation | slide26/01/2018 Lawn Bowls & Para Bowls o Matches on 9 days of competition o Minimum 2 sessions a day o 5,000 – 6,000 visitors to the District daily - Spectators - Competitors - Officials - Volunteers - Media o 240 lawn bowls competitors (2018) o Integrated Para Bowls o 28 nations (2018) www.warwickdc.gov.uk | 26/01/2018Jan 2020 WDC Commonwealth Games Project Objectives Successful CG2022 Bowls & Para Bowls Improved Bowls Venue Competition Participation & Diversity Enhanced Wider Victoria Park Facilities, Access & Riverside Links Raised Awareness of the Wellbeing Benefits of an Active Lifestyle Maximised Opportunities for Local Enterprise, Culture, Tourism and Showcasing WDC’s Reputation for Events Delivery www.warwickdc.gov.ukApril | 26/01/2018 2017 – March 2023 Louisa Davies Tim Hodgson Senior Producers, Cultural Programme & Live Sites - BIRMINGHAM 2022 BIRMINGHAM 2022 CULTURAL PROGRAMME Introduction Spark 14 February 2020 INTRODUCTION -

2018 Continental Cup Statistics – Men's 1500M

2018 Continental Cup Statistics – Men’s 1500m - by K Ken Nakamura All time performance list at the World/Continental Cup Performance Performer Time Name Team Pos Venue Year 1 1 3:31.20 Bernard Lagat AFR 1 Madrid 2002 2 2 3:33.67 Reyes Estevez ESP 2 Madrid 2002 3 3 3:34.45 Steve Ovett EUR 1 Düsseldorf 1977 4 4 3:34.70 Noureddine Morceli AFR 1 London 1994 5 3:34.95 Steve Ovett 1 Roma 1981 6 5 3:35.49 John Walker OCE 2 Roma 1981 6 5 3:35.49 Amine Laalou AFR 1 Split 2010 8 7 3:35.56 Abdi Bile AFR 1 Barcelona 1989 9 8 3:35.58 Olaf Beyer GDR 3 Roma 1981 10 9 3:35.70 Mekonnen Gebremedhin AFR 2 Split 2010 11 10 3:35.79 Sebastian Coe GBR 2 Barcelona 1989 12 11 3:35.87 Jens-Peter Herold GDR 3 Barcelona 1989 13 12 3:35.98 Thomas Wessinghage FRG 2 Düsseldorf 1977 14 13 3:36.29 Mike Boit AFR 4 Roma 1981 15 14 3:36.48 Leonel Manzano AME 3 Split 2010 16 15 3:36.56 Sydney Maree USA 5 Roma 1981 17 16 3:36.65 Gennaro Di Napoli EUR 4 Barcelona 1989 18 17 3:37.43 Arturo Casado EUR 4 Split 2010 19 18 3.37.5 Jürgen Straub GDR 3 Düsseldorf 1977 20 19 3:37.8 Abderrahmane Morceli AFR 4 Düsseldorf 1977 21 20 3:38.04 Mehdi Baala EUR 3 Madrid 2002 Slowest winning time: 3:52.60 by Alex Kipchirchir Rono (AFR) in 2006 Margin of Victory Difference Winning Time Name Team Venue Year Max 5.34 3:34.70 Noureddine Morceli AFR London 1994 Min 0.08 3:40.87 Laban Rotich AFR Johannesburg 1998 Best Marks for Places in the World/Continental Cup Pos Time Name Team Venue Year 1 3:31.20 Bernard Lagat AFR Madrid 2002 2 3:33.67 Reyes Estevez ESP Madrid 2002 3 3:35.58 Olaf Beyer GDR Roma -

USATF Cross Country Championships Media Handbook

TABLE OF CONTENTS NATIONAL CHAMPIONS LIST..................................................................................................................... 2 NCAA DIVISION I CHAMPIONS LIST .......................................................................................................... 7 U.S. INTERNATIONAL CROSS COUNTRY TRIALS ........................................................................................ 9 HISTORY OF INTERNATIONAL CHAMPIONSHIPS ........................................................................................ 20 APPENDIX A – 2009 USATF CROSS COUNTRY CHAMPIONSHIPS RESULTS ............................................... 62 APPENDIX B –2009 USATF CLUB NATIONAL CHAMPIONSHIPS RESULTS .................................................. 70 USATF MISSION STATEMENT The mission of USATF is to foster sustained competitive excellence, interest, and participation in the sports of track & field, long distance running, and race walking CREDITS The 30th annual U.S. Cross Country Handbook is an official publication of USA Track & Field. ©2011 USA Track & Field, 132 E. Washington St., Suite 800, Indianapolis, IN 46204 317-261-0500; www.usatf.org 2011 U.S. Cross Country Handbook • 1 HISTORY OF THE NATIONAL CHAMPIONSHIPS USA Track & Field MEN: Year Champion Team Champion-score 1954 Gordon McKenzie New York AC-45 1890 William Day Prospect Harriers-41 1955 Horace Ashenfelter New York AC-28 1891 M. Kennedy Prospect Harriers-21 1956 Horace Ashenfelter New York AC-46 1892 Edward Carter Suburban Harriers-41 1957 John Macy New York AC-45 1893-96 Not Contested 1958 John Macy New York AC-28 1897 George Orton Knickerbocker AC-31 1959 Al Lawrence Houston TFC-30 1898 George Orton Knickerbocker AC-42 1960 Al Lawrence Houston TFC-33 1899-1900 Not Contested 1961 Bruce Kidd Houston TFC-35 1901 Jerry Pierce Pastime AC-20 1962 Pete McArdle Los Angeles TC-40 1902 Not Contested 1963 Bruce Kidd Los Angeles TC-47 1903 John Joyce New York AC-21 1964 Dave Ellis Los Angeles TC-29 1904 Not Contested 1965 Ron Larrieu Toronto Olympic Club-40 1905 W.J. -

Los Dobles Especialistas En Distancias Consecutivas José María García

Los dobles especialistas en distancias consecutivas José María García 1 - INTRODUCCION 2 - TABLAS DE EQUIVALENCIAS PARA DOBLES ESPECIALISTAS 3 - LA REVOLUCION SINTETICA 4 - CRONOLOGIA MUNDIAL Y EUROPEA (desde el siglo XIX hasta 31.12.2004) 5 - RANKINGS MUNDIALES (200 atletas) 1 - INTRODUCCION A mediados de los años cincuenta (cuando era- mos jóvenes atletas) uno de los temas más inte- resantes para aquellos de nosotros que seguíamos el atletismo internacional, era conocer y valorar las marcas personales de los milleros y fondistas en todas las distancias (de 800 a 10000) y tratar de evaluar a partir de cada récord en una prueba qué marca podría conseguirse en las distancias pró- ximas. Las tablas de puntuación -finlandesa y sueca- ayudaban algo aunque sus carencias en mediofondo y fondo eran notorias; me refiero tanto a la au- Michel Jazy: en 1962 era el mejor en el “pentathlon sencia de las distancias en millas (la finlandesa pedestre” seguido de Murray Halberg. no recogía ninguna y la sueca sólo puntuaba la milla y las 2 millas es decir olvidándose de las 3 que en 1962 se había alcanzado la cifra de 100 y 6 millas) como al desequilibrio que se apreciaba carreras por debajo de dicha barrera. A conti- en la valoración de determinadas distancias. nuación me pareció oportuno -como segundo Era la época -primavera de 1954- del asalto al artículo- actualizar las marcas de los mediofon- muro de los 4 minutos en la milla (3.59.4 Bannister distas y fondistas (de 800 a 10000). Se me ocu- y al mes siguiente Landy 3.58.0), de las galopa- rrió que un buen título sería “El pentathlon pe- das solitarias de Zatopek quitándole el récord de destre”, es decir escogiendo en cada caso las 5 5000 al sueco Hägg por un segundo (13.57.2) y mejores pruebas de cada atleta y puntuándolas por derribando otra barrera (los 29 minutos en 10000 la tabla en vigor en aquel momento o sea la sue- con 28.54.2).