LIBRARY All Rights Reserved

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

20 Top-Ten Shot

Last Updated – 21.10.2015 EUROPEAN ALL TIME RANKINGS MEN SHOT PUT M35 – 39 (Weight 7.250 kg) DISTANCE NAME NATION BORN MEET PLACE MEET DATE 22.10 Andrei Mikhnevich BLR 12.07.1976 Minsk 11.08.2011 21.35 Aleksander Baryshnikov RUS 11.11.1948 Sochi 10.06.1984 20.91 Dragan Perić SRB 08.05.1964 Edmonton 04.08.2001 20.90 Saulius Kleiza LTU 02.04.1964 Kaunas 14.05.1999 20.84 Matti Yrjölä FIN 26.03.1938 Kobemäki 06.07.1976 20.79 Milan Haborak SVK 11.01.1973 Pacov 11.07.2008 20.78 Roman Virastyuk UKR 20.04.1968 Kiev 03.07.2003 20.70 Wladyslaw Komar POL 11.04.1940 Chemnitz 26.06.1977 20.67 Hamza Alic BIH 20.01.1979 Bistrica 30.05.2015 20.54 Jovan Lazarevic SRB 03.05.1952 Minsk 26.07.1990 INDOOR 21.04 Gheorghe Guset ROU 18.05.1968 Bucarest 18.02.2006 20.85 Mark Proctor GBR 15.01.1963 Kings Lynn 18.01.1998 20.76 Valery Voykin RUS 14.10.1945 Leningrado 29.01.1983 * * * SHOT PUT M40 – 44 (Weight 7.250 kg) DISTANCE NAME NATION BORN MEET PLACE MEET DATE 20.44 Ivan Ivancic SRB 06.12.1937 Beograd 05.07.1980 20.34 Dragan Perić SRB 08.05.1964 Zenica 02.09.2006 20.04 Mark Proctor GBR 15.01.1963 Manchester 30.08.2005 19.97 Waldyslaw Komar POL 11.04.1940 Warsaw 06.09.1980 19.77 Pierre Colnard FRA 18.02.1929 Colombes 18.07.1970 19.18 Matti Yrjölä FIN 26.03.1938 Somero 16.07.1978 19.10 Paolo Dal Soglio ITA 29.07.1970 Savona 10.06.2012 19.09 Ferdinand Schladen GER 24.05.1939 Höhr 06.09.1981 19.08 Paul Edwards GBR 16.02.1959 Luton 16.06.1999 19.07 Alessandro Andrei ITA 03.01.1959 Pescara 23.07.2000 INDOOR 19.48 Ivan Ivancic SRB 06.12.1937 Sindelfingen 02.03.1980 * * * SHOT PUT M45 – 49 (Weight 7.250 kg) DISTANCE NAME NATION BORN MEET PLACE MEET DATE 20.77 Ivan Ivancic SRB 06.12.1937 Coblenz 31.08.1983 18.22 Gudmund. -

Athletics Kenya Calendar of Events 2017-2018

ATHLETICS KENYA / IAAF CALENDAR OF EVENTS FOR THE YEAR 2017/2018 SEASON. NOVEMBER 2017 2nd Athletics Kenya Anti-Doping Sensitization Day All Counties KEN 4th 1st Athletics Kenya Cross Country Series Nairobi KEN 4th Baringo Half Marathon Kabarnet KEN 5th Marathon des Alpes-Maritimes Nice Cannes Nice FRA 5th TSC New York Marathon New York USA 11th 2nd Athletics Kenya Cross Country Series Sotik KEN 11th Tegla Loroupe 10Km Peace Run Kapenguria KEN 12th Saitama International Marathon Saitama JPN 12th BLOM BANK Beirut Marathon Beirut LBN 12th Shangai International Marathon Shanghai CHN 12th Vodafone Istanbul Marathon Istanbul TUR 12th Kass Marathon Eldoret KEN 17th - 18th 1st A.K Track & Field Competition Moi Stadium KEN Kisumu 19th Semi- Marathon de Boulogne Billancourt Christian Granger Boulogne FRA 19th Maraton Valencia Trinidad Alfonso Valencia ESP 19th Airtel Delhi Half Marathon Delhi IND 25th Tusky’s Mattress Wareng Cross Country Eldoret KEN 25th 3rd A.K Cross Country Series Nyandarua TTC KEN 26th Marathon du Gabon GAB 26th Firenze Marathon Firenze ITA DECEMBER 2017 1st World Aids Marathon Kisumu KEN 1st - 2nd 2nd A.K Track & Field Competition Kisii KEN 3rd 71st Fukuoka International Open Marathon Championships Fukuoka JPN 3rd Standard Chartered Marathon Singapore Singapore SIN 6th AK Gala Nairobi KEN 9th 4th A.K Cross Country Series Iten KEN 10th Imenti 15Km Road Race Meru KEN 10th Guangzhou Marathon Guangzhou CHN 15th - 16th 3rd A.K Track & Field Competition Machakos KEN 17th Safaricom Kisumu City National Marathon Kisumu KEN 17th Shenzhen -

I TEAM JAPAN: THEMES of 'JAPANESENESS' in MASS MEDIA

i TEAM JAPAN: THEMES OF ‘JAPANESENESS’ IN MASS MEDIA SPORTS NARRATIVES A Dissertation submitted to the Temple University Graduate Board In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Michael Plugh July 2015 Examining Committee Members: Fabienne Darling-Wolf, Advisory Chair, Media and Communication Doctoral Program Nancy Morris, Media and Communication Doctoral Program John Campbell, Media and Communication Doctoral Program Lance Strate, External Member, Fordham University ii © Copyright 2015 by MichaelPlugh All Rights Reserved iii Abstract This dissertation concerns the reproduction and negotiation of Japanese national identity at the intersection between sports, media, and globalization. The research includes the analysis of newspaper coverage of the most significant sporting events in recent Japanese history, including the 2014 Koshien National High School Baseball Championships, the awarding of the People’s Honor Award, the 2011 FIFA Women’s World Cup, wrestler Hakuho’s record breaking victories in the sumo ring, and the bidding process for the 2020 Olympic Games. 2054 Japanese language articles were examined by thematic analysis in order to identify the extent to which established themes of “Japaneseness” were reproduced or renegotiated in the coverage. The research contributes to a broader understanding of national identity negotiation by illustrating the manner in which established symbolic boundaries are reproduced in service of the nation, particularly via mass media. Furthermore, the manner in which change is negotiated through processes of assimilation and rejection was considered through the lens of hybridity theory. iv To my wife, Ari, and my children, Hiroto and Mia. Your love sustained me throughout this process. -

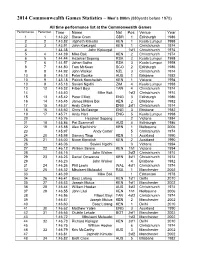

2014 Commonwealth Games Statistics – Men's 800M

2014 Commonwealth Games Statistics – Men’s 800m (880yards before 1970) All time performance list at the Commonwealth Games Performance Performer Time Name Nat Pos Venue Year 1 1 1:43.22 Steve Cram GBR 1 Edinburgh 1986 2 2 1:43.82 Japheth Kimutai KEN 1 Kuala Lumpur 1998 3 3 1:43.91 John Kipkurgat KEN 1 Christchurch 1974 4 1:44.38 John Kipkurgat 1sf1 Christchurch 1974 5 4 1:44.39 Mike Boit KEN 2 Christchurch 1974 6 5 1:44.44 Hezekiel Sepeng RSA 2 Kuala Lumpur 1998 7 6 1:44.57 Johan Botha RSA 3 Kuala Lumpur 1998 8 7 1:44.80 Tom McKean SCO 2 Edinburgh 1986 9 8 1:44.92 John Walker NZL 3 Christchurch 1974 10 9 1:45.18 Peter Bourke AUS 1 Brisbane 1982 10 9 1:45.18 Patrick Konchellah KEN 1 Victoria 1994 10 9 1:45.18 Savieri Ngidhi ZIM 4 Kuala Lumpur 1998 13 12 1:45.32 Filbert Bayi TAN 4 Christchurch 1974 14 1:45.40 Mike Boit 1sf2 Christchurch 1974 15 13 1:45.42 Peter Elliott ENG 3 Edinburgh 1986 16 14 1:45.45 James Maina Boi KEN 2 Brisbane 1982 17 15 1:45.57 Andy Carter ENG 2sf1 Christchurch 1974 18 16 1:45.60 Chris McGeorge ENG 3 Brisbane 1982 19 17 1:45.71 Andy Hart ENG 5 Kuala Lumpur 1998 20 1:45.76 Hezekiel Sepeng 2 Victoria 1994 21 18 1:45.86 Pat Scammell AUS 4 Edinburgh 1986 22 19 1:45.88 Alex Kipchirchir KEN 1 Melbourne 2006 23 1:45.97 Andy Carter 5 Christchurch 1974 24 20 1:45.98 Sammy Tirop KEN 1 Auckland 1990 25 21 1:46.00 Nixon Kiprotich KEN 2 Auckland 1990 26 1:46.06 Savieri Ngidhi 3 Victoria 1994 27 22 1:46.12 William Serem KEN 1h1 Victoria 1994 28 1:46.15 John Walker 2sf2 Christchurch 1974 29 23 1:46.23 Daniel Omwanza KEN 3sf1 Christchurch -

Official Journal of the British Milers' Club

Official Journal of the British Milers’ Club VOLUME 3 ISSUE 14 AUTUMN 2002 The British Milers’ Club Contents . Sponsored by NIKE Founded 1963 Chairmans Notes . 1 NATIONAL COMMITTEE President Lt. CoI. Glen Grant, Optimum Speed Distribution in 800m and Training Implications C/O Army AAA, Aldershot, Hants by Kevin Predergast . 1 Chairman Dr. Norman Poole, 23 Burnside, Hale Barns WA15 0SG An Altitude Adventure in Ethiopia by Matt Smith . 5 Vice Chairman Matthew Fraser Moat, Ripple Court, Ripple CT14 8HX End of “Pereodization” In The Training of High Performance Sport National Secretary Dennis Webster, 9 Bucks Avenue, by Yuri Verhoshansky . 7 Watford WD19 4AP Treasurer Pat Fitzgerald, 47 Station Road, A Coach’s Vision of Olympic Glory by Derek Parker . 10 Cowley UB8 3AB Membership Secretary Rod Lock, 23 Atherley Court, About the Specificity of Endurance Training by Ants Nurmekivi . 11 Upper Shirley SO15 7WG BMC Rankings 2002 . 23 BMC News Editor Les Crouch, Gentle Murmurs, Woodside, Wenvoe CF5 6EU BMC Website Dr. Tim Grose, 17 Old Claygate Lane, Claygate KT10 0ER 2001 REGIONAL SECRETARIES Coaching Frank Horwill, 4 Capstan House, Glengarnock Avenue, E14 3DF North West Mike Harris, 4 Bruntwood Avenue, Heald Green SK8 3RU North East (Under 20s)David Lowes, 2 Egglestone Close, Newton Hall DH1 5XR North East (Over 20s) Phil Hayes, 8 Lytham Close, Shotley Bridge DH8 5XZ Midlands Maurice Millington, 75 Manor Road, Burntwood WS7 8TR Eastern Counties Philip O’Dell, 6 Denton Close, Kempston MK Southern Ray Thompson, 54 Coulsdon Rise, Coulsdon CR3 2SB South West Mike Down, 10 Clifton Down Mansions, 12 Upper Belgrave Road, Bristol BS8 2XJ South West Chris Wooldridge, 37 Chynowen Parc, GRAND PRIX PRIZES (Devon and Cornwall) Cubert TR8 5RD A new prize structure is to be introduced for the 2002 Nike Grand Prix Series, which will increase Scotland Messrs Chris Robison and the amount that athletes can win in the 800m and 1500m races if they run particular target times. -

Todos Los Medallistas De Los Campeonatos De Europa

TODOS LOS MEDALLISTAS DE LOS CAMPEONATOS DE EUROPA HOMBRES 100 m ORO PLATA BRONCE Viento 1934 Christiaan Berger NED 10.6 Erich Borchmeyer GER 10.7 József Sir HUN 10.7 1938 Martinus Osendarp NED 10.5 Orazio Mariani ITA 10.6 Lennart Strandberg SWE 10.6 1946 Jack Archer GBR 10.6 Håkon Tranberg NOR 10.7 Carlo Monti ITA 10.8 1950 Étienne Bally FRA 10.7 Franco Leccese ITA 10.7 Vladimir Sukharev URS 10.7 0.7 1954 Heinz Fütterer FRG 10.5 René Bonino FRA 10.6 George Ellis GBR 10.7 1958 Armin Hary FRG 10.3 Manfred Germar FRG 10.4 Peter Radford GBR 10.4 1.5 1962 Claude Piquemal FRA 10.4 Jocelyn Delecour FRA 10.4 Peter Gamper FRG 10.4 -0.6 1966 Wieslaw Maniak POL 10.60 Roger Bambuck FRA 10.61 Claude Piquemal FRA 10.62 -0.6 1969 Valeriy Borzov URS 10.49 Alain Sarteur FRA 10.50 Philippe Clerc SUI 10.56 -2.7 1971 Valeriy Borzov URS 10.26 Gerhard Wucherer FRG 10.48 Vassilios Papageorgopoulos GRE 10.56 -1.3 1974 Valeriy Borzov URS 10.27 Pietro Mennea ITA 10.34 Klaus-Dieter Bieler FRG 10.35 -1.0 1978 Pietro Mennea ITA 10.27 Eugen Ray GDR 10.36 Vladimir Ignatenko URS 10.37 0.0 1982 Frank Emmelmann GDR 10. 21 Pierfrancesco Pavoni ITA 10. 25 Marian Woronin POL 10. 28 -080.8 1986 Linford Christie GBR 10.15 Steffen Bringmann GDR 10.20 Bruno Marie-Rose FRA 10.21 -0.1 1990 Linford Christie GBR 10.00w Daniel Sangouma FRA 10.04w John Regis GBR 10.07w 2.2 1994 Linford Christie GBR 10.14 Geir Moen NOR 10.20 Aleksandr Porkhomovskiy RUS 10.31 -0.5 1998 Darren Campbell GBR 10.04 Dwain Chambers GBR 10.10 Charalambos Papadias GRE 10.17 0.3 2002 Francis Obikwelu POR 10.06 -

Peso Olímpico. Datos Mujeres

LOS LANZAMIENTOS EN LOS JJOO PROGRESIÓN RECORD OLÍMPICO JUEGOS OLÍMPICOS. PODIUM LANZAMIENTO DE PESO. MUJERES LANZAMIENTO DE PESO MUJERES • 13.14 Micheline Ostermeyer FRA London Aug 04, 1948 SEDE ORO PLATA BRONCE • 13.75 Micheline Ostermeyer FRA London Aug 04, 1948 London 1948 Micheline Ostermeyer FRA 13,75 Amelia Piccinini ITA 13,09 Ine Schäffer AUT 13,08 • 13.88 Klavdiya Tochenova URS Helsinki Jul 26, 1952 Helsinki 1952 Galina Zybina URS 15,28 Marianne Werner FRG 14,57 Klavdiya Tochenova URS 14,50 • 13.89 Marianne Werner FRG Helsinki Jul 26, 1952 Melbourne 1956 Tamara Tishkevich URS 16,59 Galina Zybina URS 16,53 Marianne Werner FRG 15,61 • 15.00 Galina Zybina URS Helsinki Jul 26, 1952 Rome 1960 Tamara Press URS 17,32 Johanna Lüttge GDR 16,61 Earlene Brown USA 16,42 • 15.28 Galina Zybina URS Helsinki Jul 26, 1952 Tokyo 1964 Tamara Press URS 18,14 Renate Garisch GDR 17,61 Galina Zybina URS 17,45 • 16.35 Galina Zybina URS Melbourne Nov 30, 1956 Mexico 1968 Margitta Gummel GDR 19,61 Marita Lange GDR 18,78 Nadezhda Chizhova URS 18,19 • 16.48 Galina Zybina URS Melbourne Nov 30, 1956 Munich 1972 Nadezhda Chizhova URS 21,03 Margitta Gummel GDR 20,22 Ivanka Khristova BUL 19,35 • 16.53 Galina Zybina URS Melbourne Nov 30, 1956 Montreal 1976 Ivanka Khristova BUL 21,16 Nadezhda Chizhova URS 20,96 Helena Fibingerova TCH 20,67 • 16.59 Tamara Tishkevich URS Melbourne Nov 30, 1956 Moscow 1980 Ilona Slupianek GDR 22,41 Esfir Krachevskaya URS 21,42 Margitta Pufe GDR 21,20 • 17.32 Tamara Press URS Rome Sep 02, 1960 Los Angeles 1984 Claudia Losch FRG 20,48 -

0 Eulogy Delivered by Alan Jones Ao Honouring the Life

EULOGY DELIVERED BY ALAN JONES AO HONOURING THE LIFE OF BETTY CUTHBERT AM MBE AT THE SYDNEY CRICKET GROUND MONDAY 21 AUGUST 2017 0 There is a crushing reminder of our own mortality in being here today to honour and remember the unyieldingly great Betty Cuthbert, AM. MBE. Four Olympic gold medals, one Commonwealth Games gold medal, two silver medals, 16 world records. The 1964 Helms World Trophy for Outstanding Athlete of the Year in all amateur sports in Australia. And it’s entirely appropriate that this formal and official farewell, sponsored by the State Government of New South Wales, should be taking place in this sporting theatre, which Betty adorned and indeed astonished in equal measure. It was here that in preparation for the Cardiff Empire Games in 1958 and the Rome Olympics in 1960, as the Games were being held in the Northern Hemisphere, out of season for Australian athletes, that winter competition was arranged to bring them to their peak. Races were put on here at the Sydney Cricket Ground at half time during a rugby league game. And it was in July 1978, as Betty was suffering significantly, but not publicly, from multiple sclerosis, that the government of New South Wales invited Betty Cuthbert to become the first woman member of the Sydney Cricket Ground Trust. Of course, in the years since that appointment, as Betty herself acknowledged, her road became often rocky and steep. 1 She once talked about the pitfalls, the craters and the hurdles. But along the way, she found many revival points. -

Athletics at the 1974 British Commonwealth Games - Wikipedia

28/4/2020 Athletics at the 1974 British Commonwealth Games - Wikipedia Athletics at the 1974 British Commonwealth Games At the 1974 British Commonwealth Games, the athletics events were held at the Queen Elizabeth II Park in Christchurch, Athletics at the 10th British New Zealand between 25 January and 2 February. Athletes Commonwealth Games competed in 37 events — 23 for men and 14 for women. Contents Medal summary Men Women Medal table The QE II Park was purpose-built for the 1974 Games. Participating nations Dates 25 January – 2 References February 1974 Host city Christchurch, New Medal summary Zealand Venue Queen Elizabeth II Park Men Level Senior Events 37 Participation 468 athletes from 35 nations Records set 1 WR, 18 GR ← 1970 Edinburgh 1978 Edmonton → 1974 British Commonwealth Games https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Athletics_at_the_1974_British_Commonwealth_Games 1/6 28/4/2020 Athletics at the 1974 British Commonwealth Games - Wikipedia Event Gold Silver Bronze 100 metres Don John Ohene 10.38 10.51 10.51 (wind: +0.8 m/s) Quarrie Mwebi Karikari 200 metres Don George Bevan 20.73 20.97 21.08 (wind: -0.6 m/s) Quarrie Daniels Smith Charles Silver Claver 400 metres 46.04 46.07 46.16 Asati Ayoo Kamanya John 1:43.91 John 800 metres Mike Boit 1:44.39 1:44.92 Kipkurgat GR Walker Filbert 3:32.16 John Ben 1500 metres 3:32.52 3:33.16 Bayi WR Walker Jipcho Ben 13:14.4 Brendan Dave 5000 metres 13:14.6 13:23.6 Jipcho GR Foster Black Dick Dave Richard 10,000 metres 27:46.40 27:48.49 27:56.96 Tayler Black Juma Ian 2:09:12 Jack Richard Marathon 2:11:19 -

USATF Cross Country Championships Media Handbook

TABLE OF CONTENTS NATIONAL CHAMPIONS LIST..................................................................................................................... 2 NCAA DIVISION I CHAMPIONS LIST .......................................................................................................... 7 U.S. INTERNATIONAL CROSS COUNTRY TRIALS ........................................................................................ 9 HISTORY OF INTERNATIONAL CHAMPIONSHIPS ........................................................................................ 20 APPENDIX A – 2009 USATF CROSS COUNTRY CHAMPIONSHIPS RESULTS ............................................... 62 APPENDIX B –2009 USATF CLUB NATIONAL CHAMPIONSHIPS RESULTS .................................................. 70 USATF MISSION STATEMENT The mission of USATF is to foster sustained competitive excellence, interest, and participation in the sports of track & field, long distance running, and race walking CREDITS The 30th annual U.S. Cross Country Handbook is an official publication of USA Track & Field. ©2011 USA Track & Field, 132 E. Washington St., Suite 800, Indianapolis, IN 46204 317-261-0500; www.usatf.org 2011 U.S. Cross Country Handbook • 1 HISTORY OF THE NATIONAL CHAMPIONSHIPS USA Track & Field MEN: Year Champion Team Champion-score 1954 Gordon McKenzie New York AC-45 1890 William Day Prospect Harriers-41 1955 Horace Ashenfelter New York AC-28 1891 M. Kennedy Prospect Harriers-21 1956 Horace Ashenfelter New York AC-46 1892 Edward Carter Suburban Harriers-41 1957 John Macy New York AC-45 1893-96 Not Contested 1958 John Macy New York AC-28 1897 George Orton Knickerbocker AC-31 1959 Al Lawrence Houston TFC-30 1898 George Orton Knickerbocker AC-42 1960 Al Lawrence Houston TFC-33 1899-1900 Not Contested 1961 Bruce Kidd Houston TFC-35 1901 Jerry Pierce Pastime AC-20 1962 Pete McArdle Los Angeles TC-40 1902 Not Contested 1963 Bruce Kidd Los Angeles TC-47 1903 John Joyce New York AC-21 1964 Dave Ellis Los Angeles TC-29 1904 Not Contested 1965 Ron Larrieu Toronto Olympic Club-40 1905 W.J. -

OLYMPIC GAMES TOKYO October 10 - October 24, 1964

Y.E.A.H. - Young Europeans Active and Healthy OLYMPIC GAMES TOKYO October 10 - October 24, 1964 August and experienced hot weather. The follow- Asia for the first time ing games in 1968 in Mexico City also began in October. The 1964 Summer Olympics, officially known as the Games of the XVIII Olympiad ( Dai J ūhachi-kai Orinpikku Ky ōgi Taikai ), were held in Tokyo , Japan , from October 10 to 24, 1964. Tokyo had been awarded the organization of the 1940 Summer Olympics , but this honor was subsequently passed to Helsinki because of Japan's invasion of China , before ultimately being canceled because of World War II . The 1964 Summer Games were the first Olym- pics held in Asia, and the first time South Africa was barred from taking part due to its apartheid system in sports. (South Africa was, however, allowed to compete at the 1964 Summer Paral- ympics , also held in Tokyo, where it made its Paralympic Games debut .) Tokyo was chosen as the host city during the 55th IOC Session in West Germany, on May 26, 1959. These games were also the first to be telecast internationally without the need for tapes to be flown overseas, as they had been for the 1960 Olympics four years earlier. The games were The 1964 Olympics were also the last to use a telecast to the United States using Syncom 3, the traditional cinder track for the track events. A first geostationary communication satellite, and smooth, synthetic, all-weather track was used for from there to Europe using Relay 1 . -

1 Athletics Kenya and International Calendar Of

ATHLETICS KENYA AND INTERNATIONAL CALENDAR OF EVENTS FOR THE YEAR 2016/2017 SEASON. NOVEMBER 2016 5th 1st A.K Cross Country Series Nairobi KEN 5th Baringo Half Marathon Kabarnet KEN 6th TSC New York Marathon New York USA 6th Shangai International Marathon Shanghai CHN 12th Tegla Loroupe 10Km Peace Run Kapenguria KEN 12th 2nd A.K Cross Country Series Trans-Mara KEN 13th KASS Marathon Eldoret KEN 13th Saitama International Marathon Saitama JPN 13th Marathon des Alpes-Maritimes Nice Cannes Nice FRA 13th Cross de Atapuerca -IAAF Cross Country Permit Meetings Burgos ESP 13th Vodafone Istanbul Marathon Istanbul TUR 13th BDL Beirut Marathon Beirut LIB 19th 3rd Premium A.K Cross Country Series Nyandarua TTI KEN 20th Semi- Marathon de Boulogne Billancourt Christian Granger Boulogne FRA 20th Maraton Valencia Trinidad Alfonso Valencia ESP 20th Airtel Delhi Half Marathon Delhi IND 26th Tusky’s Mattress Wareng Cross Country Eldoret KEN 27th Cross Internacional de la Constitucion de Alcobendas -IAAF Alcobendas ESP Cross Country Permit Meetings DECEMBER 2016 1st World Aids Marathon Kisumu KEN 3rd 4th Premium A.K Cross Country Series Iten KEN 4th 70th Fukuoka International Open Marathon Championships Fukuoka JPN 4th Standard Chartered Marathon Singapore Singapore SIN 6th Campaccio-International Cross Country-IAAF Cross San Giorgio su ITA Country Permit Meetings Legnano 8th A.K Gala Nairobi KEN 11th Imenti 15Km Road Race Nkubu - Meru KEN 10th 5th Athletics Kenya Cross Country Series Kapsokwony KEN 11th Guangzhou Marathon Guangzhou CHN 14th IAAF Antrim