American Primacy and the Global Media

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ITW2018 Study Groups

ITW2018 Study groups FINAL REPORTS CONTENTS SG1 Medical applications of particle physics 3 SG2 Particle accelerators 6 SG3 Particle detectors 10 SG4 Computing in particle physics 14 SG5 Data analysis in particle physics 21 SG6 Antimatter research 27 SG7 Engineering in particle physics 30 SG8 Astroparticle physics 35 SG9 Exotic physics 38 Geneva, August 2018 | indico.cern.ch/e/ITW2018 $2 SG1 | Medical applications of particle physics Nnana Thomas1, Ali Hassan2, László Varnai3, Sonia López Moreno4, Fran Cortés Ortega5 1 The apostolic missions schools, Kano, Nigeria | [email protected] 2 Angels International College, Faisalabad, Pakistan | [email protected] 3 Padanyi, Veszprem, Hungary | [email protected] 4 IES Arcipreste de Hita, Azuqueca de Henares (Guadalajara), Spain | [email protected] 5 Laude BSV, Vila-real (Castellón), Spain | [email protected] Curriculum & classroom connections Nigeria Pakistan Hungary Spain Classroom Medical connexions applications named throughout the curriculum and studied the previous years before going to the University. 12-13 years old Atom, Nucleus, X- Atoms, nucleus, -Atom, nucleus, -Cancer Ray, X-tube. subatomic particles subatomic particles Medical Application (p, e, n). Discovery (p, e, n), nuclear 13-14 years old of X-Ray. Safety of protons, physics, X-rays, -Atomic models, Precautions neutrons and radioactivity and electron, neutron. Electrons, , decays, -Medical Radioactivity and photoelectric effect, applications 14-15 years old decays, Alpha, weak interactions. -Cancer, DNA Beta and Gamma Particles and their 15-16 years old properties, Nuclear -Mutations and Fission and Fusion cancer, DNA reactions. 16-17 years old -Electrostatic forces $3 17-18 years old Atom, Nucleus, X-Ray and Its -Medical - Mutations and Proton,X-Ray, medical applications (X- cancer. -

Queens' College Record 2009

QUEENS’ COLLEGE RECORD • 2009 Queens’ College Record 2009 The Queens’ College Record 2009 Table of Contents 2 The Fellowship (March 2009) The Sporting Record 38 Captains of the Clubs 4 From the President 38 Reports from the Sports Clubs The Society The Student Record 5 The Fellows in 2008 44 The Students 2008 9 Retirement of Professor John Tiley 44 Admissions 9 Book Review 45 Director of Music 10 Thomae Smithi Academia 45 Dancer in Residence 10 Douglas Parmée, Fellow 1947–2008 46 Around the World and Back: A Hawk-Eye View 11 The Very Revd Professor Henry Chadwick 47 On the Hunt for the Cave of Euripides Fellow 1946–59, Honorary Fellow 1959–2008 48 Five Weeks in Japan 13 Richard Hickox, Honorary Fellow 1996–2008 49 Does Anyone Know the Way to Mongolia? 50 South Korea – As Diverse as its Kimchi 14 The Staff 51 Losing the Granola 52 Streetbite 2008 The Buildings 52 Distinctions and Awards 15 The Fabric 2008 54 Reports from the Clubs and Societies 16 The Chapel The Academic Record 62 Learning to Find Our Way Through Economic Turmoil 18 The Libraries 64 War in Academia 19 Newly-Identified Miniatures from the Old Library The Development Record 23 The Gardens 66 Donors to Queens’ 2008 The Historical Record The Alumni Record 24 1209 And All That 69 Alumni Association AGM 26 A Bohemian Mystery 69 News of Members 29 Robert Plumptre – 18th-Century President of Queens’ 80 The 2002 Matriculation Year and Servant of the House of Yorke 81 Deaths 33 Abraham v Abraham 82 Obituaries 37 Head of the River 1968 88 Forthcoming Alumni Events The front cover photograph shows the Martyrdom of St Lucy from a miniature attributed to Pacino di Bonaguida, from the Old Library. -

Outward Thinking

ISSUE 19 MICHAELMAS 2004 Outward Thinking From the Master Our academic year As part of its commitment to supporting world-class research started sadly with the and scholarship, Univ is reinforcing its longstanding connection death of Clare Drury, with philosophical thinking about law. our Senior Tutor since Thanks to the generous support of Univ Old Members, the College 2000. I have written is launching a programme of graduate studentships and visiting elsewhere about Clare fellowships in the field, and will soon be providing a physical home to and my address at her the Oxford Centre for Ethics and Philosophy of Law (CEPL). CEPL was funeral will be printed Professor John Gardner in next year’s Record. founded in 2002 as a collaboration between the three “Merton So suffice it to say here Street” colleges: Univ, Corpus, and Merton. It is jointly directed by John Broome of Corpus Lord Butler that her death was a of Brockwell (Professor of Moral Philosophy) and Univ’s own John Gardner (Professor of Jurisprudence). huge loss and major CEPL brings together moral and legal philosophers from all over the world. In addition to source of sadness in our College family. weekly speaker meetings, this year’s special events include a workshop on the philosophy of We were fortunate in recruiting as human rights at UNESCO in Paris, a conference at Univ on the law and ethics of complicity, Clare’s successor Dr Anne Knowland, and a colloquium on ‘aggregation’ (how to count people’s interests) to be led by Univ’s previously Divisional Secretary of the Donnelley JRF, Iwao Hirose. -

Pocket Product Guide 2006

THENew Digital Platform MIPTV 2012 tm MIPTV POCKET ISSUE & PRODUCT OFFILMGUIDE New One Stop Product Guide Search at the Markets Paperless - Weightless - Green Read the Synopsis - Watch the Trailer BUSINESSC onnect to Seller - Buy Product MIPTVDaily Editions April 1-4, 2012 - Unabridged MIPTV Product Guide + Stills Cher Ami - Magus Entertainment - Booth 12.32 POD 32 (Mountain Road) STEP UP to 21st Century The DIGITAL Platform PUBLISHING Is The FUTURE MIPTV PRODUCT GUIDE 2012 Mountain, Nature, Extreme, Geography, 10 FRANCS Water, Surprising 10 Francs, 28 Rue de l'Equerre, Paris, Delivery Status: Screening France 75019 France, Tel: Year of Production: 2011 Country of +33.1.487.44.377. Fax: +33.1.487.48.265. Origin: Slovakia http://www.10francs.f - email: Only the best of the best are able to abseil [email protected] into depths The Iron Hole, but even that Distributor doesn't guarantee that they will ever man- At MIPTV: Yohann Cornu (Sales age to get back.That's up to nature to Executive), Christelle Quillévéré (Sales) decide. Office: MEDIA Stand N°H4.35, Tel: + GOOD MORNING LENIN ! 33.6.628.04.377. Fax: + 33.1.487.48.265 Documentary (50') BEING KOSHER Language: English, Polish Documentary (52' & 92') Director: Konrad Szolajski Language: German, English Producer: ZK Studio Ltd Director: Ruth Olsman Key Cast: Surprising, Travel, History, Producer: Indi Film Gmbh Human Stories, Daily Life, Humour, Key Cast: Surprising, Judaism, Religion, Politics, Business, Europe, Ethnology Tradition, Culture, Daily life, Education, Delivery Status: Screening Ethnology, Humour, Interviews Year of Production: 2010 Country of Delivery Status: Screening Origin: Poland Year of Production: 2010 Country of Western foreigners come to Poland to expe- Origin: Germany rience life under communism enacted by A tragicomic exploration of Jewish purity former steel mill workers who, in this way, laws ! From kosher food to ritual hygiene, escaped unemployment. -

Dream Scene in January 2015

Issue no. 93, 1st of November 2014. Bienvenido a todos and welcome to the November edition. The wether during October has been brilliant. Blue skies and warm temperatures, often in the low 30’s. However the evenings are now beginning to get much cooler. So, if you are coming over soon, bring that cardigan or jumper. What has also been noticeable during October is the abundance of flies. After more than 10 years on the Orihuela Costa I cannot recall seeing so many and they have often been very annoying. Some people also seem to attract the midges and mosquito and their bites, while others remain untouched. There has been an increase in bites from the Tiger mosquito - Aedes albopictus, photo. These can be very painful and are usually accompanied by large swollen areas of flesh. It is important that you check around your property and throw out any stagnant water, where these pests can breed. With a whole raft of elections due next year, the politicians are already preparing their ground work and handing out promises like sweets at fiestas. PM Rajoy gave a speech to the PP party faithful in Murcia last Sunday. It made me laugh! He referred to the corruption in Spain as ‘some little things’ and does not reflect what Spain is. Well Mr. Prime Minister, lets take a quick look! First of all their is a former party treasurer of your own party, Luis Barcenas, who has been in custody since June 2013 and is trying to explain €23 million in a Swiss bank account and payments to PP politicians; then there is the long running Gürtel case which involves illicit activities related to PP party funding and the award of contracts by local/regional government in Valencia, the Community of Madrid and elsewhere - many millions!; the Brujal case in Orihuela where 35, including two former PP mayors, have been charged. -

Brexit - Deal Or No Deal – What Does This Mean for Your IP?

TRADE MARKS Brexit - Deal or no deal – what does this mean for your IP? In March this year the UK and the European Commission issued a joint working document which includes guidance on IP issues post Brexit which Barker Brettell commented on here. In that document there is provision for the automatic extension of any granted EU rights to the UK post Brexit and for an application process for the continuation of any pending EU applications into additional UK applications. This joint working document made it clear that although the UK is due to leave the European Union on the 29th March 2019, provided that the UK and the EU arrive at an exit agreement there will be a transition period through to the 31st December 2020, throughout which EU law will still apply within the UK. On the 24th September, mindful of the increasing speculation regarding a ‘no deal’ Brexit, the UK government issued a number of technical notes. The UK government made it clear that it will make unilateral provision for the continuation of all EU rights in the UK if no deal is struck and that those provisions will mirror the joint working document. In such a ‘no deal’ scenario however, the transitional provisions taking us to the end of 2020 will not apply. Rights would be impacted as of the exit date. It could be ‘business as usual’ for IP until the end of 2020 and indeed patents are unaffected by Brexit, however businesses need to be aware of the implications going forward and to consider what action can be taken now to minimise any risks and potential costs. -

Risk Aversion: Deal Or No Deal? Outline

Risk Aversion: Deal or No Deal? Outline ¨ Risk Attitude and Expected Return ¨ Game: Deal or No Deal? Risk Attitude and Expected Return ¨ In each pair, please choose an asset out of the two options. ¨ A: Option 1: 50%: 100; 50%: 50 vs. Option 2: 100%: 60 ¨ B: Option 1: 50%: 100; 50%: 50 vs. Option 2: 100%: 70 ¨ C: Option 1: 50%: 100; 50%: 50 vs. Option 2: 100%: 75 ¨ D: Option 1: 50%: 100; 50%: 50 vs. Option 2: 100%: 80 ¨ E: Option 1: 50%: 100; 50%: 50 vs. Option 2: 100%: 90 Risk Attitude and Expected Return ¨ Expected value n Expected Value = ∑Pi ⋅ X i i=1 Risk Attitude and Expected Return ¨ Risk Aversion: a dislike of uncertainty 1. If your choice is (2,2,2,2,2), (1,2,2,2,2), (1,1,2,2,2), you are risk-averse. 2. If your choice is (1,1,1,1,1), (2,2,2,2,1) or (2,2,2,1,1), you are risk-loving. 3. If your choice is (1,1,1or2,2,2), you are risk-neutral. Indifferent Game: Deal or No Deal ¨ I am sure most of you have heard about the TV show – Deal or No Deal. If you haven’t, the youtube videos below give you an idea of how this game is played: ¨ Deal or No Deal (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hmZFHjQfx-o&feature=related) ¨ First 1 million winner (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gg7vtTCAkbY&feature=related) Game: Deal or No Deal ¨ We are going to play a simplified version of the game. -

Limitations on Copyright Protection for Format Ideas in Reality Television Programming

For exclusive use of MLRC members and other parties specifically authorized by MLRC. © Media Law Resource Center, Inc. LIMITATIONS ON COPYRIGHT PROTECTION FOR FORMAT IDEAS IN REALITY TELEVISION PROGRAMMING By Kent R. Raygor and Edwin Komen* * Kent R. Raygor and Edwin Komen are partners in the Entertainment, Media, and Technology Group in the Century City, California and Washington, D.C. offices, respectively, of Sheppard Mullin Richter & Hampton LLP. The authors thank Ben Aigboboh, an associate in the Century City office, for his assistance with this article. 97 For exclusive use of MLRC members and other parties specifically authorized by MLRC. © Media Law Resource Center, Inc. LIMITATIONS ON COPYRIGHT PROTECTION FOR FORMAT IDEAS IN REALITY TELEVISION PROGRAMMING I. INTRODUCTION Television networks constantly compete to find and produce the next big hit. The shifting economic landscape forged by increasing competition between and among ever-proliferating media platforms, however, places extreme pressure on network profit margins. Fully scripted hour-long dramas and half-hour comedies have become increasingly costly, while delivering diminishing ratings in the key demographics most valued by advertisers. It therefore is not surprising that the reality television genre has become a staple of network schedules. New reality shows are churned out each season.1 The main appeal, of course, is that they are cheap to make and addictive to watch. Networks are able to take ordinary people and create a show without having to pay “A-list” actor salaries and hire teams of writers.2 Many of the most popular programs are unscripted, meaning lower cost for higher ratings. Even where the ratings are flat, such shows are capable of generating higher profit margins through advertising directed to large groups of more readily targeted viewers. -

University Challenge Series 24 (2017) Contestant Application Form

UNIVERSITY CHALLENGE SERIES 24 (2017) CONTESTANT APPLICATION FORM PLEASE READ THIS APPLICATION FORM, INCLUDING THE TERMS AND CONDITIONS, VERY CAREFULLY BEFORE COMPLETING AND SIGNING. 1. You are applying to be considered as a contestant in the programme entitled “UNIVERSITY CHALLENGE SERIES 24” (the “Programme”, “University Challenge”) which ITV Studios Limited (“we”, “us”, “our”) intends but does not undertake to produce for initial transmission by the BBC (the “Broadcaster”). 2. The Programme is a quiz programme in which two teams of university students compete against each other in answering general knowledge questions on a wide range of subjects. 3. Please fill out this entire application form (the “Application Form”) legibly using dark-coloured ink. You must fill out the entire Application Form. Do not leave any question unanswered. If any question is not applicable to you, please write “N/A” in the space provided. If you run out of space answering any question, please use the back of the form and reference the question(s) accordingly. 4. Each team member and the reserve member is required to read, complete and sign an Application Form on an individual basis. 5. The Application Test should be completed by all four team members and the reserve member collectively and returned together with the completed Application Forms. 6. Please note that Application Forms must not be returned by email, as they require your signatures. 7. Return the completed Application Forms and recent photographs for each team member and the reserve member, plus the Application Test, as a collective submission in the FREEPOST envelope provided to be received by Wednesday 23 November 2016. -

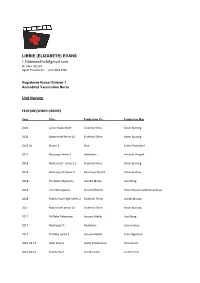

EVANS Libbie CV

LIBBIE (ELIZABETH) EVANS E: [email protected] M: 0409 195 247 Agent: Freelancers +613 9682 2722 Registered Nurse Division 1 Accredited Vaccination Nurse Unit Nursing FEATURE/SERIES CREDITS Year Title Production Co. Production Mgr 2020 Junior Masterchef Endemol Shine Karen Bunting 2020 Masterchef Series 12 Endemol Shine Karen Bunting 2019-20 Bloom 2 Stan Esther Rodewald 2019 Mustangs Series 3 Matchbox Amanda WrayeE 2018 Masterchef Series 11 Endemol Shine Karen Bunting 2018- Mustangs FC Series 2 Mustangs Pty Ltd Amanda Wray 2018- The Blake Mysteries Gambit Media Lisa Wang 2018 The InBestigators Gristmill/Netfix Peter Muston (additional days) 2018- Family Food Fight Series 2 Endemol Shine Lyndal Murray 2017 Masterchef Series 10 Endemol Shine Karen Bunting 2017 Dr Blake Telemovie January Media Lisa Wang 2017 Mustangs FC Matchbox Jane Lindsey 2017 Dr Blake series 5 January Media Elisa Argentisio 2016-04-12 Little Acorns Guilty Productions Tom Davies 2016-04-12 Family Feud Ten Network Caitlin Finch Year Title Production Co. Production Mgr. 2015 Dr Blake Series 4 January Media Ross Allsop 2015 Jack Irish Essential M Jane Sullivan 2015 Winners and Losers Channel 7 Naomi Mulholland 2015- Childhoods’ End Haypop Pty Ltd Wade Savage 2014 Masterchef Shine Australia Megan Brock 2014 The Secret River Ruby Entertainment Lesley Parker 2014 Gallipoli Endemol Australia Deborah Glover 2014 Masterchef Shine Australia Michaela Sampson 2013 Dr Blake Series 2 January Productions Ross Allsop/ Naomi Mulholland 2013 Worst Year of My Life Again Worst Year Productions -

FOREVER: KEELE for Keele People Past and Present Issue 8//2013

FOREVER: KEELE For Keele People Past and Present Issue 8//2013 Keele University Contents Who’s Who in the Alumni P1 P6 and Development Team P2 P4 Dawn-Marie Beeston: I graduated from Keele in 2011. I enjoyed my time here so much I didn’t want to leave and last year I was fortunate enough to get a position in the Alumni and Development team. When I’m not at Keele I spend my time with my horses, dogs and family. P8 P10 John Easom: I studied at Keele back in 1980-1981. After twenty years in the Civil Service I moved on to international trade development and then finally got back to Keele in P12 P14 2005. This is the best job of my life. If I could do it wearing skates my joy would be complete. Union Square Lives Fireworks and lasers lit up the Students’ Union Building and the sky above as alumni, students, staff and local residents gathered on 28 November 2012 to witness the official lighting of the ‘Forest of Light’ P18 P32 at the heart of the campus. The 50 slim gleaming stainless steel columns – each Emma Gregory: one representing a Class of Alumni since I started with Keele in 2012. I trained as a 1962 encircle a central plinth inscribed Vet Nurse but being allergic to fur created with a phrase echoing our founder, Lord a bit of a barrier! After four years in the A D LIndsay of Birker: “Search for Truth in Civil Service, it was time for a complete the Company of Friends”. -

Clare News D Spring/Summer 2012 E

9 2 N O I T I CLARE NEWS D SPRING/SUMMER 2012 E University Challenge History repeats itself Summer Blues Rising Talent Six Questions Clare sport in Harriet Muller Dr Alice Welbourn Olympic year Artist HIV awareness CLARE NEWS I Alumni News Alumni News I CLARE NEWS WHERE ARE THEY NOW? University Challenge – drama of the quarter finals Clare’s Olympian professor Paul Klenerman 1982 BA Medical Sciences lare’s 2012 and 1973 University Challenge Cteams met similar success in their quest Then for glory: they stormed through to the Fenced for the British Olympic quarter finals but lost out to the eventual team at Los Angeles 1984 as a winners Manchester University and Trinity College, Cambridge, respectively. Clare undergraduate This year’s team were captain Jonathan Burley (Natural Sciences), Daniel Janes Now (History), Kris Cao (Mathematics) and Professor of Immunology and Jonathan Foxwell (Natural Sciences). medical researcher, Oxford Highlights included walking to their University, trialling vaccines for places on the studio set in Manchester to Hepatitis C the Rocky theme music . Their mascot was Then Paul chose Clare because he “liked Question from 1973: the look of it” and it had a reputation for Who was the French friendliness and being good all-round. He commander at Trafalgar? l Today’s team – Kris Cao, arrived as the GB Under-20 Fencing Daniel Janes, Jonathan Burley Question from 2012: Champion, having taken up the sport “to l David Holmes and Jonathan Foxwell give it a go” at City of London School. “I Etymologically unrelated, didn’t win a single fight early on and got what short name links a David Holmes (1972): “The radical ever our opponents appeared to be doing (1972) semi-retired investment manager; thrashed by bigger kids, but must have French départment, named students of the 70s, sporting pro-Marxist too well.