University Challenge

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Queens' College Record 2009

QUEENS’ COLLEGE RECORD • 2009 Queens’ College Record 2009 The Queens’ College Record 2009 Table of Contents 2 The Fellowship (March 2009) The Sporting Record 38 Captains of the Clubs 4 From the President 38 Reports from the Sports Clubs The Society The Student Record 5 The Fellows in 2008 44 The Students 2008 9 Retirement of Professor John Tiley 44 Admissions 9 Book Review 45 Director of Music 10 Thomae Smithi Academia 45 Dancer in Residence 10 Douglas Parmée, Fellow 1947–2008 46 Around the World and Back: A Hawk-Eye View 11 The Very Revd Professor Henry Chadwick 47 On the Hunt for the Cave of Euripides Fellow 1946–59, Honorary Fellow 1959–2008 48 Five Weeks in Japan 13 Richard Hickox, Honorary Fellow 1996–2008 49 Does Anyone Know the Way to Mongolia? 50 South Korea – As Diverse as its Kimchi 14 The Staff 51 Losing the Granola 52 Streetbite 2008 The Buildings 52 Distinctions and Awards 15 The Fabric 2008 54 Reports from the Clubs and Societies 16 The Chapel The Academic Record 62 Learning to Find Our Way Through Economic Turmoil 18 The Libraries 64 War in Academia 19 Newly-Identified Miniatures from the Old Library The Development Record 23 The Gardens 66 Donors to Queens’ 2008 The Historical Record The Alumni Record 24 1209 And All That 69 Alumni Association AGM 26 A Bohemian Mystery 69 News of Members 29 Robert Plumptre – 18th-Century President of Queens’ 80 The 2002 Matriculation Year and Servant of the House of Yorke 81 Deaths 33 Abraham v Abraham 82 Obituaries 37 Head of the River 1968 88 Forthcoming Alumni Events The front cover photograph shows the Martyrdom of St Lucy from a miniature attributed to Pacino di Bonaguida, from the Old Library. -

Outward Thinking

ISSUE 19 MICHAELMAS 2004 Outward Thinking From the Master Our academic year As part of its commitment to supporting world-class research started sadly with the and scholarship, Univ is reinforcing its longstanding connection death of Clare Drury, with philosophical thinking about law. our Senior Tutor since Thanks to the generous support of Univ Old Members, the College 2000. I have written is launching a programme of graduate studentships and visiting elsewhere about Clare fellowships in the field, and will soon be providing a physical home to and my address at her the Oxford Centre for Ethics and Philosophy of Law (CEPL). CEPL was funeral will be printed Professor John Gardner in next year’s Record. founded in 2002 as a collaboration between the three “Merton So suffice it to say here Street” colleges: Univ, Corpus, and Merton. It is jointly directed by John Broome of Corpus Lord Butler that her death was a of Brockwell (Professor of Moral Philosophy) and Univ’s own John Gardner (Professor of Jurisprudence). huge loss and major CEPL brings together moral and legal philosophers from all over the world. In addition to source of sadness in our College family. weekly speaker meetings, this year’s special events include a workshop on the philosophy of We were fortunate in recruiting as human rights at UNESCO in Paris, a conference at Univ on the law and ethics of complicity, Clare’s successor Dr Anne Knowland, and a colloquium on ‘aggregation’ (how to count people’s interests) to be led by Univ’s previously Divisional Secretary of the Donnelley JRF, Iwao Hirose. -

University Challenge Series 24 (2017) Contestant Application Form

UNIVERSITY CHALLENGE SERIES 24 (2017) CONTESTANT APPLICATION FORM PLEASE READ THIS APPLICATION FORM, INCLUDING THE TERMS AND CONDITIONS, VERY CAREFULLY BEFORE COMPLETING AND SIGNING. 1. You are applying to be considered as a contestant in the programme entitled “UNIVERSITY CHALLENGE SERIES 24” (the “Programme”, “University Challenge”) which ITV Studios Limited (“we”, “us”, “our”) intends but does not undertake to produce for initial transmission by the BBC (the “Broadcaster”). 2. The Programme is a quiz programme in which two teams of university students compete against each other in answering general knowledge questions on a wide range of subjects. 3. Please fill out this entire application form (the “Application Form”) legibly using dark-coloured ink. You must fill out the entire Application Form. Do not leave any question unanswered. If any question is not applicable to you, please write “N/A” in the space provided. If you run out of space answering any question, please use the back of the form and reference the question(s) accordingly. 4. Each team member and the reserve member is required to read, complete and sign an Application Form on an individual basis. 5. The Application Test should be completed by all four team members and the reserve member collectively and returned together with the completed Application Forms. 6. Please note that Application Forms must not be returned by email, as they require your signatures. 7. Return the completed Application Forms and recent photographs for each team member and the reserve member, plus the Application Test, as a collective submission in the FREEPOST envelope provided to be received by Wednesday 23 November 2016. -

FOREVER: KEELE for Keele People Past and Present Issue 8//2013

FOREVER: KEELE For Keele People Past and Present Issue 8//2013 Keele University Contents Who’s Who in the Alumni P1 P6 and Development Team P2 P4 Dawn-Marie Beeston: I graduated from Keele in 2011. I enjoyed my time here so much I didn’t want to leave and last year I was fortunate enough to get a position in the Alumni and Development team. When I’m not at Keele I spend my time with my horses, dogs and family. P8 P10 John Easom: I studied at Keele back in 1980-1981. After twenty years in the Civil Service I moved on to international trade development and then finally got back to Keele in P12 P14 2005. This is the best job of my life. If I could do it wearing skates my joy would be complete. Union Square Lives Fireworks and lasers lit up the Students’ Union Building and the sky above as alumni, students, staff and local residents gathered on 28 November 2012 to witness the official lighting of the ‘Forest of Light’ P18 P32 at the heart of the campus. The 50 slim gleaming stainless steel columns – each Emma Gregory: one representing a Class of Alumni since I started with Keele in 2012. I trained as a 1962 encircle a central plinth inscribed Vet Nurse but being allergic to fur created with a phrase echoing our founder, Lord a bit of a barrier! After four years in the A D LIndsay of Birker: “Search for Truth in Civil Service, it was time for a complete the Company of Friends”. -

Clare News D Spring/Summer 2012 E

9 2 N O I T I CLARE NEWS D SPRING/SUMMER 2012 E University Challenge History repeats itself Summer Blues Rising Talent Six Questions Clare sport in Harriet Muller Dr Alice Welbourn Olympic year Artist HIV awareness CLARE NEWS I Alumni News Alumni News I CLARE NEWS WHERE ARE THEY NOW? University Challenge – drama of the quarter finals Clare’s Olympian professor Paul Klenerman 1982 BA Medical Sciences lare’s 2012 and 1973 University Challenge Cteams met similar success in their quest Then for glory: they stormed through to the Fenced for the British Olympic quarter finals but lost out to the eventual team at Los Angeles 1984 as a winners Manchester University and Trinity College, Cambridge, respectively. Clare undergraduate This year’s team were captain Jonathan Burley (Natural Sciences), Daniel Janes Now (History), Kris Cao (Mathematics) and Professor of Immunology and Jonathan Foxwell (Natural Sciences). medical researcher, Oxford Highlights included walking to their University, trialling vaccines for places on the studio set in Manchester to Hepatitis C the Rocky theme music . Their mascot was Then Paul chose Clare because he “liked Question from 1973: the look of it” and it had a reputation for Who was the French friendliness and being good all-round. He commander at Trafalgar? l Today’s team – Kris Cao, arrived as the GB Under-20 Fencing Daniel Janes, Jonathan Burley Question from 2012: Champion, having taken up the sport “to l David Holmes and Jonathan Foxwell give it a go” at City of London School. “I Etymologically unrelated, didn’t win a single fight early on and got what short name links a David Holmes (1972): “The radical ever our opponents appeared to be doing (1972) semi-retired investment manager; thrashed by bigger kids, but must have French départment, named students of the 70s, sporting pro-Marxist too well. -

University Challenge: How Higher Education Can Advance Social

University Challenge: How Higher Education Can Advance Social Mobility University Challenge: How Higher Education Can University Challenge: How Higher Education Can Advance Social Mobility A progress report by the Independent Reviewer on A progress report by the Independent Reviewer on Social Mobility and Child Poverty October 2012 A Social Mobility and Child Poverty October 2012 Contents Foreword and summary 1 Chapter 1 Introduction 11 Chapter 2 Access all areas 19 Chapter 3 Making the grade 27 Chapter 4 Getting ready – reaching out to 33 potential applicants Chapter 5 Getting in – university admissions 45 Chapter 6 Staying in – student retention 59 Chapter 7 Getting on – student outcomes 67 Chapter 8 How government can help 75 Annex Acknowledgements 87 References 89 © Crown copyright 2012 You may reuse this information (not including logos) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence. To view this licence, go to: www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU email: [email protected] Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. If you have an enquiry regarding this publication, please contact: 0845 000 4999 [email protected] This publication is available from www.official-documents.gov.uk and www.cabinetoffice.gov.uk 1 Foreword and summary Rt. Hon. Alan Milburn, Independent Reviewer on Social Mobility and Child Poverty Like so many others of We are blessed in Britain to have a world-leading my generation I was the higher education sector. -

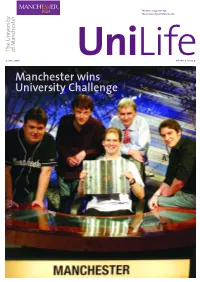

Manchester Wins University Challenge Features Letter from the President

The free magazine for The University of Manchester 5 June, 2006 UniLifeVolume 3 Issue 9 Manchester wins University Challenge Features Letter from the President News Manchester remains top of the popularity league page 5 Profile Professor Klaus Müller-Dethlefs page 12 Feature Hippest show A lot of hard work has been going on over recent Making such choices is difficult at the best in town weeks to produce a draft 2006-07 Budget for of times. But there is an enormous difference recommendation via the Planning and Resources between a budget that is growing and one that page 18 Committee to Finance Committee and the Board is not. When resources are diminishing it is of Governors. extraordinarily difficult to keep aspiration and creativity alive. Even the most ambitious, creative The good news about our 2006-07 budget is that people begin to focus on just keeping things revenue has grown significantly in real terms. going, so the fact that our budget is growing is While reducing our overall deficit as planned, we good news indeed. will have around £75 million more to spend than Contents we had in 2005-06, and more than half of this Yet the truth remains that our Manchester 2015 represents real growth. Research income and fee Agenda will not be realised without even greater revenue are both significantly higher. revenue growth year-in, year-out over the next decade. Without continuing emphasis on growing Budgeting is about managing scarcity. The number 3 News revenue and, (where possible without of initiatives worth pursuing always exceeds the compromising quality) reducing costs, the gap 7 Research resources available. -

University Challenge Campaign Letter

UNIVERSITY CHALLENGE – PROGRAMME ELIGIBILITY REQUIREMENTS University Challenge is a competition for teams of students. WE DRAW YOUR ATTENTION IN PARTICULAR TO ELIGIBILITY REQUIREMENT 3, WHICH SETS OUT THE DEFINITION OF “STUDENT” FOR THE PURPOSES OF UNIVERSITY CHALLENGE. Please note, if the eligibility of any applicant changes then that applicant should immediately notify the University Challenge producer as per the Eligibility Requirements. These are the Eligibility Requirements for University Challenge Series 24 (2017): 1. A team consists of four team members and one reserve member, subject to Eligibility Requirement 10 below. 2. Team members and the reserve member must not have appeared on the televised version of University Challenge for any university or university college on any previous occasion. 3. University Challenge is a competition for teams of students. For the purposes of University Challenge, we are defining a “student” as a person: (a) who has enrolled with a university or university college; and (b) who is following a recognised course of study at that university or university college; and (c) whose final award in respect of that course of study has not yet been communicated by that university or university college. 4. Team members and the reserve member must be available to attend all the recordings of University Challenge on the dates notified to them by the University Challenge producer. 5. At the time of completing the Application forms, and throughout all recording all team members and the reserve member must be students at the UK university or university college which is named on their Application form and which will be named on the desk at which they sit to compete in the studio recordings of University Challenge. -

A New University Challenge 22

PHOTO REDACTED DUE TO THIRD PARTY RIGHTS OR OTHER LEGAL ISSUES PHOTO REDACTED DUE TO THIRD PARTY RIGHTS OR OTHER LEGAL ISSUES PHOTO REDACTED DUE TO THIRD PARTY RIGHTS OR OTHER LEGAL ISSUES A new ‘University Challenge’ PHOTO REDACTED DUE TO THIRD PARTY RIGHTS OR OTHER LEGAL ISSUES Unlocking Britain’s Talent Contents Contents Foreword 1 Section 1 A new ‘University Challenge’ 3 Section 2 Expansion of local and regional HE provision 9 Section 3 Annex A 13 Section 4 Annex B 15 1 Foreword Foreword Higher education is critically important to the future of this country. It can unlock the talents of our people, provide the research and scholarship our economy and society need, and play a critical role in maintaining a competitive and innovative economy. The importance of universities and other higher education providers to the national economy is becoming increasingly well recognised. A local, highquality campus can open up the chance of higher education to young people and adults who might otherwise never think of getting a degree. Higher education now provides the skills and knowledge transfer that enables local businesses to grow and attract new investment to the area. Over and above their contribution to economic regeneration and development, universities and other higher education providers are seen as making a real difference to the cultural life of our towns and cities. So it is not surprising that increasing numbers of towns and cities are seeking to offer higher education. We want to make the process of gaining a higher education campus more open and more transparent. -

Trinity College Chapel Michaelmas Term 2019

TRINITY COLLEGE CHAPEL MICHAELMAS TERM 2019 SPECIAL SERVICES Sunday 6 October 12.00 noon Freshers’ Service followed by a sandwich lunch in the Ante-Chapel Thursday 7 November 6.15 pm Sung Eucharist for the Eve of the Saints and Martyrs of England Sunday 10 November Remembrance Sunday 10.55 am Act of Remembrance & Mattins Address to be given by Wesley Kerr OBE Monday 11 November 10.55 am Remembrance Day Observance Gather in Chapel to observe the two-minute silence Sunday 1 December 6.15 pm Advent Carol Service This service is ticketed. Invitations will be circulated to Fellows, staff and students at the beginning of November; members of the congregation wishing to attend should email the Chapel Secretary. CHRISTMAS SERVICES Saturday 14 December 4.00 pm Christingle with Carols an interactive service for children of all ages, featuring the Choristers of Little St Mary’s Church Tuesday 24 December 3.30 pm Christmas Eve Crib Service a service for young children at which we hear the Christmas story and assemble the nativity scene Wednesday 25 December 9.30 am Christmas Day Eucharist a traditional service of hymns, readings and Holy Communion with a sermon by the Dean of Chapel SUNDAY EVENSONG 6.15 pm WHAT ARE WE DOING AT EVENSONG? 13 October Confessing The Dean of Chapel 20 October Hearing the Psalms The Revd Dr Megan Daffern Ely Diocesan Director of Ordinands and Vocations 27 October Hearing the Scriptures The Revd Dr Paul Dominiak Vice-Principal of Westcott House, University of Cambridge 3 November Singing the Canticles The -

Alumni Challenge University Challenge a Total of 15 Times, the Cerebral Mettle of Keble Alumni Was Tested During the 2017/18 Including the First-Ever Series in 1963

the Anna Barona brithe newsletter for keblec alumni • ki ss u e 6 5 • hilary term 2 0 1 8 • www.keble.ox.ac.uk Past Keble Teams Keble College has appeared on Alumni Challenge University Challenge a total of 15 times, The cerebral mettle of Keble Alumni was tested during the 2017/18 including the first-ever series in 1963. University Challenge Christmas Special. Unfazed, the Keble team 1963 Quarterfinal defeated Durham, St John’s College, Cambridge, and the University of R Smith (1961), R Carden (1961), C Hoile (1961), B Fawcett (1961). Reading to become overall champions. Katy Brand, who captained the team, tells us about the experience. 1972 Final C Wickham (1968), M Sheppard (1968), E Owen (1971), W Challis (1970). 1975 Winners K Barnard (1972), G Drahun (1971), W Charlsworth (1972), T Lemmer (1972). 1975 Students vs Dons Special 1978 E Watson (1976), P Noake (1976), C Lock (1974), M Slaughter (1976). 1981 No data available. 1987 Winners G Smith (1985), S Follows (1985), S Brindle (1981), J Goodfellow (1983). 1987 International Special Otago, NZ vs Keble Paul Johnson (1985), Frank Cottrell-Boyce (1979), Katy Brand (1997), Anne-Marie 1992 Pro-Celebrity Special Imafidon (2006) and reserve David Bailey (1982). R Arthur (1990), J McDonagh (1991), A Newman (1990), A Hallsworth (1992). When I was asked to participate in the the Manchester studio and the positive vibe 1995 2017 University Challenge Christmas continued as our winning streak began to R Doig (1992), R Cowan (1993), Special, I have to admit, I hesitated. I am an take on legendary proportions. -

University Challenge 2013 the Trailblazers’ Higher Education Report Report 13 of the Inclusion Now Series, October 2013

University Challenge 2013 The Trailblazers’ Higher Education report Report 13 of the Inclusion Now Series, October 2013 Trailblazers Young Campaigners’ Network 2 Trailblazers Young Campaigners’ Network This report has been researched and compiled by Trailblazers ambassadors: Hannah-Lou Blackall – East of England Hayleigh Barclay – Scotland Paul Peterson – East of England Catherine Gillies – Scotland Niall Gillies – Scotland Jon Hollowell – East Midlands Lauramechelle Stewart – Scotland Nirav Shah – East Midlands Mathy Selvakumaran – East Midlands Jonathan Bishop – Wales Ross Taylor – Wales Luke Baily – London Lauren West – Wales Nicky Baker – London Krishna Talsania – London Matilda Ibini – London Elora Kadir – London Sulaiman Khan – London Kushal Pandya – London Rupert Prokofiev – London Maddy Rees – London Rikin Shah – London Mindi Virdee – London Tanvi Vyas – London Carolyn Bean – North East Jennifer Gallacher – North East Cath McNicol – North East Sam Smith – North East Catherine Alexander – North West Miro Griffiths – North West Rupy Kaur – North West Carrie-Ann Lightley – North West Valerie Klin-Barefoot – South East Joshua Langley – South East Laura Merry – South East Mike Moorwood – South East Matthew Naismith – South East Dean Yorke – South East Sarah Croft – South West Samuel Dunlop – South West Get involved Zoe Hallam – South West Take action, campaign, learn new skills. Interested Steve Ledbrook- South West in becoming a Trailblazer? We always welcome Fleur Perry – South West people to our thriving campaigning community. Harriet