Agricultural Products

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Berkeley Art Museum·Pacific Film Archive W in Ter 20 19

WINTER 2019–20 WINTER BERKELEY ART MUSEUM · PACIFIC FILM ARCHIVE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PROGRAM GUIDE ROSIE LEE TOMPKINS RON NAGLE EDIE FAKE TAISO YOSHITOSHI GEOGRAPHIES OF CALIFORNIA AGNÈS VARDA FEDERICO FELLINI DAVID LYNCH ABBAS KIAROSTAMI J. HOBERMAN ROMANIAN CINEMA DOCUMENTARY VOICES OUT OF THE VAULT 1 / 2 / 3 / 4 / 5 / 6 CALENDAR DEC 11/WED 22/SUN 10/FRI 7:00 Full: Strange Connections P. 4 1:00 Christ Stopped at Eboli P. 21 6:30 Blue Velvet LYNCH P. 26 1/SUN 7:00 The King of Comedy 7:00 Full: Howl & Beat P. 4 Introduction & book signing by 25/WED 2:00 Guided Tour: Strange P. 5 J. Hoberman AFTERIMAGE P. 17 BAMPFA Closed 11/SAT 4:30 Five Dedicated to Ozu Lands of Promise and Peril: 11:30, 1:00 Great Cosmic Eyes Introduction by Donna Geographies of California opens P. 11 26/THU GALLERY + STUDIO P. 7 Honarpisheh KIAROSTAMI P. 16 12:00 Fanny and Alexander P. 21 1:30 The Tiger of Eschnapur P. 25 7:00 Amazing Grace P. 14 12/THU 7:00 Varda by Agnès VARDA P. 22 3:00 Guts ROUNDTABLE READING P. 7 7:00 River’s Edge 2/MON Introduction by J. Hoberman 3:45 The Indian Tomb P. 25 27/FRI 6:30 Art, Health, and Equity in the City AFTERIMAGE P. 17 6:00 Cléo from 5 to 7 VARDA P. 23 2:00 Tokyo Twilight P. 15 of Richmond ARTS + DESIGN P. 5 8:00 Eraserhead LYNCH P. 26 13/FRI 5:00 Amazing Grace P. -

Set Name Card Description Auto Mem #'D Base Set 1 Harold Sakata As Oddjob Base Set 2 Bert Kwouk As Mr

Set Name Card Description Auto Mem #'d Base Set 1 Harold Sakata as Oddjob Base Set 2 Bert Kwouk as Mr. Ling Base Set 3 Andreas Wisniewski as Necros Base Set 4 Carmen Du Sautoy as Saida Base Set 5 John Rhys-Davies as General Leonid Pushkin Base Set 6 Andy Bradford as Agent 009 Base Set 7 Benicio Del Toro as Dario Base Set 8 Art Malik as Kamran Shah Base Set 9 Lola Larson as Bambi Base Set 10 Anthony Dawson as Professor Dent Base Set 11 Carole Ashby as Whistling Girl Base Set 12 Ricky Jay as Henry Gupta Base Set 13 Emily Bolton as Manuela Base Set 14 Rick Yune as Zao Base Set 15 John Terry as Felix Leiter Base Set 16 Joie Vejjajiva as Cha Base Set 17 Michael Madsen as Damian Falco Base Set 18 Colin Salmon as Charles Robinson Base Set 19 Teru Shimada as Mr. Osato Base Set 20 Pedro Armendariz as Ali Kerim Bey Base Set 21 Putter Smith as Mr. Kidd Base Set 22 Clifford Price as Bullion Base Set 23 Kristina Wayborn as Magda Base Set 24 Marne Maitland as Lazar Base Set 25 Andrew Scott as Max Denbigh Base Set 26 Charles Dance as Claus Base Set 27 Glenn Foster as Craig Mitchell Base Set 28 Julius Harris as Tee Hee Base Set 29 Marc Lawrence as Rodney Base Set 30 Geoffrey Holder as Baron Samedi Base Set 31 Lisa Guiraut as Gypsy Dancer Base Set 32 Alejandro Bracho as Perez Base Set 33 John Kitzmiller as Quarrel Base Set 34 Marguerite Lewars as Annabele Chung Base Set 35 Herve Villechaize as Nick Nack Base Set 36 Lois Chiles as Dr. -

Pdf Ennio Flaiano Y Rafael Azcona: Historia De Un Universo Compartido / Giovanna Zanella Leer Obra

Università degli Studi di Udine Ennio Flaiano y Rafael Azcona Historia de un universo compartido Giovanna Zanella Memoria de Licenciatura Facultad: Lengua y Literatura extranjera Directora: Dott. Renata Londero 2000-2001 UNIVERSITÀ DEGLI STUDI DI UDINE FACOLTÀ DI LINGUE E LETTERATURE STRANIERE Corso di Laurea in Lingue e Letterature Straniere Tesi di Laurea ENNIO FLAIANO Y RAFAEL AZCONA HISTORIA DE UN UNIVERSO COMPARTIDO Relatore: Laureanda: Dott. Renata Londero Giovanna Zanella ANNO ACCADEMICO 2000-2001 AGRADECIMIENTOS Durante la realización del presente trabajo he estado principalmente en la Universidad de Alicante, donde he podido contar en todo momento con la valiosa colaboración y los imprescindibles consejos de Juan Antonio Ríos, y con la disponibilidad de la Biblioteca Virtual Miguel de Cervantes, que precisamente este año ha abierto un portal de autor dedicado a Rafael Azcona (consultable en cervantesvirtual.com), cuyo material ha sido fundamental para mi estudio. Asimismo, por lo que concierne el material sobre Ennio Flaiano, he utilizado las numerosas publicaciones de la “Associazione Culturale Ennio Flaiano” de Pescara, cuyos volúmenes siempre han sido el apoyo más valioso en toda investigación sobre la figura y la obra del italiano. Por lo que respecta a la difícil labor de conseguir películas de los años 50, 60 y 70, tengo que agradecer a Cristina Ros de la Universidad de Alicante por haberme ofrecido la oportunidad de ver El Anacoreta, de Juan Esterlich; a la “Cineteca del Friuli”, que me ha facilitado la visión de La cagna de Marco Ferreri; al “Laboratorio Cinema e Multimedia” de la Universidad de Udine y a la “Filmoteca del Museo” de la Universidad de Alicante. -

US Trade Deficit

European Union1 Change in 2006 from 2005: U.S. trade deficit: Decreased by $6.8 billion (5 percent) to $132.8 billion U.S. exports: Increased by $29.1 billion (17 percent) to $196.5 billion U.S. imports: Increased by $22.3 billion (7 percent) to $329.3 billion The European Union (EU) and the United States have the world’s largest bilateral trade relationship.2 The EU was the largest U.S. trading partner in terms of total trade and the largest source of U.S. imports, and second only to Canada as a destination for U.S. exports in 2006. Germany, the United Kingdom, and France accounted for 52 percent of U.S. exports to the EU and 54 percent of U.S. imports from the EU. The U.S. trade deficit with the EU decreased by 5 percent to $132.8 billion in 2006, after reaching a five-year high in 2005. The U.S. trade deficit with the EU is the second-largest after the deficit with China. U.S. Exports The largest absolute increases in U.S. exports to the EU in 2006 were in the transportation equipment, chemicals and related products, and minerals and metals sectors (table EU-1). U.S. exports of motor vehicles to the EU increased by $4.3 billion in 2006 (table EU-2). Such exports to Germany alone amounted to $3.1 billion. Sales of passenger vehicles in Germany were strong because customers brought forward purchases that may have otherwise been made in 2007 to avoid a 3 percentage point increase in the VAT rate introduced in January 2007.3 Precious metals and non-numismatic coin shipments from the United States to the EU increased by $3.4 billion (154 percent) to $5.6 billion in 2006. -

El Cine Barraneche

1 EL CINE EL CINE ______________________________________________________________________________ JUAN JOSÉ BARRENECHE CRITICO CINEMATOGRÁFICO E D I T 0 R I A L B R U G U E R A , S . A . BARCELONA * BOGOTÁ * BUENOS AIRES * CARACAS * MÉXICO Copyright de la presente edicion: © J. J. Barreneche - 1971 sobre el texto literario © Archivo gráfico Bruguera, S.A. 1971 sobre la cubierta. La presente edición es propiedad de EDITORIAL BRUGUERA, S. A. Mora la Nueva, 2. Barcelona {España) lª. Edición: noviembre, 1971 Printed in Spain Impreso un España Depósito Legal B 30.578 - 1971 Impreso en los Talleres Gráficos de EDITORIAL BRUGUERA. S. A. Mora la Nueva, 2 · Barcelona - 1971 NOTA DEL EDITOR La radio primero, y últimamente la televisión, han popularizado una serie de programas cuyo principal atractivo radica en poner a prueba los conocimientos que sobre determinada materia posee el concursante. ¿Cree usted que, sometido a una prueba análoga, por ejemplo, sobre el tema objeto de esta obra, saldría airoso de ella? Probablemente usted posee una amplia serie de conocimientos diversos, producto de sus estudios, de sus lecturas, de su experiencia o su interés por determinada materia. Estos conocimientos le permiten, en ocasiones, dar prueba de su cultura, ante sus amistades, en familia o en su vida profesional, pero no es lo mismo brillar en una conversación que enfrentarse con un examen concebido para poner a prueba, no solo su preparación, sino también su retentiva. Esta colección esta pensada para que usted mismo pueda autocalificarse sobre sus conocimientos de diversas materias, comprobar el grado “real” de su dominio del tema y permitirle, una vez comprobados aquellos aspectos en que sus respuestas fueron más vacilantes, subsanar esta deficiencia proporcionalmente los datos necesarios para ello. -

Bamcinématek Presents Strange Victories: Black Soldiers and World War II, a Series Focused on African-Americans’ Experiences During the War, Nov 10–16

BAMcinématek presents Strange Victories: Black Soldiers and World War II, a series focused on African-Americans’ experiences during the war, Nov 10–16 The Wall Street Journal is the title sponsor for BAMcinématek and BAM Rose Cinemas. October 10, 2017/Brooklyn, NY—From Friday, November 10 through Thursday, November 16, BAMcinématek presents Strange Victories: Black Soldiers and World War II. Inspired by the release of Dee Rees’ extraordinary new epic Mudbound (sneak peek screening at BAMcinématek Oct 24 with director Dee Rees in attendance), BAMcinématek presents a cross section of films that explore the unique experiences of black soldiers who, in racially-segregated units, fought the spread of fascism overseas only to face racism again on home soil. These groundbreaking classics, compelling documentaries, and revisionist action spectacles shine much-needed light on the experience of black soldiers and veterans as the United States continues to struggle today with its legacy of historical, systemic racism. The series begins with Spike Lee’s Miracle at St. Anna (2008—Nov 10), a necessary corrective that mobilizes familiar tropes of the traditional Hollywood World War II movie to present a powerful story of black infantrymen who fought for a country that saw them as second-class citizens. On a similarly thrilling scale is Anthony Hemingway’s Red Tails (2012—Nov 12) about the Tuskegee Airmen, a legendary African-American fighter pilot unit. Its all-star cast features David Oyelowo, Michael B. Jordan, and Cuba Gooding, Jr. Mark Robson’s Home of the Brave (1949—Nov 14) was among the first studio-era dramas to address the challenges faced by black soldiers, including PTSD, bigotry, and the embedded racism of everyday life. -

Cahiers-42-43-Le-Moyen-Age-Au-Cin--Ma-.Pdf

Nourri de la matière d’une mémorable Telles apparaissaient, au sentiment de CONFRONTATION, ce numéro notre équipe, les conditions de Editorial double participe très évidemment de l’équilibre matériel et rédactionnel la tradition historienne de notre revue. d’une publication parvenue à maturité. De plus, cette livraison nous autorise Telles demeurent aujourd’hui les à considérer comme gagnés, dans perspectives de son développement, l’immédiat, deux paris plus récents : alors même que Marcel Oms a décidé soutenir un rythme de parution de quitter la direction de ces CAHIERS régulier et mettre en harmonie la vie auxquels il avait donné la forme et la propre de la revue et l’ensemble des vie, et qu’il continue, naturellement, à activités de l’Institut Jean Vigo. inspirer. Pierre GUIBBERT LES CAHIERS SOMMAIRE De la CINEMATHEQUE Revue d’histoire du Cinéma ! DES IMAGES POUR L’ENFANCE. 6. Michel ZINK : Projection dans l’enfance, projection de l’enfance : le Fondateur : Marcel OMS Moyen Age au cinéma 9. Pierre GUIBBERT : ‘’Pour les petits et pour les grands’’ 21 François de la BRETEQUE : ‘’Une figure obligée’’ du film de chevalerie : Directeur : Pierre GUIBBERT le tournoi Administrateur : Pierre ROURA Rédaction : André ABBET ! AU ‘’TEMPS DES CATHEDRALES’" 29. Jean François SIX : François d’Assise Barthélémy AMENGUAL 35. Vittorio MARTINELLI : Filmographie de Francesco d’Assisi José BALDIZZONE François de la BRETEQUE JEANNE D’ARC Raymond CHIRAT 37. Claude LAFAYE : Jeanne Fugitive 39. Régine PERNOUD : Jeanne d’Arc à l’écran Jean A.MITRY 42. Marcel Oms : De Lavisse à Michelet ou Jeanne d’arc entre deux Ricardo MUNOZ-SUAY Guerres.. -

1 Praxinoscope-Théâtre D'emile Reynaud. Dans Sa Boite En Bois

Praxinoscope-Théâtre d'Emile Reynaud. Dans sa boite en bois avec 5 décors dont un en métal, 29 vues, 1 porte abat-jour, abat-jour, porte bougie. 500 / 600 On y joint des photos sur cet objet et Emile Reynaud. BELL & HOWELL "TQ III Specialist" Projecteur 16 mm fonctionnant à 18, soit à 24 images/seconde. 2 150 / 200 Courant continu. Obturateur à 2 pales. Objectif 1:1,2/55 mm (diamètre 52 mm). Griffe à 3 dents . Bobine jusquà 35 cm. (Prise électrique coupée) PAILLARD "G 3" Projecteur 16 mm, alimenté par un moteur en 110 volts. Cadence 3 16 i/s variable. Objectif Meyer Görlitz Kinon Superior 1 : 120 / 150 1,6/50mm. Bobines jusqu'à 120m. Dans sa boite d'origine avec notice de fonctionnement, ampoule mazda, quatre b obines et un objectif. Ensemble de 110 films amateurs Pathé Baby des années 30. Ces films sont sur des voyages (Mont Saint-Michel), fête de 4 famille, etc.. 150 / 200 On y joint une bande avec quatre films amateurs de 1925 sur Paris. MECCANO TRI-ANG "Minicinex Walt Disney" Projecteur de Cinéma 8m/m à piles. Dans sa boite d'origine avec ces notices. 5 50 / 60 Trois films inclus et trois autres joints. On y joint un projecteur "Minema" sans boite avec 31 bandes numérotées 113 à 143? WALT DISNEY Ensemble de sept films Super 8 complet en boite dont : - Le Premier amour de Bambi - Le Pimpant Dalmatien - Donald fait son beurre - La Toilette de Grincheux 6 50 / 60 - Concert à la Ferme - Donald aux sports d'Hiver - Le Clown du cirque (manque base de la boite) On y joint deux brochures de Film Office de 1978 presentant le catalogue et les tarifs de film super 8 dont une juste sur Walt Disney. -

Di Hollywood Party

“NARNI. LE VIE DEL CINEMA” RASSEGNA DI CINEMA RESTAURATO 21a EDIZIONE . DAL 7 al 12 LUGLIO 2015 A NARNI (TR) . INGRESSO GRATUITO - LA 21a RASSEGNA DI CINEMA CLASSICO RESTAURATO È DEDICATA ALLE DUE GUERRE MONDIALI CON I FILM: GUARDIE E LADRI, UOMINI CONTRO, SENZA PIETÀ, UNA GIORNATA PARTICOLARE, SCHINDLER’S LIST, PORCO ROSSO - GLI OSPITI DI QUESTA EDIZIONE: EMILIO GENTILE, SIMONA COLARIZI, MARCELLO PEZZETTI, PIERO TERRACINA, ALESSANDRO BENCIVENNI, ALESSANDRO E FRANCESCO LATTUADA, OTTAVIA MONICELLI, LUCIANO TOVOLI, MAURIZIO PONZI, LA “BANDA” DI HOLLYWOOD PARTY - PER I PIÙ PICCOLI TORNA LA 3a EDIZIONE DEL CINEMA ANIMATO RESTAURATO. TUTTE LE SERE UN LABORATORIO CREATIVO E UN CORSO CON I DISEGNATORI DI “TOPOLINO”, ANDREA LUCCI E DAVIDE BALDONI - TUTTI I GIORNI: CIAK! AL RISTORANTE/IL CINEMA SI MANGIA ANCHE A CENA Dal 7 al 12 luglio 2015 Narni (TR) ospiterà la 21a edizione di “Le vie del cinema”, la Rassegna di cinema restaurato, diretta da Giuliano Montaldo e Alberto Crespi e organizzata per iniziativa del Comune di Narni con la collaborazione della Fondazione Centro Sperimentale di Cinematografia – Cineteca Nazionale. Tante le iniziative previste all’interno di questa ventunesima edizione di “Le vie del cinema”. TORNA LA 21a EDIZIONE DELLA RASSEGNA DI CINEMA RESTAURATO. Come ogni anno, anche questa edizione, sarà ricca di film di recente recupero proiettati ogni sera sotto le stelle, a partire dalle 21.30, sul grande schermo allestito nel Parco del Pini di Narni Scalo e presentati da ospiti illustri. Il filo rosso che lega le proposte di questa 21.ma edizione di Le vie del cinema, è quello della guerra e dei suoi effetti sulla società e sulla convivenza civile quando torna, o dovrebbe tornare, la pace. -

War Cinema– Or How British Films Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Affluent Society

1 THE PROFESSIONAL OFFICER CLASS IN POST- WAR CINEMA– OR HOW BRITISH FILMS LEARNED TO STOP WORRYING AND LOVE THE AFFLUENT SOCIETY A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Andrew Roberts College of Business, Arts and Social Sciences of Brunel University 22nd September2014 2 ABSTRACT My central argument is that mainstream British cinema of the 1951 – 1965 period marked the end of the paternalism, as exemplified by a professional ‘officer class’, as consumerism gradually came to be perceived as the norm as opposed to a post-war enemy. The starting point is 1951, the year of the Conservative victory in the General Election and a time which most films were still locally funded. The closing point is 1965, by which point the vast majority of British films were funded by the USA and often featured a youthful and proudly affluent hero. Thus, this fourteen year describes how British cinema moved away from the People as Hero guided by middle class professionals in the face of consumerism. Over the course of this work, I will analyse the creation of the archetypes of post-war films and detail how the impact of consumerism and increased Hollywood involvement in the UK film industry affected their personae. However, parallel with this apparently linear process were those films that questioned or attacked the wartime consensus model. As memories of the war receded, and the Rank/ABPC studio model collapsed, there was an increasing sense of deracination across a variety of popular British cinematic genres. From the beginning of our period there is a number films that infer that the “Myth of the Blitz”, as developed in a cinematic sense, was just that and our period ends with films that convey a sense of a fragmenting society. -

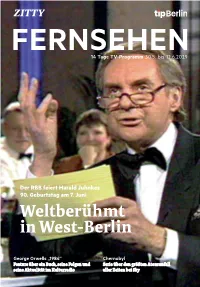

Weltberühmt in West-Berlin

FERNSEHEN 14 Tage TV-Programm 30.5. bis 12.6.2019 Der RBB feiert Harald Juhnkes 90. Geburtstag am 7. Juni Weltberühmt in West-Berlin George Orwells „1984“ Chernobyl Feature über ein Buch, seine Folgen und Serie über den größten Atomunfall seine Aktualität im Kulturradio aller Zeiten bei Sky tip_TV_1219_01_Titel.indd 1 16.05.19 17:39 Fernsehen 30.5. – 12.6. Wahlkrampf KOMMENTAR VOM TELEVISOR Nach Europa, das weiß man ja nach einem Blick ins Europäische Parlament, schicken die Parteien nicht ihre besten Leute. Mit Schrecken denke ich an das Teletubby-Video der Grünen-Abgeordne- ten Jan Philipp Albrecht, Franziska Keller und Terry Reintke: „Juhu!“ Und das ist nach der letzten Wahl entstanden. Aber auch vor der Wahl bekleckert sich keine Partei mit Ruhm, wenn es um die Juhnkes Definition von Glück: „Keine Termine und leicht einen sitzen.“ kleinen Clips im Fernsehen geht. Die AfD etwa hat ja bekanntlich gar keinen Bock auf Europa und will die EU am liebsten Der letzte Entertainer abschaffen. Warum zumGeier soll ich dann eigentlich 99 Sekunden meines Harald Juhnke zum 90. Geburtstag Lebens damit vergeigen, mir das Europa- wahlprogramm der Nazi- Schlümpfe Der berühmteste Dialog in dem Marlon- Verlierer der Berliner Geschichte, den anzugucken? Die Grünen klauen mal Brando-Film „Der Wilde“ geht so: „Woge- „Hauptmann von Köpenick“. eben dreist das Konzept der Musiker- gen rebelliert ihr eigentlich?“, wird Brando Ausfälle, Körperverletzung und Be- seite Playing For Change, indem sie ver- gefragt. „Was haben Sie denn so?“, lautet leidigung, stets schafft Juhnke ein Come- schiedene Musikerinnen in unterschiedli- die Antwort. Wer das sagt, das ist Harald back. -

Slovenia's Finest Films Showing at the Cleveland Cinematheque, Sundays in August

Visit www.clevelandslovenian.com US Embassy Ljubljana www.youtube.com/user/USEmbassyLjubljana Joined: June 19, 2008 This is the official Channel of the Embassy of the United States in Ljubljana, Slovenia. www.slovenia.usembassy.gov The U.S. Embassy in Ljubljana conducts diplomatic relations with the Republic of Slovenia. Bilateral cooperation between the U.S. and Slovenia includes political, economic, commercial, defense and security, educational, and exchange activities. The Embassy also provides consular services, issuing visas for visitors to the United States and assisting U.S. citizens in Slovenia with passports and other issues. At the head of the U.S. diplomatic mission in Slovenia are the Chief of Mission, Ambassador Yousif Ghafari, and the Deputy Chief of Mission, Maryruth Coleman. *** Sporočilo za javnost Generalni konzulat RS v Clevelandu sporoča, da bodo volitve v državni zbor Republike Slovenije v nedeljo, 21. septembra 2008, od 9. do 17. ure. V Clevelandu bodo volitve potekale tako kot lani v Slovenskem domu za upokojence – SLOVENE HOME FOR THE AGED, 18621 Neff Road, Cleveland, OH 44119. S seboj prinesite osebni dokument z vašo fotografijo, na podlagi katerega bo mogoče ugotoviti vašo istovetnost (potni list, vozniško dovoljenje, osebna izkaznica...). Za dodatne informacije lahko odprete spletno stran www.dvk.gov.si, lahko pa se obrnete tudi na Generalni konzulat RS v Clevelandu na tel. št. 216-589 9220. Slovenia's Finest Films Showing at the Cleveland Cinematheque, Sundays in August Joe Valenčič Enjoy the rare opportunity to view classic films from Slovenia throughout August. The film series "Six Decades of Slovenian Cinema" is the first time many of the country's most important films will be shown in the city with more Slovenians outside of Europe.