Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Black Soldiers in Liberal Hollywood

Katherine Kinney Cold Wars: Black Soldiers in Liberal Hollywood n 1982 Louis Gossett, Jr was awarded the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor for his portrayal of Gunnery Sergeant Foley in An Officer and a Gentleman, becoming theI first African American actor to win an Oscar since Sidney Poitier. In 1989, Denzel Washington became the second to win, again in a supporting role, for Glory. It is perhaps more than coincidental that both award winning roles were soldiers. At once assimilationist and militant, the black soldier apparently escapes the Hollywood history Donald Bogle has named, “Coons, Toms, Bucks, and Mammies” or the more recent litany of cops and criminals. From the liberal consensus of WWII, to the ideological ruptures of Vietnam, and the reconstruction of the image of the military in the Reagan-Bush era, the black soldier has assumed an increasingly prominent role, ironically maintaining Hollywood’s liberal credentials and its preeminence in producing a national mythos. This largely static evolution can be traced from landmark films of WWII and post-War liberal Hollywood: Bataan (1943) and Home of the Brave (1949), through the career of actor James Edwards in the 1950’s, and to the more politically contested Vietnam War films of the 1980’s. Since WWII, the black soldier has held a crucial, but little noted, position in the battles over Hollywood representations of African American men.1 The soldier’s role is conspicuous in the way it places African American men explicitly within a nationalist and a nationaliz- ing context: U.S. history and Hollywood’s narrative of assimilation, the combat film. -

Film Screenings at the Old Fire Station, 84 Mayton Street, N7 6QT

iU3A Classic Film Group 2017-18 Winter Programme: January-March 2018: "Classic Curios" All film screenings at The Old Fire Station, 84 Mayton Street, N7 6QT Plot Summaries and Reviews courtesy of The Internet Movie Database Date/Time: Tuesday, 9th January 10.30 and 14.00; Wednesday, 10th January 13.30 Title: The Night of The Hunter (USA, 1955, 89 minutes, English HOH Subtitles) Director and Cast: Charles Laughton; Robert Mitcham, Shelley Winters, Lillian Gish Plot Summary: A religious fanatic marries a gullible widow whose young children are reluctant to tell him where their real father hid $10,000 that he'd stolen in a robbery. Reviews: "Part fairy tale and part bogeyman thriller -- a juicy allegory of evil, greed and innocence, told with an eerie visual poetry."(San Francisco Chronicle) "It’s the most haunted and dreamlike of all American films, a gothic backwoods ramble with the Devil at its heels." (Time out London) "An enduring masterpiece - dark, deep, beautiful, aglow."(Chicago Reader) Date: Tuesday, 23rd January 10.30 and 14.00; No Wednesday, 24th Jan screening Title: La Muerte de Un Burócrata /Death of A Bureaucrat (Cuba, 1966, 85 minutes, Spanish with English Subtitles) Director and Cast: Tomás Gutiérrez Alea; Salvador Wood, Silvia Planas, Manuel Estanillo Plot Summary: A young man attempts to fight the system in an entertaining account of the tyranny of red tape and of bureaucracy run amok. Reviews: "A mucho funny black comedy about the horrors of institutionalized red tape. It plays as an homage to silent screen comics such as Buster Keaton and Harold Lloyd, the more recent ones such as Laurel and Hardy, and all those who, in one way or another, have taken part in the film industry since the days of Lumiére." (Ozu's World Moview Reviews) "Gutiérrez Alea's pitch-black satire is witty, sarcastic and eternally relevant." (filmreporter.de) Date: Tuesday, 6th February 10.30 and 14.00; Wednesday, 7th February 13.30 Title: Leave Her To Heaven (USA, 1945, 105 minutes, English HOH subtitles) Director and Cast: John M. -

Berkeley Art Museum·Pacific Film Archive W in Ter 20 19

WINTER 2019–20 WINTER BERKELEY ART MUSEUM · PACIFIC FILM ARCHIVE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PROGRAM GUIDE ROSIE LEE TOMPKINS RON NAGLE EDIE FAKE TAISO YOSHITOSHI GEOGRAPHIES OF CALIFORNIA AGNÈS VARDA FEDERICO FELLINI DAVID LYNCH ABBAS KIAROSTAMI J. HOBERMAN ROMANIAN CINEMA DOCUMENTARY VOICES OUT OF THE VAULT 1 / 2 / 3 / 4 / 5 / 6 CALENDAR DEC 11/WED 22/SUN 10/FRI 7:00 Full: Strange Connections P. 4 1:00 Christ Stopped at Eboli P. 21 6:30 Blue Velvet LYNCH P. 26 1/SUN 7:00 The King of Comedy 7:00 Full: Howl & Beat P. 4 Introduction & book signing by 25/WED 2:00 Guided Tour: Strange P. 5 J. Hoberman AFTERIMAGE P. 17 BAMPFA Closed 11/SAT 4:30 Five Dedicated to Ozu Lands of Promise and Peril: 11:30, 1:00 Great Cosmic Eyes Introduction by Donna Geographies of California opens P. 11 26/THU GALLERY + STUDIO P. 7 Honarpisheh KIAROSTAMI P. 16 12:00 Fanny and Alexander P. 21 1:30 The Tiger of Eschnapur P. 25 7:00 Amazing Grace P. 14 12/THU 7:00 Varda by Agnès VARDA P. 22 3:00 Guts ROUNDTABLE READING P. 7 7:00 River’s Edge 2/MON Introduction by J. Hoberman 3:45 The Indian Tomb P. 25 27/FRI 6:30 Art, Health, and Equity in the City AFTERIMAGE P. 17 6:00 Cléo from 5 to 7 VARDA P. 23 2:00 Tokyo Twilight P. 15 of Richmond ARTS + DESIGN P. 5 8:00 Eraserhead LYNCH P. 26 13/FRI 5:00 Amazing Grace P. -

The Inventory of the Richard Roud Collection #1117

The Inventory of the Richard Roud Collection #1117 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center ROOD, RICHARD #1117 September 1989 - June 1997 Biography: Richard Roud ( 1929-1989), as director of both the New York and London Film Festivals, was responsible for both discovering and introducing to a wider audience many of the important directors of the latter half th of the 20 - century (many of whom he knew personally) including Bernardo Bertolucci, Robert Bresson, Luis Buiiuel, R.W. Fassbinder, Jean-Luc Godard, Werner Herzog, Terry Malick, Ermanno Ohni, Jacques Rivette and Martin Scorsese. He was an author of books on Jean-Marie Straub, Jean-Luc Godard, Max Ophuls, and Henri Langlois, as well as the editor of CINEMA: A CRITICAL DICTIONARY. In addition, Mr. Roud wrote extensive criticism on film, the theater and other visual arts for The Manchester Guardian and Sight and Sound and was an occasional contributor to many other publications. At his death he was working on an authorized biography of Fran9ois Truffaut and a book on New Wave film. Richard Roud was a Fulbright recipient and a Chevalier in the Legion of Honor. Scope and contents: The Roud Collection (9 Paige boxes, 2 Manuscript boxes and 3 Packages) consists primarily of book research, articles by RR and printed matter related to the New York Film Festival and prominent directors. Material on Jean-Luc Godard, Francois Truffaut and Henri Langlois is particularly extensive. Though considerably smaller, the Correspondence file contains personal letters from many important directors (see List ofNotable Correspondents). The Photographs file contains an eclectic group of movie stills. -

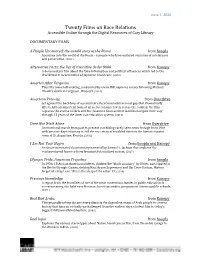

Twenty Films on Race Relations Accessible Online Through the Digital Resources of Cary Library

June 1, 2020 Twenty Films on Race Relations Accessible Online through the Digital Resources of Cary Library DOCUMENTARY FILMS A People Uncounted: the untold story of the Roma from hoopla A journey into the world of the Roma - a people who have endured centuries of intolerance and persecution. (2014) Alternative Facts: the lies of Executive Order 9066 from Kanopy A documentary film about the false information and political influences which led to the World War II incarceration of Japanese Americans. (2018) America After Ferguson from Kanopy This PBS town hall meeting, moderated by Gwen Ifill, explores events following Michael Brown's death in Ferguson, Missouri. (2014) American Promise from Overdrive Set against the backdrop of a persistent educational achievement gap that dramatically affects African-American boys at all socioeconomic levels across the country, the film captures the stories of Idris and his classmate Seun as their families navigate their way through 13 years of the American education system. (2013) Dare Not Walk Alone from Overdrive An emotional march from past to present combining rarely seen news footage from 1964 with present-day testimony to tell the true story of troubled times in the historic tourist town of St. Augustine, Florida. (2006) I Am Not Your Negro from hoopla and Kanopy An Oscar-nominated documentary narrated by Samuel L. Jackson that explores the continued peril America faces from institutionalized racism. (2017) Olympic Pride, American Prejudice from hoopla In 1936, 18 African American athletes, dubbed the "black auxiliary" by Hitler, participated in the Berlin Olympic Games, defying Nazi Aryan Supremacy and Jim Crow Racism. -

Set Name Card Description Auto Mem #'D Base Set 1 Harold Sakata As Oddjob Base Set 2 Bert Kwouk As Mr

Set Name Card Description Auto Mem #'d Base Set 1 Harold Sakata as Oddjob Base Set 2 Bert Kwouk as Mr. Ling Base Set 3 Andreas Wisniewski as Necros Base Set 4 Carmen Du Sautoy as Saida Base Set 5 John Rhys-Davies as General Leonid Pushkin Base Set 6 Andy Bradford as Agent 009 Base Set 7 Benicio Del Toro as Dario Base Set 8 Art Malik as Kamran Shah Base Set 9 Lola Larson as Bambi Base Set 10 Anthony Dawson as Professor Dent Base Set 11 Carole Ashby as Whistling Girl Base Set 12 Ricky Jay as Henry Gupta Base Set 13 Emily Bolton as Manuela Base Set 14 Rick Yune as Zao Base Set 15 John Terry as Felix Leiter Base Set 16 Joie Vejjajiva as Cha Base Set 17 Michael Madsen as Damian Falco Base Set 18 Colin Salmon as Charles Robinson Base Set 19 Teru Shimada as Mr. Osato Base Set 20 Pedro Armendariz as Ali Kerim Bey Base Set 21 Putter Smith as Mr. Kidd Base Set 22 Clifford Price as Bullion Base Set 23 Kristina Wayborn as Magda Base Set 24 Marne Maitland as Lazar Base Set 25 Andrew Scott as Max Denbigh Base Set 26 Charles Dance as Claus Base Set 27 Glenn Foster as Craig Mitchell Base Set 28 Julius Harris as Tee Hee Base Set 29 Marc Lawrence as Rodney Base Set 30 Geoffrey Holder as Baron Samedi Base Set 31 Lisa Guiraut as Gypsy Dancer Base Set 32 Alejandro Bracho as Perez Base Set 33 John Kitzmiller as Quarrel Base Set 34 Marguerite Lewars as Annabele Chung Base Set 35 Herve Villechaize as Nick Nack Base Set 36 Lois Chiles as Dr. -

Mario Van Peebles's <I>Panther</I>

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Papers in Communication Studies Communication Studies, Department of 8-2007 Mario Van Peebles’s Panther and Popular Memories of the Black Panther Party Kristen Hoerl Auburn University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/commstudiespapers Part of the Critical and Cultural Studies Commons, Gender, Race, Sexuality, and Ethnicity in Communication Commons, and the Other Communication Commons Hoerl, Kristen, "Mario Van Peebles’s Panther and Popular Memories of the Black Panther Party" (2007). Papers in Communication Studies. 196. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/commstudiespapers/196 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Communication Studies, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Papers in Communication Studies by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Published in Critical Studies in Media Communication 24:3 (August 2007), pp. 206–227; doi: 10.1080/07393180701520900 Copyright © 2007 National Communication Association; published by Routledge/Taylor & Francis. Used by permission. Published online August 15, 2007. Mario Van Peebles’s Panther and Popular Memories of the Black Panther Party Kristen Hoerl Department of Communication and Journalism, Auburn University, Auburn, Alabama, USA Corresponding author – Kristen Hoerl, email [email protected] Abstract The 1995 movie Panther depicted the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense as a vibrant but ultimately doomed social movement for racial and economic justice during the late 1960s. Panther’s narrative indicted the white-operated police for perpetuating violence against African Americans and for un- dermining movements for black empowerment. -

Nixon Reacts to UN Vote It

Whoops, there goes. Some base residents who failed to take action last week may find that late might as well be never. As part of the base-wide Shape Up, Gitmo! campaign now under way, many of the base's derelict cars were tagged last week with noti- ces that they would towed to the dump if owners did not remove them prior to Oct. 25. Citing SOPA Instruction 5400.2, Chapter 2, the notice said it contrary to regulations to repair vehicles outside of the Hobby Owners should remember that improperly parked vehicles may be confused Shop Garage on Marti Rd. with abandoned ones, as could be the case above. M& NAVAL CUATAM4AgSr. Y, CUBA Bias it Canadians Protest Atomic Test WASHINGTON (AP) -- The Nixon administration announced yesterday plans t o proceed with a huge underground a- tomic blast in th e Aleutian Islands, drawing expres- sions of dismay from the Canadian ambassador here. Although Sen. .1 ike Gravel, D-Alaska, told newsmen the blast, testing a 5-megaton anti-missile warhead, is THURSDAY. OCTOBER 28, 1971 scheduled for Nov . 4, James R. Schlesinger, chariman of the Atomic Energy Commission, told newsmen a test date has not been established. Schlesinger said, however, that preparations would be completed within a week. Meanwhile, seven environmental Nixon Reacts to U.N. Vote groups, headed by the Committe for WASHINGTON (AP)--President Nixon, giving a delayed reaction to Monday Nuclear Responsibility, are seeking night's events that saw the United Nations admit mainland China and expel to halt the test through court ac- Taiwan, suggested yesterday the result could be lessened U.S. -

The Wooster Voice (Wooster, OH), 1951-10-19

The College of Wooster Open Works The oV ice: 1951-1960 "The oV ice" Student Newspaper Collection 10-19-1951 The oW oster Voice (Wooster, OH), 1951-10-19 Wooster Voice Editors Follow this and additional works at: https://openworks.wooster.edu/voice1951-1960 Recommended Citation Editors, Wooster Voice, "The oosW ter Voice (Wooster, OH), 1951-10-19" (1951). The Voice: 1951-1960. 15. https://openworks.wooster.edu/voice1951-1960/15 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the "The oV ice" Student Newspaper Collection at Open Works, a service of The oC llege of Wooster Libraries. It has been accepted for inclusion in The oV ice: 1951-1960 by an authorized administrator of Open Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Hoot Mon! Fish Fry Saturday Published By the Students of the College of Woosler LXVI Volume WOOSTER, OHIO, FRIDAY, OCTOBER 19. 1951 Number 5 Compton Pinch Hits flj a 2 For Oppenheimer booster m a u w u u M In Symposium National attention will be fo- 1 Gala Weekend Features cused on Wooster next week end when a five-ma- n symposium on Royalty, "Twentieth Century Concepts of Varied Program Homecoming festivities on Man" will be held in Memorial the Wooster campus will gather momentum tonight and tomorrow as Chapel. hundreds of alumni and visitors return for a weekend packed with special events in their honor. Many departments and organizations, including Robert Oppenheimer has been the sections and local clubs, Dr. J. have planned a variety of entertainment features to welcome the forced to cancel his engagement to crowd. -

Raoul Walsh to Attend Opening of Retrospective Tribute at Museum

The Museum of Modern Art jl west 53 Street, New York, N.Y. 10019 Tel. 956-6100 Cable: Modernart NO. 34 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE RAOUL WALSH TO ATTEND OPENING OF RETROSPECTIVE TRIBUTE AT MUSEUM Raoul Walsh, 87-year-old film director whose career in motion pictures spanned more than five decades, will come to New York for the opening of a three-month retrospective of his films beginning Thursday, April 18, at The Museum of Modern Art. In a rare public appearance Mr. Walsh will attend the 8 pm screening of "Gentleman Jim," his 1942 film in which Errol Flynn portrays the boxing champion James J. Corbett. One of the giants of American filmdom, Walsh has worked in all genres — Westerns, gangster films, war pictures, adventure films, musicals — and with many of Hollywood's greatest stars — Victor McLaglen, Gloria Swanson, Douglas Fair banks, Mae West, James Cagney, Humphrey Bogart, Marlene Dietrich and Edward G. Robinson, to name just a few. It is ultimately as a director of action pictures that Walsh is best known and a growing body of critical opinion places him in the front rank with directors like Ford, Hawks, Curtiz and Wellman. Richard Schickel has called him "one of the best action directors...we've ever had" and British film critic Julian Fox has written: "Raoul Walsh, more than any other legendary figure from Hollywood's golden past, has truly lived up to the early cinema's reputation for 'action all the way'...." Walsh's penchant for action is not surprising considering he began his career more than 60 years ago as a stunt-rider in early "westerns" filmed in the New Jersey hills. -

Violence and Masculinity in Hollywood War Films During World War II a Thesis Submitted To

Violence and Masculinity in Hollywood War Films During World War II A thesis submitted to: Lakehead University Faculty of Arts and Sciences Department of History In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree in Master of Arts Matthew Sitter Thunder Bay, Ontario July 2012 Library and Archives Bibliothèque et Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de l'édition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-84504-2 Our file Notre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-84504-2 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant à la Bibliothèque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par télécommunication ou par l'Internet, prêter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des thèses partout dans le loan, distrbute and sell theses monde, à des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non- support microforme, papier, électronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriété du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette thèse. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la thèse ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent être imprimés ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

Ronald Davis Oral History Collection on the Performing Arts

Oral History Collection on the Performing Arts in America Southern Methodist University The Southern Methodist University Oral History Program was begun in 1972 and is part of the University’s DeGolyer Institute for American Studies. The goal is to gather primary source material for future writers and cultural historians on all branches of the performing arts- opera, ballet, the concert stage, theatre, films, radio, television, burlesque, vaudeville, popular music, jazz, the circus, and miscellaneous amateur and local productions. The Collection is particularly strong, however, in the areas of motion pictures and popular music and includes interviews with celebrated performers as well as a wide variety of behind-the-scenes personnel, several of whom are now deceased. Most interviews are biographical in nature although some are focused exclusively on a single topic of historical importance. The Program aims at balancing national developments with examples from local history. Interviews with members of the Dallas Little Theatre, therefore, serve to illustrate a nation-wide movement, while film exhibition across the country is exemplified by the Interstate Theater Circuit of Texas. The interviews have all been conducted by trained historians, who attempt to view artistic achievements against a broad social and cultural backdrop. Many of the persons interviewed, because of educational limitations or various extenuating circumstances, would never write down their experiences, and therefore valuable information on our nation’s cultural heritage would be lost if it were not for the S.M.U. Oral History Program. Interviewees are selected on the strength of (1) their contribution to the performing arts in America, (2) their unique position in a given art form, and (3) availability.