An Introduction to X-Ray Diffraction by Single Crystals and Powders

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Crystal Structures

Crystal Structures Academic Resource Center Crystallinity: Repeating or periodic array over large atomic distances. 3-D pattern in which each atom is bonded to its nearest neighbors Crystal structure: the manner in which atoms, ions, or molecules are spatially arranged. Unit cell: small repeating entity of the atomic structure. The basic building block of the crystal structure. It defines the entire crystal structure with the atom positions within. Lattice: 3D array of points coinciding with atom positions (center of spheres) Metallic Crystal Structures FCC (face centered cubic): Atoms are arranged at the corners and center of each cube face of the cell. FCC continued Close packed Plane: On each face of the cube Atoms are assumed to touch along face diagonals. 4 atoms in one unit cell. a 2R 2 BCC: Body Centered Cubic • Atoms are arranged at the corners of the cube with another atom at the cube center. BCC continued • Close Packed Plane cuts the unit cube in half diagonally • 2 atoms in one unit cell 4R a 3 Hexagonal Close Packed (HCP) • Cell of an HCP lattice is visualized as a top and bottom plane of 7 atoms, forming a regular hexagon around a central atom. In between these planes is a half- hexagon of 3 atoms. • There are two lattice parameters in HCP, a and c, representing the basal and height parameters Volume respectively. 6 atoms per unit cell Coordination number – the number of nearest neighbor atoms or ions surrounding an atom or ion. For FCC and HCP systems, the coordination number is 12. For BCC it’s 8. -

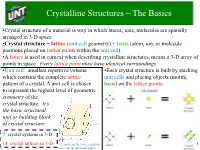

Crystal Structure of a Material Is Way in Which Atoms, Ions, Molecules Are Spatially Arranged in 3-D Space

Crystalline Structures – The Basics •Crystal structure of a material is way in which atoms, ions, molecules are spatially arranged in 3-D space. •Crystal structure = lattice (unit cell geometry) + basis (atom, ion, or molecule positions placed on lattice points within the unit cell). •A lattice is used in context when describing crystalline structures, means a 3-D array of points in space. Every lattice point must have identical surroundings. •Unit cell: smallest repetitive volume •Each crystal structure is built by stacking which contains the complete lattice unit cells and placing objects (motifs, pattern of a crystal. A unit cell is chosen basis) on the lattice points: to represent the highest level of geometric symmetry of the crystal structure. It’s the basic structural unit or building block of crystal structure. 7 crystal systems in 3-D 14 crystal lattices in 3-D a, b, and c are the lattice constants 1 a, b, g are the interaxial angles Metallic Crystal Structures (the simplest) •Recall, that a) coulombic attraction between delocalized valence electrons and positively charged cores is isotropic (non-directional), b) typically, only one element is present, so all atomic radii are the same, c) nearest neighbor distances tend to be small, and d) electron cloud shields cores from each other. •For these reasons, metallic bonding leads to close packed, dense crystal structures that maximize space filling and coordination number (number of nearest neighbors). •Most elemental metals crystallize in the FCC (face-centered cubic), BCC (body-centered cubic, or HCP (hexagonal close packed) structures: Room temperature crystal structure Crystal structure just before it melts 2 Recall: Simple Cubic (SC) Structure • Rare due to low packing density (only a-Po has this structure) • Close-packed directions are cube edges. -

C:\Documents and Settings\Alan Smithee\My Documents\MOTM

I`mt`qx1/00Lhmdq`knesgdLnmsg9Rbnkdbhsd This month’s mineral, scolecite, is an uncommon zeolite from India. Our write-up explains its origin as a secondary mineral in volcanic host rocks, the difficulty of collecting this fragile mineral, the unusual properties of the zeolite-group minerals, and why mineralogists recently revised the system of zeolite classification and nomenclature. OVERVIEW PHYSICAL PROPERTIES Chemistry: Ca(Al2Si3O10)A3H2O Hydrous Calcium Aluminum Silicate (Hydrous Calcium Aluminosilicate), usually containing some potassium and sodium. Class: Silicates Subclass: Tectosilicates Group: Zeolites Crystal System: Monoclinic Crystal Habits: Usually as radiating sprays or clusters of thin, acicular crystals or Hairlike fibers; crystals are often flattened with tetragonal cross sections, lengthwise striations, and slanted terminations; also massive and fibrous. Twinning common. Color: Usually colorless, white, gray; rarely brown, pink, or yellow. Luster: Vitreous to silky Transparency: Transparent to translucent Streak: White Cleavage: Perfect in one direction Fracture: Uneven, brittle Hardness: 5.0-5.5 Specific Gravity: 2.16-2.40 (average 2.25) Figure 1. Scolecite. Luminescence: Often fluoresces yellow or brown in ultraviolet light. Refractive Index: 1.507-1.521 Distinctive Features and Tests: Best field-identification marks are acicular crystal habit; vitreous-to-silky luster; very low density; and association with other zeolite-group minerals, especially the closely- related minerals natrolite [Na2(Al2Si3O10)A2H2O] and mesolite [Na2Ca2(Al6Si9O30)A8H2O]. Laboratory tests are often needed to distinguish scolecite from other zeolite minerals. Dana Classification Number: 77.1.5.5 NAME The name “scolecite,” pronounced SKO-leh-site, is derived from the German Skolezit, which comes from the Greek sklx, meaning “worm,” an allusion to the tendency of its acicular crystals to curl when heated and dehydrated. -

Types of Lattices

Types of Lattices Types of Lattices Lattices are either: 1. Primitive (or Simple): one lattice point per unit cell. 2. Non-primitive, (or Multiple) e.g. double, triple, etc.: more than one lattice point per unit cell. Double r2 cell r1 r2 Triple r1 cell r2 r1 Primitive cell N + e 4 Ne = number of lattice points on cell edges (shared by 4 cells) •When repeated by successive translations e =edge reproduce periodic pattern. •Multiple cells are usually selected to make obvious the higher symmetry (usually rotational symmetry) that is possessed by the 1 lattice, which may not be immediately evident from primitive cell. Lattice Points- Review 2 Arrangement of Lattice Points 3 Arrangement of Lattice Points (continued) •These are known as the basis vectors, which we will come back to. •These are not translation vectors (R) since they have non- integer values. The complexity of the system depends upon the symmetry requirements (is it lost or maintained?) by applying the symmetry operations (rotation, reflection, inversion and translation). 4 The Five 2-D Bravais Lattices •From the previous definitions of the four 2-D and seven 3-D crystal systems, we know that there are four and seven primitive unit cells (with 1 lattice point/unit cell), respectively. •We can then ask: can we add additional lattice points to the primitive lattices (or nets), in such a way that we still have a lattice (net) belonging to the same crystal system (with symmetry requirements)? •First illustrate this for 2-D nets, where we know that the surroundings of each lattice point must be identical. -

The Metrical Matrix in Teaching Mineralogy G. V

THE METRICAL MATRIX IN TEACHING MINERALOGY G. V. GIBBS Department of Geological Sciences & Department of Materials Science and Engineering Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University Blacksburg, VA 24061 [email protected] INTRODUCTION The calculation of the d-spacings, the angles between planes and zones, the bond lengths and angles and other important geometric relationships for a mineral can be a tedious task both for the student and the instructor, particularly when completed with the large as- sortment of trigonometric identities and algebraic formulae that are available (d. Crystal Geometry (1959), Donnay and Donnay, International Tables for Crystallography, Vol. II, Section 3, The Kynoch Press, 101-158). However, such calculations are straightforward and relatively easy to do when completed with the metrical matrix and the interactive software MATOP. Several applications of the matrix are presented below, each of which is worked out in detail and which is designed to teach you its use in the study of crystal geometry. SOME PRELIMINARY COMMENTS We begin our discussion of the matrix with a brief examination of the properties of the geometric three dimensional space, S, in which we live and in which minerals and rocks occur. For our purposes, it will be convenient to view S as the set of all vectors that radiate from a common origin to each point in space. In constructing a model for S, we chose three noncoplanar, coordinate axes denoted X, Y and Z, each radiating from the origin, O. Next, we place three nonzero vectors denoted a, band c along X, Y and Z, respectively, likewise radiating from O. -

Primitive Cell Wigner-Seitz Cell (WS) Primitive Cell

Lecture 4 Jan 16 2013 Primitive cell Primitive cell Wigner-Seitz cell (WS) First Brillouin zone The Wigner-Seitz primitive cell of the reciprocal lattice is known as the first Brillouin zone. (Wigner-Seitz is real space concept while Brillouin zone is a reciprocal space idea). Powder cell Polymorphic Forms of Carbon Graphite – a soft, black, flaky solid, with a layered structure – parallel hexagonal arrays of carbon atoms – weak van der Waal’s forces between layers – planes slide easily over one another Miller indices Simple cubic Miller Indices Rules for determining Miller Indices: 1. Determine the intercepts of the face along the crystallographic axes, in terms of un it ce ll dimens ions. 2. Take the reciprocals 3. Clear fractions 4. Reduce to lowest terms Simple cubic d100=? Where does a protein crystallographer see the Miller indices? CtlCommon crystal faces are parallel to lattice planes • Eac h diffrac tion spo t can be regarded as a X-ray beam reflected from a lattice plane , and therefore has a unique Miller index. Miller indices A Miller index is a series of coprime integers that are inversely ppproportional to the intercepts of the cry stal face or crystallographic planes with the edges of the unit cell. It describes the orientation of a plane in the 3-D lattice with respect to the axes. The general form of the Miller index is (h, k, l) where h, k, and l are integers related to the unit cell along the a, b, c crystal axes. Irreducible brillouin zone II II II II Reciprocal lattice ghakblc The Bravais lattice after Fourier transform real space reciprocal lattice normaltthlls to the planes (vect ors ) poitints spacing between planes 1/distance between points ((y,p)actually, 2p/distance) l (distance, wavelength) 2p/l=k (momentum, wave number) BillBravais cell Wigner-SiSeitz ce ll Brillouin zone . -

Chapter 4, Bravais Lattice Primitive Vectors

Chapter 4, Bravais Lattice A Bravais lattice is the collection of all (and only those) points in space reachable from the origin with position vectors: n , n , n integer (+, -, or 0) r r r r 1 2 3 R = n1a1 + n2 a2 + n3a3 a1, a2, and a3 not all in same plane The three primitive vectors, a1, a2, and a3, uniquely define a Bravais lattice. However, for one Bravais lattice, there are many choices for the primitive vectors. A Bravais lattice is infinite. It is identical (in every aspect) when viewed from any of its lattice points. This is not a Bravais lattice. Honeycomb: P and Q are equivalent. R is not. A Bravais lattice can be defined as either the collection of lattice points, or the primitive translation vectors which construct the lattice. POINT Q OBJECT: Remember that a Bravais lattice has only points. Points, being dimensionless and isotropic, have full spatial symmetry (invariant under any point symmetry operation). Primitive Vectors There are many choices for the primitive vectors of a Bravais lattice. One sure way to find a set of primitive vectors (as described in Problem 4 .8) is the following: (1) a1 is the vector to a nearest neighbor lattice point. (2) a2 is the vector to a lattice points closest to, but not on, the a1 axis. (3) a3 is the vector to a lattice point nearest, but not on, the a18a2 plane. How does one prove that this is a set of primitive vectors? Hint: there should be no lattice points inside, or on the faces (lll)fhlhd(lllid)fd(parallolegrams) of, the polyhedron (parallelepiped) formed by these three vectors. -

Space Symmetry, Space Groups

Space symmetry, Space groups - Space groups are the product of possible combinations of symmetry operations including translations. - There exist 230 different space groups in 3-dimensional space - Comparing to point groups, space groups have 2 more symmetry operations (table 1). These operations include translations. Therefore they describe not only the lattice but also the crystal structure. Table 1: Additional symmetry operations in space symmetry, their description, symmetry elements and Hermann-Mauguin symbols. symmetry H-M description symmetry element operation symbol screw 1. rotation by 360°/N screw axis NM (Schraubung) 2. translation along the axis (Schraubenachse) 1. reflection across the plane glide glide plane 2. translation parallel to the a,b,c,n,d (Gleitspiegelung) (Gleitspiegelebene) glide plane Glide directions for the different gilde planes: a (b,c): translation along ½ a or ½ b or ½ c, respectively) (with ,, cba = vectors of the unit cell) n: translation e.g. along ½ (a + b) d: translation e.g. along ¼ (a + b), d from diamond, because this glide plane occurs in the diamond structure Screw axis example: 21 (N = 2, M = 1) 1) rotation by 180° (= 360°/2) 2) translation parallel to the axis by ½ unit (M/N) Only 21, (31, 32), (41, 43), 42, (61, 65) (62, 64), 63 screw axes exist in parenthesis: right, left hand screw axis Space group symbol: The space group symbol begins with a capital letter (P: primitive; A, B, C: base centred I, body centred R rhombohedral, F face centred), which represents the Bravais lattice type, followed by the short form of symmetry elements, as known from the point group symbols. -

Multidisciplinary Design Project Engineering Dictionary Version 0.0.2

Multidisciplinary Design Project Engineering Dictionary Version 0.0.2 February 15, 2006 . DRAFT Cambridge-MIT Institute Multidisciplinary Design Project This Dictionary/Glossary of Engineering terms has been compiled to compliment the work developed as part of the Multi-disciplinary Design Project (MDP), which is a programme to develop teaching material and kits to aid the running of mechtronics projects in Universities and Schools. The project is being carried out with support from the Cambridge-MIT Institute undergraduate teaching programe. For more information about the project please visit the MDP website at http://www-mdp.eng.cam.ac.uk or contact Dr. Peter Long Prof. Alex Slocum Cambridge University Engineering Department Massachusetts Institute of Technology Trumpington Street, 77 Massachusetts Ave. Cambridge. Cambridge MA 02139-4307 CB2 1PZ. USA e-mail: [email protected] e-mail: [email protected] tel: +44 (0) 1223 332779 tel: +1 617 253 0012 For information about the CMI initiative please see Cambridge-MIT Institute website :- http://www.cambridge-mit.org CMI CMI, University of Cambridge Massachusetts Institute of Technology 10 Miller’s Yard, 77 Massachusetts Ave. Mill Lane, Cambridge MA 02139-4307 Cambridge. CB2 1RQ. USA tel: +44 (0) 1223 327207 tel. +1 617 253 7732 fax: +44 (0) 1223 765891 fax. +1 617 258 8539 . DRAFT 2 CMI-MDP Programme 1 Introduction This dictionary/glossary has not been developed as a definative work but as a useful reference book for engi- neering students to search when looking for the meaning of a word/phrase. It has been compiled from a number of existing glossaries together with a number of local additions. -

Apophyllite-(Kf)

December 2013 Mineral of the Month APOPHYLLITE-(KF) Apophyllite-(KF) is a complex mineral with the unusual tendency to “leaf apart” when heated. It is a favorite among collectors because of its extraordinary transparency, bright luster, well- developed crystal habits, and occurrence in composite specimens with various zeolite minerals. OVERVIEW PHYSICAL PROPERTIES Chemistry: KCa4Si8O20(F,OH)·8H20 Basic Hydrous Potassium Calcium Fluorosilicate (Basic Potassium Calcium Silicate Fluoride Hydrate), often containing some sodium and trace amounts of iron and nickel. Class: Silicates Subclass: Phyllosilicates (Sheet Silicates) Group: Apophyllite Crystal System: Tetragonal Crystal Habits: Usually well-formed, cube-like or tabular crystals with rectangular, longitudinally striated prisms, square cross sections, and steep, diamond-shaped, pyramidal termination faces; pseudo-cubic prisms usually have flat terminations with beveled, distinctly triangular corners; also granular, lamellar, and compact. Color: Usually colorless or white; sometimes pale shades of green; occasionally pale shades of yellow, red, blue, or violet. Luster: Vitreous to pearly on crystal faces, pearly on cleavage surfaces with occasional iridescence. Transparency: Transparent to translucent Streak: White Cleavage: Perfect in one direction Fracture: Uneven, brittle. Hardness: 4.5-5.0 Specific Gravity: 2.3-2.4 Luminescence: Often fluoresces pale yellow-green. Refractive Index: 1.535-1.537 Distinctive Features and Tests: Pseudo-cubic crystals with pearly luster on cleavage surfaces; longitudinal striations; and occurrence as a secondary mineral in association with various zeolite minerals. Laboratory analysis is necessary to differentiate apophyllite-(KF) from closely-related apophyllite-(KOH). Can be confused with such zeolite minerals as stilbite-Ca [hydrous calcium sodium potassium aluminum silicate, Ca0.5,K,Na)9(Al9Si27O72)·28H2O], which forms tabular, wheat-sheaf-like, monoclinic crystals. -

Infrare D Transmission Spectra of Carbonate Minerals

Infrare d Transmission Spectra of Carbonate Mineral s THE NATURAL HISTORY MUSEUM Infrare d Transmission Spectra of Carbonate Mineral s G. C. Jones Department of Mineralogy The Natural History Museum London, UK and B. Jackson Department of Geology Royal Museum of Scotland Edinburgh, UK A collaborative project of The Natural History Museum and National Museums of Scotland E3 SPRINGER-SCIENCE+BUSINESS MEDIA, B.V. Firs t editio n 1 993 © 1993 Springer Science+Business Media Dordrecht Originally published by Chapman & Hall in 1993 Softcover reprint of the hardcover 1st edition 1993 Typese t at the Natura l Histor y Museu m ISBN 978-94-010-4940-5 ISBN 978-94-011-2120-0 (eBook) DOI 10.1007/978-94-011-2120-0 Apar t fro m any fair dealin g for the purpose s of researc h or privat e study , or criticis m or review , as permitte d unde r the UK Copyrigh t Design s and Patent s Act , 1988, thi s publicatio n may not be reproduced , stored , or transmitted , in any for m or by any means , withou t the prio r permissio n in writin g of the publishers , or in the case of reprographi c reproductio n onl y in accordanc e wit h the term s of the licence s issue d by the Copyrigh t Licensin g Agenc y in the UK, or in accordanc e wit h the term s of licence s issue d by the appropriat e Reproductio n Right s Organizatio n outsid e the UK. Enquirie s concernin g reproductio n outsid e the term s state d here shoul d be sent to the publisher s at the Londo n addres s printe d on thi s page. -

Crystal Structure

Physics 927 E.Y.Tsymbal Section 1: Crystal Structure A solid is said to be a crystal if atoms are arranged in such a way that their positions are exactly periodic. This concept is illustrated in Fig.1 using a two-dimensional (2D) structure. y T C Fig.1 A B a x 1 A perfect crystal maintains this periodicity in both the x and y directions from -∞ to +∞. As follows from this periodicity, the atoms A, B, C, etc. are equivalent. In other words, for an observer located at any of these atomic sites, the crystal appears exactly the same. The same idea can be expressed by saying that a crystal possesses a translational symmetry. The translational symmetry means that if the crystal is translated by any vector joining two atoms, say T in Fig.1, the crystal appears exactly the same as it did before the translation. In other words the crystal remains invariant under any such translation. The structure of all crystals can be described in terms of a lattice, with a group of atoms attached to every lattice point. For example, in the case of structure shown in Fig.1, if we replace each atom by a geometrical point located at the equilibrium position of that atom, we obtain a crystal lattice. The crystal lattice has the same geometrical properties as the crystal, but it is devoid of any physical contents. There are two classes of lattices: the Bravais and the non-Bravais. In a Bravais lattice all lattice points are equivalent and hence by necessity all atoms in the crystal are of the same kind.