Sources of Conflict: Highlights from the Managing Chaos Conference

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![Diacronie, N° 29, 1 | 2017, « “Crash Test” » [Online], Messo Online Il 29 Mars 2017, Consultato Il 28 Septembre 2020](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6864/diacronie-n%C2%B0-29-1-2017-%C2%AB-crash-test-%C2%BB-online-messo-online-il-29-mars-2017-consultato-il-28-septembre-2020-226864.webp)

Diacronie, N° 29, 1 | 2017, « “Crash Test” » [Online], Messo Online Il 29 Mars 2017, Consultato Il 28 Septembre 2020

Diacronie Studi di Storia Contemporanea N° 29, 1 | 2017 “Crash test” Continuità, discontinuità, legami e rotture nelle dinamiche della storia contemporanea Redazione di Diacronie (dir.) Edizione digitale URL: http://journals.openedition.org/diacronie/4862 DOI: 10.4000/diacronie.4862 ISSN: 2038-0925 Editore Association culturelle Diacronie Notizia bibliografica digitale Redazione di Diacronie (dir.), Diacronie, N° 29, 1 | 2017, « “Crash test” » [Online], Messo online il 29 mars 2017, consultato il 28 septembre 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/diacronie/4862 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/diacronie.4862 Questo documento è stato generato automaticamente il 28 settembre 2020. Creative Commons License 1 INDICE Nota introduttiva n. 29 – marzo 2017 Jacopo Bassi e Fausto Pietrancosta I. Articoli La Icaria di Étienne Cabet: un’utopia letteraria del XIX secolo José D’Assunção Barros Guerra e miniera in Toscana Il lavoro nel comparto lignitifero durante i due conflitti mondiali Giorgio Sacchetti Un oscuro protagonista dell’affaire Moro: Antonio Chichiarelli e il falso comunicato n. 7 Francesco Landolfi Un largo y sigiloso camino Espionaje e infiltración policial en el mundo estudiantil en la Argentina (1957-1972) Monica Bartolucci “Diplomacias y soberanía” Argentina y Gran Bretaña (1982-1989) Pablo Baisotti II. Tavola rotonda – Wikipedia e le scienze storiche Riflessioni sulla narrazione storica nelle voci di Wikipedia Tommaso Baldo Verso il sapere unico Nicola Strizzolo Dissoluzioni, parodie o mutamenti? Considerazioni sulla storia nelle pagine di Wikipedia Mateus H. F. Pereira Risposta a “Riflessioni sulla narrazione storica nelle voci di Wikipedia” Iolanda Pensa Wikipedia è poco affidabile? La colpa è anche degli esperti Cristian Cenci Danzica e le guerre wikipediane Qualche osservazione sulle edit wars Jacopo Bassi Considerazioni conclusive Riflessioni sulla narrazione storica nelle voci di Wikipedia Tommaso Baldo Diacronie, N° 29, 1 | 2017 2 III. -

Destructive Discourse

Destructive Discourse ‘Japan-bashing’ in the United States, Australia and Japan in the 1980s and 1990s This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of Murdoch University 2006 Narrelle Morris (LLB, BAsian St., BA (Hons), Murdoch University) I declare that this thesis is my own account of my research and contains as its main content work which has not previously been submitted for a degree at any tertiary education institution. ...................... ABSTRACT By the 1960s-70s, most Western commentators agreed that Japan had rehabilitated itself from World War II, in the process becoming on the whole a reliable member of the international community. From the late 1970s onwards, however, as Japan’s economy continued to rise, this premise began to be questioned. By the late 1980s, a new ‘Japan Problem’ had been identified in Western countries, although the presentation of Japan as a dangerous ‘other’ was nevertheless familiar from past historical eras. The term ‘Japan-bashing’ was used by opponents of this negative view to suggest that much of the critical rhetoric about a ‘Japan Problem’ could be reduced to an unwarranted, probably racist, assault on Japan. This thesis argues that the invention and popularisation of the highly-contested label ‘Japan-bashing’, rather than averting criticism of Japan, perversely helped to exacerbate and transform the moderate anti-Japanese sentiment that had existed in Western countries in the late 1970s and early 1980s into a widely disseminated, heavily politicised and even encultured phenomenon in the late 1980s and 1990s. Moreover, when the term ‘Japan-bashing’ spread to Japan itself, Japanese commentators were quick to respond. -

The Midwest 9/11 Truth Conference, 2013 Event Videos Now on Youtube

This version of Total HTML Converter is unregistered. NewsFollowup Franklin Scandal Omaha Sitemap Obama Comment Search Pictorial index home Midwest 9/11 Truth Go to Midwest 9/11 Truth Conference The Midwest 9/11 Truth Conference 2014 page Architects & Engineers Conference, 2013 for 9/11 Truth Mini / Micro Nukes 9/11 Truth links Event videos now on YouTube, World911Truth Cheney, Planning and Decision Aid System speakers: Sonnenfeld Video of 9/11 Ground Zero Victims and Rescuers Wayne Madsen , Investigative Journalist, and 9/11 Whistleblowers AE911Truth James Fetzer, Ph.D., Founder of Scholars for 9/11 Truth Ed Asner Contact: Steve Francis Compare competing Kevin Barrett, co-founder Muslim Jewish Christian Alliance for 9/11 Truth [email protected] theories The Midwest 9/11 Truth Conference 2014 is now in the planning stages. Top 9/11 Documentaries US/British/Saudi/Zionists Research Speakers: The Midwest 9/11 Wayne Madsen Truth Conference Jim Fetzer Wayne Madsen is a Washington, DC-based investigative James H. Fetzer, a former Marine Corps officer, is This version of Total HTML Converter is unregistered. journalist, author and columnist. He has written for The Village Distinguished McKnight Professor Emeritus on the Duluth Voice, The Progressive, Counterpunch, Online Journal, campus of the University of Minnesota. A magna cum CorpWatch, Multinational Monitor, News Insider, In These laude in philosophy graduate of Princeton University in Times, and The American Conservative. His columns have 1962, he was commissioned as a 2nd Lieutenant and appeared in The Miami Herald, Houston Chronicle, became an artillery officer who served in the Far East. Philadelphia Inquirer, Columbus Dispatch, Sacramento Bee, After a tour supervising recruit training in San Diego, he and Atlanta Journal-Constitution, among others. -

Desired Ground Zeroes: Nuclear Imagination and the Death Drive Calum Lister Matheson a Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty At

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Carolina Digital Repository Desired Ground Zeroes: Nuclear Imagination and the Death Drive Calum Lister Matheson A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Communication Studies. Chapel Hill 2015 Approved by: Carole Blair Ken Hillis Chris Lundberg Todd Ochoa Sarah Sharma © 2015 Calum Lister Matheson ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Calum Lister Matheson: Desired Ground Zeroes: Nuclear Imagination and the Death Drive (Under the direction of Chris Lundberg and Sarah Sharma) A wide variety of cultural artefacts related to nuclear warfare are examined to highlight continuity in the sublime’s mix of horror and fascination. Schemes to use nuclear explosions for peaceful purposes embody the godlike structural positions of the Bomb for Americans in the early Cold War. Efforts to mediate the Real of the Bomb include nuclear simulations used in wargames and their civilian offshoots in videogames and other media. Control over absence is examined through the spatial distribution of populations that would be sacrificed in a nuclear war and appeals to overarching rationality to justify urban inequality. Control over presence manifests in survivalism, from Cold War shelter construction to contemporary “doomsday prepping” and survivalist novels. The longstanding cultural ambivalence towards nuclear war, coupled with the manifest desire to experience the Real, has implications for nuclear activist strategies that rely on democratically-engaged publics to resist nuclear violence once the “truth” is made clear. -

Cassette Books, CMLS,P.O

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 319 210 EC 230 900 TITLE Cassette ,looks. INSTITUTION Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. National Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapped. PUB DATE 8E) NOTE 422p. AVAILABLE FROMCassette Books, CMLS,P.O. Box 9150, M(tabourne, FL 32902-9150. PUB TYPE Reference Materials Directories/Catalogs (132) --- Reference Materials Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC17 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Adults; *Audiotape Recordings; *Blindness; Books; *Physical Disabilities; Secondary Education; *Talking Books ABSTRACT This catalog lists cassette books produced by the National Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapped during 1989. Books are listed alphabetically within subject categories ander nonfiction and fiction headings. Nonfiction categories include: animals and wildlife, the arts, bestsellers, biography, blindness and physical handicaps, business andeconomics, career and job training, communication arts, consumerism, cooking and food, crime, diet and nutrition, education, government and politics, hobbies, humor, journalism and the media, literature, marriage and family, medicine and health, music, occult, philosophy, poetry, psychology, religion and inspiration, science and technology, social science, space, sports and recreation, stage and screen, traveland adventure, United States history, war, the West, women, and world history. Fiction categories includer adventure, bestsellers, classics, contemporary fiction, detective and mystery, espionage, family, fantasy, gothic, historical fiction, -

Interview with Ambassador Henry Allen Holmes

Library of Congress Interview with Ambassador Henry Allen Holmes The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training Foreign Affairs Oral History Project AMBASSADOR HENRY ALLEN HOLMES Interviewed by: Charles Stuart Kennedy Initial interview date: March 9, 1999 Copyright 2009 ADST Q: Today is March 9, 1999. This is an interview with Henry Allen Holmes. This is being done on behalf of the Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training, and I'm Charles Stuart Kennedy. Allen, I want to start with the beginning. Could you tell me when and where you were born and then something about your parents? HOLMES: I was born the day that Hitler became chancellor of Germany, January 31, 1933, in Bucharest, Rumania, at the American legation, where my dad, Julius Cecil Holmes, was the charg# at the time. He was the number two guy in a two-guy legation, and the night that I was born he was getting phone calls from Foreign Service colleagues all over Western Europe wondering what the king of Rumania's move was going to be now that Hitler had become chancellor of Germany. Q: So you and Hitler sort of rose to power at the same time. HOLMES: Be careful in this interview. We have the same initials - A. H. Q: Could you tell me a bit about the background of your father and the background of your mother, please? Interview with Ambassador Henry Allen Holmes http://www.loc.gov/item/mfdipbib001561 Library of Congress HOLMES: My mother and father were both born and raised in Kansas. They went to Kansas University in Lawrence, Kansas, where my dad spent most of his life growing up. -

Item More Personal, More Unique, And, Therefore More Representative of the Experience of the Book Itself

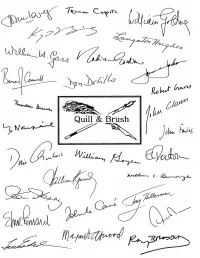

Q&B Quill & Brush (301) 874-3200 Fax: (301)874-0824 E-mail: [email protected] Home Page: http://www.qbbooks.com A dear friend of ours, who is herself an author, once asked, “But why do these people want me to sign their books?” I didn’t have a ready answer, but have reflected on the question ever since. Why Signed Books? Reading is pure pleasure, and we tend to develop affection for the people who bring us such pleasure. Even when we discuss books for a living, or in a book club, or with our spouses or co- workers, reading is still a very personal, solo pursuit. For most collectors, a signature in a book is one way to make a mass-produced item more personal, more unique, and, therefore more representative of the experience of the book itself. Few of us have the opportunity to meet the authors we love face-to-face, but a book signed by an author is often the next best thing—it brings us that much closer to the author, proof positive that they have held it in their own hands. Of course, for others, there is a cost analysis, a running thought-process that goes something like this: “If I’m going to invest in a book, I might as well buy a first edition, and if I’m going to invest in a first edition, I might as well buy a signed copy.” In other words we want the best possible copy—if nothing else, it is at least one way to hedge the bet that the book will go up in value, or, nowadays, retain its value. -

Lawsuit and Retracts Comments About Refugees in Twin Falls, Idaho, L.A

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE WESTERN DISTRICT OF VIRGINIA Charlottesville Division _______________________________________ ) BRENNAN M. GILMORE, ) ) Plaintiff ) Case No. ______________ ) v. ) ) ALEXANDER (“ALEX”) E. JONES; ) INFOWARS, LLC, a Texas Limited Liability ) JURY TRIAL DEMANDED Company; FREE SPEECH SYSTEMS, LLC, a ) Texas Limited Liability Company; LEE ) STRANAHAN; LEE ANN MCADOO A/K/A ) LEE ANN FLEISSNER; ) SCOTT CREIGHTON; JAMES (“JIM”) ) HOFT; ALLEN B. WEST; and DERRICK ) WILBURN, ) ) Defendants. ) __________________________________________) COMPLAINT NOW COMES Plaintiff Brennan Gilmore, by and through undersigned counsel, and alleges upon knowledge and belief as follows: I. INTRODUCTION Brennan Gilmore works to provide jobs and training in rural areas, participates in local politics, and plays music around the Commonwealth of Virginia. As a Foreign Service Officer, Mr. Gilmore has devoted his career to promoting United States interests and to protecting American citizens through diplomatic efforts abroad. On August 12, 2017, Mr. Gilmore witnessed firsthand James Alex Fields Jr., a neo-Nazi, deliberately drive his Dodge Challenger into a crowd of peaceful protesters, killing Heather Heyer and injuring many others. Mr. Gilmore, who had been filming the protesters as they moved up the street, happened to catch Fields’ attack on video. Mr. 1 Gilmore posted the video on Twitter, where it attracted the attention of the press. After discussing what he had witnessed that day with a number of reporters, Mr. Gilmore soon became the target of right-wing conspiracy theories. Supporters of the alt-right and the “Unite the Right rally,” including the defendants, created a new identity for Mr. Gilmore—the organizer and orchestrator of Fields’ attack and a traitor to the United States. -

TERROR VANQUISHED the Italian Approach to Defeating Terrorism

TERROR VANQUISHED The Italian Approach to Defeating Terrorism SIMON CLARK at George Mason University TERROR VANQUISHED The Italian Approach to Defeating Terrorism Simon Clark Copyright ©2018 Center for Security Policy Studies, Schar School of Policy and Government, George Mason University Library of Congress Control Number: 2018955266 ISBN: 978-1-7329478-0-1 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without written permission from: The Center for Security Policy Studies Schar School of Policy and Government George Mason University 3351 Fairfax Avenue Arlington, Virginia 22201 www.csps.gmu.edu PHOTO CREDITS Cover: Dino Fracchia / Alamy Stock Photo Page 30: MARKA / Alamy Stock Photo Page 60: The Picture Art Collection / Alamy Stock Photo Page 72: Dino Fracchia / Alamy Stock Photo Page 110: Dino Fracchia / Alamy Stock Photo Publication design by Lita Ledesma Contents Foreword 5 Preface 7 Introduction 11 Chapter 1: The Italian Approach to Counter-Terrorism 21 Chapter 2: Post War Italian Politics: Stasis And Chaos 31 Chapter 3: The Italian Security Apparatus 43 Chapter 4: Birth of the Red Brigades: Years of Lead 49 Chapter 5: Attacking the Heart of the State 61 Chapter 6: Escalation, Repentance, Defeat 73 Chapter 7: State Sponsorship: a Comforting Illusion 81 Chapter 8: A Strategy for Psychological Warfare 91 Chapter 9: Conclusion: Defeating A Terrorist Threat 111 Bibliography 119 4 Terror Vanquished: The Italian Approach to Defeating Terrorism Foreword 5 Foreword It is my pleasure to introduce Terrorism Vanquished: the Italian Approach to Defeating Terror, by Simon Clark. In this compelling analysis, Mr. -

Obama Is Rigging the Election !

11/26/2017 Americans for Innovation: RED ALERT: OBAMA IS RIGGING THE ELECTION ! More Next Blog» [email protected] New Post Design Sign Out SEARCH by topic, keyword or phrase. Type in Custom Search box e.g. "IBM Eclipse Foundation" or "racketeering" Custom Search Tuesday, November 1, 2016 DEEP STATE Member SHADOW RED ALERT: OBAMA IS RIGGING THE ELECTION ! GOVERNMENT IN 2009 HILLARY BANKROLLED FACEBOOK’S ELECTION RIGGING SOFTWARE POSTER Harvard | Yale | Stanford Sycophants IN 2014 OBAMA BANKROLLED “THE ERIC SCHMIDT PROJECT” (GOOGLE) Updated Nov. 25, 2017. BIG BROTHER DNC DATABASE (HATCH ACT VIOLATION) CLICK HERE TO SEE COMBINED TIMELINE OF THE IN OCT 2014 OBAMA SENT TODD PARK TO SILICON VALLEY TO WORK FOR HILLARY AND IMPLEMENT HILLARY’S FACEBOOK ELECTION RIGGING HIJACKING OF THE INTERNET SOFTWARE PAY-to-PLA Y NEW W ORLD ORDER This timeline shows how insiders sell access OBAMA IS SET TO FIX THE ELECTION FROM THE WHITE HOUSE & manipulate politicians, police, intelligence, judges and media to keep their secrets CONTRIBUTING WRITERS | OPINION | AMERICANS FOR INNOVATION | NOV. 01, 2016, NOV. 26, 2017 | PDF Clintons, Obamas, Summers were paid in cash for outlandish speaking fees and Foundation donations. Sycophant judges, politicians, academics, bureaucrats and media were fed tips to mutual funds tied to insider stocks like Facebook. Risk of public exposure, blackmail, pedophilia, “snuff parties” (ritual child sexual abuse and murder) and Satanism have ensured silence among pay-to-play beneficiaries. The U.S. Patent Office is their toy box from which to steal new ideas. FIG. 1: BARACK OBAMA is using taxpayer funds to rig the 2016 election. -

Leonardo Sciascia E La Funzione Sociale Degli Intellettuali

STUDI E SAGGI – 105 – STUDI DI ITALIANISTICA MODERNA E CONTEMPORANEA NEL MONDO ANGLOFONO STUDIes IN MODERN AND CONTEMPORARY ITALIANISTICA IN THE ANGLOPHONE WORLD Comitato scientifico / Editorial Board Joseph Francese, Direttore / Editor-in-chief (Michigan State University) Norma Bouchard (University of Connecticut at Storrs) Joseph A. Buttigieg (University of Notre Dame) Michael Caesar (University of Birmingham) Derek Duncan (University of Bristol) Stephen Gundle (University of Warwick) Marcia Landy (University of Pittsburgh) Silvestra Mariniello (Université de Montréal) Annamaria Pagliaro (Monash University) Lucia Re (University of California at Los Angeles) Silvia Ross (University College Cork) Suzanne Stewart-Steinberg (Brown University) Joseph Francese Leonardo Sciascia e la funzione sociale degli intellettuali FIRENZE UNIVERSITY PRess 2012 Leonardo Sciascia e la funzione sociale degli intellettuali / Joseph Francese. – Firenze : Firenze University Press, 2012. (Studi e saggi ; 105) http://digital.casalini.it/9788866551447 ISBN 978-88-6655-141-6 (print) ISBN 978-88-6655-144-7 (online PDF) ISBN 978-88-6655-146-1 (online EPUB) Progetto grafico di Alberto Pizarro Fernández Immagine di copertina: © Photoeuphoria | Dreamstime.com Certificazione scientifica delle Opere Tutti i volumi pubblicati sono soggetti ad un processo di referaggio esterno di cui sono responsabili il Consiglio editoriale della FUP e i Consigli scientifici delle singole collane. Le opere pubblicate nel catalogo della FUP sono valutate e approvate dal Consiglio editoriale della casa editrice. Per una descrizione più analitica del processo di referaggio si rimanda ai documenti ufficiali pubblicati sul sito-catalogo della casa editrice (http://www.fupress.com). Consiglio editoriale Firenze University Press G. Nigro (Coordinatore), M.T. Bartoli, M. Boddi, F. Cambi, R. -

Henry A. Kissinger

8/26/2020 Americans for Innovation: HENRY KISSINGER HAS BEEN SPYING FOR THE (BRITISH) PILGRIMS SOCIETY, LIKELY SINCE THE LA… More To ensure you are reading the latest post, click the logo above. SEARCH by topic, keyword or phrase. Type in Custom Search box e.g. "IBM Eclipse Foundation" or "racketeering" Wednesday, August 26, 2020 SENIOR EXECUTIVE SERVICE (SES) HENRY KISSINGER HAS BEEN SPYING FOR THE HIJACKED THE INTERNET (BRITISH) PILGRIMS SOCIETY, LIKELY SINCE THE Michael McKibben EXPOS… LATE 1940s CONTRIBUTING WRITERS | OPINION | AMERICANS FOR INNOVATION | AUG. 26, 2020 | PDF | https://tinyurl.com/y347tan4 BREAKING HISTORICAL NEWS! Click here to download a raw *.mp4 version of this video DEEP STATE Member KISSINGER SOLD OUT AMERICA ON SHADOW ORDERS FROM THE PILGRIMS SOCIETY GOVERNMENT POSTER Harvard | Yale | Stanford | Oxbridge (Cambridge, Oxford) | Sycophants LEGEND: Some corruptocrat photos in this blog contain a stylized Christian Celtic Wheel Cross in the background alongside the text "Corruption Central" meaning we have put the person's conduct under the microscope and discovered that he or she is at the center of global corruption. Judge Amy Berman Jackson asserts that it is unambiguously (to her anyway) a rifle cross hair. This shows her woeful ignorance of theology, history, symbology and engineering. It could be many things, but she clearly wanted to see a rifle sight (ask her about her role in Fast and Furious gun running). Others assert equally ignorantly that it is a pagan Fig. 1—Henry Alfred Kissinger (b. May 27, 1923, Fuerth, Germany; naturalized U.S. citizen Jun. or white supremacist symbol. This stylized Christian Chi- Rho Cross dates to 312 A.D.