Interview with Ambassador Henry Allen Holmes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![Diacronie, N° 29, 1 | 2017, « “Crash Test” » [Online], Messo Online Il 29 Mars 2017, Consultato Il 28 Septembre 2020](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6864/diacronie-n%C2%B0-29-1-2017-%C2%AB-crash-test-%C2%BB-online-messo-online-il-29-mars-2017-consultato-il-28-septembre-2020-226864.webp)

Diacronie, N° 29, 1 | 2017, « “Crash Test” » [Online], Messo Online Il 29 Mars 2017, Consultato Il 28 Septembre 2020

Diacronie Studi di Storia Contemporanea N° 29, 1 | 2017 “Crash test” Continuità, discontinuità, legami e rotture nelle dinamiche della storia contemporanea Redazione di Diacronie (dir.) Edizione digitale URL: http://journals.openedition.org/diacronie/4862 DOI: 10.4000/diacronie.4862 ISSN: 2038-0925 Editore Association culturelle Diacronie Notizia bibliografica digitale Redazione di Diacronie (dir.), Diacronie, N° 29, 1 | 2017, « “Crash test” » [Online], Messo online il 29 mars 2017, consultato il 28 septembre 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/diacronie/4862 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/diacronie.4862 Questo documento è stato generato automaticamente il 28 settembre 2020. Creative Commons License 1 INDICE Nota introduttiva n. 29 – marzo 2017 Jacopo Bassi e Fausto Pietrancosta I. Articoli La Icaria di Étienne Cabet: un’utopia letteraria del XIX secolo José D’Assunção Barros Guerra e miniera in Toscana Il lavoro nel comparto lignitifero durante i due conflitti mondiali Giorgio Sacchetti Un oscuro protagonista dell’affaire Moro: Antonio Chichiarelli e il falso comunicato n. 7 Francesco Landolfi Un largo y sigiloso camino Espionaje e infiltración policial en el mundo estudiantil en la Argentina (1957-1972) Monica Bartolucci “Diplomacias y soberanía” Argentina y Gran Bretaña (1982-1989) Pablo Baisotti II. Tavola rotonda – Wikipedia e le scienze storiche Riflessioni sulla narrazione storica nelle voci di Wikipedia Tommaso Baldo Verso il sapere unico Nicola Strizzolo Dissoluzioni, parodie o mutamenti? Considerazioni sulla storia nelle pagine di Wikipedia Mateus H. F. Pereira Risposta a “Riflessioni sulla narrazione storica nelle voci di Wikipedia” Iolanda Pensa Wikipedia è poco affidabile? La colpa è anche degli esperti Cristian Cenci Danzica e le guerre wikipediane Qualche osservazione sulle edit wars Jacopo Bassi Considerazioni conclusive Riflessioni sulla narrazione storica nelle voci di Wikipedia Tommaso Baldo Diacronie, N° 29, 1 | 2017 2 III. -

Destructive Discourse

Destructive Discourse ‘Japan-bashing’ in the United States, Australia and Japan in the 1980s and 1990s This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of Murdoch University 2006 Narrelle Morris (LLB, BAsian St., BA (Hons), Murdoch University) I declare that this thesis is my own account of my research and contains as its main content work which has not previously been submitted for a degree at any tertiary education institution. ...................... ABSTRACT By the 1960s-70s, most Western commentators agreed that Japan had rehabilitated itself from World War II, in the process becoming on the whole a reliable member of the international community. From the late 1970s onwards, however, as Japan’s economy continued to rise, this premise began to be questioned. By the late 1980s, a new ‘Japan Problem’ had been identified in Western countries, although the presentation of Japan as a dangerous ‘other’ was nevertheless familiar from past historical eras. The term ‘Japan-bashing’ was used by opponents of this negative view to suggest that much of the critical rhetoric about a ‘Japan Problem’ could be reduced to an unwarranted, probably racist, assault on Japan. This thesis argues that the invention and popularisation of the highly-contested label ‘Japan-bashing’, rather than averting criticism of Japan, perversely helped to exacerbate and transform the moderate anti-Japanese sentiment that had existed in Western countries in the late 1970s and early 1980s into a widely disseminated, heavily politicised and even encultured phenomenon in the late 1980s and 1990s. Moreover, when the term ‘Japan-bashing’ spread to Japan itself, Japanese commentators were quick to respond. -

Henry Justin Allen

Henry Justin Allen "The Tragedy of Transportation" Address by Hon. Henry J. Allen before Illinois Manufacturers Association, Chicago May 23, 1922 Forty-three million people live in the territory served by the Great Lakes. Half of them are farmers. Agricultural prosperity, which is the fundamental basis of all prosperity, is measured by the difference between farming cost and the price of farm products. It is generally a thin margin. For the five-year period ending with 1917, the average profit on corn was 11¢, on wheat 7¢ in states like Minnesota, Iowa, Dakota and Montana. Similar figures are doubtless correct for the other agricultural states. Nothing has struck the farm profits a blow so paralyzing as the increased cost of transportation. The farmer in central Iowa, shipping oats to the Atlantic seaboard, gets paid for one bushel in three. The cost of transportation takes the other two bushels. The farm price is the market price with transportation deducted and the export market, where the surplus is sold, sets the price for the whole crop. Wheat in Kansas and Nebraska is further from the New York market than wheat on the Argentine farm. You can move Argentine wheat by its short rail haul to the post, ship it to New York, carry it inland to a mill and ship it back to New York as flour before the transportation charge equals the freight on wheat from the west to the Atlantic seaboard. Wheat from Nebraska, in export movement, goes to the nearest lake port, by water to the foot of Lake Erie, thence to New York for shipment abroad. -

List of Freemasons from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia Jump To: Navigation , Search

List of Freemasons From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Jump to: navigation , search Part of a series on Masonic youth organizations Freemasonry DeMolay • A.J.E.F. • Job's Daughters International Order of the Rainbow for Girls Core articles Views of Masonry Freemasonry • Grand Lodge • Masonic • Lodge • Anti-Masonry • Anti-Masonic Party • Masonic Lodge Officers • Grand Master • Prince Hall Anti-Freemason Exhibition • Freemasonry • Regular Masonic jurisdictions • Opposition to Freemasonry within • Christianity • Continental Freemasonry Suppression of Freemasonry • History Masonic conspiracy theories • History of Freemasonry • Liberté chérie • Papal ban of Freemasonry • Taxil hoax • Masonic manuscripts • People and places Masonic bodies Masonic Temple • James Anderson • Masonic Albert Mackey • Albert Pike • Prince Hall • Masonic bodies • York Rite • Order of Mark Master John the Evangelist • John the Baptist • Masons • Holy Royal Arch • Royal Arch Masonry • William Schaw • Elizabeth Aldworth • List of Cryptic Masonry • Knights Templar • Red Cross of Freemasons • Lodge Mother Kilwinning • Constantine • Freemasons' Hall, London • House of the Temple • Scottish Rite • Knight Kadosh • The Shrine • Royal Solomon's Temple • Detroit Masonic Temple • List of Order of Jesters • Tall Cedars of Lebanon • The Grotto • Masonic buildings Societas Rosicruciana • Grand College of Rites • Other related articles Swedish Rite • Order of St. Thomas of Acon • Royal Great Architect of the Universe • Square and Compasses Order of Scotland • Order of Knight Masons • Research • Pigpen cipher • Lodge • Corks Eye of Providence • Hiram Abiff • Masonic groups for women Sprig of Acacia • Masonic Landmarks • Women and Freemasonry • Order of the Amaranth • Pike's Morals and Dogma • Propaganda Due • Dermott's Order of the Eastern Star • Co-Freemasonry • DeMolay • Ahiman Rezon • A.J.E.F. -

The Midwest 9/11 Truth Conference, 2013 Event Videos Now on Youtube

This version of Total HTML Converter is unregistered. NewsFollowup Franklin Scandal Omaha Sitemap Obama Comment Search Pictorial index home Midwest 9/11 Truth Go to Midwest 9/11 Truth Conference The Midwest 9/11 Truth Conference 2014 page Architects & Engineers Conference, 2013 for 9/11 Truth Mini / Micro Nukes 9/11 Truth links Event videos now on YouTube, World911Truth Cheney, Planning and Decision Aid System speakers: Sonnenfeld Video of 9/11 Ground Zero Victims and Rescuers Wayne Madsen , Investigative Journalist, and 9/11 Whistleblowers AE911Truth James Fetzer, Ph.D., Founder of Scholars for 9/11 Truth Ed Asner Contact: Steve Francis Compare competing Kevin Barrett, co-founder Muslim Jewish Christian Alliance for 9/11 Truth [email protected] theories The Midwest 9/11 Truth Conference 2014 is now in the planning stages. Top 9/11 Documentaries US/British/Saudi/Zionists Research Speakers: The Midwest 9/11 Wayne Madsen Truth Conference Jim Fetzer Wayne Madsen is a Washington, DC-based investigative James H. Fetzer, a former Marine Corps officer, is This version of Total HTML Converter is unregistered. journalist, author and columnist. He has written for The Village Distinguished McKnight Professor Emeritus on the Duluth Voice, The Progressive, Counterpunch, Online Journal, campus of the University of Minnesota. A magna cum CorpWatch, Multinational Monitor, News Insider, In These laude in philosophy graduate of Princeton University in Times, and The American Conservative. His columns have 1962, he was commissioned as a 2nd Lieutenant and appeared in The Miami Herald, Houston Chronicle, became an artillery officer who served in the Far East. Philadelphia Inquirer, Columbus Dispatch, Sacramento Bee, After a tour supervising recruit training in San Diego, he and Atlanta Journal-Constitution, among others. -

Desired Ground Zeroes: Nuclear Imagination and the Death Drive Calum Lister Matheson a Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty At

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Carolina Digital Repository Desired Ground Zeroes: Nuclear Imagination and the Death Drive Calum Lister Matheson A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Communication Studies. Chapel Hill 2015 Approved by: Carole Blair Ken Hillis Chris Lundberg Todd Ochoa Sarah Sharma © 2015 Calum Lister Matheson ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Calum Lister Matheson: Desired Ground Zeroes: Nuclear Imagination and the Death Drive (Under the direction of Chris Lundberg and Sarah Sharma) A wide variety of cultural artefacts related to nuclear warfare are examined to highlight continuity in the sublime’s mix of horror and fascination. Schemes to use nuclear explosions for peaceful purposes embody the godlike structural positions of the Bomb for Americans in the early Cold War. Efforts to mediate the Real of the Bomb include nuclear simulations used in wargames and their civilian offshoots in videogames and other media. Control over absence is examined through the spatial distribution of populations that would be sacrificed in a nuclear war and appeals to overarching rationality to justify urban inequality. Control over presence manifests in survivalism, from Cold War shelter construction to contemporary “doomsday prepping” and survivalist novels. The longstanding cultural ambivalence towards nuclear war, coupled with the manifest desire to experience the Real, has implications for nuclear activist strategies that rely on democratically-engaged publics to resist nuclear violence once the “truth” is made clear. -

Cassette Books, CMLS,P.O

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 319 210 EC 230 900 TITLE Cassette ,looks. INSTITUTION Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. National Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapped. PUB DATE 8E) NOTE 422p. AVAILABLE FROMCassette Books, CMLS,P.O. Box 9150, M(tabourne, FL 32902-9150. PUB TYPE Reference Materials Directories/Catalogs (132) --- Reference Materials Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC17 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Adults; *Audiotape Recordings; *Blindness; Books; *Physical Disabilities; Secondary Education; *Talking Books ABSTRACT This catalog lists cassette books produced by the National Library Service for the Blind and Physically Handicapped during 1989. Books are listed alphabetically within subject categories ander nonfiction and fiction headings. Nonfiction categories include: animals and wildlife, the arts, bestsellers, biography, blindness and physical handicaps, business andeconomics, career and job training, communication arts, consumerism, cooking and food, crime, diet and nutrition, education, government and politics, hobbies, humor, journalism and the media, literature, marriage and family, medicine and health, music, occult, philosophy, poetry, psychology, religion and inspiration, science and technology, social science, space, sports and recreation, stage and screen, traveland adventure, United States history, war, the West, women, and world history. Fiction categories includer adventure, bestsellers, classics, contemporary fiction, detective and mystery, espionage, family, fantasy, gothic, historical fiction, -

National Register Nomination

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register Listed – October 8, 2014 National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin, How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional certification comments, entries, and narrative items on continuation sheets if needed (NPS Form 10-900a). 1. Name of Property Historic name Masonic Grand Lodge Building Other names/site number Masonic Grand Lodge Office and Library, MW Grand Lodge of Kansas Library and Museum, Grand Lodge AF & AM of Kansas; KHRI # 177-2617 Name of related Multiple Property Listing N/A 2. Location th Street & number 320 SW 8 Avenue not for publication City or town Topeka vicinity State Kansas Code KS County Shawnee Code 177 Zip code 66603 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this x nomination _ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional -

Masonic Grand Lodge Building OMB No. 1024 0018

- .. - ~ . -· NPS Form 10-900 0MB No. 1t ;:;~EIVE0221JO United States Department of the Interior National Park Service I AUG 2 2 2014 National Register of Historic Places Registration Fot ~ msTEROFHISTORICPLAcEs This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions l~N ~ ~~B~~~Ki~VIC ~ ow to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional certification comments, entries, and narrative items on continuation sheets if needed (NPS Form 10-900a). 1. Name of Property Historic name Masonic Grand Lodge Building Other names/site number Masonic Grand Lodge Office and Library, MW Grand Lodge of Kansas Library and Museum, Grand Lodge AF & AM of Kansas; KHRI # 177-2617 Name of related Multiple Property Listing _N_/A______________________ ____ 2. Location Street & number 320 SW 8th Avenue not for publication City or town Topeka vicinity -~-----------------------------'------' State Kansas Code KS County -----Shawnee -------Code 177 Zip code 66603 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this _x_ nomination _ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property _x_ meets __ does not meet the National Register Criteria. -

Catalogand Student Handbook

Catalog and Student Handbook College of Arts and Sciences School of Education Undergraduate Programs 2019-2020 bakerU.edu TABLE OF CONTENTS i THE UNIVERSITY .................................................................................................................... 1 Vision, Purpose, Mission, and Values ........................................................................................................... 1 Structure of the University.............................................................................................................................. 1 Accreditation ..................................................................................................................................................... 2 History ............................................................................................................................................................... 2 Facilities and Locations ................................................................................................................................... 3 Ethics and Compliance Policies ..................................................................................................................... 5 Catalog Policies and Student Responsibilities ............................................................................................. 6 Grading System and Practice .......................................................................................................................... 7 Undergraduate Academic Honors .............................................................................................................. -

2017 Molina Michael.Pdf (2.335Mb)

UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE RADICAL REACTIONS: THE FIRST RED SCARE IN THE GREAT PLAINS AND THE U.S.-MEXICO BORDERLANDS, 1918-1920 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY By MICHAEL MOLINA Norman, Oklahoma 2017 © Copyright by MICHAEL MOLINA 2017 All Rights Reserved. Acknowledgements I would like to acknowledge my committee, namely, chair Dr. Sterling Evans, Dr. Elyssa Faison, Dr. Ben Keppel, and Dr. David Wrobel for providing support and guidance through this long process. I would also like to thank my loving and amazingly supportive wife, Kayla Griffis Molina, whose faith and encouragement made everything infinitely more doable. Without her steadfast support, and grueling enforcement of studying, I would have never passed comps and gotten this far. I love you sweety! Similarly, I wish to thank my faithful research buddy and seminar comrade, Matt Corpolongo. His keen insight and political commentaries helped shape my perceptions and gave me a unique perspective. Lastly, I would like to thank my family. To my dad, Arnie Molina, who provided invaluable assistance in Austin and made a great research partner. To my mom, Cherye Molina, whose constant love and prayers made all the difference. To my brother, Matthew Molina, whose encouragement and dry humor made thing bearable. And finally, to my grandma, Georgia Maria Hale, whose unwavering faith and daily prayer helped more than she will ever know. I stand on the shoulders of giants, and without the love, faith, and support from my advisors, friends, and family, none of this would have been possible. -

Item More Personal, More Unique, And, Therefore More Representative of the Experience of the Book Itself

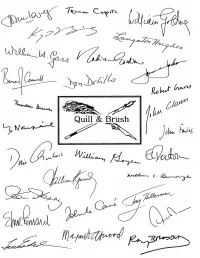

Q&B Quill & Brush (301) 874-3200 Fax: (301)874-0824 E-mail: [email protected] Home Page: http://www.qbbooks.com A dear friend of ours, who is herself an author, once asked, “But why do these people want me to sign their books?” I didn’t have a ready answer, but have reflected on the question ever since. Why Signed Books? Reading is pure pleasure, and we tend to develop affection for the people who bring us such pleasure. Even when we discuss books for a living, or in a book club, or with our spouses or co- workers, reading is still a very personal, solo pursuit. For most collectors, a signature in a book is one way to make a mass-produced item more personal, more unique, and, therefore more representative of the experience of the book itself. Few of us have the opportunity to meet the authors we love face-to-face, but a book signed by an author is often the next best thing—it brings us that much closer to the author, proof positive that they have held it in their own hands. Of course, for others, there is a cost analysis, a running thought-process that goes something like this: “If I’m going to invest in a book, I might as well buy a first edition, and if I’m going to invest in a first edition, I might as well buy a signed copy.” In other words we want the best possible copy—if nothing else, it is at least one way to hedge the bet that the book will go up in value, or, nowadays, retain its value.