How Does the Use of a Social Studies Video Game Affect Student Learning?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Using Game Design and Game Elements in the EFL Classroom ======

>GAMIFICATION ========================================================== >Using game design and game elements in the EFL classroom_ ========================================================== Figure 1 Alien by Illaria Bernareggi / The Noun Project Gilles Glod professeur-candidat Lycée Technique de Bonnevoie Declaration of originality I certify that all material contained in this travail de candidature is my own work. All source material is clearly acknowledged as and when it occurs in the references, as well as in the list of works cited. Luxembourg, 4th November 2017 2 Gilles Glod professeur-candidat au Lycée Technique de Bonnevoie Gamification: using game design and game elements in the EFL classroom Bonnevoie, 2017 3 Abstract Research objectives This thesis discusses the ways in which one of the basic human instincts – the urge to play – can be used in an EFL classroom to improve learners’ motivation, social skills and willingness to engage in language learning. My thesis focuses on three major aspects. First, in my lessons, I have implemented games as well as features that often form the core of games, such as rules of play, experience points, achievements, and the levelling up and customization of an avatar. The learners see their progress mirrored within the paradigm of role-playing games: their activities in the classroom inform the de- velopment of their in-game avatars and unlock real-life abilities and rewards. Second, I analyse which games and aspects of gamification are conducive to the creation of a ludic space. While the use of tablets is not the core focus of this thesis, I have worked with pedagogical and language-learning games designed for tablets as well as classroom games designed to use tablets as one of their central features. -

DESIGN-DRIVEN APPROACHES TOWARD MORE EXPRESSIVE STORYGAMES a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Satisfaction of the Requirements for the Degree Of

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA SANTA CRUZ CHANGEFUL TALES: DESIGN-DRIVEN APPROACHES TOWARD MORE EXPRESSIVE STORYGAMES A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in COMPUTER SCIENCE by Aaron A. Reed June 2017 The Dissertation of Aaron A. Reed is approved: Noah Wardrip-Fruin, Chair Michael Mateas Michael Chemers Dean Tyrus Miller Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies Copyright c by Aaron A. Reed 2017 Table of Contents List of Figures viii List of Tables xii Abstract xiii Acknowledgments xv Introduction 1 1 Framework 15 1.1 Vocabulary . 15 1.1.1 Foundational terms . 15 1.1.2 Storygames . 18 1.1.2.1 Adventure as prototypical storygame . 19 1.1.2.2 What Isn't a Storygame? . 21 1.1.3 Expressive Input . 24 1.1.4 Why Fiction? . 27 1.2 A Framework for Storygame Discussion . 30 1.2.1 The Slipperiness of Genre . 30 1.2.2 Inputs, Events, and Actions . 31 1.2.3 Mechanics and Dynamics . 32 1.2.4 Operational Logics . 33 1.2.5 Narrative Mechanics . 34 1.2.6 Narrative Logics . 36 1.2.7 The Choice Graph: A Standard Narrative Logic . 38 2 The Adventure Game: An Existing Storygame Mode 44 2.1 Definition . 46 2.2 Eureka Stories . 56 2.3 The Adventure Triangle and its Flaws . 60 2.3.1 Instability . 65 iii 2.4 Blue Lacuna ................................. 66 2.5 Three Design Solutions . 69 2.5.1 The Witness ............................. 70 2.5.2 Firewatch ............................... 78 2.5.3 Her Story ............................... 86 2.6 A Technological Fix? . -

Can Game Companies Help America's Children?

CAN GAME COMPANIES HELP AMERICA’S CHILDREN? The Case for Engagement & VirtuallyGood4Kids™ By Wendy Lazarus Founder and Co-President with Aarti Jayaraman September 2012 About The Children’s Partnership The Children's Partnership (TCP) is a national, nonprofit organization working to ensure that all children—especially those at risk of being left behind—have the resources and opportunities they need to grow up healthy and lead productive lives. Founded in 1993, The Children's Partnership focuses particular attention on the goals of securing health coverage for every child and on ensuring that the opportunities and benefits of digital technology reach all children. Consistent with that mission, we have educated the public and policymakers about how technology can measurably improve children's health, education, safety, and opportunities for success. We work at the state and national levels to provide research, build programs, and enact policies that extend opportunity to all children and their families. Santa Monica, CA Office Washington, DC Office 1351 3rd St. Promenade 2000 P Street, NW Suite 206 Suite 330 Santa Monica, CA 90401 Washington, DC 20036 t: 310.260.1220 t: 202.429.0033 f: 310.260.1921 f: 202.429.0974 E-Mail: [email protected] Web: www.childrenspartnership.org The Children’s Partnership is a project of Tides Center. ©2012, The Children's Partnership. Permission to copy, disseminate, or otherwise use this work is normally granted as long as ownership is properly attributed to The Children's Partnership. CAN GAME -

THQ Nordic AB (Publ) Acquires Koch Media

THQ Nordic AB (publ) acquires Koch Media Investor Presentation February 14, 2018 Acquisition rationale AAA intellectual property rights Saints Row and Dead Island Long-term exclusive licence within Games for “Metro” based on books by Dmitry Glukhovsky 4 AAA titles in production including announced Metro Exodus and Dead Island 2 2 AAA studios Deep Silver Volition (Champaign, IL) and Deep Silver Dambuster Studios (Nottingham, UK) #1 Publishing partner in Europe for 50+ companies Complementary business models and entrepreneurial cultural fit Potential revenue synergy and strong platform for further acquisitions EPS accretive acquisition to THQ Nordic shareholders 2 Creating a European player of great scale Internal development studios1 7 3 10 External development studios1 18 8 26 Number of IPs1 91 15 106 Announced 12 5 17 Development projects1 Unannounced 24 9 33 Headcount (internal and external)1 462 1,181 1,643 Net sales 2017 9m, Apr-Dec SEK 426m SEK 2,548m SEK 2,933m2 Adj. EBIT 2017 9m, Apr-Dec SEK 156m SEK 296m3 SEK 505m2,3 1) December 31, 2017. 2) Pro forma. 3) Adjusted for write-downs of SEK 552m. Source: Koch Media, THQ Nordic 3 High level transaction structure THQ Nordic AB (publ) Koch Media Holding GmbH, seller (Sweden) (Germany) Purchase price EUR 91.5m 100% 100% SALEM einhundertste Koch Media GmbH, Operations Holding GmbH operative company (Austria) 100% (Austria) Pre-transaction Transaction Transaction information . Purchase price of EUR 91.5m – EUR 66m in cash paid at closing – EUR 16m in cash paid no later than August 14, 2018 – EUR 9.5m in shares paid no later than June 15, 2018 . -

The Video Game Industry an Industry Analysis, from a VC Perspective

The Video Game Industry An Industry Analysis, from a VC Perspective Nik Shah T’05 MBA Fellows Project March 11, 2005 Hanover, NH The Video Game Industry An Industry Analysis, from a VC Perspective Authors: Nik Shah • The video game industry is poised for significant growth, but [email protected] many sectors have already matured. Video games are a large and Tuck Class of 2005 growing market. However, within it, there are only selected portions that contain venture capital investment opportunities. Our analysis Charles Haigh [email protected] highlights these sectors, which are interesting for reasons including Tuck Class of 2005 significant technological change, high growth rates, new product development and lack of a clear market leader. • The opportunity lies in non-core products and services. We believe that the core hardware and game software markets are fairly mature and require intensive capital investment and strong technology knowledge for success. The best markets for investment are those that provide valuable new products and services to game developers, publishers and gamers themselves. These are the areas that will build out the industry as it undergoes significant growth. A Quick Snapshot of Our Identified Areas of Interest • Online Games and Platforms. Few online games have historically been venture funded and most are subject to the same “hit or miss” market adoption as console games, but as this segment grows, an opportunity for leading technology publishers and platforms will emerge. New developers will use these technologies to enable the faster and cheaper production of online games. The developers of new online games also present an opportunity as new methods of gameplay and game genres are explored. -

Handheld Microscope Users Guide

Handheld Microscope Users Guide www.ScopeCurriculum.com ii Handheld Microscope Users Guide Hand-Held Microscope User’s Guide Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................................................1 What is a Scope-On-A-Rope? .....................................................................................................1 Which model do you have?.........................................................................................................2 Analog vs. Digital .........................................................................................................................3 Where can I buy a SOAR? ...........................................................................................................3 NEW SCOPE-ON-A-ROPE..................................................................................................................4 Parts and Assembly of SOAR .....................................................................................................4 Connections .................................................................................................................................5 Turning It On.................................................................................................................................5 Comparing and Installing Lenses...............................................................................................6 How to Use and Capture Images with the 30X Lens.................................................................7 -

Hydrax-Manual

BCI The game "Hydrax" is a new concept in Adventure Games. It seeks to combine the best features of an Adventure Game with the action and graphics of an Arcade Game. As an adventurer you will be required to solve puzzles and riddles while exploring a vast underground world in your quest to find and defeat Hydrax. As an arcader you will use a joystick to control the hero and to fight various unfriendly creatures which inhabit the cave. The game is played in two ways, by means of the joystick, when fast action to defeat an enemy is required, and by typed commands if a more thoughtful solution is required. Pressing the space bar on the computer will freeze all action and allow you to type in a command. Commands may be single words or sentences. e.g. (i) LOOK-will tell you about the room (ii) OFFER 10 GOLD PIECES TO WITCH SOME USE.FUL COMMANDS INVENTORY - tells what you are currently carrying and how many life points you have left. SAVE GAME - saves game to disk (see note). EXITS FROM CAVERN The exits are left, right, back, front, up, and down. A cavern may have only one exit or any combination of six. All exits are normally visible on the screen except the front. The joystick can be used to walk through a left or right exit. JOYSTICK The joystick is used for walking, jumping, ducking, swimming and fighting. To fight you must carry a sword. Press fire button and direction of the joystick will point the sword. -

Changing Perceptions and Bucking

INAUGURAL ISSUE Q1-Q3 2008 LOUISIANA ECONOMIC QUARTERLY EA SpoRtS: FoRtUNE 1000 HQ LoUISIANA’S It’S IN LoUISIANA RELocAtIoN NUcLEAR RENAISSANcE inside 13 Economic Update Secretary The State Of Louisiana’s Economy 4 Around the Regions What’s Happening With 10 Haynesville Shale And Federal City Moret Momentum Louisiana 13 Companies That 12 Said ‘Yes’ To Louisiana Small Business Spotlight Loads Of Opportunity For 20 am thrilled to share with you the inaugural This issue also includes a variety of stories Southern Textile Services issue of Louisiana Economic Quarterly – a describing some of the most consequential Louisiana community Network new publication designed to provide economic developments in Louisiana today, Tools For Success 22 insights about Louisiana’s economy, as well including the Haynesville Shale in North 24 as economic development efforts being Louisiana, the Federal City project in New Industry outlook undertaken to enhance it. Orleans, an exciting small business success Taking Digital Arts 24 story in Alexandria, and the emerging digital To The Next Level 20 In this and subsequent issues, we will detail media industry that is starting to form in Baton major economic developments in Louisiana, Rouge, Lafayette, New Orleans and Shreveport/ on the cover including economic trends, major business Bossier. We also include a thought-provoking Changing Perceptions And 26 19 investments, small business success stories, interview with Jim Clinton, a national economic Bucking National Trends the evolution of traditional and emerging development leader who just came back to industry sectors, and state and local economic Alexandria to make a difference. How planning development initiatives. -

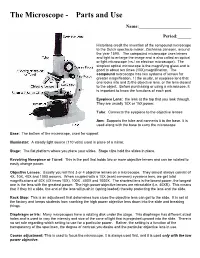

The Microscope Parts And

The Microscope Parts and Use Name:_______________________ Period:______ Historians credit the invention of the compound microscope to the Dutch spectacle maker, Zacharias Janssen, around the year 1590. The compound microscope uses lenses and light to enlarge the image and is also called an optical or light microscope (vs./ an electron microscope). The simplest optical microscope is the magnifying glass and is good to about ten times (10X) magnification. The compound microscope has two systems of lenses for greater magnification, 1) the ocular, or eyepiece lens that one looks into and 2) the objective lens, or the lens closest to the object. Before purchasing or using a microscope, it is important to know the functions of each part. Eyepiece Lens: the lens at the top that you look through. They are usually 10X or 15X power. Tube: Connects the eyepiece to the objective lenses Arm: Supports the tube and connects it to the base. It is used along with the base to carry the microscope Base: The bottom of the microscope, used for support Illuminator: A steady light source (110 volts) used in place of a mirror. Stage: The flat platform where you place your slides. Stage clips hold the slides in place. Revolving Nosepiece or Turret: This is the part that holds two or more objective lenses and can be rotated to easily change power. Objective Lenses: Usually you will find 3 or 4 objective lenses on a microscope. They almost always consist of 4X, 10X, 40X and 100X powers. When coupled with a 10X (most common) eyepiece lens, we get total magnifications of 40X (4X times 10X), 100X , 400X and 1000X. -

Chapter 11 Applications of Ore Microscopy in Mineral Technology

CHAPTER 11 APPLICATIONS OF ORE MICROSCOPY IN MINERAL TECHNOLOGY 11.1 INTRODUCTION The extraction of specific valuable minerals from their naturally occurring ores is variously termed "ore dressing," "mineral dressing," and "mineral beneficiation." For most metalliferous ores produced by mining operations, this extraction process is an important intermediatestep in the transformation of natural ore to pure metal. Although a few mined ores contain sufficient metal concentrations to require no beneficiation (e.g., some iron ores), most contain relatively small amounts of the valuable metal, from perhaps a few percent in the case ofbase metals to a few parts per million in the case ofpre cious metals. As Chapters 7, 9, and 10ofthis book have amply illustrated, the minerals containing valuable metals are commonly intergrown with eco nomically unimportant (gangue) minerals on a microscopic scale. It is important to note that the grain size of the ore and associated gangue minerals can also have a dramatic, and sometimes even limiting, effect on ore beneficiation. Figure 11.1 illustrates two rich base-metal ores, only one of which (11.1b) has been profitably extracted and processed. The McArthur River Deposit (Figure I 1.1 a) is large (>200 million tons) and rich (>9% Zn), but it contains much ore that is so fine grained that conventional processing cannot effectively separate the ore and gangue minerals. Consequently, the deposit remains unmined until some other technology is available that would make processing profitable. In contrast, the Ruttan Mine sample (Fig. 11.1 b), which has undergone metamorphism, is relativelycoarsegrained and is easily and economically separated into high-quality concentrates. -

Science for Energy Technology: Strengthening the Link Between Basic Research and Industry

ďŽƵƚƚŚĞĞƉĂƌƚŵĞŶƚŽĨŶĞƌŐLJ͛ƐĂƐŝĐŶĞƌŐLJ^ĐŝĞŶĐĞƐWƌŽŐƌĂŵ ĂƐŝĐŶĞƌŐLJ^ĐŝĞŶĐĞƐ;^ͿƐƵƉƉŽƌƚƐĨƵŶĚĂŵĞŶƚĂůƌĞƐĞĂƌĐŚƚŽƵŶĚĞƌƐƚĂŶĚ͕ƉƌĞĚŝĐƚ͕ĂŶĚƵůƟŵĂƚĞůLJĐŽŶƚƌŽů ŵĂƩĞƌĂŶĚĞŶĞƌŐLJĂƚƚŚĞĞůĞĐƚƌŽŶŝĐ͕ĂƚŽŵŝĐ͕ĂŶĚŵŽůĞĐƵůĂƌůĞǀĞůƐ͘dŚŝƐƌĞƐĞĂƌĐŚƉƌŽǀŝĚĞƐƚŚĞĨŽƵŶĚĂƟŽŶƐ ĨŽƌŶĞǁĞŶĞƌŐLJƚĞĐŚŶŽůŽŐŝĞƐĂŶĚƐƵƉƉŽƌƚƐKŵŝƐƐŝŽŶƐŝŶĞŶĞƌŐLJ͕ĞŶǀŝƌŽŶŵĞŶƚ͕ĂŶĚŶĂƟŽŶĂůƐĞĐƵƌŝƚLJ͘dŚĞ ^ƉƌŽŐƌĂŵĂůƐŽƉůĂŶƐ͕ĐŽŶƐƚƌƵĐƚƐ͕ĂŶĚŽƉĞƌĂƚĞƐŵĂũŽƌƐĐŝĞŶƟĮĐƵƐĞƌĨĂĐŝůŝƟĞƐƚŽƐĞƌǀĞƌĞƐĞĂƌĐŚĞƌƐĨƌŽŵ ƵŶŝǀĞƌƐŝƟĞƐ͕ŶĂƟŽŶĂůůĂďŽƌĂƚŽƌŝĞƐ͕ĂŶĚƉƌŝǀĂƚĞŝŶƐƟƚƵƟŽŶƐ͘ ďŽƵƚƚŚĞ͞ĂƐŝĐZĞƐĞĂƌĐŚEĞĞĚƐ͟ZĞƉŽƌƚ^ĞƌŝĞƐ KǀĞƌƚŚĞƉĂƐƚĞŝŐŚƚLJĞĂƌƐ͕ƚŚĞĂƐŝĐŶĞƌŐLJ^ĐŝĞŶĐĞƐĚǀŝƐŽƌLJŽŵŵŝƩĞĞ;^ͿĂŶĚ^ŚĂǀĞĞŶŐĂŐĞĚ ƚŚŽƵƐĂŶĚƐŽĨƐĐŝĞŶƟƐƚƐĨƌŽŵĂĐĂĚĞŵŝĂ͕ŶĂƟŽŶĂůůĂďŽƌĂƚŽƌŝĞƐ͕ĂŶĚŝŶĚƵƐƚƌLJĨƌŽŵĂƌŽƵŶĚƚŚĞǁŽƌůĚƚŽƐƚƵĚLJ ƚŚĞĐƵƌƌĞŶƚƐƚĂƚƵƐ͕ůŝŵŝƟŶŐĨĂĐƚŽƌƐ͕ĂŶĚƐƉĞĐŝĮĐĨƵŶĚĂŵĞŶƚĂůƐĐŝĞŶƟĮĐďŽƩůĞŶĞĐŬƐďůŽĐŬŝŶŐƚŚĞǁŝĚĞƐƉƌĞĂĚ ŝŵƉůĞŵĞŶƚĂƟŽŶŽĨĂůƚĞƌŶĂƚĞĞŶĞƌŐLJƚĞĐŚŶŽůŽŐŝĞƐ͘dŚĞƌĞƉŽƌƚƐĨƌŽŵƚŚĞĨŽƵŶĚĂƟŽŶĂůĂƐŝĐZĞƐĞĂƌĐŚEĞĞĚƐƚŽ ƐƐƵƌĞĂ^ĞĐƵƌĞŶĞƌŐLJ&ƵƚƵƌĞǁŽƌŬƐŚŽƉ͕ƚŚĞĨŽůůŽǁŝŶŐƚĞŶ͞ĂƐŝĐZĞƐĞĂƌĐŚEĞĞĚƐ͟ǁŽƌŬƐŚŽƉƐ͕ƚŚĞƉĂŶĞůŽŶ 'ƌĂŶĚŚĂůůĞŶŐĞƐĐŝĞŶĐĞ͕ĂŶĚƚŚĞƐƵŵŵĂƌLJƌĞƉŽƌƚEĞǁ^ĐŝĞŶĐĞĨŽƌĂ^ĞĐƵƌĞĂŶĚ^ƵƐƚĂŝŶĂďůĞŶĞƌŐLJ&ƵƚƵƌĞ ĚĞƚĂŝůƚŚĞŬĞLJďĂƐŝĐƌĞƐĞĂƌĐŚŶĞĞĚĞĚƚŽĐƌĞĂƚĞƐƵƐƚĂŝŶĂďůĞ͕ůŽǁĐĂƌďŽŶĞŶĞƌŐLJƚĞĐŚŶŽůŽŐŝĞƐŽĨƚŚĞĨƵƚƵƌĞ͘dŚĞƐĞ ƌĞƉŽƌƚƐŚĂǀĞďĞĐŽŵĞƐƚĂŶĚĂƌĚƌĞĨĞƌĞŶĐĞƐŝŶƚŚĞƐĐŝĞŶƟĮĐĐŽŵŵƵŶŝƚLJĂŶĚŚĂǀĞŚĞůƉĞĚƐŚĂƉĞƚŚĞƐƚƌĂƚĞŐŝĐ ĚŝƌĞĐƟŽŶƐŽĨƚŚĞ^ͲĨƵŶĚĞĚƉƌŽŐƌĂŵƐ͘;ŚƩƉ͗ͬͬǁǁǁ͘ƐĐ͘ĚŽĞ͘ŐŽǀͬďĞƐͬƌĞƉŽƌƚƐͬůŝƐƚ͘ŚƚŵůͿ ϭ ^ĐŝĞŶĐĞĨŽƌŶĞƌŐLJdĞĐŚŶŽůŽŐLJ͗^ƚƌĞŶŐƚŚĞŶŝŶŐƚŚĞ>ŝŶŬďĞƚǁĞĞŶĂƐŝĐZĞƐĞĂƌĐŚĂŶĚ/ŶĚƵƐƚƌLJ Ϯ EĞǁ^ĐŝĞŶĐĞĨŽƌĂ^ĞĐƵƌĞĂŶĚ^ƵƐƚĂŝŶĂďůĞŶĞƌŐLJ&ƵƚƵƌĞ ϯ ŝƌĞĐƟŶŐDĂƩĞƌĂŶĚŶĞƌŐLJ͗&ŝǀĞŚĂůůĞŶŐĞƐĨŽƌ^ĐŝĞŶĐĞĂŶĚƚŚĞ/ŵĂŐŝŶĂƟŽŶ ϰ ĂƐŝĐZĞƐĞĂƌĐŚEĞĞĚƐĨŽƌDĂƚĞƌŝĂůƐƵŶĚĞƌdžƚƌĞŵĞŶǀŝƌŽŶŵĞŶƚƐ ϱ ĂƐŝĐZĞƐĞĂƌĐŚEĞĞĚƐ͗ĂƚĂůLJƐŝƐĨŽƌŶĞƌŐLJ -

Microscope Innovation Issue Fall 2020

Masks • COVID-19 Testing • PAPR Fall 2020 CHIhealth.com The Innovation Issue “Armor” invention protects test providers 3D printing boosts PPE supplies CHI Health Physician Journal WHAT’S INSIDE Vol. 4, Issue 1 – Fall 2020 microscope is a journal published by CHI Health Marketing and Communications. Content from the journal may be found at CHIhealth.com/microscope. SUPPORTING COMMUNITIES Marketing and Communications Tina Ames Division Vice President Making High-Quality Masks 2 for the Masses Public Relations Mary Williams CHI Health took a proactive approach to protecting the community by Division Director creating and handing out thousands of reusable facemasks which were tested to ensure they were just as effective after being washed. Editorial Team Sonja Carberry Editor TACKLING CHALLENGES Julie Lingbloom Graphic Designer 3D Printing Team Helps Keep Taylor Barth Writer/Associate Editor 4 PAPRs in Use Jami Crawford Writer/Associate Editor When parts of Powered Air Purifying Respirators (PAPRS) were breaking, Anissa Paitz and reordering proved nearly impossible, a team of creators stepped in with a Writer/Associate Editor workable prototype that could be easily produced. Photography SHARING RESOURCES Andrew Jackson Grassroots Effort Helps Shield 6 Nebraska from COVID-19 About CHI Health When community group PPE for NE decided to make face shields for health care providers, CHI Health supplied 12,000 PVC sheets for shields and CHI Health is a regional health network headquartered in Omaha, Nebraska. The 119 kg of filament to support their efforts. combined organization consists of 14 hospitals, two stand-alone behavioral health facilities, more than 150 employed physician ADVANCING CAPABILITIES practice locations and more than 12,000 employees in Nebraska and southwestern Iowa.