From Space to Location Moinak Biswas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Visva-Bharati, Santiniketan Title Accno Language Author / Script Folios DVD Remarks

www.ignca.gov.in Visva-Bharati, Santiniketan Title AccNo Language Author / Script Folios DVD Remarks CF, All letters to A 1 Bengali Many Others 75 RBVB_042 Rabindranath Tagore Vol-A, Corrected, English tr. A Flight of Wild Geese 66 English Typed 112 RBVB_006 By K.C. Sen A Flight of Wild Geese 338 English Typed 107 RBVB_024 Vol-A A poems by Dwijendranath to Satyendranath and Dwijendranath Jyotirindranath while 431(B) Bengali Tagore and 118 RBVB_033 Vol-A, presenting a copy of Printed Swapnaprayana to them A poems in English ('This 397(xiv Rabindranath English 1 RBVB_029 Vol-A, great utterance...') ) Tagore A song from Tapati and Rabindranath 397(ix) Bengali 1.5 RBVB_029 Vol-A, stage directions Tagore A. Perumal Collection 214 English A. Perumal ? 102 RBVB_101 CF, All letters to AA 83 Bengali Many others 14 RBVB_043 Rabindranath Tagore Aakas Pradeep 466 Bengali Rabindranath 61 RBVB_036 Vol-A, Tagore and 1 www.ignca.gov.in Visva-Bharati, Santiniketan Title AccNo Language Author / Script Folios DVD Remarks Sudhir Chandra Kar Aakas Pradeep, Chitra- Bichitra, Nabajatak, Sudhir Vol-A, corrected by 263 Bengali 40 RBVB_018 Parisesh, Prahasinee, Chandra Kar Rabindranath Tagore Sanai, and others Indira Devi Bengali & Choudhurani, Aamar Katha 409 73 RBVB_029 Vol-A, English Unknown, & printed Indira Devi Aanarkali 401(A) Bengali Choudhurani 37 RBVB_029 Vol-A, & Unknown Indira Devi Aanarkali 401(B) Bengali Choudhurani 72 RBVB_029 Vol-A, & Unknown Aarogya, Geetabitan, 262 Bengali Sudhir 72 RBVB_018 Vol-A, corrected by Chhelebele-fef. Rabindra- Chandra -

Elective English - III DENG202

Elective English - III DENG202 ELECTIVE ENGLISH—III Copyright © 2014, Shraddha Singh All rights reserved Produced & Printed by EXCEL BOOKS PRIVATE LIMITED A-45, Naraina, Phase-I, New Delhi-110028 for Lovely Professional University Phagwara SYLLABUS Elective English—III Objectives: To introduce the student to the development and growth of various trends and movements in England and its society. To make students analyze poems critically. To improve students' knowledge of literary terminology. Sr. Content No. 1 The Linguist by Geetashree Chatterjee 2 A Dream within a Dream by Edgar Allan Poe 3 Chitra by Rabindranath Tagore 4 Ode to the West Wind by P.B.Shelly. The Vendor of Sweets by R.K. Narayan 5 How Much Land does a Man Need by Leo Tolstoy 6 The Agony of Win by Malavika Roy Singh 7 Love Lives Beyond the Tomb by John Clare. The Traveller’s story of a Terribly Strange Bed by Wilkie Collins 8 Beggarly Heart by Rabindranath Tagore 9 Next Sunday by R.K. Narayan 10 A Lickpenny Lover by O’ Henry CONTENTS Unit 1: The Linguist by Geetashree Chatterjee 1 Unit 2: A Dream within a Dream by Edgar Allan Poe 7 Unit 3: Chitra by Rabindranath Tagore 21 Unit 4: Ode to the West Wind by P B Shelley 34 Unit 5: The Vendor of Sweets by R K Narayan 52 Unit 6: How Much Land does a Man Need by Leo Tolstoy 71 Unit 7: The Agony of Win by Malavika Roy Singh 84 Unit 8: Love Lives beyond the Tomb by John Clare 90 Unit 9: The Traveller's Story of a Terribly Strange Bed by Wilkie Collins 104 Unit 10: Beggarly Heart by Rabindranath Tagore 123 Unit 11: Next Sunday by -

Deliverance of Women and Rabindranath Tagore: in Vista of Education Dr

International Journal of Research in Arts and Science, Vol. 1, No. 2, August 2015 6 Deliverance of Women and Rabindranath Tagore: In Vista of Education Dr. Tapas Pal and Dr. Sanat Kumar Rath Abstract--- Gurudevas role in the liberation of women was states in no uncertain terms that there should be equality in a determining one. He uncovered the dilemma of women and education. “Whatever is worth knowing is knowledge. It argued for their independence through his letters, short should be known equally by men and women not for the sake stories, and essays. Through his novels, he was able to of practical utility, but for the sake of knowing the desire to construct new and vital female role models to motivate a new know is the law of human nature.(Shiksha, vol.1). generation of Bengali women. Later, by his act of admitting Extra-curricular Activities such as the 1910 Drama Lakshmir females into his Santiniketan Ashram education, he became an Puja innovative pioneer in coeducation. As Santiniketan expanded to include women as students Keywords--- Liberation of Women, Ashram Education and village welfare as objectives, curriculum innovations were required. These often took place through extra-curricular activities such as the 1910 drama Lakshmir puja, which was I. INTRODUCTION staged and performed by female students. Tagore brought in dance teacher from Banaras to train the girls and when they URUDEVA’S role in the liberation of women was a left, he personally taught them. Gdetermining one. He uncovered the dilemma of women and argued for their independence through his letters, short ‘Nari-Bhavana’ stories, and essays. -

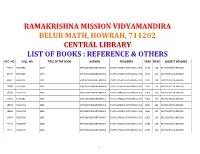

Ramakrishna Mission Vidyamandira Belur Math, Howrah, 711202 Central Library List of Books : Reference & Others Acc

RAMAKRISHNA MISSION VIDYAMANDIRA BELUR MATH, HOWRAH, 711202 CENTRAL LIBRARY LIST OF BOOKS : REFERENCE & OTHERS ACC. NO. CALL. NO. TITLE OF THE BOOK AUTHOR PUBLISHER YEAR PRICE SUBJECT HEADING 44638 R032/ENC 1978 ENYCOLPAEDIA BRITANNICA ENCYCLOPAEDIA BRITANNICA, ING 1978 150 ENCYCLOPEDIA-ENGLISH 44639 R032/ENC 1979 ENYCOLPAEDIA BRITANNICA ENCYCLOPAEDIA BRITANNICA, ING 1979 100 ENCYCLOPEDIA-ENGLISH 44641 R-032/BRI 1981 ENYCOLPAEDIA BRITANNICA ENCYCLOPEADIA BRITANNICA, INC 1981 100 ENCYCLOPEDIA-ENGLISH 15648 R-032/BRI 1982 ENYCOLPAEDIA BRITANNICA ENCYCLOPAEDIA BRITANNICA, ING 1982 100 ENCYCLOPEDIA-ENGLISH 15649 R-032/ENC 1983 ENYCOLPAEDIA BRITANNICA ENCYCLOPAEDIA BRITANNICA, ING 1983 100 ENCYCLOPEDIA-ENGLISH 17913 R032/ENC 1984 ENYCOLPAEDIA BRITANNICA ENCYCLOPAEDIA BRITANNICA, ING 1984 350 ENCYCLOPEDIA-ENGLISH 18648 R-032/ENC 1985 ENYCOLPAEDIA BRITANNICA ENCYCLOPAEDIA BRITANNICA, ING 1985 100 ENCYCLOPEDIA-ENGLISH 18786 R-032/ENC 1986 ENYCOLPAEDIA BRITANNICA ENCYCLOPAEDIA BRITANNICA, ING 1986 100 ENCYCLOPEDIA-ENGLISH 19693 R-032/ENC 1987 ENYCOLPAEDIA BRITANNICA ENCYCLOPEADIA BRITANNICA, INC 1987 100 ENCYCLOPEDIA-ENGLISH 21140 R-032/ENC 1988 ENYCOLPAEDIA BRITANNICA ENCYCLOPEADIA BRITANNICA, INC 1988 100 ENCYCLOPEDIA-ENGLISH 21141 R-032/ENC 1989 ENYCOLPAEDIA BRITANNICA ENCYCLOPEADIA BRITANNICA, INC 1989 100 ENCYCLOPEDIA-ENGLISH 1 ACC. NO. CALL. NO. TITLE OF THE BOOK AUTHOR PUBLISHER YEAR PRICE SUBJECT HEADING 21426 R-032/ENC 1990 ENYCOLPAEDIA BRITANNICA ENCYCLOPAEDIA BRITANNICA, ING 1990 150 ENCYCLOPEDIA-ENGLISH 21797 R-032/ENC 1991 ENYCOLPAEDIA -

Biography of Sarojini Naidu Saroji Naidu Also Known by the Sobriquet the Nightingale of India, Was a Child Prodigy, Indian Indep

Biography of Sarojini Naidu Saroji Naidu also known by the sobriquet The Nightingale of India, was a child prodigy, Indian independence activist and poet. Naidu was the first Indian woman to become the President of the Indian National Congress and the first woman to become the Governor of Uttar Pradesh state. was a great patriot, politician, orator and administrator. of all the famous women of India, Mrs. Sarojinidevi Naidu's name is at the top. Not only that, but she was truly one of the jewels of the world. Being one of the most famous heroines of the 20th century, her birthday is celebrated as "Women's Day" Early Life She was born in Hyderabad. Sarojini Chattopadhyay, later Naidu belonged to a Bengali family of Kulin Brahmins. But her father, Agorenath Chattopadhyay, after receiving a doctor of science degree from Edinburgh University, settled in Hyderabad State, where he founded and administered the Hyderabad College, which later became the Nizam's College in Hyderabad. Sarojini Naidu's mother Barada Sundari Devi was a poetess baji and used to write poetry in Bengali. Sarojini Naidu was the eldest among the eight siblings. One of her brothers Birendranath was a revolutionary and her other brother Harindranath was a poet, dramatist, and actor. Sarojini Naidu was a brilliant student. She was proficient in Urdu, Telugu, English, Bengali, and Persian. At the age of twelve, Sarojini Naidu attained national fame when she topped the matriculation examination at Madras University. Her father wanted her to become a mathematician or scientist but Sarojini Naidu was interested in poetry. -

Rabindranath Tagore - Poems

Classic Poetry Series Rabindranath Tagore - poems - Publication Date: 2012 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive Rabindranath Tagore(7 May 1861 – 7 August 1941) Rabindranath Tagore (Bengali: ??????????? ?????) sobriquet Gurudev, was a Bengali polymath who reshaped his region's literature and music. Author of Gitanjali and its "profoundly sensitive, fresh and beautiful verse", he became the first non-European to win the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1913. In translation his poetry was viewed as spiritual and mercurial; his seemingly mesmeric personality, flowing hair, and other-worldly dress earned him a prophet-like reputation in the West. His "elegant prose and magical poetry" remain largely unknown outside Bengal. Tagore introduced new prose and verse forms and the use of colloquial language into Bengali literature, thereby freeing it from traditional models based on classical Sanskrit. He was highly influential in introducing the best of Indian culture to the West and vice versa, and he is generally regarded as the outstanding creative artist of modern India. A Pirali Brahmin from Calcutta, Tagore wrote poetry as an eight-year-old. At age sixteen, he released his first substantial poems under the pseudonym Bhanusi?ha ("Sun Lion"), which were seized upon by literary authorities as long-lost classics. He graduated to his first short stories and dramas—and the aegis of his birth name—by 1877. As a humanist, universalist internationalist, and strident anti- nationalist he denounced the Raj and advocated independence from Britain. As an exponent of the Bengal Renaissance, he advanced a vast canon that comprised paintings, sketches and doodles, hundreds of texts, and some two thousand songs; his legacy endures also in the institution he founded, Visva- Bharati University Tagore modernised Bengali art by spurning rigid classical forms and resisting linguistic strictures. -

Tagore Studies

TAGORE STUDIES PREAMBLE Tagore Studies will be a mainly Activity, Presentation and Seminar-based Learner-Centric Course that will offer the option of taking it up as a Minor Discipline (all six courses for 18 Credits) or One-at-a-time Course (3 Credits) under Open Elective Choice where the participants would be able to engage themselves in Making a Choice, as to which Course/Courses to opt for (for instance, someone from Fine Arts and Aesthetics background may like to opt for ‗Tagore as a Culture Icon with special reference to his Painting‘ or ‗Tagore and Mass Media,‘ whereas a Literature candidate may like to go for ‗Tagore as a Poet‘ and ‗Tagore as a Fiction Writer.‘ Students enrolled in Mass Media and Communication may love to get connected to ‗Tagore and Mass Media‘ as well as ‗Tagore as a Fiction Writer.‘ Those from the History orientation may like to opt for the ‗Cultural History‘ area under ‗Tagore as a Cultural Icon‘ module). Collaboration within or across disciplines to create a joint appraisal/critique/text which could then be presented before the class for internal evaluation – by the faculty and remaining students together – in a peer review mode together.) Communication would be tested on the oral or ppt presentations that a participant may like to make on any aspect of Tagore in a Colloquium model where one person communicates and the others on the panel comment, agree, differ or substantiate etc where their performance is evaluated. Critical thinking with respect to the issues raised by Tagore in the areas on Religion, Societal Practices, Nation Building, or Politics (especially in ENG2652) on which a participant may like to write an end-semester Term Paper. -

Educational Thoughts of Rabindranath Tagore's and It's Relevance In

© 2019 JETIR March 2019, Volume 6, Issue 3 www.jetir.org (ISSN-2349-5162) EDUCATIONAL THOUGHTS OF RABINDRANATH TAGORE’S AND IT’S RELEVANCE IN PRESENT EDUCATION Prosanta Kumar Mondal Research Scholar Department of Education,University of Kalyani Kalyani, Nadia,West-Bengal Abstract: Geniuses are born. But the flowering of the multifaceted personality of Rabindranath Tagore was the result of interaction of a variety of favorable environmental factors in producing the genius. The contribution of Rabindranath Tagore in this respect as well as in other fields, especially in education, has been paramount. Rabindranath Tagore, one of the epoch-making figures of the twentieth century, is one of the most widely acclaimed wordsmiths of India. Often hailed as Gurudev or the poet of poets, Tagore, through the sheer brilliance of his narratives and incommensurable poetic flair, laid an ineffaceable impression on the minds of his readers. He was not just a mere poet or writer; he was the harbinger of an era of literature which elevated him to the stature of the cultural ambassador of India. Even today, decades after his death, this saint- like man, lives through his works in the hearts of the people of Bengal who are forever indebted to him for enriching their heritage. He was the most admired Indian writer who introduced India’s rich cultural heritage to the West and was the first non-European to be bestowed the prestigious Nobel Prize. Rabindranath Tagore’s educational model has a unique sensitivity and aptness for education within multi-racial, multi-lingual and multi-cultural situations, amidst conditions of acknowledged economic discrepancy and political imbalance. -

List of National Ngos Upto August-2020

List of National NGOs Upto August-2020 Sl.no Name of NGOs Address Reg. No. Reg. Date Renewed Valid upto District Country Remarks on 1 A Shelter for Helpless Ill House-52, Road-3/A, 1067 26-Aug-96 26-Aug-16 26-Aug-21 Dhaka Bangladesh Children (ASHIC) Dhanmondi, R/A, Dhaka Phone :9673982 www.ashic.org 2 A.B. Foundation Vill., Post + Upazilla: 2024 05-Apr-05 05-Apr-15 05-Apr-20 Dinajpur Bangladesh Chirirbandar, Dist: Dinajpur Phone: 01711-530611 3 A.M. Foster Care House-38, Road-04, Sector--05, 2397 22-Dec-08 22-Dec-13 22-Dec-18 Dhaka Bangladesh Uttara Model Town, Dhaka- 1230. Phone: 01715-475282 4 Abalamban Pachimpara, Post: Gaibandha, 2326 27-Mar-08 27-Mar-18 27-Mar-28 Gaibandha Bangladesh Upazilla: Gaibandha Sadar, Dist.: Gaibandha. Phone: 0541-62388 5 Abdul Halim Khan 1257, Khorompatty, 3123 19-Dec-17 19-Dec-27 Kishorganj Bangladesh Foundation Post+Upazila: Sadar, Kishoreganj, Tel: 01711681660 6 Abdul Momen Khan 5 Momenbagh, Dhaka-1217 0780 04-Dec-93 04-Dec-18 04-Dec-28 Dhaka Bangladesh Memorial Foundation (Khan Phone : 9330323 Foundation) 7 Abdur Rashid Khan Thakur Chapailghat Road, UZ+Zila: 2229 05-Aug-07 08-May-17 08-May-27 Gopalganj Bangladesh Foundation gopalganj-8100 Phone: 8034489, 01911-352919 www.arktf.org 8 Abed Satter Pathen 118 Isdair, Fatullah, 2842 03-Dec-13 03-Dec-18 03-Dec-28 Narayanganj Bangladesh Foundation Narayanganj Phone: 0190-251515 9 Abeda Mannan Foundation Vill: Chulash, Post Office: 2582 15-Jun-10 15-Jun-15 15-Jun-20 Dhaka Bangladesh (AMF) Maricha, Upazilla: Debidwar, Dist: Comilla. -

Rabindranath Tagore

Rabindranath Tagore 1. When was Rabindranath Tagore born? A. 7th May 1861 B. 8th May 1861 C. 9th May 1861 D. 10th May 1861 2. What is the name of Rabindranath Tagore's father? A. Abanindranath Tagore B. Dwarkanath Tagore C. Devendranath Tagore D. Bishwanath Tagore 3. What is the name of Rabindranath Tagore's mother? A. Bhubaneswari Devi B. Sarada Devi C. Bhagwati Devi D. Prabhavati Devi 4. What is the name of Rabindranath Tagore's eldest brother? A. Dwijendranath Tagore B. Gyanendra Nath Tagore C. Satyendranath Tagore D. Hemendranath Tagore 5. What is the name of Rabindranath Tagore's brother who is the first Indian to pass the ICS exam? A. Jyotirindranath Tagore B. Virendra Tagore C. Satyendranath Tagore D. Gyanendranath Tagore 6. At what age did Rabindranath Tagore start writing poetry? A. 6 years B. 7 years C. 8 years D. 9 years 7. Rabindranath Tagore started writing poetry under which pseudonym? A. Bhanu Singha B. Dikshunya Bhattacharya C. Aprakat Chandra Bhaskar D. Navin Kishore Sharman 8. What is the name of the first Nobel laureate in Asia? A. Chen Ning Young B. Hideki Yukawa C. Chandrasekhar Venkat Raman D. Rabindranath Tagore 9. In which year did Rabindranath Tagore win the Nobel Prize? A. 1909 B. 1911 C. 1913 D. 1915 10. Rabindranath Tagore won the Nobel Prize for which book? A. Chokher Bali B. Gitanjali C. Nouka Dubi D. Dena Paona 11. What is the name of the first short story of Rabindranath Tagore? A. Karuna B. Khokababur Pratyabartan C. Post Master D. Bhikarini 12. Which novel is not written by Rabindranath Tagore? A. -

Rabindranath Tagore's Novels

International Journal of English Research International Journal of English Research ISSN: 2455-2186; Impact Factor: RJIF 5.32 www.englishjournals.com Volume 3; Issue 4; July 2017; Page No. 100-103 Rabindranath Tagore’s novels: A study of man- woman relationships Mithlesh Assistant Professor, Department of English, Adarsh College Bhiwani, Haryana, India Abstract Rabindranath Tagore’s novels reflected man and woman crushed under the yoke of foreign imperialism and poised on the threshold of the modern age. The India of Tagore was grappling with political subjugation and colonial modernity. The British rule ushered in an era of bourgeois capitalism and bourgeois culture. This resulted in altering the equations between the home and the world. The ‘inner-outer’ dichotomy, was transformed into a new binary- the home and the world- the world representing the external and material, while the home symbolized one’s true spiritual identity and the internal. The woman embodied the values of a nation and acted as a repository of its heritage and culture, while at the same time, was a pivot around which the entire family revolved. Keywords: reflected, imperialism, subjugation, modernity 1. Introduction nationalism has been particularly fought on the issue of Rabindranath Tagore’s novels reflected man and woman ‘reforming women’. Numerous laws empowering women crushed under the yoke of foreign imperialism and poised have come into practice. The Widow Remarriage Act of on the threshold of the modern age. The India of Tagore 1856 and the Right to Property Act in 1874, gave a widow a was grappling with political subjugation and colonial life interest in her husband’s share of the property, are some modernity. -

Translation in Odia: a Historical Survey

Translation in Odia: A Historical Survey Aditya Kumar Panda Abstract History of translation in Odia could be studied either by surveying the major translated works in Odia chronologically or by reflecting on the development of Odia literature through translation socioculturally and politically, although both the approaches are not mutually exclusive. Translation is central to the development of Odia literature like that of any modern Indian literature. If one goes through the history of Odia literature, one can find that the quantum of Odia literature is more through translation. This essay deals with the historical account of the translation into Odia. Keyword: History, Odia, translation, adaptation, transcreation, 1. Introduction: Every history has an oral tradition of which a complete record does not exist. Whatever is recorded becomes the part of a history. A history is never a perfect history. It is biologically impossible on the part of human beings to write a perfect history which should count for each minute of the past. Therefore, history of translation is possible, if there exists written records of translation work in a language. In this historical account, “translation proper (translation of a Source Language text to a target language with fidelity to SL form and meaning)” has not only been taken into account, but also broadly interpretation, retelling, adaptation, transcreation. 1.1. Periodization: A history can be studied by dividing it according to time or place or the medium of writing. Chronologically, History of 202 Translation Today Aditya Kumar Panda Odia translation could be classified into 5 periods. They are: A. Age of Pre-Sarala and Sarala (till 15th century) B.