Enigma Variations: an Extended Family of Machines

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Prof. Dr. Phil. Rudolfkochendörffer (21.11.1911 - 23.8.1980) Bestandsverzeichnis Aus Dem Wissenschaftsarchiv Der Universität Dortmund

Mitteilungen aus der Universitätsbibliothek Dortmund Herausgegeben von Valentin Wehefritz Nr.5 Prof. Dr. phil. RudolfKochendörffer (21.11.1911 - 23.8.1980) Bestandsverzeichnis aus dem Wissenschaftsarchiv der Universität Dortmund Mit Beiträgen von Prof. Dr. Albert Sc1uleider (Dortmund) und Prof. Dr. Hans Rohrbach (Mainz) Dortmund 1985 Dieses Dokument ist urheberrechtlich geschützt! Inhaltsverzeichnis Vorwort des Herausgebers 5 Geleitwort des Dekans des Fachbereiches Mathematik 5 Prof.Dr.phi]. Rudalf Kochendörffer, 21.11.1911 - 23.8.1980. Von Albert Schneider 7 Rudalf Kochendörffer als Forscher. Von Hans Rohrbach 15 Bestandsverzeichnis 41 Rudolf Kochendörffer als Studierender 43 Rudalf Kochendörffer als Forscher 57 Rudalf Kochendörffer als Herausgeber 69 Rudalf Kochendörffer als Referent mathematischer Literatur 83 Rudolf Kochendörffer als akade m:ischer Lehrer 87 Lehrrucher und Aufsätze 89 Vorlesungen 94 W:issenscha.ft1iche PIÜfungsarbeiten 109 Verschiedene biographische Doku mente 117 Personenregister 127 Signaturenreg:ister 129 -5 Vorwort des Hera1.lS3ebers. Nachdem die Univetsitätsb:i.bliDt:hek Dortmund 1980 das Nachlaßverzeichnis von Prof. Dr. Werner Dittmar herausgegeben hat, legt die B:ibliothek nun das Bestandsverzeichnis des wissenschaftlichen Nachlasses von Prof. Dr. Kochendörffer der Öffentlichkeit vor. Das Verzeichnis wird durch die Aufsätze von Albert Schncider und Hans Rohrbach zu einer umfassenden würdigung Rudalf Kochendörffers. Professor Kochendörffer hat durch sein hohes Ansehen in der wissenschaftlichen Welt wesentlich zur Festigung des Rufes der jungen Universität Dortmund beigetragen. Die würdigung, die diese Schrift darstellt, ist auch als Dank der Univetsität Dortmund zu verstehen, der Professor Kochendömer gebührt. Dortmund, d. 25.4.1985 Valentin Wehefritz Ltd. Bibliotheksdirektor Zum Geleit Die UniversitätsbibliDthek Dortmund unternimmt es hiermit in dankenswerter Weise, Leben und Werk unseres ehemaligen Abte:iJ.ungsmitgliedes Rudalf Kochendörffer zu dokumentieren. -

The Enigma Encryption Machine and Its Electronic Variant

The Enigma Encryption Machine and its Electronic Variant Michel Barbeau, VE3EMB What is the Enigma? possible initial settings, making the total number of initial settings in the order of 10 power 16. The The Enigma is a machine devised for encrypting initial setting, taken from a code book, indicates plain text into cipher text. The machine was which pairs of letters (if any) are switched with each invented in 1918 by the German engineer Arthur other. The initial setting is called the secret key. Scherbius who lived from 1878 to 1929. The German Navy adopted the Enigma in 1925 to secure World War II was fought from 1939 to 1945 their communications. The machine was also used between the Allies (Great Britain, Russia, the by the Nazi Germany during World War II to cipher United States, France, Poland, Canada and others) radio messages. The cipher text was transmitted in and the Germans (with the Axis). To minimize the Morse code by wireless telegraph to the destination chance of the Allies cracking their code, the where a second Enigma machine was used to Germans changed the secret key each day. decrypt the cipher text back into the original plain text. Both the encrypting and decrypting Enigma The codes used for the naval Enigmas, had machines had identical settings in order for the evocative names given by the germans. Dolphin decryption to succeed. was the main naval cipher. Oyster was the officer’s variant of Dolphin. Porpoise was used for The Enigma consists of a keyboard, a scrambling Mediterranean surface vessels and shipping in the unit, a lamp board and a plug board. -

Journal Für Die Reine Und Angewandte Mathematik

BAND 771 · FeBRUAR 2021 Journal für die reine und angewandte Mathematik (Crelles Journal) GEGRÜNDET 1826 VON August Leopold Crelle FORTGEFÜHRT VON Carl Wilhelm Borchardt ∙ Karl Weierstrass ∙ Leopold Kronecker Lazarus Fuchs ∙ Kurt Hensel ∙ Ludwig Schlesinger ∙ Helmut Hasse Hans Rohrbach ∙ Martin Kneser ∙ Peter Roquette GEGENWÄRTIG HERAUSGEGEBEN VON Tobias H. Colding, Cambridge MA ∙ Jun-Muk Hwang, Seoul Daniel Huybrechts, Bonn ∙ Rainer Weissauer, Heidelberg Geordie Williamson, Sydney JOURNAL FÜR DIE REINE UND ANGEWANDTE MATHEMATIK (CRELLES JOURNAL) GEGRÜNDET 1826 VON August Leopold Crelle FORTGEFÜHRT VON August Leopold Crelle (1826–1855) Peter Roquette (1977–1998) Carl Wilhelm Borchardt (1857–1881) Samuel J. Patterson (1982–1994) Karl Weierstrass (1881–1888) Michael Schneider (1984–1995) Leopold Kronecker (1881–1892) Simon Donaldson (1986–2004) Lazarus Fuchs (1892–1902) Karl Rubin (1994–2001) Kurt Hensel (1903–1936) Joachim Cuntz (1994–2017) Ludwig Schlesinger (1929–1933) David Masser (1995–2004) Helmut Hasse (1929–1980) Gerhard Huisken (1995–2008) Hans Rohrbach (1952–1977) Eckart Viehweg (1996–2009) Otto Forster (1977–1984) Wulf-Dieter Geyer (1998–2001) Martin Kneser (1977–1991) Yuri I. Manin (2002–2008) Willi Jäger (1977–1994) Paul Vojta (2004–2011) Horst Leptin (1977–1995) Marc Levine (2009–2012) GEGENWÄRTIG HERAUSGEGEBEN VON Tobias H. Colding Jun-Muk Hwang Daniel Huybrechts Rainer Weissauer Geordie Williamson AUSGABEDATUM DES BANDES 771 Februar 2021 CONTENTS G. Tian, G. Xu, Virtual cycles of gauged Witten equation . 1 G. Faltings, Arakelov geometry on degenerating curves . .. 65 P. Lu, J. Zhou, Ancient solutions for Andrews’ hypersurface flow . 85 S. Huang, Y. Li, B. Wang, On the regular-convexity of Ricci shrinker limit spaces . 99 T. Darvas, E. -

The the Enigma Enigma Machinemachine

TheThe EnigmaEnigma MachineMachine History of Computing December 6, 2006 Mike Koss Invention of Enigma ! Invented by Arthur Scherbius, 1918 ! Adopted by German Navy, 1926 ! Modified military version, 1930 ! Two Additional rotors added, 1938 How Enigma Works Scrambling Letters ! Each letter on the keyboard is connected to a lamp letter that depends on the wiring and position of the rotors in the machine. ! Right rotor turns before each letter. How to Use an Enigma ! Daily Setup – Secret settings distributed in code books. ! Encoding/Decoding a Message Setup: Select (3) Rotors ! We’ll use I-II-III Setup: Rotor Ring Settings ! We’ll use A-A-A (or 1-1-1). Rotor Construction Setup: Plugboard Settings ! We won’t use any for our example (6 to 10 plugs were typical). Setup: Initial Rotor Position ! We’ll use “M-I-T” (or 13-9-20). Encoding: Pick a “Message Key” ! Select a 3-letter key (or indicator) “at random” (left to the operator) for this message only. ! Say, I choose “M-C-K” (or 13-3-11 if wheels are printed with numbers rather than letters). Encoding: Transmit the Indicator ! Germans would transmit the indicator by encoding it using the initial (daily) rotor position…and they sent it TWICE to make sure it was received properly. ! E.g., I would begin my message with “MCK MCK”. ! Encoded with the daily setting, this becomes: “NWD SHE”. Encoding: Reset Rotors ! Now set our rotors do our chosen message key “M-C-K” (13-3-11). ! Type body of message: “ENIGMA REVEALED” encodes to “QMJIDO MZWZJFJR”. -

Thaumatotibia Leucotreta (Meyrick) (Lepidoptera: Tortricidae) Population Ecology in Citrus Orchards: the Influence of Orchard Age

Thaumatotibia leucotreta (Meyrick) (Lepidoptera: Tortricidae) population ecology in citrus orchards: the influence of orchard age Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY at RHODES UNIVERSITY by Sonnica Albertyn December 2017 ABSTRACT 1 Anecdotal reports in the South African citrus industry claim higher populations of false codling moth (FCM), Thaumatotibia (Cryptophlebia) leucotreta (Meyr) (Lepidoptera: Tortricidae), in orchards during the first three to five harvesting years of citrus planted in virgin soil, after which, FCM numbers seem to decrease and remain consistent. Various laboratory studies and field surveys were conducted to determine if, and why juvenile orchards (four to eight years old) experience higher FCM infestation than mature orchards (nine years and older). In laboratory trials, Washington Navel oranges and Nova Mandarins from juvenile trees were shown to be significantly more susceptible to FCM damage and significantly more attractive for oviposition in both choice and no-choice trials, than fruit from mature trees. Although fruit from juvenile Cambria Navel trees were significantly more attractive than mature orchards for oviposition, they were not more susceptible to FCM damage. In contrast, fruit from juvenile and mature Midnight Valencia orchards were equally attractive for oviposition, but fruit from juvenile trees were significantly more susceptible to FCM damage than fruit from mature trees. Artificial diets were augmented with powder from fruit from juvenile or mature Washington Navel orchards at 5%, 10%, 15% or 30%. Higher larval survival of 76%, 63%, 50% and 34%, respectively, was recorded on diets containing fruit powder from the juvenile trees than on diets containing fruit powder from the mature trees, at 69%, 57%, 44% and 27% larval survival, respectively. -

Code Breaking at Bletchley Park

Middle School Scholars’ CONTENTS Newsletter A Short History of Bletchley Park by Alex Lent Term 2020 Mapplebeck… p2-3 Alan Turing: A Profile by Sam Ramsey… Code Breaking at p4-6 Bletchley Park’s Role in World War II by Bletchley Park Harry Martin… p6-8 Review: Bletchley Park Museum by Joseph Conway… p9-10 The Women of Bletchley Park by Sammy Jarvis… p10-12 Bill Tutte: The Unsung Codebreaker by Archie Leishman… p12-14 A Very Short Introduction to Bletchley Park by Sam Corbett… p15-16 The Impact of Bletchley Park on Today’s World by Toby Pinnington… p17-18 Introduction A Beginner’s Guide to the Bombe by Luca “A gifted and distinguished boy, whose future Zurek… p19-21 career we shall watch with much interest.” This was the parting remark of Alan Turing’s Headmaster in his last school report. Little The German Equivalent of Bletchley could he have known what Turing would go on Park by Rupert Matthews… 21-22 to achieve alongside the other talented codebreakers of World War II at Bletchley Park. Covering Up Bletchley Park: Operation Our trip with the third year academic scholars Boniface by Philip Kimber… p23-25 this term explored the central role this site near Milton Keynes played in winning a war. 1 intercept stations. During the war, Bletchley A Short History of Bletchley Park Park had many cover names, which included by Alex Mapplebeck “B.P.”, “Station X” and the “Government Communications Headquarters”. The first mention of Bletchley Park in records is in the Domesday Book, where it is part of the Manor of Eaton. -

Meesters Van Het Diamant

MEESTERS VAN HET DIAMANT ERIC LAUREYS Meesters van het diamant De Belgische diamantsector tijdens het nazibewind www.lannoo.com Omslagontwerp: Studio Lannoo Omslagillustratie: Grote Zaal van de Beurs voor Diamanthandel Foto’s: Beurs voor Diamanthandel Kaarten: Dirk Billen © Uitgeverij Lannoo nv, Tielt, 2005 en Eric Laureys D/2005/45/432 – ISBN 90 209 6218 3 – NUR 688 Niets uit deze uitgave mag worden verveelvoudigd en/of openbaar gemaakt door middel van druk, fotokopie, microfilm, internet of op welke wijze ook zonder voorafgaande schriftelijke toestemming van de uitgever. Gedrukt en gebonden bij Drukkerij Lannoo nv, Tielt Inhoud Dankwoord 9 Woord vooraf 11 Terminologische afspraken en afkortingen 15 1. Inleiding tot de diamantsector 23 Economisch belang van de diamantsector 23 Diamantontginning 24 Diamantbewerking 27 2. Ontstaan en ontwikkeling van machtscentra 35 De Beers en het Zuid-Afrikaanse kartel 35 Het Londens Syndicaat 38 De Forminière en het Kongolese kartel 41 Het Antwerpse diamantcentrum 48 3. Uitbouw van het Belgische overwicht – De diamantnijverheid tijdens de Eerste Wereldoorlog en de grote crisis 65 De eerste diamantdiaspora 65 Achteruitgang van Amsterdam 70 Contract tussen de Forminière en het Londens Syndicaat 71 Rol van de diamantbanken 75 Consolidatie van De Beers 82 4. De diamantsector, de opkomst van het naziregime en de nakende oorlog 87 Corporatisme in het interbellum 87 De Duitse nieuwe economische orde 91 Naziorganisatie van de Duitse diamantexploitatie 96 België, de vooroorlogse diamantsector en de anti-Duitse boycot 115 De Nederlandse ‘verdedigingsvoorbereiding’ 134 De Britse diamantcontrole en de Schemeroorlog 135 Amerikaanse diamantcontrole op de vooravond van Pearl Harbor 142 5. De grote uitdaging – De diamantsector tijdens de Tweede Wereldoorlog 147 Opgang van het industriediamant 147 Het fiasco van Cognac 151 De tweede diamantdiaspora 163 6 De Duitse greep op de Belgische diamantsector 178 Reorganisatie van de sector in België 203 6. -

Subject Reference Dbase 09-05-2006

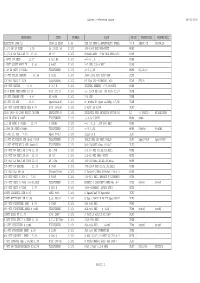

Subject reference dbase 09-05-2006 ONDERWERP TYPE NUMMER BIJZ GROEP TREFWOORD1 TREFWOORD2 ELECTRON 1958.12 1958.12 ELEC Z 46 TEK CX GEVR L,KWANTONETC KUBEL TS-N KERST CX LW,KW,LO 0,5/1 KW LW SEND 2.39 As 33/A1 34 Z 101 100-1000 KHZ MOB+FEST MOBS 0,7/1,4 KW SEND AS 60 10.40 AS 60 Z 101 FRUEHE AUSF 3-24 MHZ MOB+FEST MOBS 1 KWTT KW SEND 11.37 S 521 Bs Z 101 =+/-G 1,5.... MOBS 1 KWTT SHORT WAVE TR 5.36 S 486F Z 101 3-7 UND 2,5-6 MHZ MOBS 1 kW KW SEND S 521Bs TELEFUNKEN Z 172 +/-G 1,2K MOBS G1,2K+/- 10 WTT TELEF SENDER 10.34 S 318H Z 101 1500-3333 KHZ GUSS GEH SCHS 100 WTT SEND S 317H TELEFUNKEN Z 172 RS 31g 100-800METER alt SCHS S317H 100 WTT SENDER 4.33 S 317 H Z 101 UNIVERS SENDER 377-3000KHZ MOBS 15 W EINK SEND EMPF 10.35 Stat 272 B Z 101 +/- 15 W SE 469 SE 5285 F1/37 TRSE 15 WTT KARREN STN 4.40 SE 469A Z 101 3-5 MHZ TRSE 15 WTT KW STN 10.35 Spez804/445 Z 101 S= 804Bs E= Spez 445dBg 3-7,5M TRSE 150 WTT LANGW SENDE ANL 8.39 Stat 1006aF Z 101 S 427F SA 429F FLFU 1898-1938 40 JAAR RADIO IN NED SWIERSTRA R. Z 143 INLEGVEL VAN SWIERSTA PRIVE'38 LI 40 RADIO!! WILHELMINA 1kW KW SEND S 486F TELEFUNKEN Z 172 +/-2,5-7,5MHZ MOBS S486 1,5 LW SEND S 366Bs 11.37 S 366Bs Z 101 =+/- G1,5...100-600 KHZ MOBS 1,5kW LW SEND S366Bs TELEFUNKEN Z 172 +/-G 1,5L MOBS S366Bs S366BS 20 WTT FL STN 3.35 Spez 378mF Z 101 TELEF D B FLFU 20 WTT FLUGZEUG STN Spez 378nF TELEFUNKEN Z 172 URALT ANL LW FEST FREQU FLFU Spez378nF Spez378NF 20 WTT MITTELWELL GER Stat901 TELEFUNKEN Z 172 500-1500KHZ Stat 901A/F FLFU 200 WTT KW SEND AS 1008 11.39 AS 1008 Z 101 2,5-10 MHZ A1,A2,A3,HELL -

Enigma 2000 Newsletter

ENIGMA 2000 NEWSLETTER http://www.enigma2000.org.uk BAe Systems Type 101 Mobile Air Defence Radar System. A fully automatic system capable of firing devices without human intervention. Located in Kent Tnx Male Anon ISSUE 72 September 2012 http://www.enigma2000.org.uk 1 Editorial, Issue 72 Variable signals across the month of July; rapidly changeable weather leading to some peculiar conditions with QRN rearing its ugly head. To break this cycle we offer the cover story before our station round up. Cover pic story Olympics and the Aether Anon In case anyone is still unaware London is hosting the 2012 Olympics, in fact by the time you read this it will all be over. Among the preparations is the need to ensure sufficient radio frequencies are available to meet an unprecedented demand. As the world's media descend on East London there will be a need for a huge range of services from satellite links to mobile phones, Wi-Fi, 2-way radios, radio links and wireless microphones. The job of providing all this falls to the British regulator Ofcom. One of our members living close to London has stumbled across what may be a strange side effect of this process. As a monitor of all things radio he regularly scans the FM broadcast band, logging illegal "pirate" stations centred on the capital. For the past few years the band has been seemingly abandoned to the pirates, for Ofcom, once a proactive body, now only acts when an interference complaint is received. Many of the stations run twenty four-hours a day, seven days a week, with others adding to the mix at weekends. -

Kneser, Martin an Alan Baker Pronfelden, 2.8.1969

Niedersächsische Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek Göttingen Nachlass Martin Kneser Professor der Mathematik 21.1.1928 – 16.2.2004 Provenienz: als Geschenk aus Familienbesitz erhalten Acc. Mss. 2007.3 Acc. Mss. 2010.4/2 Göttingen 2012 Inhaltsverzeichnis Seite Allgemeine Korrespondenz 3 Signatur: Ms. M. Kneser A 1 - A 437 Berufungsangelegenheiten 85 Signatur: Cod. Ms. M. Kneser B 1 - B 153 Habilitationsverfahren 116 Signatur: Cod. Ms. M. Kneser C 1 - C 9 Vorlesungsmanuskripte 118 Signatur: Cod. Ms. M. Kneser D 1 - D 74 Vorlesungs- und Seminarausarbeitungen, überwiegend von Schülern angefertigt 129 Signatur: Cod. Ms. M. Kneser E 1 - E 23 Übungen 136 Signatur: Cod. Ms. M. Kneser F 1 - F 44 Seminare und Arbeitsgemeinschaften 143 Signatur: Cod. Ms. M. Kneser G 1 - G 8 Manuskripte 145 Signatur: Cod. Ms. M. Kneser H 1 - H 23 Sonderdrucke eigener Veröffentlichungen 153 Signatur: Cod. Ms. M. Kneser I 1 Mathematikgeschichte : Materialien zu einzelnen Personen 154 Signatur: Cod. Ms. M. Kneser J 1 - J 9 Tagungen und Vortragsreisen 158 Signatur: Cod. Ms. M . Kneser K 1 - K 8 Arbeitsgemeinschaft Oberwolfach 165 Signatur: Cod. Ms. M. Kneser L 1 - L 4 Arbeiten von Doktoranden 166 Signatur: Cod. Ms. M. Kneser M 1 - M 16 Akten und Sachkorrespondenz zu wissenschaftlichen Einrichtungen 169 Signatur: Cod. Ms. M. Kneser N 1 - N 5 Urkunden 172 Signatur: Cod. Ms. M . Kneser O 1 - O 10 Varia 174 Signatur: Cod. Ms. M. Kneser P 1 - P 5 2 Allgemeine Korrespondenz Signatur: Cod. Ms. M. Kneser A 1 - A 437 COD. MS. M. KNESER A 1 Aleksandrov, Pavel S. Briefwechsel mit Martin Kneser / Pavel S. -

Hubert A. Berens (1936–2015)

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com ScienceDirect Journal of Approximation Theory 198 (2015) iv–xxix www.elsevier.com/locate/jat In memoriam In Memoriam: Hubert A. Berens (1936–2015) Hubert Anton Berens passed away in Erlangen, Germany, on February 9, 2015. He was 78 years old. He is survived by his wife, Ursula, sons Christian & Harald and daughter Eve, and eight grandchildren. Berens was born on May 6, 1936 in Suttrop (Warstein), Germany. After receiving his Abitur in Ruthen¨ in 1957, he went to RWTH (Rheinisch-Westfalische¨ Technische Hochschule) in Aachen http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0021-9045(15)00110-0 In memoriam / Journal of Approximation Theory 198 (2015) iv–xxix v to study physics. He received his diploma in 1962 and was granted his doctorate in mathematics at RWTH in 1964. After his habilitation in 1968, Berens joined the University of California at Santa Barbara as an assistant professor. He took a leave to University of Texas at Austin to work with George Lorentz in 1970 and left his position in UCSB for UT Austin in 1972. He was appointed the Wilhelm Specht professor at the Mathematical Institute of the University of Erlangen-Nurnberg,¨ Germany, in 1973, a position he held until his retirement in 2001. He had seven Ph.D students. The author of seventy papers and two books, Berens worked in approximation theory, functional analysis and Fourier analysis. He received his doctoral degree from Paul Butzer, their book on semigroups of operators [B1] became a classic (1268 citations in Google Scholar). He wrote his habilitation thesis on interpolation methods for dealing with approximation processes in Banach spaces. -

Bletchley Park and Our Talk on Motorsport 1894 -1939

HAYES MEN’S FELLOWSHIP Newsletter April 2020, edited by Allan Evison, HMF Honorary Secretary (Membership Enquiries: For more information on joining the Fellowship retired and semi-retired men can ring me for a friendly chat on 020 8402 7416, or please drop me an e-mail to [email protected]) CORONAVIRUS EXTRA 2 KEEPING IN TOUCH: The purpose of this mid-month Newsletter is to keep in touch with members of the Fellowship at a time when we are all social distancing and many will be self isolating. The Committee want to assure members that although there is little opportunity for face to face meetings at the moment, they have not been forgotten. Your Committee are happy to chat over the phone with any of you who may be feeling isolated at this difficult time. Their numbers are on your current Membership Card. Things to do: So far we have missed out on our planned Outing to Bletchley Park and our talk on Motorsport 1894 -1939. We are hoping to reschedule these activities but until then we want to give members a taste of what has been missed/what is to come and also some things you might want to do in the meantime. So this Newsletter has:- • Things to occupy us! - we also have a quiz and a few other suggestions for things we might all do in our enforced social distancing. (Page 2) • Outing - Bletchley Park – information and photos about activities there during WW11. (Page 4) • Talk - Motor Sport 1894 -1939 – this is a broad topic and for this Newsletter we just focus on the role played by the Brooklands Motor Racing Circuit over that period.