BAME Arts Development Programme (2016 – 2019)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The VLI Is a Composite Index Based on a Range Of

OFFICIAL: This document should be used by members for partner agencies and police purposes only. If you wish to use any data from this document in external reports please request this through Birmingham Community Safety Partnership URN Date Issued CSP-SA-02 v3 11/02/2019 Customer/Issued To: Head of Community Safety, Birmingham Birmi ngham Community Safety Partnership Strategic Assessment 2019 The profile is produced and owned by West Midlands Police, and shared with our partners under statutory provisions to effectively prevent crime and disorder. The document is protectively marked at OFFICIAL but can be subject of disclosure under the Freedom of Information Act 2000 or Criminal Procedures and Investigations Act 1996. There should be no unauthorised disclosure of this document outside of an agreed readership without reference to the author or the Director of Intelligence for WMP. Crown copyright © and database rights (2019) Ordnance Survey West Midlands Police licence number 100022494 2019. Reproduced by permission of Geographers' A-Z Map Co. Ltd. © Crown Copyright 2019. All rights reserved. Licence number 100017302. 1 Page OFFICIAL OFFICIAL: This document should be used by members for partner agencies and police purposes only. If you wish to use any data from this document in external reports please request this through Birmingham Community Safety Partnership Contents Key Findings .................................................................................................................................................. 4 Reducing -

Ageing in Place Sparkbrook

AGEING IN PLACE SPARKBROOK Outline Report of the Ageing better research undertaken within the Sparkbrook Ward (pre-2018) in Birmingham The Sparkbrook Ward was one of five projects developed as part of the Ageing Better programme in Birmingham. Following the Local Authority reorganisation in the 2018 elections the Sparkbrook Ward became two wards. Sparkbrook and Balsall Heath East, and Balsall Heath West. Research and report undertaken by Ashiana Community Project supported by RnR Organisation. Mohammed Shafique, Chief Officer, Ashiana Community Project Ted Ryan Special Projects Director, RnR Organisation Contents Local Context Name of ward(s), population and information on demographics1, particularly around BAME groups 2 1 Demographics, Housing, Faith and community provision, Commercial centres Parks and green space, leisure facilities, Public transport, What might the area be known for locally? 3 1. BAME-led organisations - Engagement with older people 4 BAME-led organisations in the area – table of organisations How the organisations work with older members of their community 8 2 Changes to ways of working and why these changes have come about 9 Barriers faced when trying to engage with older people Community partnership activity 10 Working with other organisations Other partnership activity Benefits of partnership work 11 Important social infrastructure for older members of the BAME community Details of what places are important for social contacts and information 13 Types of social capital Has there been any relevant changes to this in recent years and what have the impacts been? i.e. 3 closure of community centres, libraries etc. Any differences in terms of age, gender, mobility/ disability issues, 14 Use of online platforms (social media, WhatsApp etc) Analysis and comment on types and levels of social capital References / notes 15 1 1. -

Strategic Needs Assessment

West Midlands Violence Reduction Unit STRATEGIC NEEDS ASSESSMENT APRIL 2021 westmidlands-vru.org @WestMidsVRU 1 VRU STRATEGIC NEEDS ASSESSMENT CONTENTS 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1. Executive Summary ..................................................................................................................................3 Violence has been rising in the West Midlands for several years, a trend - sadly - that has been seen across 2. Introduction and Aims .............................................................................................................................4 much of England & Wales. Serious violence, such as knife crime, has a disproportionately adverse impact on some of our most vulnerable 3. Scope and Approach ................................................................................................................................5 people and communities. All too often, it causes great trauma and costs lives, too often young ones. 4. Economic, Social and Cultural Context ...............................................................................................6 In the space of five years, knife crime has more than doubled in the West Midlands, from 1,558 incidents in the year to March 2015, to more than 3,400 in the year to March 2020, according to the Office for National Statistics. 5. The National Picture – Rising Violence ...............................................................................................8 Violence Reduction Units were set up to help prevent this rise in serious violence -

Blank Partnership Template

GREATER BIRMINGHAM AND SOLIHULL LOCAL ENTERPRISE PARTNERSHIP PLACE BOARD Tuesday 02 February 2021, 10:00-11:30 Venue: MS Teams (virtual meeting) AGENDA No. Time Presenting Subject Pre Read Purpose Owner Expected outcome • Introduction Welcome, apologies and • Intro of LBS 1 10:00 Chair Place Board introductions • Intro of SH • Registering and Disclosing interests Decisions and actions of the To agree the minutes of the last meeting Agree minutes of last 2 10:05 Chair last meeting, and matters Attached on 23.09.2020 and to note and discuss any meeting arising matters arising Christian Sayer Progress noted, and 3 10:10 / Shanaaz General LEP & Policy Update Attached General LEP update Place Board any next steps agreed Carroll Shanaaz To discuss progress so far, and to highlight Progress noted, and 4 10:20 Carroll / Whole Place Zones Attached Place Board the key points that will be any next steps agreed Christian Sayer Update on the recent call for Place / Progress noted, and 5 10:35 Sarah Hughes SEP Enabling Fund Attached Place Board Culture funding applications any next steps agreed Progress noted, and 6 10:45 Alex Taylor GBSLEP Green Recovery Verbal Overview of GBSLEP Green Recovery Place Board any next steps agreed Progress noted, and 7 10:55 Christian Sayer GBSLEP Funding Update Verbal Update on GBSLEP Funding streams Place Board any next steps agreed 1 No. Time Presenting Subject Pre Read Purpose Owner Expected outcome Update on current Place Delivery Plan and Shanaaz Place Delivery Plan Progress Progress noted, and 8 11:00 Attached -

Active Communities Pilot in Birmingham and Solihull Awarded £9.72 Million* National Lottery Grant from Sport England

PRESS RELEASE Active Communities Pilot in Birmingham and Solihull awarded £9.72 million* national lottery grant from Sport England Embargoed until release date 04/02/019 An innovative partnership involving a range of organisations across Birmingham and Solihull has secured £9.72m* of National Lottery funding from Sport England to deliver Active Communities a new vision to tackle physical inactivity in Birmingham and Solihull, reaching the population of over 450,000 people. The Active Communities partnership is being jointly led by The Active Well Being Society (TAWS) – a mutual benefit society that works to improve the lives and well-being of residents across the local area and Solihull Council. It aims to work collaboratively with local organisations, volunteers and local people to help improve the quality of life of some of the most vulnerable in the community. The Local Community Action Networks will design and lead on activities such as local festivals, with the support and guidance from a dedicated officer. Physical inactivity is the fourth leading cause of premature deaths in the UK and costs the country an estimate £7.4 billion a year. The Active Communities pilot in Birmingham and Solihull is one of 12 Sport England National Lottery funded Local Delivery Pilots, an innovative new approach to build healthier, more active communities in England and tackle the barriers in communities that stop people from getting active head on. By focusing intensively in six areas, The Active Communities team and their local partners are working with residents, looking at what stops them being active and working out ways to deal with these barriers. -

Of the Finance and Value for Money Overview and Scrutiny Commission Will Be Held at 13:00 on Friday, 17 January 2020 in Room 77

Please ask for: Fiona Harbord Telephone: 01482 613154 Fax: 01482 614804 Email: [email protected] Text phone: 01482 300349 Date: Wednesday, 08 January 2020 Dear Councillor, Finance and Value for Money Overview and Scrutiny Commission The next meeting of the Finance and Value for Money Overview and Scrutiny Commission will be held at 13:00 on Friday, 17 January 2020 in Room 77 . The Agenda for the meeting is attached and reports are enclosed where relevant. Please Note: It is likely that the public, (including the Press) will be excluded from the meeting during discussions of exempt items since they involve the possible disclosure of exempt information as describe in Schedule 12A of the Local Government Act 1972. Yours faithfully, Scrutiny Officer for the Town Clerk Town Clerk Services, Hull City Council, The Guildhall, Alfred Gelder Street, Hull, HU1 2AA www.hullcc.gov.uk Tel: 01482 300300 Page 1 of 142 Finance and VFM OSC To: Membership: Councillors Abbott, Bell, Bridges (DC), Burton, Healand, Herrera-Richmond, Matthews, Nicola (C), Ross, Singh Officers: David Bell, Director of Finance and Transformation Fiona Harbord, Scrutiny Officer (x5) Portfolio Holders: Councillor Lunn, Portfolio Holder for Adult Services and Public Health Councillor Pantelakis, Portfolio Holder for Corporate Services Councillor Webster, Portfolio Holder for Finance and Transformation For Information: Councillor Chaytor, Chair of Overview and Scrutiny Management Committee Reference Library (Public Set) Page 2 of 142 Finance and Value for Money Overview and Scrutiny Commission 13:00 on Friday, 17 January 2020 Room 77 A G E N D A PROCEDURAL ITEMS 1 Apologies To receive apologies for those Members who are unable to attend the meeting. -

Educational Outcome Dashboards Birmingham and Constituency Level

Educational Outcome Dashboards Birmingham and Constituency Level 2018 Examinations and Assessments (Revised) March 2019 Data and Intelligence Team Birmingham City Council [email protected] Primary Phase Covers Headline Measures for Early Years, Key stage 1 and Key stage 2 (revised) Constituency information relates to pupils living in the area at time of school census using their home postcode as reference. Postcodes matched to Ward and Constituency via: https://www.ons.gov.uk/methodology/geography/geographicalproducts/postcodeproducts Coverage From May 2018 some wards cross constituency boundaries. For purely comparison purposes all wards have been matched to a single constituency based on the highest proportion of children. Ward coverage indicates the amount of children in the ward within the constituency. In the case of constituency, coverage indicates the proportion of it that is made up by the displayed wards. All figures represent all children living in indicated area. 2017 / 2018 Primary phase outcomes for children attending a state school in Birmingham EYFSP Key stage 1 Key stage 1 Key stage 1 Good Level of Development Reading at least expected Writing at least expected Maths at least expected National 72% 75% 70% 76% West Midlands 69% 74% 69% 75% Stat Neighbours 69% 75% 70% 76% Core Cities 68% 72% 66% 73% Birmingham 68% 73% 67% 73% Key stage 2 Key stage 2 Reading average progress Writing average progress Maths average progress Reading, Writing & Maths (EXS+) NationalNational National National 65% West MidlandsWest -

Local Residents B Submissions to the Birmingham City Council Electoral Review

Local Residents B submissions to the Birmingham City Council electoral review This PDF document contains submissions from local residents with surnames beginning with B. Some versions of Adobe allow the viewer to move quickly between bookmarks. / !/ " # $% & 7 :''5 '3 + , +7983 From: V. K. Bahal (Synatel) [ Sent: 14 June 2016 12:59 To: reviews <[email protected]> Subject: re : Election Boundaries Commission Please note that we wish for our property, to be included in the Harborne Ward and NOT in the Quinton Ward. Mr V. K. Bahal & Mrs S K Bahal The linked image cannot be displayed. The file may have been moved, renamed, or deleted. Verify that the link points to the correct file and location. The linked image cannot be displayed. The file may have been moved, renamed, or deleted. Verify that the link points to the correct file and location. The linked image cannot be displayed. The file may have been moved, renamed, or deleted. Verify that the link points to the correct file and location. See us on: The linked image cannot be displayed. The file may have been moved, renamed, or deleted. Verify that the link points to the correct file and location. The linked image cannot be displayed. The file may have been moved, renamed, or deleted. Verify that the link points to the correct file and location. The linked image cannot be displayed. The file may have been moved, renamed, or deleted. Verify that the link points to the correct file and location. Detection & Control - in Action! Made in Great Britain Note: This e-mail (and any attachments) is/are confidential and may be privileged. -

Download: Index of Deprivation 2019

Deprivation in Birmingham Analysis of the 2019 Indices of Deprivation December 2019 Economic Policy Inclusive Growth Directorate Summary The Indices of Deprivation 2019 The Indices of Deprivation (IOD) 2019 are the Government’s official measure of deprivation for English Income Employment Education Health local authorities and neighbourhoods. The 2019 data was released in September 2019 by the Ministry for Housing (22.5%) (22.5%) (13.5%) (13.5%) Communities and Local Government (MHCLG). The IOD includes the headline Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) as well as indices covering income deprivation for young people and for older people. This report provides analysis of the 2019 findings including: • Deprivation at a city level comparing Birmingham's performance with other areas in the region and the English Core Cities. Measures the Measures the Measures the lack of Measures the risk of attainment and skills in • Birmingham’s performance in relation to the IMD sub proportion of the proportion of the premature death and domains. population working age population the local population the impediment to experiencing involuntarily excluded quality of life through • Deprivation within the city focussing on relative levels of deprivation related to from the labour market poor physical or mental deprivation at a neighbourhood and Deprivation within low income health the city focussing on relative levels of deprivation at a neighbourhood and ward level. Crime Barriers to Living The Index of Multiple Deprivation Housing & Supplementary (9.3%) Services Environment Indices The IMD is based on 39 separate indicators, organised across seven sub domains of deprivation which are (9.3%) (9.3%) Income combined and weighted to calculate the Index of Deprivation Multiple Deprivation 2019 as shown in the infographic Affecting opposite. -

Ort Gallery Impact Report 2019

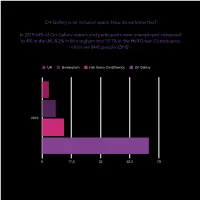

Ort Gallery is an inclusive space. How do we know this? In 2019 64% of Ort Gallery visitors and participants were unemployed compared to 4% in the UK, 8.2% in Birmingham and 13.1% in the Hall Green Constituency which are 5445 people (ONS). UK Birmingham Hall Green Constituency Ort Gallery 2019 0 17.5 35 52.5 70 "Although the ‘working class’ are 35% of the working population, they make up only 13% of publishing, 18% of music, performing and visual arts, 12% of film, TV, video, radio and photography, and 21% of museums, galleries and libraries.” Jerwood Arts Country Arts Industry Ort Gallery 50 37.5 25 12.5 0 2019 UK Art Industry Balsall Heath West Sparkbrook & Balsall Heath East Ort Gallery 2019 0 22.5 45 67.5 90 "The total percentage of the NPO workforce with a Black and Minority Ethnic background (BME) is 11%." Equality, Diversity and the Creative Case, Arts Council Non-White residents make up 14% in the UK (ONS), 65.9% in Balsall Heath West & 83.2 in Sparkbrook and Balsall Heath East. 2019 100 75 50 25 0 0 3 6 9 12 We worked with 40 artists in 2019 and we had 79 artist members. We are proud to be a talent incubator. FreeHandFanatic was part of Ikon's Forward exhibition at the Medicine Gallery, Farwa Moledina started working at Ikon and was exhibited at the Lahore Biennale in early 2020, Hira Butt had her work shown at the New Art West Midlands showcase in Coventry and Karen McLean announced a show at Walsall Art Gallery in 2020. -

Details of Unclaimed Deposits / Inoperative Accounts

CITIBANK We refer to Reserve Bank of India’s circular RBI/2014-15/442 DBR.No.DEA Fund Cell.BC.67/30.01.002/2014-15. As per these guidelines, banks are required to display the list of unclaimed deposits/inoperative accounts which are inactive/ inoperative for ten years or more on their respective websites. This is with a view of enabling the public to search the list of account holders by the name of: Account Holder/Signatory Name Address HASMUKH HARILAL 207 WISDEN ROAD STEVENAGE HERTFORDSHIRE ENGLAND UNITED CHUDASAMA KINGDOM SG15NP RENUKA HASMUKH 207 WISDEN ROAD STEVENAGE HERTFORDSHIRE ENGLAND UNITED CHUDASAMA KINGDOM SG15NP GAUTAM CHAKRAVARTTY 45 PARK LANE WESTPORT CT.06880 USA UNITED STATES 000000 VAIDEHI MAJMUNDAR 1109 CITY LIGHTS DR ALISO VIEJO CA 92656 USA UNITED STATES 92656 PRODUCT CONTROL UNIT CITIBANK P O BOX 548 MANAMA BAHRAIN KRISHNA GUDDETI BAHRAIN CHINNA KONDAPPANAIDU DOOR NO: 3/1240/1, NAGENDRA NAGAR,SETTYGUNTA ROAD, NELLORE, AMBATI ANDHRA PRADESH INDIA INDIA 524002 DOOR NO: 3/1240/1, NAGENDRA NAGAR,SETTYGUNTA ROAD, NELLORE, NARESH AMBATI ANDHRA PRADESH INDIA INDIA 524002 FLAT 1-D,KENWITH GARDENS, NO 5/12,MC'NICHOLS ROAD, SHARANYA PATTABI CHETPET,CHENNAI TAMILNADU INDIA INDIA 600031 FLAT 1-D,KENWITH GARDENS, NO 5/12,MC'NICHOLS ROAD, C D PATTABI . CHETPET,CHENNAI TAMILNADU INDIA INDIA 600031 ALKA JAIN 4303 ST.JACQUES MONTREAL QUEBEC CANADA CANADA H4C 1J7 ARUN K JAIN 4303 ST.JACQUES MONTREAL QUEBEC CANADA CANADA H4C 1J7 IBRAHIM KHAN PATHAN AL KAZMI GROUP P O BOX 403 SAFAT KUWAIT KUWAIT 13005 SAJEDAKHATUN IBRAHIM PATHAN AL KAZMI -

<Election Title>

City of Birmingham STATEMENT OF PERSONS NOMINATED The following persons have been nominated for the election of TWO Councillors on Thursday, 3rd May 2018 for the Acocks Green Ward. PERSONS NOMINATED 4. 1. 2. 3. REASONS FOR SURNAME HOME ADDRESS IN FULL DESCRIPTION (if any) WHICH THE OTHER NAMES IN FULL RETURNING OFFICER HAS DECLARED A NOMINATION INVALID Ali 21 Flint Green Road, Conservative Party Candidate Wajad Acocks Green, Birmingham B27 6QA Baker 37 Douglas Road, Green Party Amanda Caroline Birmingham B27 6HH Flynn Flat 2, Trade Unionist and Socialist Eamonn Kevin 39 Alexander Road, Coalition Acocks Green, Birmingham B27 6ER Harmer 83 Hazelwood Road, Liberal Democrat Roger Kingdon Acocks Green, Birmingham B27 7XW O'Shea 39 Douglas Road, Labour Party John Acocks Green B27 6HH Wagg 79 Marie Drive, Liberal Democrat Penny Birmingham B27 7NY Watson 1 Rookery Road, Conservative Party Candidate Luke Selly Oak B29 7DG Williams 147 Umberslade Road, Labour Party Fiona Selly Oak, Birmingham B29 7SG The persons above, opposite whose names no entry is made in column 4, have been and stand validly nominated. Saturday, 07 April 2018 Kate Charlton, Returning Officer Birmingham City Council Elections Office The Council House Victoria Square BIRMINGHAM B1 1BB ____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Printed and published by the Returning Officer City of Birmingham STATEMENT OF PERSONS NOMINATED The following persons have been nominated for the election of a Councillor on Thursday,